Three Questions about Sex

In 1980, Pope John Paul II said that “a man is guilty of committing 'adultery in the heart' if he looks at his own wife in a lustful manner.” The mockery that followed was predictable. One commentator gave a faux confession, stating, “I've never confessed this before to anyone, but I have concupiscence [a synonym for lust] for my wife. Not just a little, but a lot . . . What makes it worse is that she has concupiscence, too.”

This and other critics had their fun, but they missed what the Pope was trying to say. The Pope was not giving a general prohibition on sexual desire in marriage (as the remainder of his remarks make clear). He was instead warning us about a particular way of experiencing and acting on sexual desire—one which reduces persons to mere objects that can be used or exploited for our pleasure.

That sex can be wrong even when everyone consents (and even when everyone consents in marriage) is a foreign thought to many today. Since the sexual revolution of the 60’s and beyond, consent has been touted as the central and often the only moral requirement for people who wish to engage in sexual conduct. In this view, so long as everyone gives full and informed consent, there is no moral problem.

The mainstreaming of this view has not produced a culture of abundant good sex. All reports suggest that Americans are in the middle of a “sex recession”—people are having less sex than in the past, and they seem to be enjoying sex less. Though porn and hookup apps are plentiful, the availability of low-cost, low-consequence sex has failed to satisfy our sexual longings. Perhaps we were longing for something else?

Several recent books and articles, all written by women, try to articulate the problem. Christine Emba observes that the promises of the sexual revolution “always seem just over the horizon, just a little way out,” and suggests that a better sexual culture would emphasize “more connectedness, more interdependence, [and] a greater acceptance of the realities of our contingent experience. The best sexual world is perhaps a less free one.”

Louise Perry writes that many young women “technically consent” to sex that they don’t really want, but this sex leaves “them feeling terrible because they were being asked to treat as meaningless something that they felt to be meaningful.” Peggy Orenstein notes that rates of “rough sex,” specifically choking, are rising rapidly among young people, and that young women in particular suffer several “physical, cognitive and psychological impacts” due to this trend. And Mary Harrington argues that we should reclaim sex from its “current jaded, affectless role as low-consequence leisure activity or mere marketing tool.” Perhaps the most radical of these writers, Harrington argues that women should reject hormonal birth control in the interest of “rewilding sex.” The Pill has allowed women to avoid pregnancy, but it hasn’t allowed them to avoid the emotional and relational consequences of sex. Sex should be made “properly consequential again.”

Whatever one thinks of the merits of these ideas, it seems clear that now is a time for serious reflection about sex and the sexual culture that we inhabit. Here we should draw a distinction between sexual culture and sexual relationships. “Culture” is the shared beliefs and practices that create identity and meaning in a group. “Relationships,” on the other hand, are the stuff of life—the obligations we incur toward each other, the self-disclosure we share, the mutual regard we have for one another. A good sexual culture will nurture good sexual relationships. I support the Church’s teaching on the law of chastity: “Only a man and a woman who are legally and lawfully wedded as husband and wife should have sexual relations.” I believe this law is an element of a healthy and moral sexual culture that lays the groundwork for good sexual relationships. Even so, I would like to understand this law better and how we can create a culture that leads people toward healthy, fulfilling, and moral sexual relationships.

As President Holland (then-President of BYU) said in perhaps the greatest talk on LDS sexual ethics, our obedience is strengthened by knowing why we should do what God commands. In introducing his topic, he said, “I wish to speak, to the best of my ability, on why we should be [sexually] clean, on why moral discipline is such a significant matter in God’s eyes. I know that may sound presumptuous, but a philosopher once said, tell me sufficiently why a thing should be done, and I will move heaven and earth to do it.” More recently, my former teacher Robert George argued, “if we do not try to understand how moral commandments serve our integral good, we will deep down—whatever we say with our mouths—believe them to be arbitrary (and experience them as oppressive—either to ourselves, or others).

Before we can consider how to create a better sexual culture, we might first consider questions that should inform the discussion. The questions I recommend are basic, but I believe that in moments of great change or crisis, recurring to foundational principles is the only way forward.

