The God Who Sees

One of the most difficult aspects for me to reckon with when reading the Old Testament is that, while these are literary stories communicating a larger message about God, many also portray human experiences in which God appears to command or condone things I believe are deeply immoral. How can we simultaneously find devotional value and literary power in a story while strongly condemning immorality and naming what’s wrong as unequivocally wrong? Should we even try?

Such is the case with the story of Hagar, Sarah, and Abraham in Genesis 12–22. It is a story with aspects I find deeply moving and inspiring, while also feeling morally repulsed by the enslavement and abuse of Hagar, the use of Hagar’s body to give Abraham and Sarah a child, the endangerment of Ishmael, Hagar, and Sarah by Abraham, and the binding and near-sacrifice of Isaac. Though I am aware that some of these actions were permitted by the culture of the time, I believe these things are wrong—even morally abhorrent. I believe God does not ask parents to kill their children (even as a test or lesson), God does not ask us to sacrifice or endanger another person even in the pursuit of a worthy goal, and abuse is never even tacitly endorsed by God.

At the same time, I find that when I zoom out and look at Genesis 12–22 as a whole story—including the hard, immoral, repugnant parts—it has the capacity to tell a compelling and moving narrative about a God who is deeply invested in deliverance and human dignity.

Let me explain what I mean.

Abraham’s story in the book of Genesis is the beginning of a story about how God’s covenant people came to be—how the descendants of Isaac and Jacob/Israel came to be God’s chosen people, how they came to occupy their promised land, why they should continue to be there, and what God wants them to do and become. Within the story, over and over God’s promises to Abraham seem delayed, in jeopardy, or just plain impossible to fulfill. It isn’t hard to imagine that as this story was told and retold by an exiled people waiting again for these promises to be fulfilled, it would have had particular resonance and importance.

And while these chapters might at first seem like a series of meaningful but random anecdotes (with a few odd duplicates), a closer look at the text reveals literary intention in their selection and arrangement. The editors and redactors of the book of Genesis preserved important cultural memories, but they also used literary and rhetorical techniques to communicate larger themes and ideas. In these chapters we can find a chiasmus—a literary device that places themes in ABCBA order, and that is often used to draw attention to what is at the thematic center of the story. What I discovered as I looked at the literary structure of Genesis 12–22 is that at the heart of Abraham’s story is, paradoxically, Hagar’s story—a story of oppression, of finding God in the wilderness, and of naming God as the God Who Sees.

Placing Hagar’s story at the heart helps us see what the chapters taken together as a whole might be trying to communicate, which helps us read with wisdom and discernment.

Chiasmus in Abraham’s Story (Genesis 11:27–22:24)

A. Prologue/Genealogy (11:27–30)

B. Abram challenged to let go of his family of origin; God promises blessings (12:1–9)

C. Sarai and Abram in danger; God protects and delivers (12:10–20)

D. Abram separated from and contrasted with Lot; Abram rescues Lot; God’s promises to Abram reiterated (13 & 14)

E. Abram questions; God reiterates promises and performs a covenant ceremony (15)

F. Hagar’s story (16)

E. God reiterates promises; a covenant ceremony/ritual is performed; Abram (now Abraham) questions (17)

D. Abraham separated from and contrasted with Lot; Abraham rescues Lot; God’s promises to Abraham reiterated (18 & 19)

C. Sarah and Abraham in danger; God protects and delivers (20)

B. Abraham challenged to let go of his future family (Ishmael & Isaac); God’s promised blessings are reiterated (21 & 22)

A. Epilogue/Genealogy (22:20–24)

A. Prologue/Genealogy (11:27–30)

Abraham’s story picks up right where the Tower of Babel story leaves off. The placement reminds us that though humanity has repeatedly failed to carry out the commission God gave humankind at creation—to multiply and replenish the earth, to be the image-bearers of God and to bless to the whole world—God has not given up. God is going to try again, this time starting with a single family, chosen (in the Genesis account) seemingly at random rather than for any particular righteousness (as Noah was).

B. Abram challenged to let go of his family of origin; God promises blessings (12:1–9)

God’s initial invitation to Abram is to leave his father’s family and his homeland behind, and to accept God’s promise of a promised land and of becoming the father of a great nation and a blessing to the whole earth. Abram obediently departs, bringing with him his household, including his wife Sarai and nephew Lot. Though his “promised land” is currently occupied, he is reassured by God that his offspring will inherit the land and he builds an altar to mark the spot.

