Weeks after Clever Gretele was called as Primary President, her sixteen-year-old daughter Chava was still begging to come. In the first breath after the benediction, it would begin. “Please,” she said one Sunday. “I can make myself useful. I’ll sing the songs. I’ll show them a game. I can even teach a lesson. I know lots of lessons.”

Gretele was not sure what would happen if she were to say yes, but she had no illusions that it would end well. Chava hadn’t consistently made it through primary when she was in primary. She used to get bored and escape and Heshel had to chase her down and try not to get lost on his way back. Other times, she had stayed put in her class until someone came to pull Heshel out of Sunday School, or Elders Quorum, or—on his more absent-minded weeks—Relief Society. From the time she was young, Chava could break the hardest of teachers and leave them begging for outside aid. She wasn’t a bad child, if such a thing even existed. To Latter-day Saints, God said children were pure. And when Chava was a child, it felt so true. That girl was so purely devoted to whatever emotion she felt, whatever idea she got into her head. To be fair, most children are obsessive and a little feral. But the last thing her sister Milka, or Bruno Levy, or—heaven help us all, Shmuel Peretz—needed was Chava egging them on.

“No,” Gretele said. “You are a young woman now and you have a class of your own. That’s where your loyalty should lie.” She pointed in that classroom’s direction. “Now go.”

“Of course I’m loyal to the young women,” Chava said. “But they want to come to Primary, too! Bluma and Bina are learning to play the piano. They could use some extra practice. Zusa’s here: she’s never been to Primary before. The least you could do is give her one week. And Golda wants to come work with you, she says, for old times’ sake.”

Gretele smiled. Back when Gretele’s calling had been with the young women, Golda had been the youngest of the girls. And now she was almost grown up. Those had been good times. Simpler times. And maybe Golda could help her now . . .

“No means no means no,” Gretele said. “Go to class. Tell Golda I miss her, but the Lord must need her right where he put her or else she’d already have turned eighteen.” Golda could bear her burden. And Gretele would carry her own.

Working with the young women had been easy. All they needed was a little guidance, maybe some skills. But by the time a person was twelve, they were more or less ready to take on the world. Little children weren’t like that. According to the teachings of the Church, the younger half of them were still totally innocent. And the older half were just barely learning to sin. None of them knew how to take care of themselves. That’s why God gave them such absurdly big eyes, which begged for protection. All that most young women needed was confidence and a chance to find out what they could do with it—easy enough things for a woman like Clever Gretele to produce. But children deserved love and protection and a foundation of wisdom to build on for the rest of their lives, so they didn’t have to spend so much energy for the rest of their lives making things up as they went along.

Gretele sighed. It is not an easy thing to look at a child’s giant eyes and admit that you do not know what a good, safe childhood is supposed to look like. It is not an easy thing to give children a foundation of wisdom when you have very little of your own. As the primary president, Gretele wished she knew some secret for how to keep the commandments—something besides her own system of having to try very hard all the time and then screw up all the time anyway. She wished she knew how to start right and make families so happy that no one ever got frightened by the idea of eternity. If nothing else, she wished she could teach them a game that everyone would always want to play so they would never be lonely, even when they all grew up and got hormones and smartphones—the injustice of it!—at almost exactly the same time.

Somewhere along the way, though, she’d gotten distracted and missed those secrets. All she really knew was how to make a little money here and there—but if you didn’t truly need it, according to Jesus, that was only useful for feeding pet moths. Still, if she did not herself possess any real wisdom, she could at least show them where to find it. According to the table of contents, it was hidden deep in the Primary Songbook.

Gretele gathered her things and went with Milka to the primary room. The children drifted in. She coaxed Breyndl Fischer, who was giving a talk, up to the front—next to Benny Levy, who was swinging his feet back and forth like a manic clock, and Shmuel Peretz, who was looking around like he was casing the joint. The other children sat, or lounged, or squirmed in (or near) their seats, waiting to maybe listen.

