Some of you may have four or five beautiful daughters, who all won their young women of excellence awards, were all married in the temple, and are raising perfect young families. You have several sons, handsome and strong as stripling warriors, who all reached eagle scout and served honorable missions. This Mother’s Day talk is not for you. This talk is to honor real mothers of real families.

The Bible is a family narrative. After we get through the story of creation, Genesis settles into its real focus: families. The striking fact to any reader is that all these families are dysfunctional. The very first son we are introduced to, Abel, is slain by his angry, jealous brother. Isaac has an elder brother, Ishmael, who is harshly treated and ejected from the family home. Jacob and Esau fight with each other while still in the womb, and with his mother’s help, Jacob steals the birthright from his elder brother. Then he is so afraid of retaliation, that he runs away and hides with his uncle for over twenty years. Jacob’s favorite son is Joseph. He appears in the story as the favored, pampered child, who creates so much resentment in his eleven brothers that they plot to kill him, but let him off relatively easily by instead selling him into years of slavery.

About now, some of you are probably thinking this doesn’t sound very much like a mother’s day talk. But that’s because I want to say something different today about being a mother, or a parent. Why are these stories given to us? Why show us the struggles, and disappointments of great matriarchs and patriarchs, good women and men of the past? Where are the perfect, happy families? I believe these scriptural accounts are preserved for us to give us perspective and comfort, to let us know that we are not alone in our imperfections, in our failures and in our sin.

During the filming of “The Mormons,” my wife Fiona was asked by Helen Whitney on camera: “So tell me about the perfect Mormon mother.” Fiona answered, in her typically meek and understated way, “The perfect Mormon mother is an invention of Satan. She should be hunted down, found, and shot on sight.”

Much harm is done by measuring ourselves against imagined ideals. In the year 1840, the Englishman Thomas Carlyle published an important book called, “On Heroes and Hero Worship.” We all want heroes to worship. It is a convenient and almost irresistible form of idolatry. It’s easy enough to see how Americans do this with celebrities and sports stars. But we in the church do it as well. The very same year that Carlyle wrote his book, Joseph Smith was in Washington DC, giving a public sermon. Among other things, he said this: “I have been represented as pretending to be a Savior, a worker of miracles, etc. All this is false. I make no such pretensions. I am but a man. A plain, untutored man, seeking what I should do to be saved.”

I think the Lord keeps trying to tell us this through scripture stories, but we refuse to listen. We refuse to see that salvation comes not to the perfect, but to the sinners who repent. Greatness is not the absence of weakness, it is victory over the weakness. Joy is not the absence of sorrow. It is triumph over the sorrow. If we learn anything from the scriptures, it is that pain is part of the process.

Latter-day Saints are often accused of believing in a different God than other Christians. In some cases this may be correct. We believe in the Christ of Gethsemane, and in the God of Enoch. The one of whom Enoch recorded:

And it came to pass that the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept. And Enoch said unto the Lord: How is it that thou canst weep, seeing thou art holy, and from all eternity to all eternity? The Lord said unto Enoch: Behold these thy brethren; they are the workmanship of mine own hands, and I gave unto them their knowledge, in the day I created them; and in the Garden of Eden, gave I unto man his agency; And unto thy brethren have I said, and also given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood;… and among all the workmanship of mine hands there has not been so great wickedness as among thy brethren….misery shall be their doom; and the whole heavens shall weep over them, even all the workmanship of mine hands; wherefore should not the heavens weep, seeing these shall suffer?... and until that day [that my Chosen shall return unto me] they shall be in torment; Wherefore, for this shall the heavens weep (Moses 7:33-40).

Yet that was not the first time we have record of God weeping. In Joseph Smith’s greatest vision, he saw what has come to be called the War in Heaven (Doctrine and Covenants 76:26). “This we saw also, and bear record, that an angel of God who was in authority in the presence of God, who rebelled against the Only Begotten Son whom the Father loved and who was in the bosom of the Father, was thrust down from the presence of God and the Son, And was called Perdition, for the heavens wept over him.” Perdition, of course, does not mean damnation. It means lost. Sons of perdition are the ones the Father has lost.