C. Sarai & Abram in danger; God protects and delivers (12:10–20)

God’s promise to make of Abram a great nation is almost immediately threatened, as there is a famine in the land they have been brought to, and they flee to Egypt. There the promise is again in jeopardy as Abram believes his life (and thus, God’s promise) to be in danger. By telling Pharaoh his wife Sarai is his sister (the text in Genesis is ambiguous on if he is lying or telling a half-truth, and on if this course of action is endorsed by God or not) and encouraging Pharaoh’s sexual interest in her, Abram endangers both his wife Sarai and their future family. God sends plagues to Pharaoh’s house, delivering Abram and Sarai from danger and setting them free to return to their promised land. (Familiar Bible readers will note the foreshadowing of what will happen to Abram’s future family here.)

D. Abram separated from and contrasted with Lot; Abram rescues Lot; God’s promises to Abram reiterated (13 & 14)

Here Abram separates his household from that of his nephew Lot, and God again reiterates the promise of uncountable offspring and a land of inheritance for Abram. We also see a contrast between Abram and his nephew: While Abram acts in generosity and wisdom, Lot is foolish, soon in danger, and needs to be rescued by Abram.

E. Abram questions; God reiterates promises and performs a covenant ceremony (15)

Here we once again see God reiterating God’s still-unfulfilled promises to Abram, and for the first time we see Abram pushing back and questioning God (some translators even read Abram as interrupting God with a question here). Notably, God’s response to Abram’s questioning is not to condemn or to withdraw the promise, but to consistently reassure and reiterate God’s promise to Abram. The account in Genesis tells us that Abram believed God (the Hebrew word denotes trust in a person or a relationship, rather than intellectual agreement), and that God counted this as “righteousness,” which we might understand as being in “right relationship” with God.

Again Abram is reminded of God’s promise to give him a land and an inheritance, and again—even in, and perhaps because of, this trusting relationship with God—Abram questions how he can know God’s promises will be fulfilled. God’s response once again is not to reprove or punish, but to recommit to Abram in a ritualized covenantal ceremony, speaking to Abram in a language he would understand.

Here, and in later chapters, we see a God who is relational—a God who can be talked to, questioned, negotiated with, and argued with. We see a God who wants to be in committed relationship with humanity, a God willingly and actively bound to another person in a covenant relationship. Notable to me is that in this relationship, God goes first; the only thing required of Abram at this point is willingness and trust. We might see here a reflection of a principle taught in the First Epistle of John—“We love [God] because [God] first loved us.”

F. Hagar’s story (16)

Buried at the heart of this story about God and God’s promises is the story of Hagar, an Egyptian woman enslaved by Abram and his wife Sarai. “Hagar” apparently means “foreigner,” which I can’t imagine was the name her mother gave her. To me, this is the story of a woman who is so un-seen by those around her she is not even called by her own name; Sarai and Abram consistently refer to her as “your/my slave,” not even using “Hagar.”

The text is ambiguous on whether or not Sarai offering Hagar to Abram to use to impregnate (and thus give them a child) is an act of faithlessness (not trusting God to fulfill God’s promise of giving Abram offspring, and thus taking matters into her own hands), or faithfulness (creative problem-solving and collaboration with God to bring God’s promises to pass). Whatever the case, when I, as a modern reader, slow down enough to actually think through Hagar’s experience here, I feel sick to my stomach.

And yet, this is the story we have. Is it possible to still find it instructive, and to find even the ambiguity of the text instructive? Without at all condoning Hagar’s enslavement or abuse at the hands of Abram and Sarai, I think the question of, When do we wait on the Lord, and when do we do all things that lie within our power? is a live and important one. I think the ambiguity preserved in the text on whether or not Sarai should have waited patiently for God and not tried to make God’s promises happen on her own timeline is valuable. Can I find that useful while still wholeheartedly believing it was wrong for Sarai and Abram to use another person in this way?

Hagar’s painful story continues as she becomes pregnant and Sarai’s jealousy and pain calcifies into abuse, and as Abram stands by and lets it happen. Eventually, a still-pregnant Hagar escapes her enslavers and runs into the wilderness. (Familiar Bible readers will again note the foreshadowing of the Exodus story, this time in reverse—an Egyptian, oppressed by Hebrews, escapes enslavement and will find God in the wilderness.)

The text that follows is both beautiful and challenging. The angel of the Lord finds Hagar in the wilderness, by a spring of water on the way home to Egypt. After asking her where she had come from and where she was going, the angel of the Lord tells her to return and “submit” to her enslaver. (Robert Alter translates this as, “Return to your mistress and suffer abuse at her hand.”) Again, this is stomach-turning. I hate the idea of God or God’s messenger telling a person to return to an abusive situation or to continue to suffer abuse.

