The World from God's Point of View

A Conversation with Howard Wettstein

Steven Kapp Perry, host of the In Good Faith podcast, talks with believers of all walks of faith. This podcast aims to highlight the personal experiences of believers, collecting stories of hope and inspiration. In 2023, the In Good Faith team spoke with Dr. Howard Wettstein, currently a Professor of Philosophy at UC Riverside, where his primary research areas include the philosophy of language and the philosophy of religion.

Howie: I spent twenty-five years teaching philosophy without a religious orientation. And, at a certain point, I had a religious turning in my life, but it was a lot by way of philosophy. They came together in ways that, since then, they've never been separate.

Steve: You said in an earlier publication, if we actually could explain [every emotion] in words, maybe we would never have that feeling of awe.

Howie: It's not as if, if you learn more about God, you'd feel less awe-struck. The more Einstein learned about the world, the more he felt awestruck by the world. The whole idea of knowledge is misplaced.

When God is about to destroy Sodom and Gomorrah, he says, “I can't do this without telling my loyal servant, Abraham, who has known me.” And the word ‘known’ is really interesting in Hebrew, as when you speak about Adam knowing his wife. ‘Knowing’ is not always sexual, of course, but it is always intimate.

So, Abraham is His intimate, and He feels compelled to convey what's going to happen—it's not knowledge, it's intimacy.

Steve: It seems easy in something that might be repeated monthly, yearly, weekly, or every day, to become mundane, and actually less meaningful. So, what is it about practice that you can do to maintain or create that sense of awe, or of emotional or spiritual union or satisfaction?

Howie: Repetition is a lost virtue. So, when we say Mourner's Kaddish, the practice is to say it when you've lost a loved one. In certain services, it’s said two or three times—and somehow the repetition is powerful.

Maybe I can explain why it's powerful by an interpretation that I learned about Mourner's Kaddish when my mother died. It's a strange prayer because it's a ‘glorification of God’ prayer, but it's said on the occasion of mourning. And how do those two go together, right? It doesn't say a word about the death of the loved one.

Someone said, think of it as comforting God for his loss. That was very powerful for me. When I lost a loved one, and I felt like there's a tear in the universe, to be able to comfort God for His loss is very powerful. And the fact that it's repeated three times in fifteen minutes is somehow even sweeter. It's like kissing a loved one several times.

I mean, the world is absolutely exquisite, but it's also horrible. And how do you deal with the horrible part, exactly?

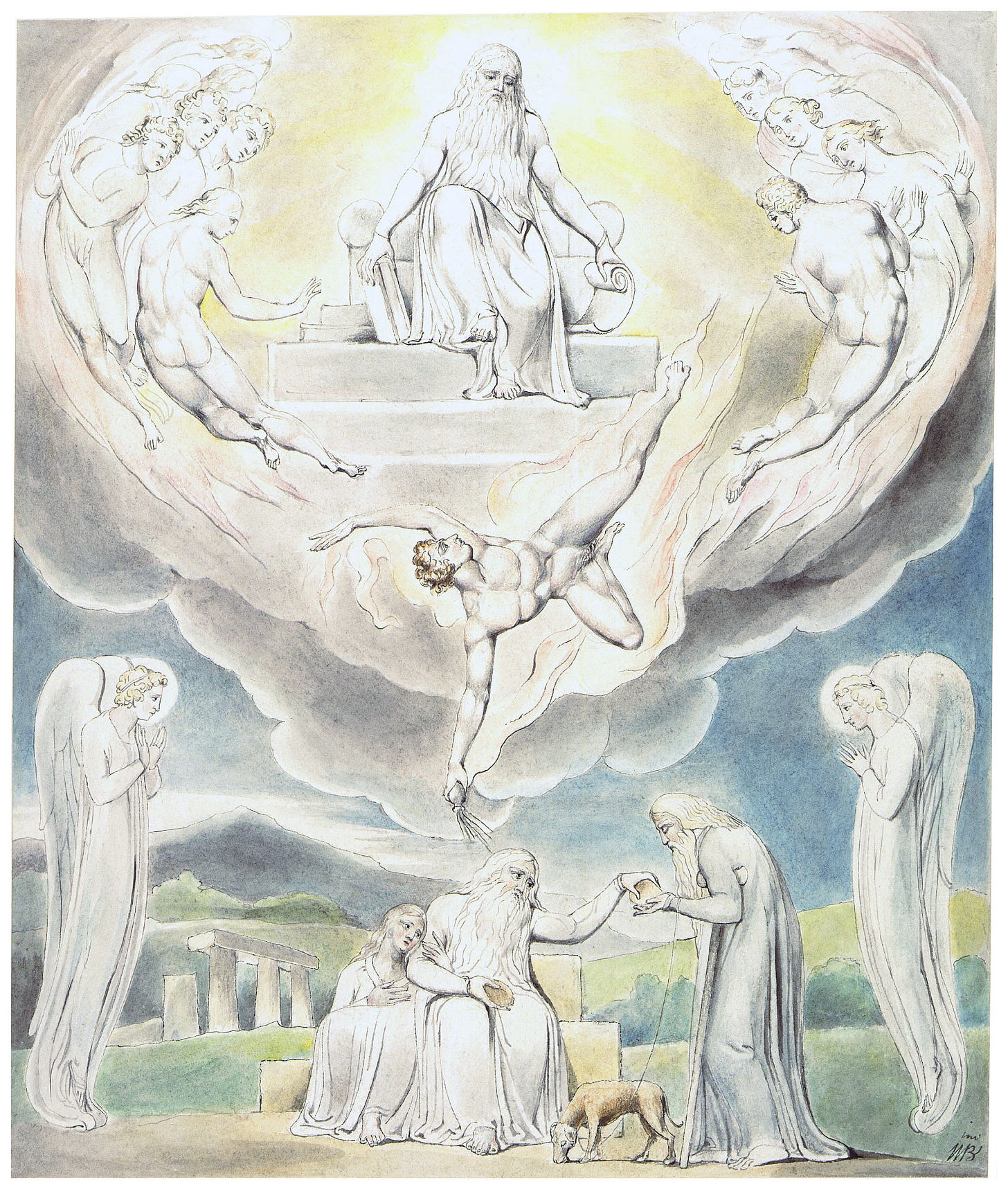

Job seems the book of the Bible that takes this quite seriously. I've spent a lot of time thinking about Job. It's just an amazing, amazing work.

The core of the story is about this guy who's lost everything. At a certain point when Job hits bottom, he's alone in the world. His friends aren't even with him, his wife isn't with him, his children are gone, and he's sitting on a pile of ashes scratching his diseased skin with a piece of pottery. God shows up, which is really amazing.

And he expresses awe, and love, and he talks about it being exquisite and awful all at once. By the end, Job is overwhelmed because, as awful as his life is at that moment, he looks at this opportunity he had to see the world from God's point of view. And it reminds me of a sort of Spinoza-talk about seeing the world under the aspect of eternity. And he's moved and astounded.

And the sentence that is sometimes translated as repenting seems to me means something else. It's something like, “I'm comforted.” The big message for me is something like God's world is astounding—awful, and exquisite, and astounding.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length. Listen to the full interview here.

Steven Kapp Perry is the host of the "In Good Faith" podcast, produced by BYUradio.org

Artwork by William Blake.