The Magician's Apprentice

Words and the New Creation

What do words do?

Why do words matter?

How do words obscure or reveal?

Do words seek only to accurately convey a deeper objective reality? If so, is their accuracy all that matters?

Or do words themselves carry their own power—their own magic?

My introduction to these questions began long ago, late at night, with a curious creature called the Editing Pig.

I

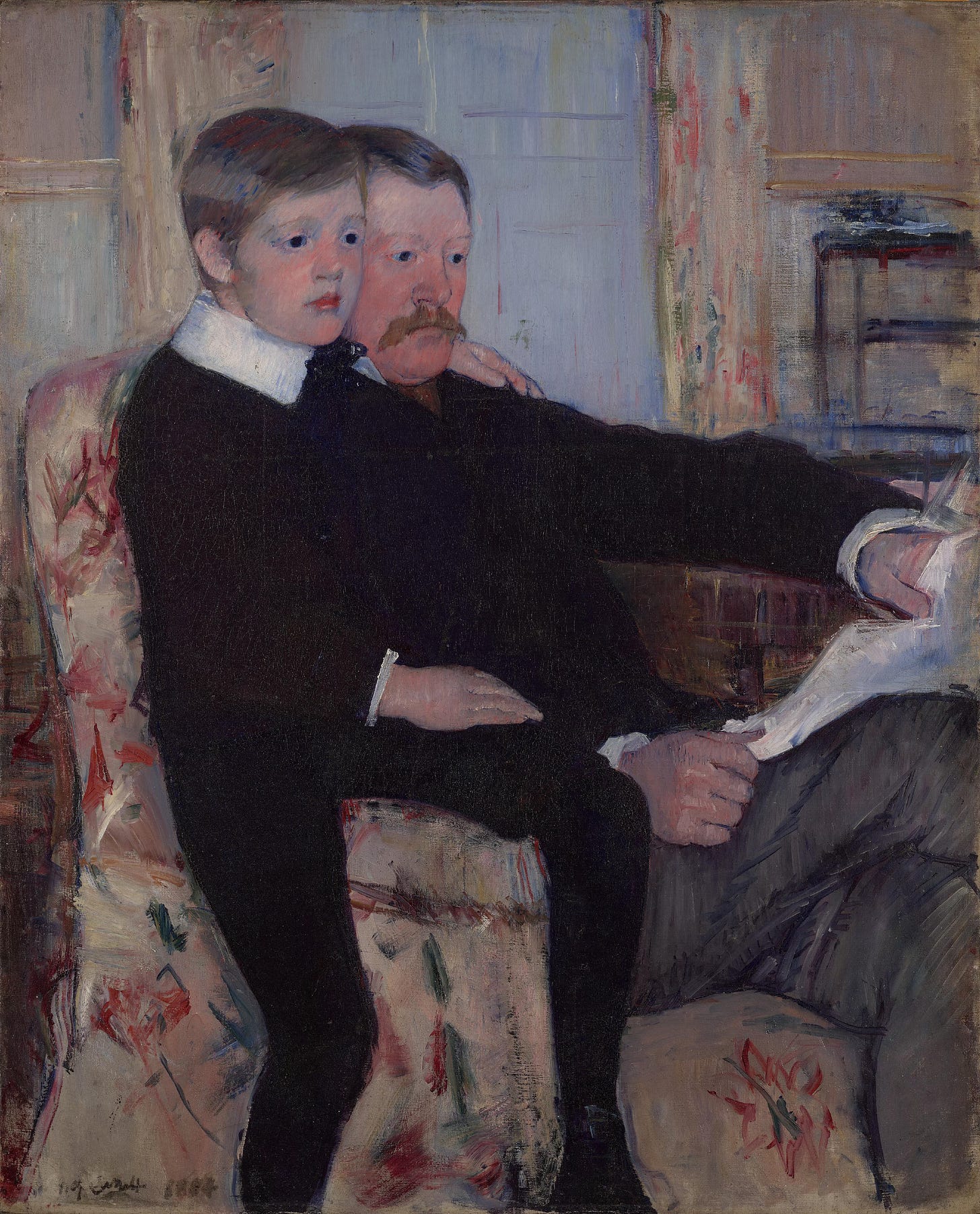

I cannot remember precisely the circumstances that led to the creation of the Editing Pig. But starting in about sixth grade, whenever I would write a paper, I would sit down with my father at his hulking mahogany Civil War desk, and he would pull out a pen and we would go through what I had written: line by line, word by word.

