Then Shall They Fast

Years ago, a loved one died, and I was led to wonder if it might have been my fault.

I had unintentionally left my phone on silent for several hours, and discovered that during this time it had amassed an atypical number of missed calls. The first voicemail gave the reason for the urgent volume: a family member had suffered a sudden and severe medical emergency, and I was being desperately contacted in hope that my prayer could be added to those already pleading for divine healing. In what was hours for those experiencing the crisis, but a matter of seconds for me, I reached the last message; the urgency in the voice of the caller had been replaced with resignation and devastation. It was too late. The person had died.

Would it have made a difference if I had been able to join the prayer vigil, and add my voice to the tally of concerned believers in Christ pleading for that life to be saved?

If I truly believed that “the prayer of the righteous is powerful and effective” (James 5:16, ESV), then shouldn’t I be required to acknowledge that my prayer could have tipped the scales? If I thought my inability to be present to add my petition among those of others wouldn’t have changed the outcome, would that mean I was rejecting a belief in truly efficacious prayer? Did absentmindedly leaving my phone on silent cause the intercessory tally to just not quite add up to what God needed it to be? Was it my fault he died?

I didn’t believe that then, and I don’t believe it now. But I have found myself in the position to be directly challenged about that perspective. And being able to clearly articulate the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ of the conviction of my position beyond simply an expression of feeling that it just can’t work that way has been a surprisingly elusive endeavor.

Reflecting on this experience alone wasn’t quite enough to provide me with a definitive, comprehensive solution to the complex age-old question of the relationship between human and divine agency.

But a side effect was that it did complicate my relationship with fasting. That ended up being a hidden blessing, as it was in working through the problem using this lens that I was guided toward a framework that would enable me to better articulate “the hope that is in [me]” (1 Pet. 3:15) regarding the power and utility of prayer.

I grew up in a Christian tradition where fasting was on the margins of my early religious life. But as a mature adult Latter-day Saint convert, I could no longer avoid thinking about and practicing fasting, which now entered as a regularly scheduled part of my religious routine.

The discipline of fasting forms part of the inheritance of countless spiritual traditions around the world. The value found in the practice, the reasons for it, and the meanings attached to it can be even more varied than the methods and rules by which it is accomplished.

