There is a superfluity of grace in the universe. More flowers bloom than will ever be seen and savored. Nature will go on constructing trillions more snowflakes than math can predict or envision. Ten million functionaries in a million municipal offices do daily diligent work for which families in the local park and patrons in the public library and bikers on the Wasatch Back may never pause to say thanks. And mothers and fathers will continue to be reservoirs of more forgiveness than their children will ever petition for. Each act of grace, performed by good persons everywhere, replicates what the created world and its creator God enact: a superfluity of grace. Christ doesn’t give us only as much sunlight as we need; nor does he apportion his love to our capacity. Both overflow our bounds. Do we do likewise?

Christ asked us to take up our cross and follow him. Not to take up his cross, but our own. The cross of Christ represented an infinite disproportion between what he deserved and what the world gave him. We, therefore, are forewarned that we, too, will be called upon to practice an analogous grace—suited to our lesser pains and lesser capacities. But it is a grace of the same sort—the grace of forgiveness.

Evildoers we know we must forgive. Such forgiveness may come to you because that is the clear and explicit expectation the Sermon on the Mount lays upon you. Love your enemies; forgive them and turn the other cheek. Perhaps your way to such forgiveness is eased by your conception of justice—that the scales will eventually balance, the evil designs of evil men will be revealed, and the righteous will be justified and rewarded to general acclaim. Though it seems more likely to me that the call to imitate Christ means we must forsake our hunger for retribution, annihilate any satisfaction via deferred schadenfreude, and forgive as a mother her child—without secretly harbored caveats or preconditions.

Ironically, we may find it harder to forgive the good people who do us—or those we love—harm. And there are valid reasons why that is so. We have higher expectations of “the good” (whatever we mean by that inevitably employed category). Our disappointment is more acute. They should know better. Why aren’t they listening to the same spirit that I am? The logic may be analogous to the case of heretics in religious history. Pagans and infidels did not feel the fires of the Inquisition. The real fury was reserved for those we expected more of, for those who betrayed the family of faith, who twisted the true God into a vehicle for their own ideological agendas.

Forgiving the good is harder as well because we can find no solace in justice. God will not smite, and we presume that conscience will not afflict, those who with sincere intent did unintentional but nevertheless real harm to us. This is inevitable in a community where we all rub shoulders, all working for the same end, but all “seeing through a glass darkly.” The reference in Paul, of course, was a warning about the difficulty of clearly knowing ourselves, not our neighbor (“glass” is a looking-glass). Good intentions may mitigate the guilt, but not the harm, of some of our actions. How do we navigate suffering such hurt—especially when the hurts are repeated, our recourse non-existent, and the damage profound? Our hearts cry out, yearning for a celestial referee to call foul, but no commandment was broken other than the standard of sound judgment.

And then we remember, if we are fortunate, the superfluity of grace that discipleship requires of us. All may not even out, in this world or the next. As we will receive far more than we merit (“as much as we are willing to receive,” scripture tells us), so we are called to forgive far more than our offender may deserve.

And if we are humble enough—we may respond by seeing more clearly our own role in a universe full of disproportion. My authority, small as it is, my place in hierarchies of several kinds, may give me powers that to me are slight but to someone, somewhere, sometime, are consequential. Grace abounds. But let us not be profligate in drawing upon the holy resource of mercy—or making others do so.

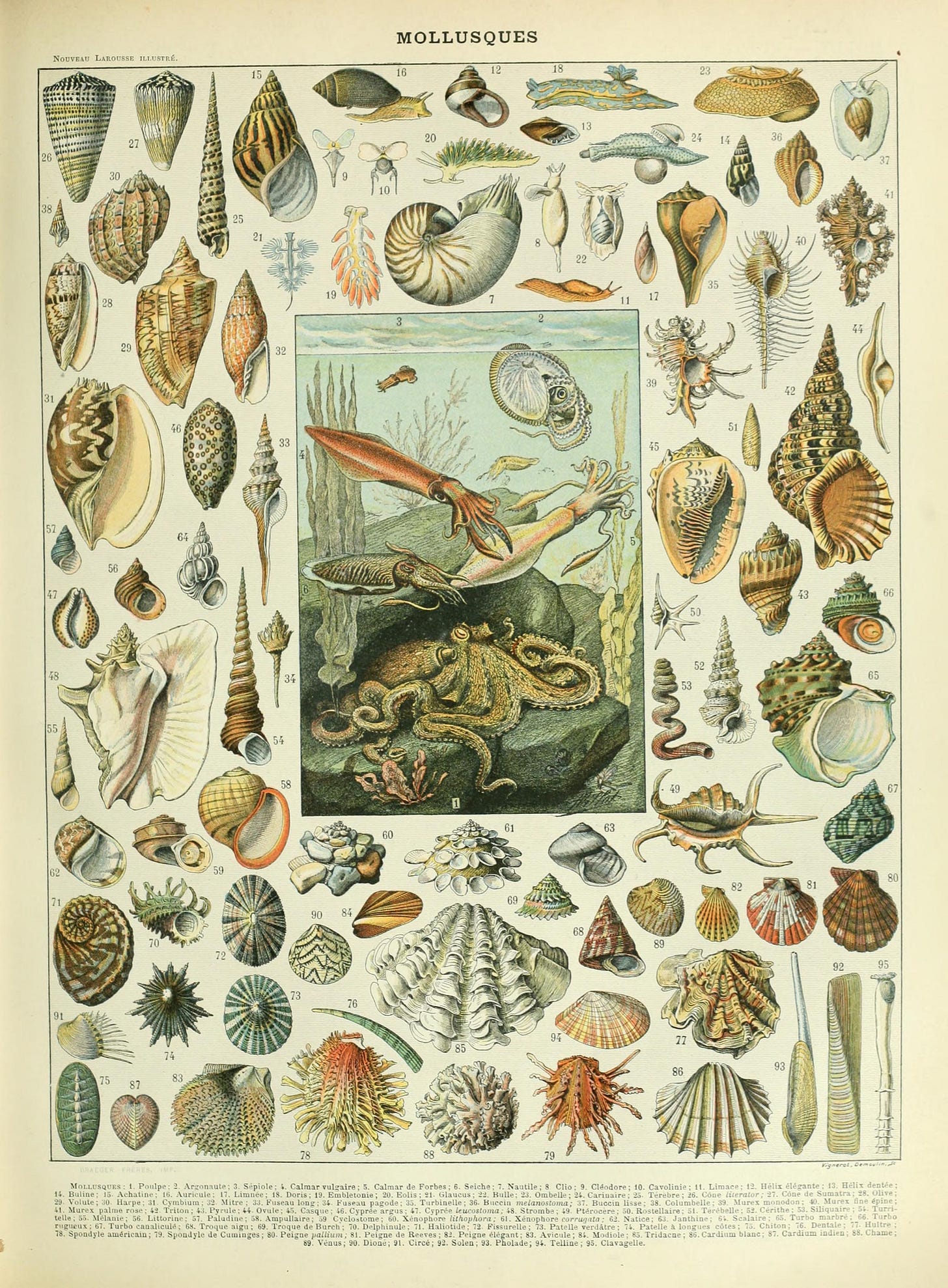

Artwork by Adolphe Millot

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."