SEX AND MEANING

The first question is the most basic of all: what is sex about (or for)? Perhaps we should start with the idea that sex is not necessarily about anything—that sex has no inherent meaning, and therefore it can mean (or not mean) anything we want. But humans seem to have a hard time treating sex as meaningless. This is true even for people who identify as secular. As Ross Douthat explains, “the recent trend [in the United States] has been toward more regulation: The sexual-assault tribunals on college campuses, the changing rules of workplace harassment, the new politesse surrounding pronouns and sexual identity.” All of these norms and regulations bear witness to the fact that sex is distinct and special. It’s hard to consistently treat sex as devoid of any meaning.

Another answer could be that the point of sex is pleasure. But the answer is too quick, because it does not tell us what kind of pleasure sex is about, or if there are any unjust or improper ways of pursuing this pleasure. If pleasure is understood as genital stimulation alone, then masturbation could be the height of sexual experience.

But the great lengths that people go to in order to have sex with other people suggest that it is not merely a localized bodily sensation that people are after. There is clearly an interpersonal dimension to sex. But what kind of interpersonal connection is sought? And further, why is sex often seen as dangerous to various kinds of connection? Employers may want to build unity and connection among their employees, but sex between coworkers is often explicitly forbidden. In California, therapists are required to give their clients a brochure entitled “Therapy Never Includes Sexual Behavior.” These prohibitions suggest that there is something special and different about sexual connection, but what is it?

Roger Scruton argues that part of sexual desire is not just desire for the other person, but desire that the other person desire us. We want the beloved to love us—we want to be affirmed and recognized as desirable. Or, as Agnes Callard puts it, sexual desire is “thoroughly reciprocal desire.” This seems to be getting at something, but it doesn’t yet specify why this particular way of desiring another is distinctive from other interpersonal relationships.

And then there are the babies. Sex can and often does produce babies. How does this matter to our understanding of the purpose of sex? The ability to create new human beings is an awesome power. Returning to President Holland’s talk, sexual relationships allow us to create “that wonder of all wonders, a genetically and spiritually unique being never seen before in the history of the world and never to be duplicated again in all the ages of eternity—a child, your child—with eyes and ears and fingers and toes and a future of unspeakable grandeur.” One does not need to be religious to see this power as miraculous—anyone who thinks that humans are bearers of special rights, responsibilities, or capacities must concede that there is something deeply significant in the power to create new life.

Creating a new human person transforms a person’s life in dramatic ways. Though the birth of each new child is a gift, having a child limits and constrains the future choices one can make. Women bear the burden of this transformation in a way that men do not, and few cultures honor and recognize the sacrifices that mothers make in choosing to bear and raise children, nor do they provide support to those who inherently make those sacrifices. How do we evaluate the various competing values and claims of justice that are at stake in creating new life? We can see how sex begins to have meaning beyond the details of our own individual lives.

Sex may very well be about all of these things and more. But until we come to some basic agreement about the meaning of sex, our judgments and evaluations about sex will seem ad-hoc and ungrounded. Thus, the first step in our reevaluation of sexual culture is to answer the unavoidable question: what is sex about?"

SEX AND INTEGRITY

The second question that I think should be addressed follows from the first: what is sexual integrity? Sexual integrity is living a life of honesty and authenticity with regards to one’s sexuality. When we have integrity, we act according to the truth—as best we understand it—about sex. I hope this question is one that just about everyone could have an interest in.

How do different people understand the value of sexual integrity? Much of the LGBTQ+ movement, for example, seems to be driven by the idea that it is a matter of personal honesty and integrity to live in accordance with one’s experienced sexual desires (and/or gender identity)—that it is wrong and self-defeating to deny one’s sexuality. On the other hand, the conservative student group Love and Fidelity Network holds a yearly conference called “Sexuality, Integrity, and the University,” premised on the idea that sexual integrity is a matter of acting on our desires in accordance with a certain vision of the good of marriage (between husband and wife). Are these views incompatible? How can integrity mean such different things to different people?

Maybe you, like me, have seen and felt tension around this question of how to act with sexual integrity. As I see it, the debate is over how much of ourselves and our lives are implicated in sex. In “Plain Sex,” philosopher Alan Goldman defines sexual desire (plainly) as “desire for contact with another person's body and for the pleasure which such contact produces.” On this account, sexual pleasure is presumptively good, and there is “no morality intrinsic to sex.” If one takes this view, to the exclusion of other meanings we might attribute to sex, then sexual integrity means acting in accordance with the desires that one happens to feel (while always remembering to honor the agency and consent of other people, one hopes).