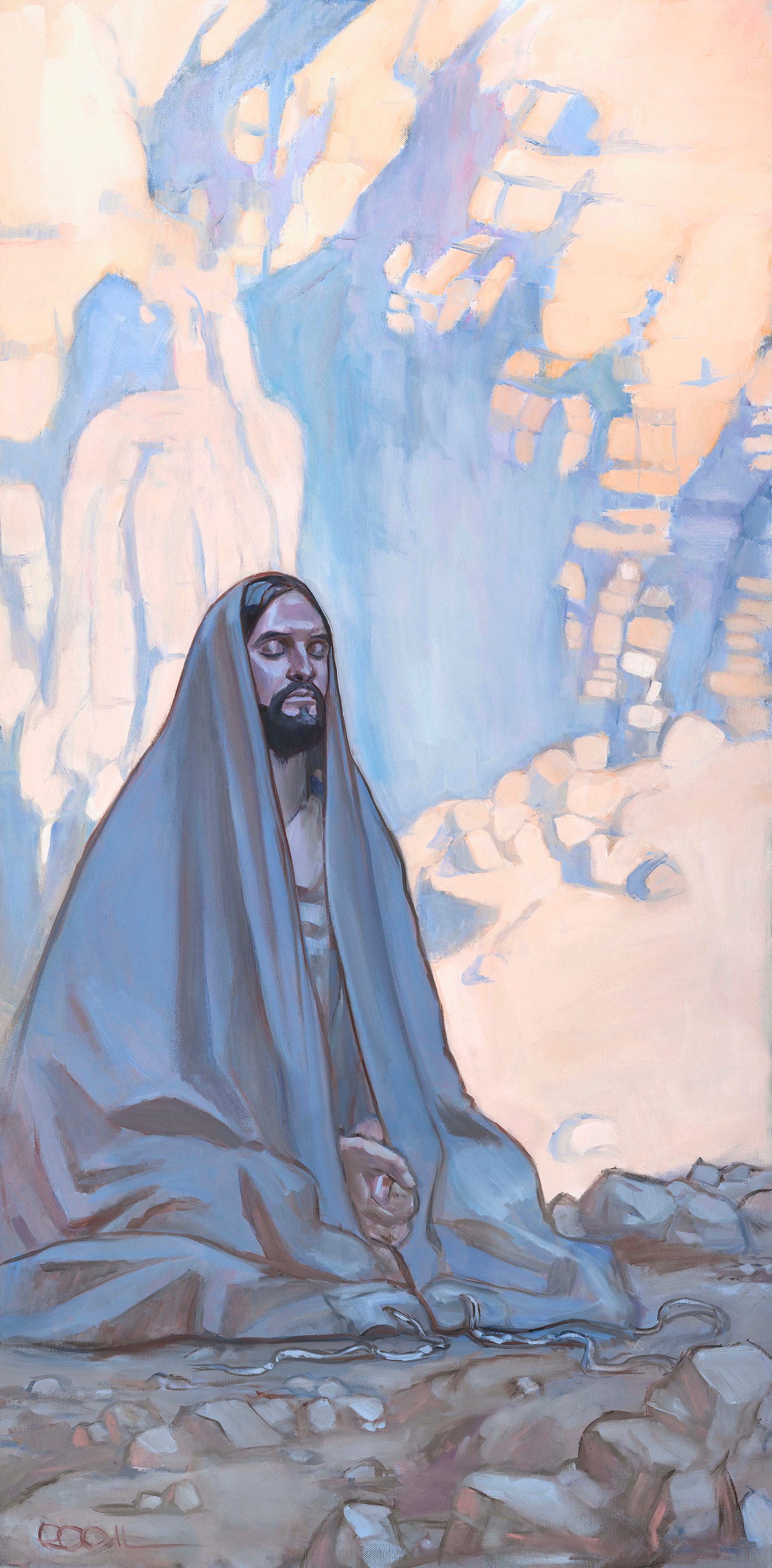

There are many aspects of the particular Latter-day Saint approach to fasting that resonated with me from the beginning of my exposure to it, and that remains true. I loved the practice of transferring the cost of meals given up into contributions to those in need. I understood how the voluntarily induced pangs of hunger could turn one’s heart empathetically to those who experienced those pains involuntarily and far more sharply. I appreciated the discipline of consciously denying one’s physical needs to focus on the nourishing of the spiritual. I saw value in the scheduled monthly observance and integration of it into our public worship cycle. All of those things made sense, and were effective devotional practices that turned my thoughts to the life of Christ, as I believe all devotional practices should. And they made scriptures such as Isaiah’s discussion about proper fasts, and the gospel accounts of Jesus’s fasting in the wilderness come alive, with immediate and personal application.

But what I never fully understood was the practice of fasting for an intended miraculous result. I had experienced enough cases in my own personal life where fasting occurred in the face of impending tragedy and ongoing painful degenerative illness, and yet as far as I could recognize, no cure or balm in Gilead arose. No miraculous change of the situation parted the waters. No transformation of hearts to accept peacefully and piously that God must have wanted or needed that loved one to suffer. In those cases, I wondered if the fasting was wasted. In the cases where others in the family or congregation joined in, did a community of people just go hungry for a few hours without benefit (with the exception of those who were fed by the suggested accompanying offering)?

What was the point? This train of thought led to additional questions. In the cases where fasting did result in a seeming miraculous outcome, could that not have occurred without the fasting? Or was the communal act indeed the key that unlocked a window in the heavens otherwise jammed shut? I knew the traditional scriptural passage where Jesus “said unto them, ‘This kind can come forth by nothing, but by prayer and fasting’” (Mark 9:29 KJV), but what did it mean? (And it was further complicated by the knowledge that the addition of ‘fasting’ to ‘prayer’ is understood by many scholars as a later addition to the text.)

Despite my questions, I’d still participate in fasts for causes, asking for the deeply desired blessing with sincere faith that God could provide, but sadly low on hope that the physical self-denying action itself was actually moving the needle in any substantial way.

Could one extra person giving up a meal make the difference between life and death? Could a missed phone call make the difference? Did questioning this make my fast a “dead work”?

With these ideas always somewhere in the margins of my thoughts, it was in the course of my regular study of the New Testament that a passage I’d read many times before, but had never thought much about, gave me pause.

In the fifth chapter of Luke, Jesus and his small crew of new disciples are being challenged for their lack of communal participation in the act of fasting—something we had just been shown Jesus personally doing on his own one chapter earlier.

“. . . They said to him, ‘John’s disciples, like the disciples of the Pharisees, frequently fast and pray, but your disciples eat and drink.’ Jesus said to them, ‘You cannot make wedding attendants fast while the bridegroom is with them, can you? The days will come when the bridegroom will be taken away from them, and then they will fast in those days’” (Luke 5:33–35 NRSV:UE).

The imagery of Christ as the Bridegroom and the Church as the Bride (and somewhat paradoxically also the wedding guests) was very familiar to me, as was the picture of the Banquet in the Kingdom of Heaven in the Age to Come. But I had never associated the scene with the practice of fasting, as was done here. There are many scriptures regularly used to promote the practice of fasting, but this one doesn’t usually come up, likely because on its surface, it’s giving a reason why Jesus and his disciples were actively not fasting.

Looking into that space, though, provided an answer for me.

When were they not fasting? When the Bridegroom/Savior was with them.