We do not know why one third of the hosts of heaven rejected the Father’s plan, opting instead for an alternative proffered by Lucifer, “the one who bears light.” Indications are that the opportunities offered by the plan of salvation were as tremendous as the costs required. And so the scriptures record two responses:

“The morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy,” we read in Job 38. But “his tail drew the third part of the stars of heaven, and did cast them to the earth,” we read in Revelation 12.

It seems likely that it was the suffering, the tragedy, the heartache and the inevitable wounds, that frightened one out of every three souls to the point they turned away from the Father. The scriptures, perhaps surprisingly, attest to the fact that Lucifer and his followers had good reason to be afraid. The cost of agency can be excruciating. That is why the story of the first family in the Bible is a story of pain and loss. In losing Abel, Eve and Adam were only experiencing what the Father himself had known—the pain of children who turn away from the light.

From the Father’s heavenly offspring to the present, no generation is exempt, none seems to escape the family pain and sorrow. There are no perfect families in the Bible. No fathers, and no mothers, with flawless records. What we do see are parents who persevere. Let’s look at a few examples:

In Genesis, we read that Esau married outside the covenant, “a grief of mind unto Isaac and to Rebekah” (26:35). She was also concerned for the future of her son Jacob, and the influences being exerted by neighboring tribespeople. So despondent did she become, that she said to her husband, “I am weary of my life because of the daughters of Heth” (27:46). Yet she persevered. And in the most patriarchal society ever recorded, she found a distinction unequaled by any man or woman of her time. With troubling forebodings about the two children she carried in her womb, she approached the Lord in prayer. “She went to enquire of the Lord,” the scripture records, and then it notes that the word of the Lord came unto her….” You may search the Old Testament in vain. That is the only biblical example we have record of, where the Lord deigns to speak by revelation to an individual, outside of prophetic channels. And it was to a troubled mother who persevered in faith.

Eve, the mother of the race, saw paradise transformed into exile, family feuds, death and apostasy. And yet, even after the loss of Eden, she found reason to rejoice.

“And Eve, his wife, heard all these things and was glad, saying: Were it not for our transgression we never should have had seed, and never should have known good and evil, and the joy of our redemption, and the eternal life which God giveth unto all the obedient” (Moses 5:11). Not the absence of sorrow. Joy triumphing over the sorrow.