But such a stripped-down account of sex is too barren for many of us. We know a good sexual relationship is about more. But how much more, and to what extent are we beholden to our desires? For example, some people think that sexual desire is also an important part of self-actualization and self-discovery. On this account, if you do not feel sexually fulfilled in your marriage, it can be an act of radical honesty and self-love to leave your spouse for someone else. The New York Times tells the story of a couple who fell in love while married to other people. They thought their “options were either to act on their feelings and break up their marriages or to deny their feelings and live dishonestly.” One of them asked, rhetorically, “Were we brave enough to hold hands and jump?” They jumped.

One can believe that a good sexual relationship involves self-actualization and self-discovery but be concerned about the ways that this logic can be used to justify offloading our responsibilities. Perhaps sexual integrity also means integrating our sexual desires into additional goods and goals that serve the highest parts of ourselves and society as a whole, including (for example) love, commitment, emotional connection, an orientation to children and family life, and so on. Some versions of this view are compatible with same-sex marriage, while others (such as the view espoused by the Church) also require the biological complementarity of the spouses. Outside these boundaries, sex is not honest but rather dishonest—a turning away from our identity as beings oriented towards sex in a particular kind of context.

For example, for those who believe that sex should only occur in marriage, leaving one’s spouse to find sexual fulfillment with another is inauthentic and shows a lack of integrity, for it goes against one’s true identity as a being made for life-long commitment and self-sacrificial love, as well as the specific promises that one made to one’s spouse. Only within a more holistic moral and existential framework can we experience what sex is really about.

What do you think, dear reader? Is one of these views closer to the truth about sexual integrity, or is sexual integrity something else? Could a more fulfilling experience of sexuality be facilitated by boundaries that may at times feel constricting? Can sex be experienced “plainly,” or is it always already connected to other parts of ourselves? At the very least, we can acknowledge that we receive several different cultural messages about the meaning of sexual integrity.

SEX AND DANGER

And now the final question: How is sex dangerous? Some will chortle at this question—what could be dangerous about sex? Louise Perry notes that many people in our society want to believe that “sex is nothing more than a leisure activity, invested with meaning only if the participants choose to give it meaning.” But we can only say that sex is harmless if we say it is trivial. If sex has power—and most people would agree that it does—then it can also be dangerous. What is the character of this danger?

Once we put our mind to it, we can think of lots of dangers. Some of the dangers, such as STIs and sexual assault, are readily apparent. If we think back to high school or read the tabloid headlines, we can all remember the startling lapses in judgment that some people exhibit under the influence of sexual desire. The misuse of sex in these ways can be dangerous to our health or happiness in myriad ways. I wonder, though, can we misuse sex in a way that is dangerous to our humanity?

In what follows, I’d like to say a few words about how we can fail to honor ourselves and others in sexual relationships. As Karol Wojtyla (who would later become Pope John II, our misunderstood friend from the beginning of this essay) once wrote, “It would seem that the sexual relationship presents more opportunities than most other activities for treating a person—sometimes without even realizing it—as an object of use.” Sex allows us to know another person at a deeper level, which means we can also mistreat them in more egregious ways.

But how? The basic idea is that in sex, we offer our partners something deeply intimate and personal about ourselves (see 1 Corinthians 6:15–20). It isn’t easy to articulate what we offer and receive, but this very difficulty hints that sex offers a dimension of intimacy and self-disclosure not available in other areas of life. As Dietrich von Hildebrand writes, sex “is essentially deep.” As I’ve written elsewhere, “In some mysterious way, the person seems to be more at stake in sexual relationships than in other areas of life.” It’s the self that can only be revealed through intimacy. Many of us know this, though we can’t exactly say how. The more we reveal ourselves through sex, the more we make ourselves vulnerable. Could this vulnerability be a danger of sex?

By definition, vulnerability lies outside our comfort zone. Vulnerability creates new avenues for connection but can also leave us emotionally wounded, even devastated. Of course, one way of responding to this vulnerability is to deny it—to pretend that sex is not really a big deal, that we are not affected or influenced by it. This is a common move in our current sexual culture. Women generally face greater costs and challenges when the culture encourages the myth of meaningless sex. But if sex is significant, then turning away from that significance is wrong, both for ourselves and for others.