After a brief welcome by Gretele, the meeting began with Benny Levy tipping his head up toward the microphone to offer the prayer and his brother Bruno walking up beside him, to help out the Holy Ghost by whispering promptings as needed. This time, Benny had clearly prepared. Instead of repeating Bruno’s offered phrases at the same volume, he shouted them so half the building could hear.

Shmuel went next with the scripture. “We believe that all men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression,” he recited. “But not until they turn eight,” he added with a wicked grin.

After that, it was Breyndl’s turn. She gave a talk about prayer. A lot of it was mumbled, and she snuck glances out at people between lines rather than ever making eye contact as she spoke. In its own way, though, the talk was inspiring. She even told a personal story: once she had lost a pocket knife and prayed to find it. Then, one year later, she did!

And that was it. With the chore of their miniature model of a sacrament meeting out of the way, Gretele would normally turn the time over to Hannah Silber to burn through with singing. Thanks to the prophet, a primary president didn’t have to give a message or anything like that anymore. On this occasion, though, she’d arranged to say a few words anyway. “Today, we’re going to learn a very special song,” she said. “It’s about a wise man. Who knows what a wise man is?”

It was entirely possible that no one knew. But it was Primary: half of them raised their hands anyway.

Gretele looked for someone sitting extra reverently to call on first. Since most of them were swaying like grass in the wind, or bouncing up and down like they needed to pee, it wasn’t difficult. She chose Dinah Peretz.

“This week, I fell off my bike and I scraped my knee, but my mom put a band-aid on it and she kissed it,” Dinah said.

Gretele nodded. “And did that make her a wise man?” she asked. Knowing Dobra Peretz, that felt quite generous, but charity can cover a multitude of stretches.

But Dinah only tilted her head a little to the side in confusion. “My mom is a girl,” she clarified.

“That’s right,” Gretele said. It was important to let the children know they were right as often as reasonably possible. “Can anyone else tell me something about what a wise man is?”

Hands went back up. Benny Levy raised both of his. Because Breyndl Fischer had done so well with her talk, Gretele called on her next.

“A wise man is, like, a wise child—if the wise child grew up, and if the wise child was a boy, then the wise child would eventually become the wise man,” Breyndl explained.

Well? The scripture says the Lord’s truth is one great round, and Breyndl had clearly mastered that principle. “Very good,” Gretele agreed. “Any wise man, or woman, was once a wise child. So what does it mean to become a wise child?”

“Jesus!” Benny Levy shouted. Benny liked to shout “Jesus.”

“Thank you, Benny,” Gretele said. “And Bruno, thank you for raising your hand. What did you want to say?”

He immediately dropped his arm to his side. “Are there any treats today?” he asked.

“Maybe not,” Gretele admitted. “But that’s a very wise question. Now Sister Silber is going to introduce that song, and it’s going to tell us what a wise man is like.”

It took a minute for Hannah Silber, who was well on her way to producing the ward’s next future primary child, to pull herself to standing. Gretele made a mental note to talk to Bishop Levy about giving the poor woman a new calling in a room with bigger chairs. She turned the chalkboard around to reveal the words to the song:

The wise man built his house upon a rock The wise man built his rock upon a rock The rock man built his rock upon a rock and the rains came fumbling down

Ah, but what is a primary song without some actions? Hannah taught the children to tap their foreheads with a finger and the word “wise” and to make a fist and smack it against their open palm on the word “rock.” And then they all began to sing.

The children proceeded to sing “rock” quite loudly while mumbling their way through the other words. It wasn’t perfect, but it was an excellent start. “Let’s try it one more time,” Hannah said, “and then I’m going to need a volunteer.” At this, all hands immediately shot up again. “I’ll be looking for a person who uses as much energy as they can on their singing and the actions this time through.”

