The Spirit of a Sentence

Why Punctuation Matters in Our Sacred Story

Punctuation may seem small, but as anyone who has tried to understand the scriptures knows, small things often carry great meaning. A single comma can open or close the door to revelation. It can reshape the very message a sentence conveys. When punctuation is added or shifted in a sacred text, it doesn’t just tidy up grammar—it can quietly shape doctrine and influence hearts.

To make this clear, let’s take a simple example. Imagine a high school principal writing to a friend about school clubs. They might write one of the following sentences:

The drama club is the only registered and active club in the whole school with which I am well pleased.

The drama club is the only registered and active club in the whole school, with which I am well pleased.

The first sentence, without the comma, centers the principal’s delight in the drama club. There may be other clubs, but this is the one that brings them joy.

In the second sentence, however, the comma shifts the tone. Now, it sounds as if the drama club is the only club that exists—and the principal happens to be pleased with it too. The focus moves away from delight and toward exclusivity.

A single comma changed the emphasis. One version highlights approval; the other implies singularity. Both are grammatically sound. But they express something very different. That’s the power of punctuation. It can gently—or not so gently—redirect our understanding.

Now let’s consider how this principle plays out in a passage that many of us who grew up in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints know by heart. As a child and young adult, I loved this scripture. I trusted it. I believed it. And I still cherish the truths it holds. It helped me feel close to God and gave me a sense of belonging in His work. The verse I’m thinking of is from Doctrine and Covenants 1:30, which reads:

“…the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth, with which I, the Lord, am well pleased, speaking unto the church collectively and not individually.”

Many members of the Church have drawn strength from this verse. I know I did. At the same time, it’s important to remember that the weight we place on specific words can often come down to how we read them—and even to where we place our commas.

Just like in the principal’s email, the placement of that first comma matters deeply. Read it again without the comma:

“…the only true and living church upon the face of the whole earth with which I, the Lord, am well pleased…”

This slight shift in punctuation leads to a new possibility—one that emphasizes not exclusivity, but divine approval. It leaves room to interpret that there may be other churches that are also true and living, but this is the one, at that time, with which the Lord is well pleased.

So how can we know which reading is closest to the original intent?

