The Mysteries of Mind

A Book Review of David Bentley Hart's "All Things Are Full of Gods"

One of the baseline assumptions of polite society is materialism, specifically the belief that all real phenomena can be explained through reference to the physical world (the interactions of leptons, quarks and energy). This is easy enough to accept, and seems true on certain levels. No one is astounded when a dropped rock falls instead of floating, or when a buildup of electrons produces a lightning bolt. However, there is a fuzzier area of conflict, where materialist assumptions begin to rub up against human perceptions of ourselves and our world that seem innate, almost beyond debate.

Philosophy of the mind is such an area—a strange branch of knowledge, focused on questions of consciousness, mental cognition, qualia (subjective, conscious experience), and related phenomena. Despite all the academic jargon, it is surprisingly intuitive; all it asks for is reasoning, careful observation of internal thoughts, and the natural deductions that arise from these observations. Still, investigating a new field is always easier with an introduction, and David Bentley Hart’s All Things Are Full of Gods: The Mysteries of Mind and Life is an excellent mid-difficulty foray into this section of human knowledge. And, more importantly for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I found it to be an exciting invitation to return to our early Mormon heritage of material and spiritual mysticism. The book unpacks the undergirding assumptions of our largely materialist computer age and provides alternatives that feel instinctively correct. And yet, despite Hart’s skillful refutation of these material premises, his book leaves us free to choose which world we wish to live in: one totally comprehensible, but dead at the heart, or a world full of wonder, spirit and mind that is immaterial, and thus ultimately incomprehensible in human terms.

I have always read a reasonably eclectic selection of books. All Things Are Full of Gods is nonetheless one of the strangest books I have read this decade. It is a Platonic dialogue, meaning it reads like a transcription of a conversation rather than a work of philosophy or nonfiction. The conversation is between four retired Greek gods debating ontology, epistemology, physicalism, and spiritualism. One, Hephaistos, takes up the fight for materialism. The other three, led by Psyche (Greek for soul), represent the view that mind (or perhaps spirit), rather than matter, forms the basis of reality.

The Platonic dialogue format has notable strengths: Regardless of how artificial and structured the conversations may be, the back-and-forth makes the academic dialogue easier to follow than reading dueling theses or treatises. At times it’s also legitimately funny, as when, after Hephaistos’ gibe about Eros’ mother Aphrodite (who is also Hephaistos’ oft-straying wife) is thrown back in his face, Hephaistos sheepishly admits that their “marriage counseling has been going quite well as of late.” The dialogue also forces a full presentation and defense of the materialist assumptions that underpin modern life, rather than a “straw man” version. And while Psyche’s triumph over Hephaistos is a foregone conclusion (and you can sometimes tell, as when Hephaistos concedes too quickly in the interest of moving the book along), overall, the victory feels earned.

So, what do these characters argue about, and how does Psyche earn her victory? Psyche starts the argument with a series of claims she deduced from the experience of deciding to pick an especially beautiful rose:

[M]ental acts are irreducible to material causes; that consciousness, intentionality, and mental unity aren’t physical phenomena or emergent products of material forces, but instead belong to a reality more basic than the physical order; that the mechanical view of nature that has prevailed in Western culture for roughly four centuries is incoherent and inadequate to all the available empirical evidence; that in fact the foundation of all reality is spiritual rather than material and that the material order to the degree that it exists at all [...] originates in the spiritual; that all rational activity, from the merest recognition of an object of perception, thought, or will to the most involved process of ratiocination, is possible only because of the mind’s constant, transcendental preoccupation with an infinite horizon of intelligibility that, for want of a better word, we should call God; and that the existence of all things is possible only as a result of an infinite act of intelligence that, once again, we should call God.

Hephaistos, the materialist, disagrees with each of these suppositions, and, over the course of six days, the four gods debate these points, with citations from philosophers and scientists, ancient and modern.

As an example, one key insight, developed and reargued throughout the book, is that, as children of the internet era, we tend to think of everything as a computer, including ourselves. This makes some sense; the computer is a world-shaking invention, making what was once unimaginable (finding million-digit primes, mapping the universe), trivial. However, just as our grandparents in the atomic age wrongly analogized everything (from geopolitics to sexuality, to the atomic bomb and nuclear containment regardless of how stretched the metaphor), in the computer age, we are comparing something rich and miraculous—human consciousness—to a box of silicon wafers. As Psyche points out, we speak of computers having memory, of knowing what they contain, but they don’t really know anything. They can, through mechanical processes, display a few lighted squiggles on a screen, but it takes a conscious mind, the viewer, to turn that chaotic pattern into letters, words, and information. And by analogizing a mechanical process and a mental one, we debase the beauty of consciousness.