When would they fast again? When Jesus had left their presence, and they were anticipating his return, essentially a reset of the story.

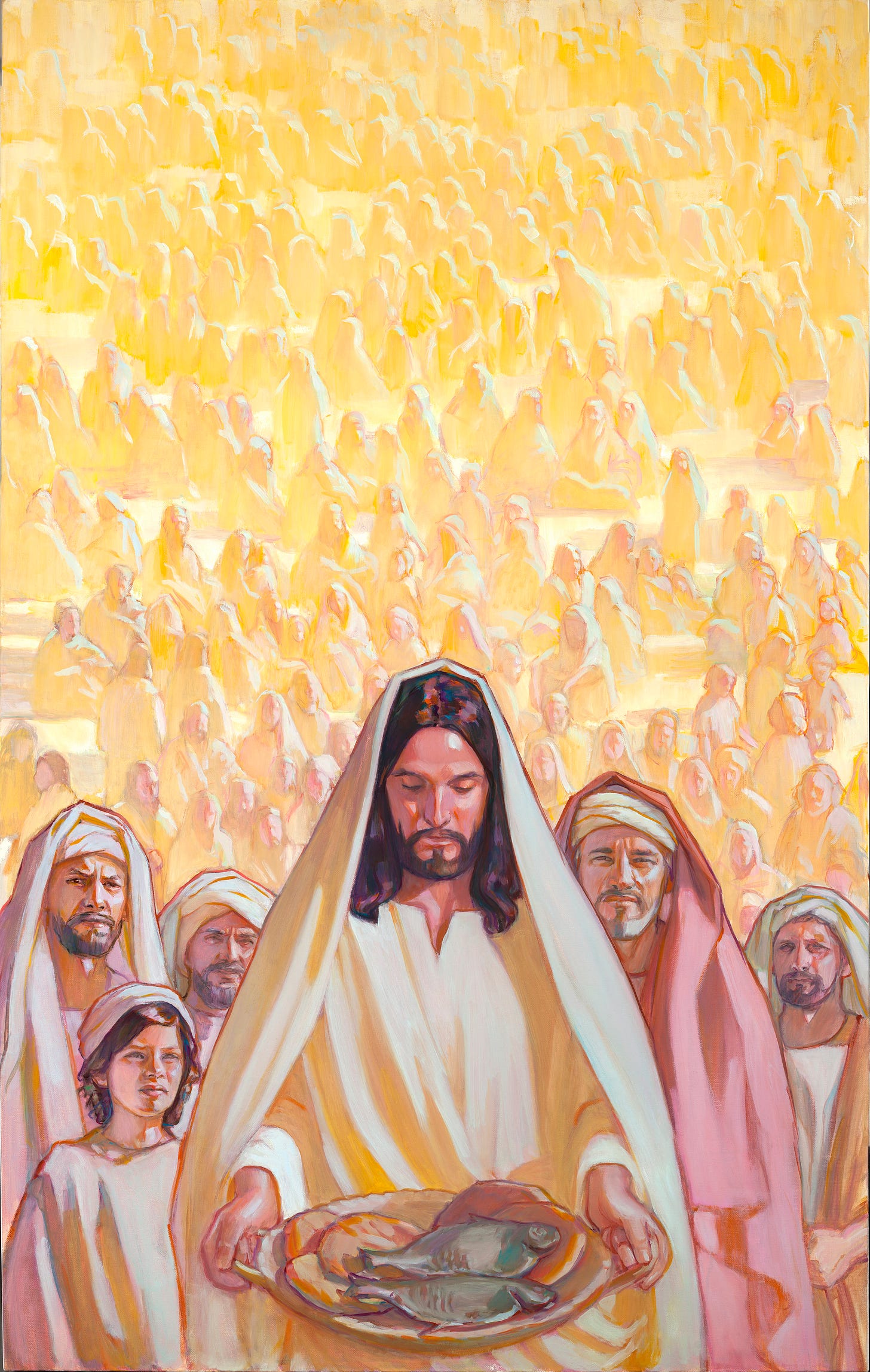

This observation changed my perspective to consider that when we’re preparing to dine with Christ in his Kingdom, a fast is actively protecting our appetites for when he arrives, when we will feast in full; that is when the fast will end, the object or intention of the fast having been accomplished. It’s been suggested that when Christ fed the multitudes with the miraculous loaves and fishes, he was giving them a sample of that eschatological banquet. He was giving them their “daily bread” in a preview of the ultimate Messianic Meal.1

Can we similarly put ourselves in this mindset when we participate in the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper? We are feasting together in memory of when Christ last feasted with his Apostles, and in anticipation of feasting once again in the presence of Christ.2

When we fast, we can recall that we’re in the period following the last supper. “Then they will fast,” Jesus said. They did, and so do we.