I would watch as he would take his pen and insert an extra word using a carrot symbol or, much more commonly, cut out entire superfluous lines. It was with a loving twinkle in his eye that my dad dubbed me the “Knight of Redundant Verbosity.”

Behind me forever is the voice of my dad, urging me to make it “half as long.”

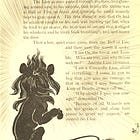

At some point, my dad decided that his recurring lessons about grammar and language were not landing with adequate force. And so, one night, attempting to more deeply emphasize an important point, and in an act of sheer absurdity, he grabbed a small, pink, plastic pig, found a minute set of yellow plastic glasses, fixed the glasses to the pig’s snout, and dubbed the whole bizarre creature “the editing pig.” From that night on, over the next seven years, I would dutifully write a rough draft of whatever assignment I had received in school, bring it to my dad‘s desk, and the editing pig would digest it—me watching—word for word.

But the pig was no passive reader. On the rare occasions I turned a phrase memorably, the pig would celebrate with excited snorts. Much more commonly, when I would misplace an adjective, or conjugate a verb incorrectly, or leave on the page a pronoun whose antecedent wasn’t clear, I would be met with derisive oinking, as if the pig were somehow the arbiter of how English ought to be used.

And the pig also taught me that sometimes bad language is genuinely dangerous. Occasionally, if the editing pig came to a particularly offensive run-on sentence, he would start to seize, my dad making him fall prostrate on the green felt surface of the desk. More than once, my poor father had to perform CPR on the lifeless plastic animal right there—until I figured out how to cut the offending sentence down to a reasonable size.

This phenomenon is so bizarre, and it was so perfectly effective and affectionate, that I don’t even know how to interpret it. During those late night sessions—filled with teasing, laughing to tears, a sore side, and a consistently deepening bond with my father, a sense of the gravity of what we were doing settled deeply into the marrow of my bones. Yes, I learned a fair bit about language, its rules, and its uses. But the more important lessons lay far beyond grammar. As I reflect many decades later, I realize that at least part of the real magic of what was happening was not a story of adverbs, nouns, and sentence structure, per se, but rather that I was slowly learning the way to allow words to reveal or even create a shared reality. The very hardest thing that words do, after all, is to bring a reader and a writer together in such a way that the words themselves show the reader the reality of the writer’s heart. Writing and reading, in their very finest moments, are thus acts of atonement, and a form of healing that both reflects and transcends those little squiggles on the page.

II

I stand behind a friend who has asked for a blessing. He is facing a complicated set of questions and is hoping the blessing will provide guidance beyond what his own studying has revealed. As has become my custom when I’m asked to offer such words, I invite both of us to begin with a moment of silent, inaudible prayer—he to articulate what he hopes for from the blessing, I to seek guidance from heaven as I pronounce the words.

Then, after both our prayers have concluded, I gingerly place my fingers atop his head. I begin quietly: “By the power of the Holy Melchizedek Priesthood which I hold, and in the name of Jesus Christ, I offer you a blessing.“

What happens after that invocation? What, exactly, is the process by which the words flow from my mouth? What do I hope that process will be? What should it be? Despite my love and care for words, I do not know and cannot precisely tell.

I wonder, for example: when I pronounce a blessing, do the words themselves matter? Am I supposed to say a certain thing a certain way? Do the words I speak only reflect—or do they actually shape—reality? If they are descriptors only, how can I communicate the most truth? If, on the other hand, they shape as well as reflect what is real, then must I say certain words in a certain way for God’s will to be done?

Simultaneously: how much do words matter to the listener? When we ask for a blessing of comfort or direction are we really looking for words anyway? Or do we simply seek peace or comfort or some other divine emotion? Is it possible that blessings are mostly about conveying love—or do the words themselves really matter?