Gretele prepared herself to intervene as the children rose to the challenge. To show his energy, Shmuel Levy swung his fist at Bruno Levy. Bruno, however, was already climbing up on his chair to wrap his arms around his legs and cannonball to the floor. Milka simply replaced several words with the high-energy “rock,” bringing the verse to a close with a resounding “and the rocks came rocking down.” Others jumped, twisted, shouted, spun in slow circles, or lay on the floor flopping like fish. Gretele was struck once again by the beautiful, totally unselfconscious, almost drunken way they moved their bodies.

“Very good!” Hannah Silber said. After considering a few children who had fallen to the floor as a part of their actions, she chose Bruno to come and erase a few words. It didn’t take many more rounds before they moved on to the second verse, about the foolish man. The children of Chelm had even less trouble mastering that.

“How was primary?” Chava asked after Church.

“Good,” Gretele said. “Only a little violent.”

“Can I come next week?” Chava asked.

“No,” Gretele said. “But you can help me carry some bags.”

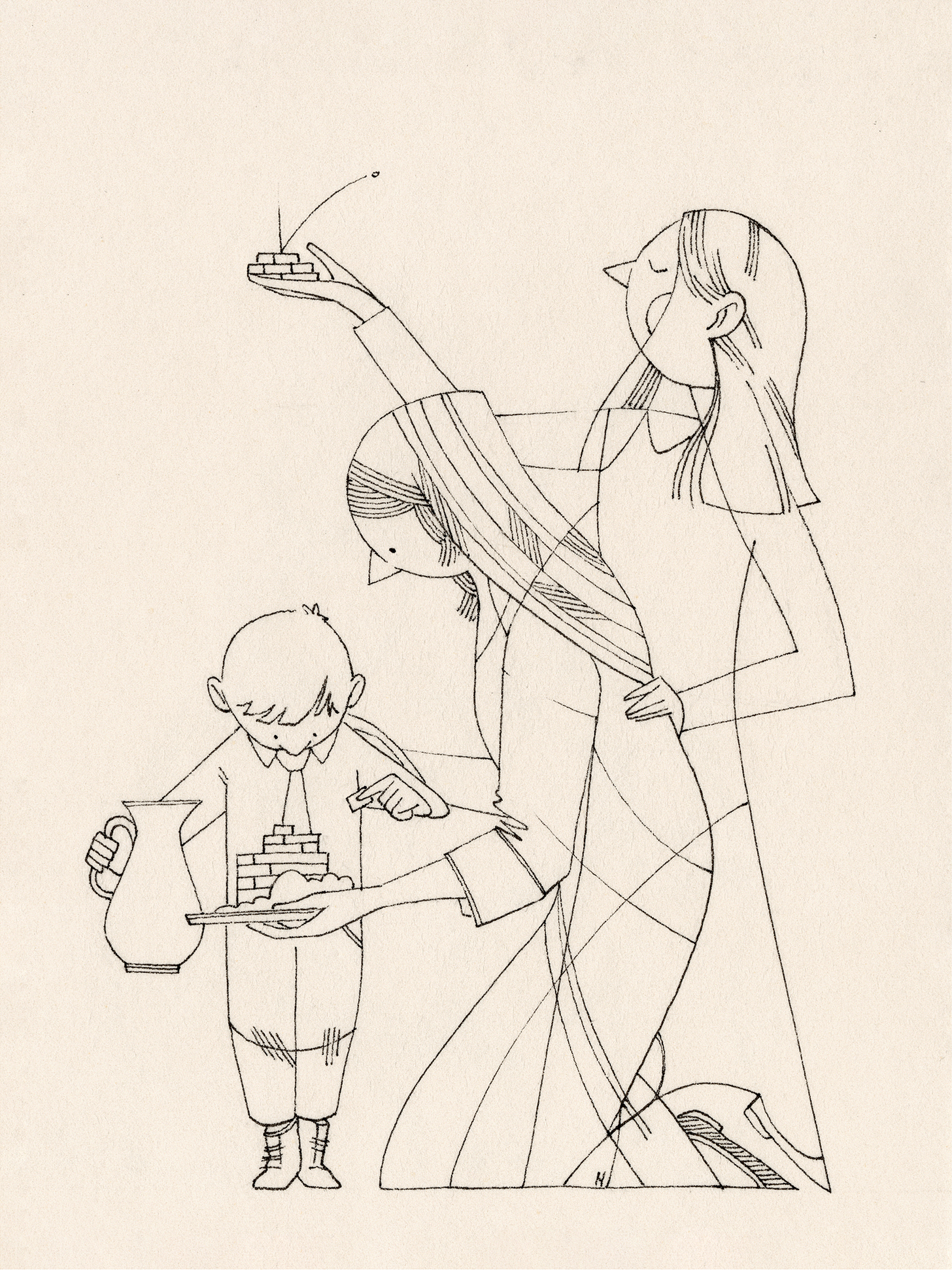

The next Sunday, Chava carried the bags full of rocks. Golda came along to carry the sand. Bluma and Bina brought armfuls of pans, while Zusa schlepped the pitchers of water. Milka carried the legos. The young women tried to linger to see what it was all about, but Gretele wasted no time in chasing them off. Jesus said to suffer the children; he never committed one way or the other about teenagers.

Just before singing time began, Gretele let the children turn around their chairs for use as tiny tables and had the supplies distributed across the classes. Except, of course, for the pitchers. “While we sing, you can build,” Gretele told them. “And if you do a good job and show respect for Sister Silber,” she promised, ”the rains can come down and the floods can come up at the end.”

With their hands busy, the voices were more subdued. But even as they built their little toy mansions, the children continued to sing:

The foolish man built his house upon the sand The foolish man built his sand upon the sand The sandman built his house upon the fool and the rains came mumbling down