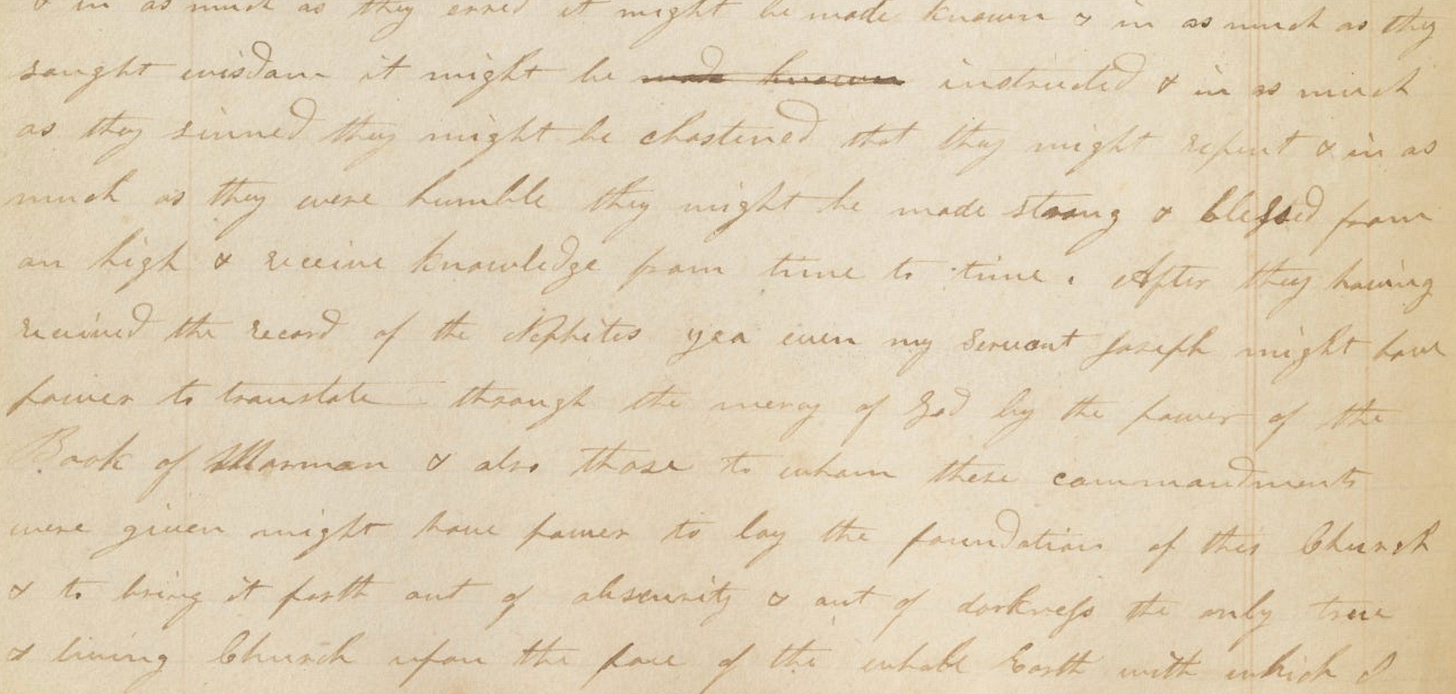

Thanks to the transparency and scholarly dedication of the Church’s own Joseph Smith Papers Project, we now have access to the earliest available manuscripts of this revelation. When we turn to the original version from November 1, 1831, something remarkable happens. That comma—the one that changes the whole sentence—isn’t there.

You can see it for yourself, directly from the Church’s own archival efforts.

The comma was added later—by an editor, not by Joseph Smith. And while punctuation wasn’t used consistently in early documents, this editorial addition still reflects a choice. It shaped the interpretation of a foundational verse. It took a message of God’s pleasure and reshaped it into a claim of total exclusivity.

Someone might argue that punctuation was informal or absent in the early 1800s, and so later insertions are just harmless corrections. But this overlooks two important truths:

First, regardless of the conventions of the time, the original phrasing of the sentence—without that comma—is what was recorded under Joseph Smith’s dictation. The comma, and the exclusivity it lends, was not revealed. It was editorially imposed.

Second, even if we bracket the issue of original manuscripts, the internal logic of the sentence points back toward the interpretation that emphasizes divine approval, not exclusivity. Let’s return to our drama club analogy:

The drama club is the only registered and active club in the whole school with which I am well pleased, speaking unto the club collectively and not individually.

The drama club is the only registered and active club in the whole school, with which I am well pleased, speaking unto the club collectively and not individually.

In the first sentence, the principal’s comment makes clear sense: they’re pleased with the club as a whole, even if not every individual member is perfect. But in the second sentence, the logic stumbles. If there’s only one club, of course it is a collective—it doesn’t make sense to contrast collective and individual in that case. The sentence becomes harder to interpret.

The same applies to the sacred text. The final phrase—“speaking unto the church collectively and not individually”—makes clearer sense if the divine voice is expressing pleasure in the Church, rather than declaring it to be the only one carrying legitimacy. The grammar itself seems to bear witness to the deeper truth.

So why does this matter?

Because words shape belief. And belief shapes behavior. Throughout history, countless souls have been hurt, marginalized, or dismissed in the name of religious exclusivity. Families have been torn apart. Relationships lost. Wounds inflicted.

And yet, I believe—deeply—that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a sacred calling, much like other true and living religions. They have the potential to be healing forces in the world. To be places where supreme love is made manifest. To be communities that rejoice in all truth, wherever it is found. To be assemblies of people known not only for doctrine and covenants, but also for humility, openness, and compassion.

I raise this not as a critic, but as a friend of faith. As someone who still feels the Spirit when I hear hymns sung in sacrament meeting. As someone who treasures the doctrine of eternal families. As someone who hopes we can all read a little more closely, and listen a little more deeply.

What if the holiest Spirit is inviting us not just to defend punctuation, but to seek revelation? What if Divinity is still well pleased—pleased with every soul, every fellowship, every humble offering of love and truth across the earth?

I believe this is the case. And I believe that when we make room for that kind of divine generosity, the heavens rejoice.

Michael Ferguson is an instructor in Neurology at Harvard Medical School and the Director of the Neurospirituality Lab at Brigham and Women's Hospital.