It is wrong for ourselves because we shortchange our own capacity for deep connection and self-knowledge, a knowledge that can only come to light in the presence of a beloved other (and perhaps not in a single moment but only across a lifetime of love, integrity, and sacrifice). And it is wrong for others because we deny them the gift of ourselves; we turn away from the unique disclosure we are capable of offering and instead relate only in fragments, making a show of connection while never mustering the courage to truly be vulnerable and present with the other.

To use the famous language of Martin Buber, we can have an “I-It” or an “I-Thou” relationship to others in sex. An “I-It” approach means we turn away from the deep personal disclosure and connection that is possible in sex and instead use the other as a mere means to satisfy our desires. In contrast, an “I-Thou” approach to sex means we take the full measure of what is (or can be) offered and received in sexual relationships.

And what is that full measure? That’s something I’d like to understand better. I believe we live in a time of deep uncertainty and confusion about sex, but as the German poet Friedrich Holderlin wrote, “Where the danger is, there grows the saving power.” Perhaps our culture’s ambivalence and contradictions will allow us to think more reflectively about sex. And perhaps, as we think through these questions together, we’ll come to a better understanding of who we truly are and what we are made for.

Daniel Frost is the director of public scholarship in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University. He also serves as editor-in-chief of Public Square Magazine.

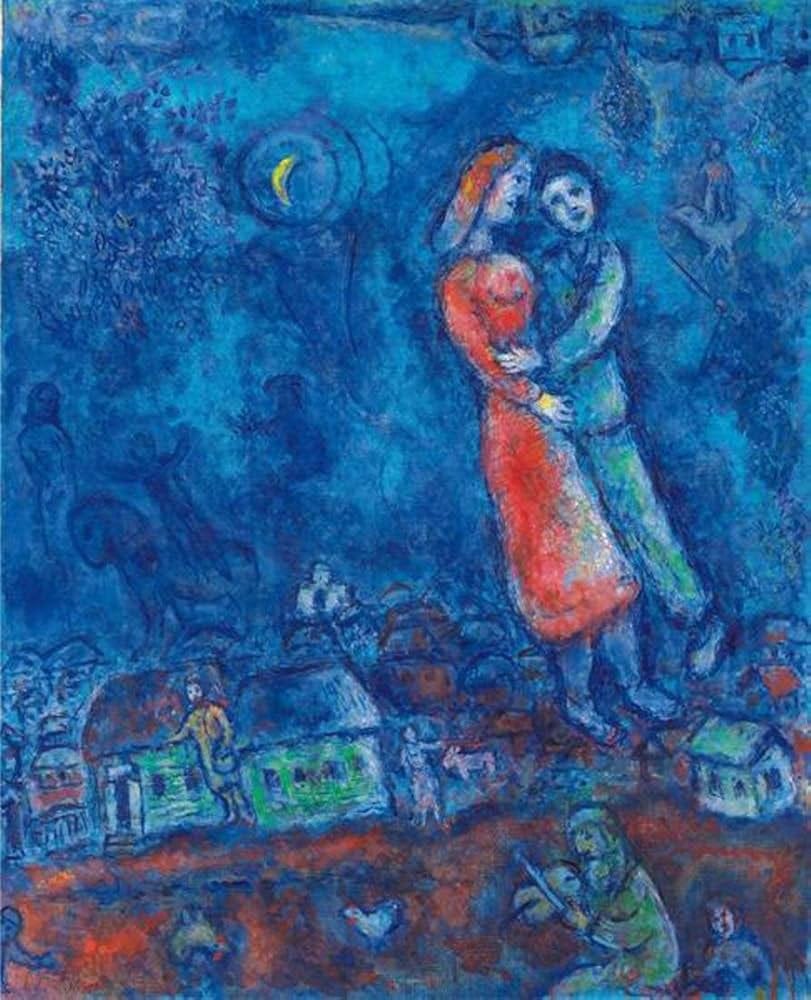

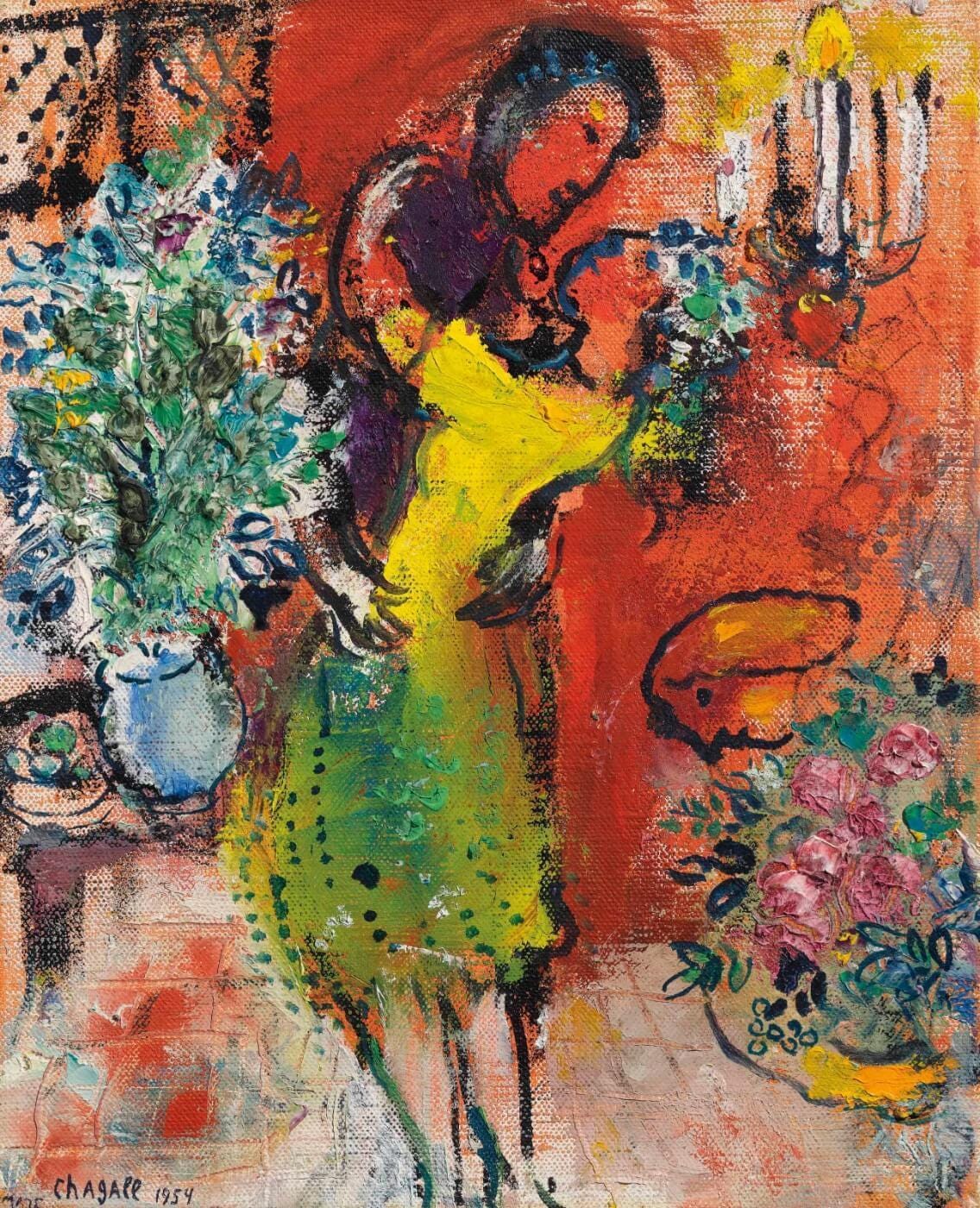

Art by Marc Chagall.

Keep Reading

The End of Love

The Feminine Divine has a storied history in religious texts and literature alike. Often, however, the face of the feminine divine shines through an earthly personage. In Goethe’s masterpiece Faust, the hero loses his duel with the devil. His contract with Mephistopheles requires the forfeiture of his soul, and in the drama’s closing scene, raucous devi…

The Fourth Nephite

The pain gripped Kelilah, hollow pangs, jagged and fierce, stabbing at her empty stomach. Is this what it had felt like, all those years ago? To spend the day fasting, using her hunger to turn her heart to God? Or in the days of darkness, waiting until light and the Savior arrived? Once, the memories had felt vivid, but over the centuries they had soften…

A thoughtful essay. I will quibble that there is an "othering" of the desires of our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters here. Being gay or lesbian is really not primarily about sex, just as being in a straight marriage is mostly not about sex. The deep human need for companionate love goes well beyond our sexual desires! Otherwise, I found the questions proposed here to be a really useful exercise!

A really good summary of the possible ethics out there. Well done!