Book of Mormon

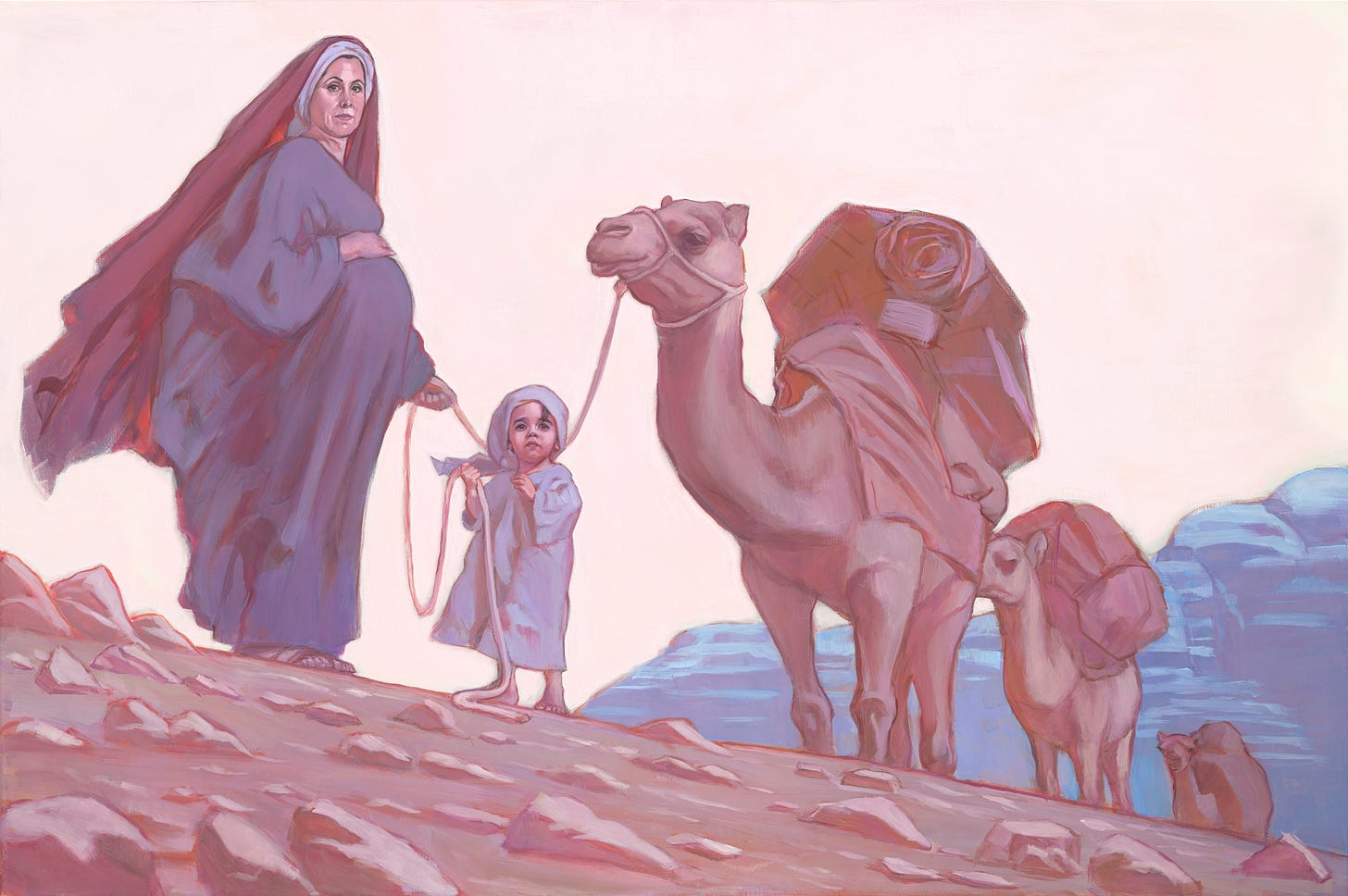

The first sentence of the Book of Mormon proper is the header, written by Nephi, in which he characterizes what is to follow as “an account of Lehi and his wife Sariah and his four sons.” The Book of Mormon, in other words, in fact and in the eyes of its first author, is the story of a family. In the text’s introductory sentence, Nephi’s first thought is to cast himself as a son of “goodly parents,” “taught in all the learning of my father,” tempered nonetheless by “many afflictions.”

Nevertheless, this starring family of the Book of Mormon does not have four perfect sons who all go on missions and marry in the temple. Sariah is a study in the rocky road of motherhood: “Sariah…truly had mourned because of us” (1 Ne. 5), Nephi records, in words that strike close to home for all of us.

The most spectacular vision described in the Book of Mormon is the vision of the Tree of Life, one that spans continents and history. It describes the birth and ministry of Christ, the discovery of America, the populating of the western hemisphere, the destruction of the Nephites. But to Lehi, it is about one thing, and one thing only. For Lehi, in his first retelling of the story, seems unable to move beyond what it meant in terms of his own family. Nephi records, “These are the words of my father: . . . And Laman and Lemuel partook not of the fruit.” And even though Lehi at this time discusses other matters pertaining to his vision (“all the words of his dream . . . were many”), Nephi only notes that “because of these things which he saw in vision, he exceedingly feared for Laman and Lemuel, yea he feared lest they should be cast off from the presence of the Lord. And he did exhort them then with all the feeling of a tender parent, that they would hearken to his words” (8:34-37).

Like the Old Testament, then, family stories dominate the subject matter of the early sections of the Book of Mormon. They pervade and eventually conclude the narrative as well. The poignant concern of Lehi for his sons is mirrored later in the paternal worry of King Mosiah for his missionary sons about to proselytize a violent and hostile people in Lamanite territory. His fears are allayed when he obtains a revelation expressly telling him, “Let them go up, for many shall believe on their words, and they shall have eternal life; and I will deliver thy sons out of the hands of the Lamanites” (Mosiah 28:7). The righteous Alma the Elder has a particularly recalcitrant son, who goes about seeking to destroy the Church his father founded. When an angel appears to Alma the Younger in an episode reminiscent of Paul on the road to Damascus, the miraculous conversion that ensues is traceable to a father’s love. “The Lord hath heard the prayers of his people,” the angel tells the stunned youth, “and also the prayers of his servant, Alma, who is thy father; for he has prayed with much faith concerning thee that thou mightest be brought to the knowledge of the truth; therefore, for this purpose have I come to convince thee of the power and authority of God, that the prayers of his servants might be answered according to their faith” (Mosiah 27:14).

