The Night Manager

Love for the Lost and Lonely

“There's a lot of background noise. Will you turn off your phone's speaker?” Gary asks.

I set the chef's knife on the cutting board and picked up my phone.

I see his location, his picture hovering over Macey's Grocery Store. Unusual. He is not the kind of guy who stops on the way home from work at a grocery store..

“Almost there,” he says, “just driving by the temple.”

I laugh and hang up on him.

This has become a family joke; for a time, our Wi-Fi was even named “Driving by the Temple.” Gary always says that when he's running late. At first, you think he means the temple by our house, but there are four temples between the hospital and our home.

I pick up the knife and chop a few celery stalks before he enters the front door.

I give Gary a full, toothy smile.

He's battle-weary but tries to return one as he trudges up the stairs.

“You hungry?” I ask.

“No. I just ate a Kong Kone,” he says.

Ice cream? Gary doesn't have a sweet tooth, and he doesn't even like chocolate. Something is wrong.

I follow him into our bedroom. He beelines for the leather chair and slumps down in it. He loosens his tie and tugs it through the collar of his shirt.

I sit on the Moroccan pouf before him and ask what's wrong.

He leans forward and rests his head in his hands. I glimpse his once young, boyish face as his eyes brim with moisture and his crinkles become pronounced. “I am so sad.” His mouth twists as he works to keep his voice steady.

“My patient died.”

How well did he know this patient? Because of privacy concerns, I can't ask any questions I want to.

I lean forward and put my hands on his knees. “What were they like?”

“She was in her sixties. No family. No friends. No one.”

He pauses.

“She was afraid and didn't want to die alone.” His voice choked with emotion; he bowed his head, cleared his throat, and said, “I stayed with her.”

I look at the crown of Gary's head. His dark hair is scattered with silver. He rarely lets me see the burden his palliative care practice places on him. He is often late and struggles with being on time because he cares about people.

Our family and his coworkers have a love/hate relationship with this trait. Six of the eight children in our family still live at home, and the omnipresent schedule and the quotidian details of our lives create a home filled with crisis management. The episodes of who took what without asking and breaking house rules always seem insignificant compared to Gary's work—walking his patients to the end of their lives.

“It's good you stayed,” I say as I run my fingers through his thick hair. I hope he can sense the tenderness I feel for him.

A deep ache of sorrow for his patient lodges in my heart as I try to imagine a life like hers, a void where I would have no one at all. At first, it seems unfathomable to be alone during the final moments of mortality.

I scan my memories, finding ones stamped with fear, loneliness, and deep sorrow, to empathize better.

The night at Mt. Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, all alone, my stillborn daughter, Ava, still inside of me, waiting to be born, my husband and extended family far away in Utah and Arizona.

These moments can make me bitter or carve out a deep cavern in my heart that I can fill with empathy for others' burdens.

With my well of empathy full, I wonder how Gary can do the sacred work of walking people to the end of their lives daily, something he has done thousands of times.

He exhales and raises his head to look me in the eyes. “I'll be fine; I just needed some time.” He stands and unbuttons his shirt as he walks toward the closet.

I'm concerned about the toll on his health, mental and physical. And I also believe this work has molded him into a compassionate outlier.

“Go sit on the balcony. I'll be right back,” I say.

I shut our bedroom door behind me, hoping the kids won’t disturb him.

Walking downstairs, I hear teenage boys' voices as Karl and Bryson rummage through the pantry and refrigerator.

“Where were you guys?” I ask.

“Skating in the shop,” Bryson says, with his mouth full of cheese and crackers.

Our boys and their half-pipe took over Gary's shop last year. Once, it was a detached garage where Gary could decompress by welding or using a forge or lathe. We mistakenly told the boys they could put a half-pipe in there if they earned the money. Instead of earning money by mowing lawns like we expected, they posted on their Instagram stories that their friends could skate in the heated shop during the winter if they contributed cash. The boys raised the $3,000 they needed in less than a week.

“Is my dad home?” Bryson asks as he picks up a lime wedge off the cutting board and squeezes it onto the counter.

I don't confirm or deny.

“Yo, Gary's home?” Karl asks. My kids call him Gary, Gar-Dawg, or Gar-Bear. Karl sneaks chopped celery from the prep bowl, and both boys head for the stairs.

I harsh-whisper, “Hey! Don't go upstairs; his patient died.”

They look at each other, their eyes wide. I know they don't grasp what a palliative care physician does.

Gary doesn't tell those stories to them. Instead, he regales them with bedtime stories from his time as an ER doctor in Nome, Alaska.

Karl tags Bryson's arm with his elbow, “Skate or tramp?” Redirected, they bound outside to jump on the trampoline.

I slide the limes into the citrus squeezer, and the cloudy juice falls into the cup. I add ice water and take the fresh concoction upstairs to Gary, who now sits on the balcony, eyes closed, shirt off. I hand him the drink, thinking I will slip downstairs to finish making dinner.

He takes a sip and says, “People get to the end of their lives and realize they've valued the wrong things—usually money.”

Leaning against the door frame, I decide dinner can wait. I listen and watch, mesmerized by our roof anemometer's languid spin, as it measures the speed of the breeze.

The fuzzy stuff on the edges of our lives is life.

“Relationships are all that matter,” Gary says. “They are everything.”

I nod in agreement, not wanting to break the spell of pondering.

He rests his cup on the arm of the Adirondack chair.

“Everyone wants the same things. We want to be surrounded by people who love us. We want to leave a legacy.”

I don't want to interrupt. Gary rarely shares his work. But I need clarification.