Though I love words, I can’t fully bear the idea that the efficacy of a priesthood blessing depends upon a precise parade of words. The responsibility would be too much. And yet, I am likewise uncomfortable with the conclusion that the words don’t matter. After all, don’t I hope that my many hours and years of studying words might allow me, someday, in some moment of need, to deliver words that sparkle with beauty and that convey truth uniquely? Do I not hope that part of what my father was preparing me for in those many hours spent perched at his desk was precisely the ability to use words to bless and to heal? And if words can be a conveyance or even a catalyst for atonement, then wouldn’t a blessing be a uniquely poignant moment for such atonement to occur?

One November a few years ago, I was passing through a prolonged period that felt like a light-less, comfort-less empty steppe. I wondered, very honestly, if things could ever get better. In the midst of that suffering, I sought a blessing from a beloved friend, in which he promised me that somewhere up ahead awaited “the sunny uplands of the soul.” That same sentiment (which, of course, did not originate with my friend) could be expressed in a thousand different ways. And yet, those precise syllables called to my mind an imagined—but as yet unimaginable—future that summoned to my heart a salve of beauty and hope that otherwise might have eluded me.

For me, in that moment, words mattered.

Similarly, I have faced many moments while looking for the answers to deeply complicated personal questions when I have opened the scriptures and stumbled on a verse that seemed to hold just the insight I needed at that moment. This is such a common story in our culture that we hardly stop to think about how it works or even what, exactly, we think might be happening there.

But let’s unpack this for just a moment.

Am I to believe that when Joseph Smith translated words in the Book of Mormon, or when Nephi (or whomever) first wrote them, that one of them somehow sensed that I would need precisely those words in 2025? That seems unlikely. But if not: then what part do the words themselves play in my moment of inspiration? Maybe this is a question of needed inspiration being built from whatever raw materials present themselves. Perhaps, if I had not been reading those verses, some heavenly whisper would have made do with other words or other phrases or other means of communicating the same truth, something that would have been equally effective but conveyed with a different phrase and coming from a different messenger.

But that’s precisely the issue: wherever the words came from, and however they arrived at my heart and mind, I have relied on and found strength in the words. At moments when I have questioned my decision, or wondered if I did what was right, I have gone back to those words. I have flashed to precisely that idea and, somehow, in a way still inexplicable, have found some comfort and confidence in the knowledge that a way was prepared.

III

Because these experiences constitute one foundation of my spiritual life, I am brought back relentlessly to that same series of questions: what are words? What can they do? Where do they fail? And what connection do they bear to the divine?

The endeavor that has brought me closest to the answers to these queries is, perhaps surprisingly, the practice of medicine. This is somewhat paradoxical because, in 2025, medical technology has advanced so far and is progressing so fast that one could be forgiven for thinking words have become superfluous. After all, we live in an age where microscopic metal tubes can swiftly prop open a clogged heart artery and where a person’s own immune cells can be siphoned from the body, “taught” to recognize and fight cancer cells, and then be reinserted so they can attack a malignancy while leaving normal cells alone. Amidst all this, it would seem intuitive that words might have become the relics of a bygone era—artifacts of a simpler time that have come to occupy a place of secondary, if any, importance.

And yet.

When I was a resident, I helped care for a patient who was deeply and irreversibly ill. The patient was fairly young and his family was terribly distraught. While the patient languished and suffered, the family became increasingly frustrated with each other and the medical team. Finally, we called an “all hands on deck” meeting for half a dozen doctors and twice that many family members to discuss the situation and a way forward.

As a resident, I did not have much to say in this meeting. I sat, nearly silent, in a corner and watched as a skinny grey-haired attending physician—all wrinkles and angular limbs—wove words together as if he were weaving magic from the air. He approached the patient’s coming death with candor, yet somehow also with grace. He communicated deep medical complexity with complete honesty, and yet in a manner that seemed entirely comprehensible to all those present. He demonstrated pathos and compassion even as he also evinced steely resolve and confronted without blinking the hardest questions of mortality, limitation, and death.

And somehow, as he spoke, the mood in the room palpably eased—from my little corner I watched as muscles relaxed, faces smoothed, tears flowed, and hearts almost visibly softened, and all of this happened in real time. What to this day still strikes me about that moment is that, between our entering the room and our leaving it, “nothing happened.” No one so much as touched the patient, and the patient’s life was not somehow miraculously extended. Indeed, no one touched any of the family members, either. Yet, ineluctably and unmistakably, in those moments the world—for that family, facing that most terrible of circumstances—tilted on its axis.