Some built lanky towers. Others opted for squat, heavy fortresses that sank deep into the miniature beaches. Benny Levy just piled a few loose legos on the rock and buried others beneath the sand for future harvests.

At length, singing practice was done and the hour of judgment had arrived for all their creations. Gretele and the other adults moved from pan to pan, pouring water over plastic roofs.

The rocks were indeed impervious to water. The little houses built on them? Not so much. Benny’s loose pieces were rapidly swept away. The towers didn’t stand a chance. Even Shmuel’s solid fortress slid over to the side until its far wall was well past the edge of the foundation rock. It hung, half suspended in air for what felt like a long while, and then tipped over and crashed down on its side. Gretele stared at where it lay, firm but displaced. Gone astray like one of those Bible sheep.

The houses in the sand did much better. Benny’s hidden pieces stayed hidden. A few of the towers fell, but most leaned. Shmuel’s fortress stayed right where it was, no matter how much water they poured over and across it—though when the pan got really full, the sand floor inside was visibly damp.

“Why did the sand ones stay up?” Breyndl Fischer asked.

“Did you bring any treats?” Bruno Levy added.

Gretele puzzled over what had happened. The song seemed so clear. But the results were clearer. Which one should she trust?

“This goes to show how much we still need revelation,” she declared at last. “God told Noah to build an ark, not Adam, because that commandment only made sense for Noah’s generation. Building a house on a rock wouldn’t have turned out so well for him either!” She looked on the side of a rock at Shmuel’s sideways fortress. “I think sometimes we need to be firm about everything so we can’t be shaken. But sometimes—maybe it’s better to have a little wiggle room when the rains come. Learn how to give a little. I don’t know.” She turned toward Hannah Silber. “Either way, it’s a very fun song.”

Hannah agreed, and taught them an extra verse, which she made up on the spot:

The wise man built his house so it would stand The wise man built it somewhere on the land The wise man built a house like God had planned and he didn’t let the rains get him down

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Artwork by David Habben.