Even without angelic intervention, the power of loving parents proves potent. Nephi implicitly attributes all that is good in his life to “his goodly parents,” and having been taught “in all the learning of my father” (1 Ne. 1:1). The first conversion recorded in the Book of Mormon occurs when Enos goes to the forest to hunt, and, as he writes, “the words which I had often heard my father speak concerning eternal life, and the joy of the saints, sunk deep into my heart” (Enos 1:4). The miraculous preservation of the warrior youths of Helaman is expressly attributed by them to their having “been taught by their mothers, that if they did not doubt, God would deliver them” (Alma 56:47). And the last two characters given voice in the Book of Mormon, silhouetted against a battlefield of appalling carnage, are the warrior prophets Mormon and his son Moroni, who vainly battled to save their people, by preaching and by force of arms, from a spiral into irredeemable depravity and death.

When the final scene wraps up, as when the drama began one thousand years earlier, fragile hope resides in the son who occupies a darkening stage. The family tragedy that escalated into a civilization’s utter destruction is in the end reduced, once again, to loss that is profoundly personal and relational. The abstractions of historic catastrophe collapse into a family circle. The seeds of destruction, the hope of spiritual survival, and the consequences of evil, never really move outside the local and the personal.

With his last words, Mormon laments the scene before him:

My soul was rent with anguish, because of the slain of my people, and I cried: O ye fair ones, how could ye have departed from the ways of the Lord! O ye fair ones, how could ye have rejected that Jesus, who stood with open arms to receive you! Behold, if ye had not done this, ye would not have fallen. But behold, ye are fallen, and I mourn your loss. O ye fair sons and daughters, ye fathers and mothers, ye husbands and wives, ye fair ones, how is it that ye could have fallen! (Mormon 6:16-19).

How fitting, that the same scripture that began with a family patriarch struggling to preserve his family, ends with a similar scene of grief for a family torn asunder by poor choices.

But it is to the Bible that I wish to return in my closing thoughts, and on a happier note. I wish to conclude with the story of Joseph in Egypt. There are really two stories here. The story of Joseph, and the allegory of Joseph. The first, recounting the actual events in the life of Joseph, is merely beautiful and moving. The second, relating the greater realities the story points us to, is spiritually healing and wondrously sublime.

The story goes like this. Young Joseph, beloved son of Rachel and Jacob, is aware from his youth that he has been foreordained to a leadership role, one that is bound up with the temporal salvation of his family. The Lord has told him so in dreams. In one dream, the sun, the moon, and even the stars, bowed down and worshiped him. Not the kind of dream to endear a young boy to his older brothers. His brethren seethe with a resentment that grows deeper by the day. At last they conspire to kill him, but at the last moment are persuaded by Reuben to sell him instead to a group of Ishmaelite slavers. After time as a slave and a bout in prison, he rises to high position in Pharaoh’s court, and eventually is in a position to help his family.

But this story is also an allegory. For Joseph, we know, is a type. He is a shadow and forerunner of someone else. Another individual, who was aware from his youth that he had a foreordained mission, and went intently about his father’s business. This youth also elicited hostility, opposition, and eventually the threat of death. He, too, was part of a transaction in which several pieces of silver traded hands. And he too emerges at the end as a viceroy, that is, the one who stands on the right hand of the king. Joseph was, of course, a type of Christ. So what is the allegory of Joseph’s life?