This is especially important in the era of AI broadly and Large Language Models (LLMs), specifically, which, though rarely addressed explicitly in All Things Are Full of Gods, hover outside and offer “a clear window into Hart’s broader concern.” Much has already been written on AI and Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment, but in essence, the thought experiment challenges whether AI, when processing inputs and delivering outputs, can really ever be said to be “thinking,” or “intelligent,” or “conscious.” Certainly, AI can follow a set of rules to turn linguistic inputs into linguistic outputs, but as Hart observes, this translation provides no evidence that there was “any semantic knowledge involved at any point in the process, and there’d be no occasion or logic dictating that such knowledge could arise from or supervene upon the process” (emphasis in original). Of course, these arguments only work if you believe that there is a meaningful conceit of consciousness, of knowledge, and of logic. Many materialists really do believe that the human brain is nothing more than a computer, and that the firing of neurons, the flipping of tiny magnetic bits, or any other method of computation are consciousness: that form precedes thought and matter precedes mind.

This book is fun, interesting, and different, and more than that, important, especially to members of the Church. But before diving into the connections to Mormon thought and doctrine, I’ll give a quick caution. While I’ve praised the book for its accessibility, that’s only in comparison to truly dense, insider texts. The book can still be inaccessible at times, casually dropping in words like “mereology,” “solecism,” and “psittacine” (“the study of parts and wholes,” “a grammatical mistake,” and “relating to parrots,” respectively). It isn’t for everyone, especially not for those who dislike grappling with abstract ideas that don’t have concrete examples attached.

Despite its density, I think that All Things Are Full of Gods is vitally important to Latter-day Saints, because it can help us reconnect with and understand anew the spiritual/material mysticism that began early in the Church and has since weakened, replaced by Protestant Christianity’s legalism. When Psyche claims “If the physical order can’t be the ground of mind, mind must be the ground of the physical order,” how different is that from Doctrine and Covenants 29:32, which claims that all things were created “First spiritual[ly], secondly temporal[ly], which is the beginning of [God’s] work.” What do we imagine when we think about spiritual creation? Is it just writing out ideas on some kind of divine chalkboard, or is it a real creating and organizing work, just one that is hard to conceive of in our material realm?

Or again, Hart is skeptical of Cartesian dualism, the idea that the two types of stuff, the material world and the spiritual one, overlap but don’t interact, as they are of distinct and irreconcilable substances. I felt myself cheering at such a rejection, thinking of God’s promise to Joseph Smith in Doctrine and Covenants 131:7 that “All spirit is matter, but it is more fine or pure.” Not too long after Descartes, Joseph Smith helped us to move again into a monist (as opposed to a dualist) world. Hart argues that spirit is primary, and the material world is derived from the spiritual one. Of course, any equivalency can be reversed, and the verse could just as easily read “All matter is spirit,” and indeed, with the primacy of spiritual creation, this may have been what God (or Joseph Smith, translating the revelation from pure knowledge into English) meant.

And beyond these literal connections to some of the more mystical aspects of our founding doctrines, I found myself asking how much we, as members of the Church, have ceded ground to the materialist assumptions that undergird Western society. For example, we believe in a God who follows laws. But do we imagine those laws to be spiritual or physical laws? Do we imagine God as having to follow, for instance, the law of gravity? Then what do we make of the Ascension (or the First Vision, for that matter)? Do we unintentionally align ourselves with Deists, who are grateful that God set up the universe in such a way as to allow only the miracles that happen to conform to the starting, immutable physical laws that bind even God himself? Or, speaking of miracles, do we foreclose certain possibilities, imagining that, as God is bound by physical laws, he will only grant us miracles that have some sort of plausible deniability?