And how could that change have come? After all, that physician’s words were nothing more than a certain kind of vibration that propagates across molecules in the air. What possible effect could those vibrations have in a moment as dire as that was? But somehow that physician, simply through his words, was able to elicit real molecular changes in those who heard them such that if we have been measuring in real time, we would have seen a lowering of blood pressure, a slowing of heart rate, and a decrease in the level of cortisol and other stress hormones. Somehow, the words themselves actually pushed and pulled molecules, altered neural pathways, fired synapses, loosened the hold of the heart on emotions, and altered the very experience of reality of those who heard them. Though I have no sense whatsoever of any religious convictions that physician might have held, still, I can’t think back on that memory without recognizing that in speaking he was cinching together what reality had rent asunder. He was taking what had been divided and weaving together back into one.

It may be, as Joseph Smith wrote, that words are but “a little, narrow prison,” and that all our words together constitute “a crooked, scattered, broken, and imperfect language.”

It may also be, as Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that: “We but half express ourselves and are afraid of that divine idea which each of us represents.”

I acknowledge all of this.

And yet, the sentiments of Emerson and Smith remind me of a word that proves particularly slippery in modern English: magic. By “magic” we can mean very nearly opposite things. On the one hand, when we know we are being deceived, we may say “we all know that’s not real—it’s just a bit of magic.” In that context, the word connotes duplicity, even dupery. Yet in other contexts we look at something in wonder and say, struck with awe, “Oh my gosh, that was just like magic,” the word connoting not deception but something too grand for us to easily understand.

And that distinction aptly captures the reality of language. Smith and Emerson remind us that language can sometimes be smoke and mirrors, a poor person’s feeble attempt to convey the full majesty of reality through meager vibrations and squiggles. Yet my experience—as a parishioner, a friend, a son, a writer, and a doctor—suggests to me something more like the second understanding. What most strikes us about words is not their limitation, but their power; not their impotence but, well, their magic.

I return, in my mind’s eye, to my father’s office thirty years ago. From an angelic remove, sitting up near the ceiling, I can imagine myself staring down and seeing, huddled behind the hulking desk, a father and son, paper on the desk’s green felt surface, pen perched ready in the father’s hand, plastic pig poised at the ready. And as my father moves through conjugation, active voice, verb selection, and subject/verb agreement, as he exhorts me to make it “half as long,” and, yes, even as the Editing Pig falls into cardiac arrest as a sentence twists and turns, I can all but see a glow emanating from behind the credenza. What was happening, after all, was not just assignments, not just essays, not even just writing—it was, instead, a master wizard and his novice apprentice. It was me learning to weave spells from letters and words, learning to craft incantations from sentences and paragraphs. It was me, without really knowing or understanding, becoming one: with the father who was teaching me, the words we were revising, the reality they represented, and the beauty they sought to bring into the world.

Mystery abounded: my dad was teaching me magic.

With words, we call into existence not simply a pale shadow of some other reality, but a distinct reality itself. Words matter for their own sake—because they can call down the powers of heaven, because they can bind in heaven what is bound on earth, because they can move molecules and open arteries, and, finally, because they can both create and convey love. Words speak truth and beauty and, in their very best moments, words can make us one.

Tyler Johnson is a medical oncologist and associate editor at Wayfare. He dedicates this essay to the Magician himself.

Art by Edgar Degas.

This essay is part of On the Road to Jericho, a column by Tyler Johnson. To receive this column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for On the Road to Jericho.

See his latest column here:

WAYFARE EVENTS

The Angel

Join us for a screening of The Angel, a film by Barrett and Jessica Burgin. Afterwards, there will be a discussion of the film and LDS filmmaking in general with Barrett Burgin, Joshua Sabey, Sarah Perkins and Theric Jepson.

NEWS

The Mormon Scholars in the Humanities (MSH) Board now seeks a dynamic new Executive Technology officer to join as a Board member. We encourage applications from the broadest set of people with humanistic and technical interests.

Beautiful. I saw the magic happen as your father's study appeared, and the editing pig fell on it's side. I sat, head bowed, with hands on my head, listening for the right words. My heart slowed in the hospital room. I smiled with joy at the love of words. True magic!

Thank you for writing these words - they are filled with magic!