The Womb of Suffering

A Gracious Reorientation of Pain

I should not love my suffering because it is useful. I should love it because it is. . . . We should seek neither to escape suffering nor to suffer less, but to remain untainted by suffering. —Simone Weil

I recently discovered French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil and wish I could console my thirty-six-year-old, tainted-feeling self with her wisdom. Back then, my life felt like one of my dreams where I was running through a dark, earthen tunnel that emptied into a dead-end cavern. Stuck and dread-mired, I couldn’t access any gratitude or praise—the gateway of my religious conditioning into divine Presence. I couldn’t even muster a cry for help as a sense of death loomed over me.

Though I was a fervent woman of faith, this nightmare scene psychologically reflected the strange place I found myself after soul-suffering more than 80 cycles of infertility interspersed with miscarriages. My womb became a tomb, and I felt forsaken. The poetry of Lamentations 3 expressed my suffering, and I was tormented by the fear that this was somehow my own doing.

My years-long dark night of the soul was permeated with anxiety that God caused or allowed suffering because I deserved it. Per the evangelical theology of my upbringing, sin separates everyone from God and punitive wrath naturally follows as part of divine justice—part of God’s nature. Though I believed in the atonement of Jesus Christ, I was also taught that I could grieve God’s Spirit with my imperfect choices or lack of faith—causing the Spirit to depart. This implied that I could separate myself from God again (and again) and that I deserved suffering, whether caused or consented to by my just Creator. For me, this belief intensified inner fragmentation. I couldn’t reconcile my seemingly pure-heart desire to bear Life with the repeating death of hope or the literal death that my body carried and processed multiple times. My heart began to feel like catacombs.

Yet, as Weil articulated,

It is in affliction itself that the splendor of God’s mercy shines, from its very depths, in the heart of its inconsolable bitterness. . . .

If still persevering in our love, we fall to the point where the soul cannot keep back the cry “My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” . . . [and] we remain at this point without ceasing to love, we end by touching something that is not affliction, not joy, something that is the central essence, necessary and pure, something not of the senses, common to joy and sorrow: the very love of God.

In God’s mercy, the affliction of my third miscarriage became the means of a gracious reorientation around suffering. During my wholehearted grief over the loss of yet another baby, I began to sense a deeper reality. Namely, that suffering is not a punishment for my sin, but rather connects me to my Savior Jesus Christ who suffered . . . and still co-suffers with me. I started to know that the essence of Love is to redeem suffering in the midst of sin, of broken and unredeemed places. The very experience of suffering itself can awaken us to desperate hunger and thirst for Love’s redemptive presence in all places, people, and relationships—in ourselves, first. This unique communion with Jesus who suffered and still co-suffers in solidarity with us may be part of why He endured the cross, and it is integral to fulfilling God’s love.

And so my own womb resonated with Jesus’ long-suffering intercession for Christ’s body of believers on earth, reverberating with his hope for their life-giving fruitfulness. I lamented when humanity, a womb of creation, had used agency and creativity to grasp power at others’ expense instead of birthing healing through divine-image-bearing, maturing love. My heart was spiritually transfigured by Christ’s incarnation, atoning death, and womb-like resurrection, all of which together redeem death in the spirit and the flesh—to continually make love complete.

Weil observed, “Even if our efforts of attention seem for years to be producing no result, one day a light that is in exact proportion to them will flood the soul.”

The dream of my thirties didn’t end in the cavernous tomb. Unexpectedly and impossibly, something like a wrecking ball burst through the mountain-thick wall from the outside, and blinding light poured in. A shadowed outline of Jesus was before me—I ran toward Him, out of my death-trap and into renewing freedom.

The dream’s scene immediately shifted, and I was meandering with Jesus on an ancient cobblestone street lined with low door-framed rooms. Jesus beckoned for me to peek through the threshold of one, and I noticed hearth embers warming something deliciously nourishing. We walked further, past many thresholds—some softly illuminated and some cold gray—windows of my heart.

The scene transposed again, to an aerial view of what looked like a prehistoric Petoskey stone (native to my birthplace, Michigan). Some of its many greige, six-sided corallites glowed bright, others were dimly lit, and some remained dark. Jesus was illuminating my heart as it underwent the process of His redemption and restoration. My heart would alchemize to eventually resemble honeycomb calcite (native to my current home, Utah), with all its interconnected hexagonal-shaped cells radiant with an amber hue. As I became curious about the pain in my suffering, energy surged—and I could seek and receive Jesus’s co-suffering love to redeem my despair into hope, into resurrected life.

Revisiting Simone Weil’s wisdom: “I should not love my suffering because it is useful. I should love it because it is. . . . We should seek neither to escape suffering nor to suffer less, but to remain untainted by suffering.”

As I round out my forties, by Jesus’s gracious redemption, I have become and remain untainted by suffering! My eldest and two significantly younger sons are constant, physical testimonies of miraculous new life after death’s despair. And the courage I feel to prevail over fear of suffering and to step in faith as a peacebuilder testifies to the resurrection of my soul, in solidarity with Jesus, my living water and Light-source.

Ironically, the same Bible passage that previously discouraged me so deeply during the real life suffering of my thirties now comforts me. The Hebrew etymology of the middle of Lamentations 3 is fascinating. It identifies God’s chesed or steadfast lovingkindness as the sole reason we are not consumed; and it insists that God’s racham never fails. Frequently interpreted as “compassion” or “mercy,” racham also translates as “womb.” Profoundly, God’s unfailing and merciful womb of lovingkindness sustains us and does not “willingly bring affliction of grief to anyone.” Amen.