While the ultimate hope is centered on the coming of Christ, it is tied up in everything the arrival of the Kingdom of God in its fullness would signal. The passage from Isaiah Jesus read in the synagogue in Chapter 4 of Luke is what Jesus’s disciples were actively experiencing then, and what we are tempering our appetite for as we fast:

Good news to the poor. Release to the captives. Recovery of sight to the blind. The setting free of those who are oppressed. The proclamation of the year of the Lord’s favor.

What if that’s the ultimate object of our fast? As we regularly ask for those morsels of daily bread, through fasting we are acknowledging with our full body that the full banquet hasn’t arrived yet, and won’t until we are again with Christ. And when we have short-term fulfillments of those objectives in place, we may be seeking them out of a desire and wish to have a very specific portion of that ‘daily bread’ today, but with an expression of hope that the full meal will come regardless. We aren’t demanding an early snack in place of the banquet, but we certainly won’t reject it if by the grace of God it is given.

It’s common practice to end a Latter-day Saint fast with a prayer, where the object of the fast is again considered and requested. What comes next is often a full Sunday dinner. Sometimes it’s just a sandwich, or a handful of chips. But no matter the food, it tastes great. It fills the hunger. Sometimes you go a little too fast and overindulge. But you feast.

When I fast, I still want the ‘now’ answer to my prayer. I want the cancer cured. I want the infertility to be resolved. I want chronic pain removed. I want death to be staved off, and those who have died to return to be with me.

And if any of those things happen today or tomorrow, I will give thanks for that grace, and confess the hand of the Lord.

But if not, I no longer have any reason to consider my fast a dead work. I see it now as a powerful physical way to manifest the dual Christian imperatives to mourn with those who mourn (Mosiah 18:9), and express steadfast assurance that the blessed hope is coming (Heb. 6:18–19). I’m making myself vulnerable, voluntarily walking into the wilderness (Matt. 4:1–2), hungry, waiting for the blessings of the fulness of Christ’s Kingdom to arrive in my life in whatever way they come.

I’m expressing hope that in due time, after a period of frustration and pain, after we “cry for help . . . he will say, ‘Here I am’” (Isaiah 58:9 NRSV:UE), and we will all feast together as complete, joyful persons in the presence of the Bridegroom. I can experience the peace of renewed hope now, even as I mourn.3 Indeed, though it was obscured from me for so long, I now see clearly this passage from the Doctrine and Covenants: “Verily, this is fasting and prayer, or in other words, rejoicing and prayer” (D&C 59:14).

David L. Tayman III, a small business owner in North Georgia, blogs and tweets as “Improvement Era” on Latter-day Saint history, culture, scripture, and liturgy.

Art by Rose Datoc Dall.

Consider that it is directly following the introduction of the Lord’s Prayer with this petition for “daily bread” that Jesus gives instructions about “when ye fast” (Matt. 6:16–18; 3 Ne. 13:16–18).

For example: “Jesus’ symbolic praxis of feasting with his followers, and of weaving stories around this practice . . . [is] regularly, and rightly, seen as a symbolic evocation of the coming messianic banquet. . . . Jesus’ feastings, and the stories he told which reflect this practice, are to be read in this context, as are, perhaps, the accounts of extraordinary feedings of large crowds.” N. T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Fortress Press, 1996), 532.

As Jesus wept with his friends who were mourning Lazarus’s death even in the moments before restoring him to them. See John 11:35.

KEEP READING

Mormonism and Mammon

What should we do about money? In particular, what should we do when some people have a lot and others have a little? Wealth, and more generally our means of procuring and disposing of our material possessions, has been inextricably bound up with our desire to live a godly life since the time Adam was commanded to sacrifice the first of his flock. The C…

Invisible Realities

In Good Faith host Steven Kapp Perry sat down with Elaine Pagels, an American historian of religion and the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University. Pagels has conducted extensive research into early Christianity and Gnosticism, including the Dead Sea Scrolls. She is the author of The Gnostic Gospels, Beyond Belief, and Reve…

Shining Light in Gaza

This essay is part of our Lent series posted under our Holy Days section. During Lent, we recognize our own inadequacies and our need for a Savior. We consider how our own acts of reconciliation with others can prepare us to be reconciled with God through Jesus on the cross. To receive more essays like this during the Easter season, please

Time

Adapted from Time, by Philip L. Barlow, in the Themes in the Doctrine and Covenants series, available for purchase at Amazon and Deseret Book.

BOOK CLUB

Original Wound

A vision of healthy femininity and healthy masculinity is fundamental to our journeys back home. Satan, the Destroyer, dominates in the world by corrupting humanity’s relationship to feminine and masculine principles. He has led the charge to distort what those authentic ways truly are. His counternarrative, one based on discord, is woven throughout the…

So grateful I read this just before this coming Fast Sunday— beautifully done and lots to ponder. Thank you!