Joseph comes at the end of a long line of family heartache. The discord of pre-mortal heaven has seeped through the veil, and corrupted the earth and its inhabitants. Brother slays brother, or steals from the brother, or conspires against the brother, or sells the brother into bondage. A murdered Abel, an exiled Ishmael, a robbed Esau, guilty and remorseful brethren of Joseph, worried Rebekah, disconsolate Adam and Eve, a grieving Jacob. Then famine, encroaching disaster—the whole society is threatened with destruction, and at last, in their desperation, they turn to the viceroy, the intercessor with the king, for salvation. And this is what happens:

And the famine was over all the face of the earth…. and when Jacob saw that there was corn in Egypt, Jacob said unto his sons, Why do ye look one upon another? And he said, Behold, I have heard that there is corn in Egypt: get you down thither, and buy for us from thence; that we may live, and not die. And Joseph's ten brethren went down to buy corn in Egypt. And Joseph saw his brethren, and he knew them, … but they knew not him.

And perhaps you remember what happens next. Joseph plants the silver cup in Benjamin’s sack of grain. When it is found, he threatens to keep this youngest of the brothers as a slave in Egypt. At this point, dependent, humbled, and desperate, Judah offers his own life in exchange for Benjamin’s. In other words, he has gone from a wicked brother having murderous intent, to a kind and compassionate one, willing to offer the ultimate sacrifice for his brother. He has been healed. And this is what happens next:

Then Joseph could not refrain himself before all them that stood by him; and he cried, Cause every man to go out from me. And there stood no man with him, while Joseph made himself known unto his brethren.

And he wept aloud: [so loud, we read, that] the Egyptians and the house of Pharaoh heard. And Joseph said unto his brethren, Come near to me, I pray you. And they came near. And he said, I am Joseph your brother, whom ye sold into Egypt. Now therefore be not grieved, nor angry with yourselves, that ye sold me hither: for God did send me before you to preserve life (Genesis 45:1-5).

The point, my point anyway, is this. The scriptures are not about perfect families, or perfect mothers. They are about perfect love. And that love is found in Christ. In the allegory of Joseph, this perfect love of a Savior is the love that heals all wounds, and allows our hearts to be knit together, with our families and with our God. Across, and in spite of, the ravages of sin, of selfishness, and of our own inadequacies. The scriptures tell us that good mothers, like good fathers, are not perfect. And they will not be spared pain. But they endure, with faith in Christ and in his promises. And at the last day, our shock and surprise may be as great as that of Joseph’s brethren, who could not possibly have anticipated how wisely, and providentially, and fully, the reach of the Lord’s saving arm extended. And perhaps at that day, as in Joseph’s own, the reunion will be filled with so much weeping that it will be heard in adjacent mansions.

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

I love this. Thank you Brother Givens. This echoes a journal entry I wrote when we were studying the Old Testament a couple years ago in CFM:

Using Come Follow Me, the Old Testament has blossomed before me even more so than it had in my previous studies. One message, or principle has begun to open itself up to me: God can save us, sanctify us, purify us and work in and through us despite the dysfunction, messiness and even sinfulness of our lives. Not only that, but He is with us; He journeys with us, guides, nurtures and protects us all along our way as we strive to know Him and keep His commandments and keep our covenants. I feel the great love, mercy and comfort in His choice of what to include in His holy canon: the deeply personal lives of the family of Israel. No mistake is hidden, no embarrassment is cloaked in secrecy. The horrific sins of these chosen people are displayed for all to see- revealed to generations upon generations. Why? I believe it is in part for the tender encouragement that there is hope for us all. If God’s chosen people can still stay chosen; if they are still eligible for His blessings despite their blunderings, then so can we also be.

God knew we would face feelings of hopelessness regarding our families, our own flawed past, and our current, own brokenness. Each time I am tempted to despair in all these things, I remember the people of Israel persisting in faith despite the brokenness in their own lives. I remember Jacob with his persistent faith though dreams he endlessly worked for and gave his life for never really came to fruition in the ways he had hoped; I remember Judah and his breathtaking forgiveness of his father’s negligence to love him, his repentance from horrible sin, and his stunning self-sacrifice; I remember Joseph and his unmatched patience, faith and trust despite time and again being rewarded evil for his goodness. If willing vulnerability is a characteristic of the most pure kind of love, then the scriptures are one of the most pure and beautiful expressions of love because they are indeed so vulnerable. I feel God’s gentleness, encouragement and kindness that surpasses any other as he gives us examples of His love, forgiveness and power in these vulnerable stories. I receive them with a joyful humbleness and awe for the love He offers me through these priceless texts.

This was beautiful, thank you