On a more practical note, I wondered about the connections between the materialist view of consciousness inherent in the attempts to develop sentient AI and Elder Ulisses Soares’s April 2025 general conference talk, “Reverence for Sacred Things,” in which he warns of the use of AI in spiritually inappropriate ways. Certainly, at one level, he is probably warning against members of the Church generating pictures of Shrimp Jesus, or other disrespectful acts. But as he talked of reverence, and of “higher and holier things,” I couldn’t help but wonder if he was also striking at an entire philosophy, one that imagines that there is nothing above us, and that we are the mere products of emergent properties from lower, simpler matter. In that world, there is nothing worthy of reverence. But in the world Hart tries to introduce us to, while we are certainly made of matter, that matter is animated, given form, meaning, and existence by something worthy of reverence: Spirit, Mind, and ultimately, God.

As I read, I felt, flickering around the edges of the characters, hints of the enchanted world that the ancient Israelites, the early Christians, and even Joseph Smith’s family lived in, to some degree. I hope that as this book and others like it spread among modern practitioners in religion, we can feel our way, fumbling, back into the world of Spirit.

Ben Dearden is a lawyer, a husband, and a father of two sons. He enjoys writing articles, screenplays, and stories with tiny audiences.

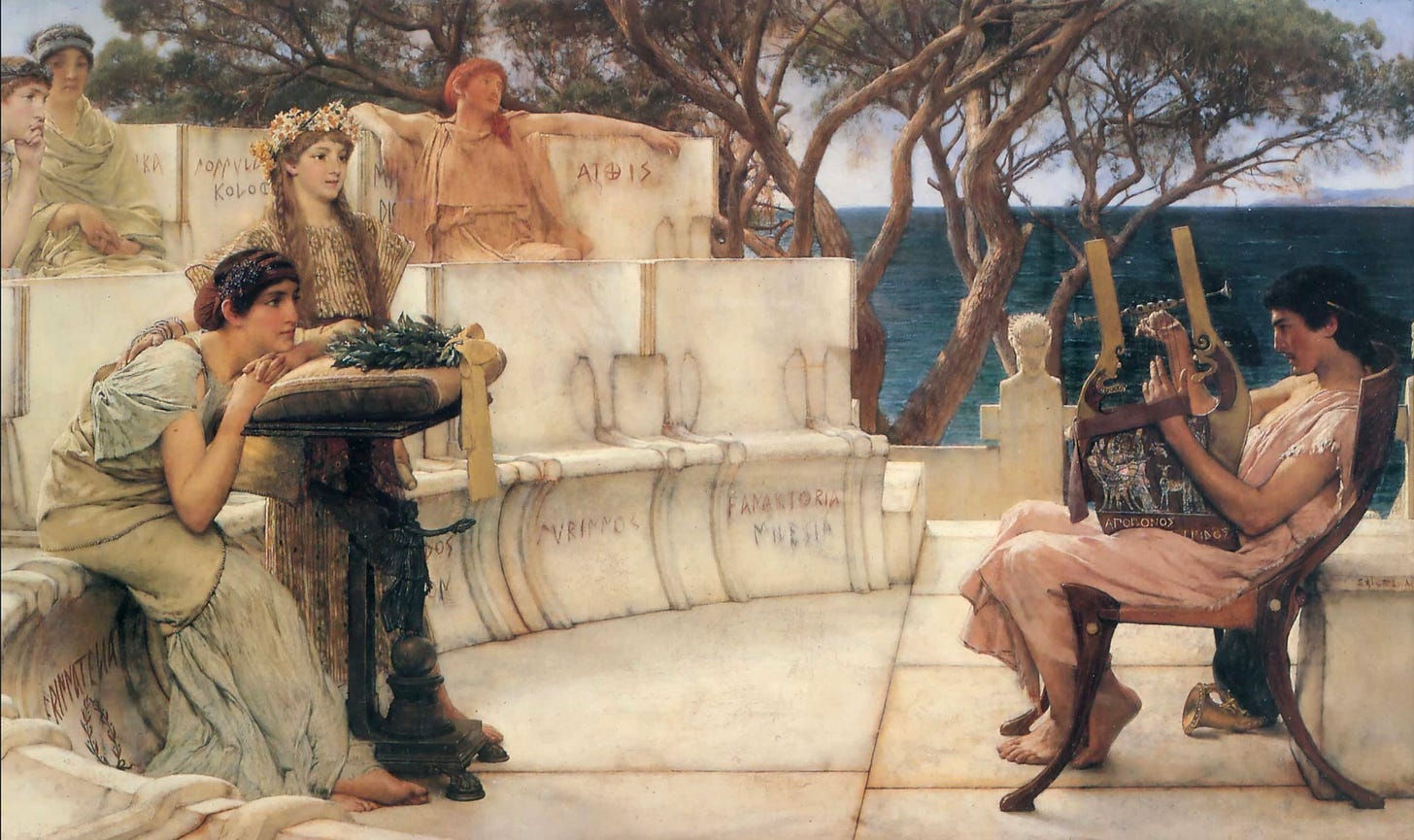

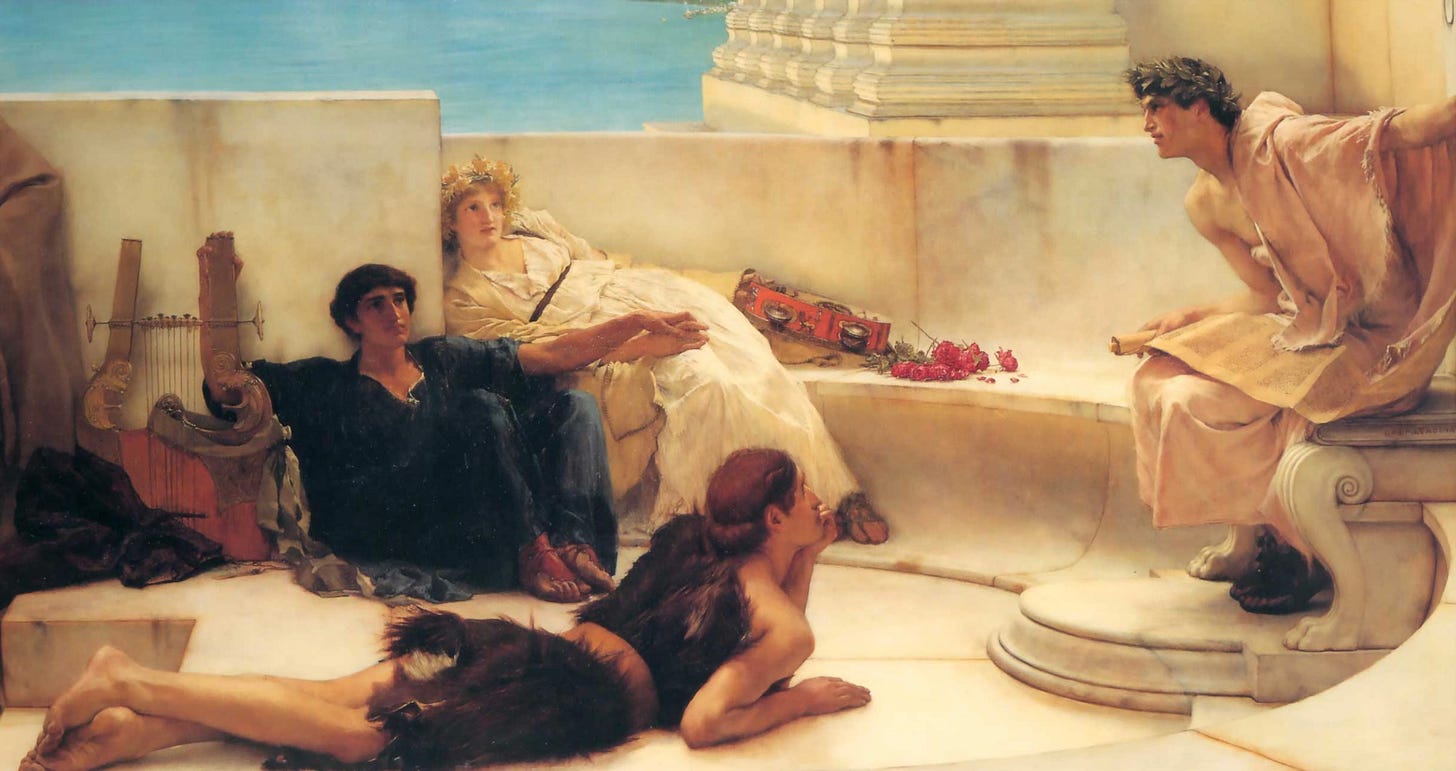

Art by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912).