“What do you mean by legacy?” I ask.

He looks at me and says, “We want to know that our lives matter.”

He takes another sip and swallows as he looks toward Mahogany Mountain. I see the striations of granite amid a patchwork of verdant green and golden brush.

“Advanced cancer is the great equalizer; it brings suffering, loneliness, and death.”

He rests his legs on the iron railing.

“No matter somebody’s status or belief system, they become very introspective and wonder what has been left undone. They evaluate their lives and their relationships. Some have more joy. Some have more regret. Everyone goes through the same process.”

“Everyone?” I ask.

We watch the reddish hue of alpenglow on the mountains.

“Everyone wonders if their life mattered. I see some of the greatest suffering among people who are quite wealthy, who have paid others to do the unmentionable, the scut work. Their lives have been sterilized because they can afford to pay someone else to do it. Then, they find they can't pay someone to suffer or die for them. When it comes to dying, you are coming face to face with your inner joy and inner demons, and sometimes the privileged suffer the most because they are not accustomed to it.”

Seems plausible. I think of acquaintances who believe their minor troubles are “so difficult and complicated.” And those are the most challenging things they have ever faced. Hard is hard. Hard is a sliding scale.

Gary continues, “We want to know who came to our aid: coworkers, friends, family.”

He swirls the remaining ice around his glass. The boys flipping on the trampoline pull him further out of his mood.

“Whose job is it that we care for someone else?” he muses.

His question does not elicit a verbal answer from me.

We already know. Family. Friends. Community. In that order.

“What if I'm the only one bringing them dinner?” His voice falters.

Long ago, my mother brought dinner to the widows in our congregation. She would ask me to ride along and hold the tray: a plate of pan-fried steak, boiled peas, and potatoes, an iceberg lettuce salad with carrot shavings, a splurt of Thousand Island or Catalina dressing, and a separate cup of red jello. My mom would linger and engage the widows in conversation more nourishing than the food.

Gary pulls me back.

“This homeless woman was alone. I got to know her over the course of a month or so. Then, she received a new diagnosis and was transferred out of the hospital to a care facility. No one knew her there, and she didn't bond with anyone; she was no longer on our service. She didn't have anyone. The facility called me, and I went to be with her. She was utterly alone. Only one person knew she was alive,” he says.

The tears slip down his face.

I crouch at his eye level and ask, “Who knew?”

“The night manager at a fast-food restaurant was the only one!” Gary clears his throat of emotion again. “For a month, she gave the woman the misordered meals and a warm place to sleep on a bench in the back seating area.” He shakes his head in disbelief. “The dying woman signed over her end-of-life decision-making rights to the night manager. And the kind woman had no idea.”

We weep together for the woman, alone and afraid to die.

Bridget Verhaaren holds an M.F.A. in Creative Nonfiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts and a B.A. in English from Brigham Young University. Together, Bridget and Gary have eight children and enjoy spending time outside with their VEGA (Verhaaren-Garner) Family.

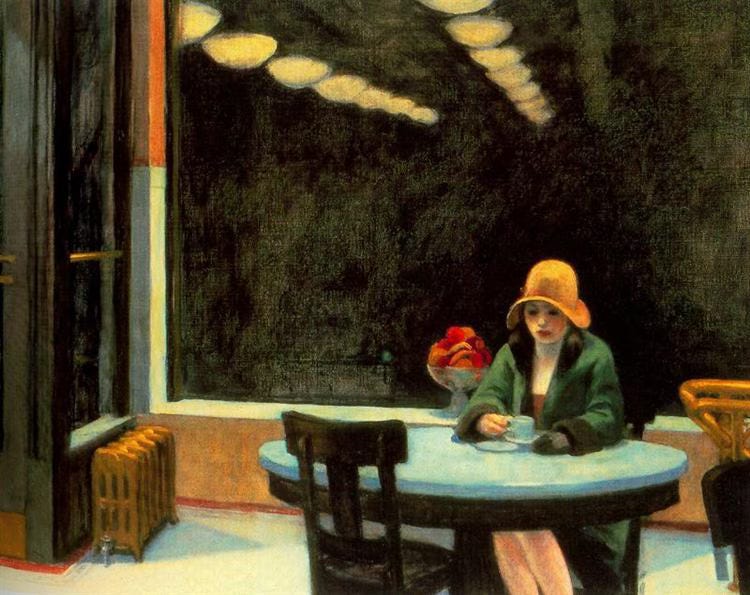

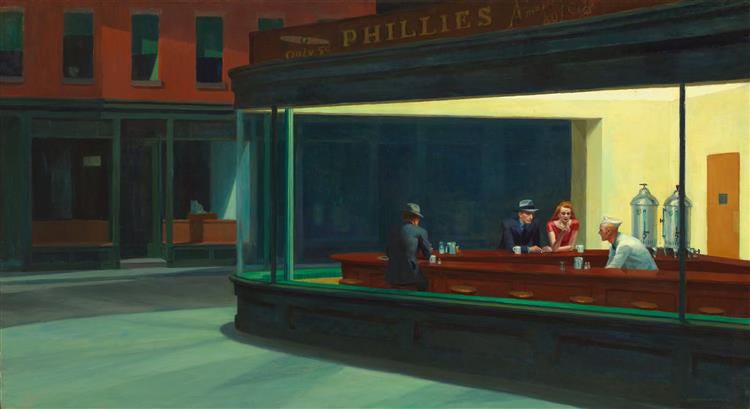

Art by Edward Hopper (1882-1967).