As with many things, I’m curious how my individual redemption and restoration weave with the whole, interconnected body of Christ, or—as my Latter-day Saint friends believe—with the whole human family knitting together through Christ’s atonement. My “Petoskey-stone heart” continues to awaken through suffering, to be curious about Light and honey-sweet goodness that is transcendent of afore-perceived boundaries of religions and countries, generations and time. I’m captivated by Christ’s incarnational co-suffering mercy as a rebirthing womb for all humans to grow as extensions of death-and-dread-defying, radically forgiving Love.

Perhaps redemptive co-suffering, a miraculous gift of Presence, is how healing reconciliation will birth. This is my longing as saints and sinners alike face agonizing loneliness or isolating indifference, the distress of disease and affliction, and human injustice ranging from genocide to structural violence and various forms of “othering.” This is my hope as I think about lingering effects of intergenerational violence and trauma that I observed during a recent peace pilgrimage in Northern Ireland, as I reread Patrick Mason’s witness of Rwanda, as I read news of brutality in our world, or as I perceive any hostility embedded in myself and in the religious and political cultures I engage in daily.

I’ve begun to (increasingly) recognize suffering as a womb for Christ. I pay attention to it, as a gracious portal to new life from death, to beauty from ashes, to pain-woven connectedness through shared wounds, and to a sudden flooding of the soul by light. Untainted, I watch for divine Presence, and touch the very love of God.

Lenée Fuelling is a Writer and Managing Editor for Multiply Goodness. Over the past several years, she has envisioned and helped facilitate women's interfaith events that create safe space for connection with the Divine and each other.

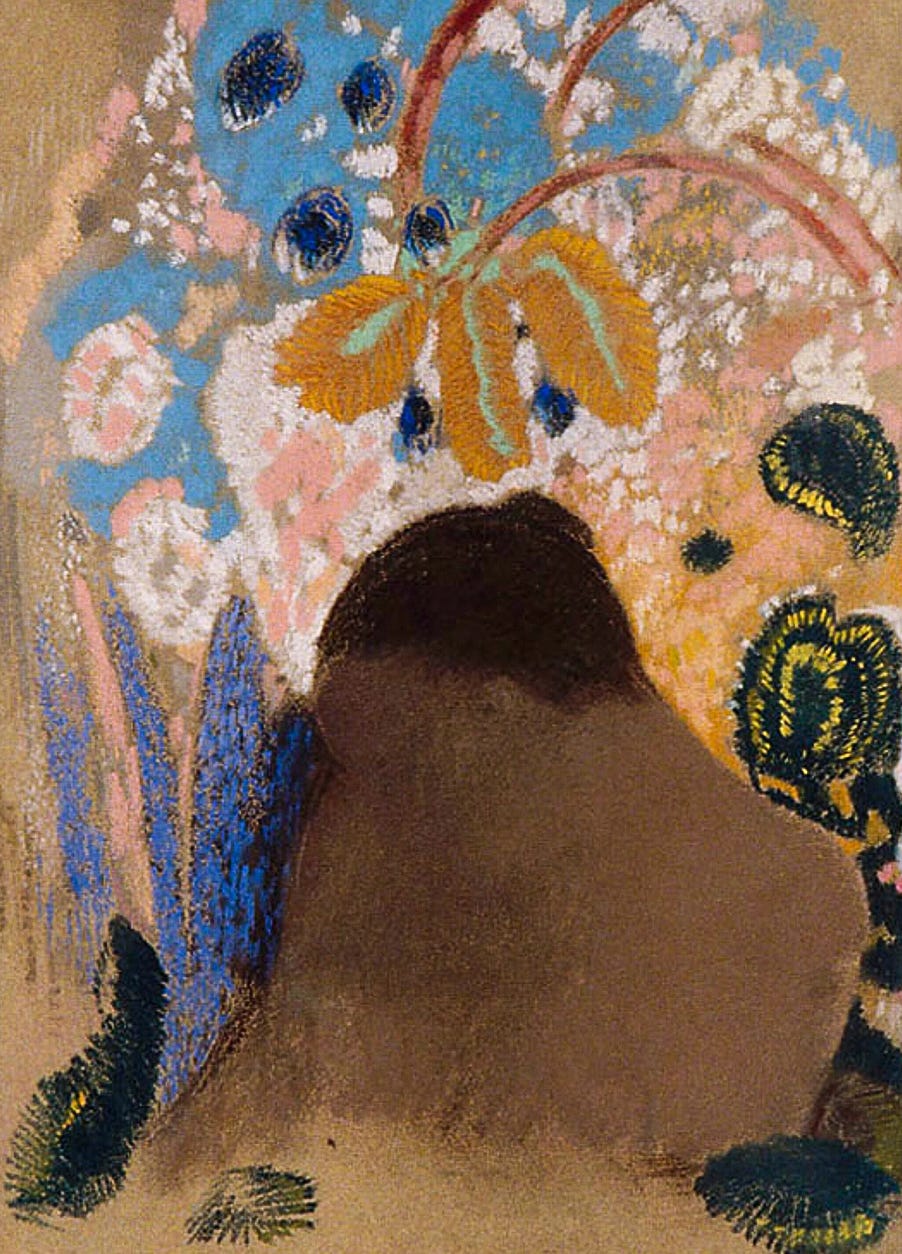

Art by Odilon Redon.

This is a lovely essay, Lenée. Thank you for sharing.