Read as part of this larger narrative, and still holding my firm conviction that God would never condone or excuse abuse, I also see Hagar being invited to claim her place in God’s promises. The angel of the Lord repeatedly says to her that her seed will be multiplied “beyond all counting” (the same promise given to Abram), and reminds her of her son’s future. The angel tells her that her son will be named Ishmael, which means “God hears,” as a reminder that God has heard her suffering and is aware of the abuse she has suffered at Sarai and Abram’s hands.

Hagar then names God—the only person, man or woman, in the Hebrew Bible to do so—“El Roi,” which has been translated, “The God Who Sees,” or sometimes, “The God Who Sees Me.” She presumably then returns to Abram and Sarai where she “bore Abram a son,” whom Abram names Ishmael.

Again, the text leaves room for ambiguity. Is it possible that Hagar would have perished in the desert before reaching Egypt (a fate alluded to later on in Genesis 21), and to read words of the angel of the Lord as encouraging her to choose to live and have her baby, even in excruciatingly difficult circumstances?

I can imagine Sarai and Abram’s shock when Hagar, an escaped slave, returns to their household willingly. I am reminded of Jesus’s invitation to turn the other cheek, and of a reading which sees that not as a commandment to suffer further abuse, but to continuously assert your own dignity even in the face of violence. The text is silent on Sarai’s treatment of Hagar after her return; we don’t hear of Hagar again until after Isaac is weaned (Genesis 21).

Whatever the case, I am deeply moved that at the heart of Abraham’s story—the origin story of God’s chosen people—is this story of an oppressed, enslaved, abused, foreigner woman who was seen and known by God, and who asserts her own dignity and claims her place in God’s promised blessing for all people.

E. God reiterates promises; a covenant ceremony/ritual is performed; Abram (now Abraham) questions (17)

God again reiterates God’s promises to Abram, renaming him Abraham and this time including Sarai (renamed Sarah) in the promise of future offspring, specifically promising “a son by her.” (Previous progeny promises were made only to Abram.) God invites the newly-renamed Abraham to participate in a covenant ceremony, mirroring the ceremony God performed for Abram in Genesis 15 and offering a permanent, visual, visceral reminder of God’s (still unfulfilled!) promises to Abraham.

D. Abraham separated from and contrasted with his nephew Lot; Abraham rescues Lot; God’s promises to Abraham reiterated (18 & 19)

Again Abraham’s behavior (this time his hospitality) is held up as superior to Lot’s, and again his household is separated from Lot’s. Again Abraham acts in generosity and wisdom, while Lot is foolish, soon in danger, and needing to be rescued. (Notably, included in this depiction of Abraham as the model of righteousness is Abraham negotiating with and even questioning God.)

C. Sarah & Abraham in danger; God protects and delivers (20)

Again Abraham believes his life (and thus God’s promise of a son by Sarah) to be in danger and tells someone his wife Sarah is his sister. Again the text in Genesis is ambiguous on if he is lying or telling a half-truth, and on if this course of action is endorsed by God or not. Again Abraham’s choice puts Sarah (and specifically Sarah’s womb/sexuality) in danger, and again they are protected and delivered by God.

B. Abraham challenged to let go of his future family (Ishmael & Isaac); God’s promised blessings are reiterated (21 & 22)

The story of Abraham sending Ishmael and Hagar away into the desert and the story of the binding of Isaac are perhaps two of the most difficult stories to reckon with. I cannot reconcile a good and loving God with a God who would ask a parent to harm a child, even as a test, even to teach a lesson, even if the child is ultimately spared.

The God I believe in does not ask parents to kill their children, full stop. Not under any circumstances, not for any reason. But in literature, God might—and it might drive home an important larger point about God’s faithfulness and God’s deliverance. As the concluding theme in our chiastic pattern, these two stories together represent the greatest threat yet to God’s ability to keep God’s promises.

Without literally believing God would ask someone to contemplate or come close to harming their child, I can appreciate the literary parallel to the opening of Abraham’s story—being told to go forth (lek leka) from his family of origin and travel to a place God would show him, and then to go forth (lek leka, the only other time that specific Hebrew phrase is used in the text) and sacrifice his future family at a place God would show him.

It’s ambiguous in the text if Abraham is knowingly sending Ishmael and Hagar to their deaths in the desert, but given that he is an experienced desert traveler and he sends them away with only “bread and a skin of water,” it’s hard to imagine he didn’t at least consider the possibility. And when paired with the following chapter, where God explicitly tells Abraham to kill his other son, it seems that the literary intention is for us to make that connection.

What the reader sees (but Abraham does not) is that after being sacrificed and sent to their deaths by Abraham, an angel calls out from heaven and the Lord provides deliverance (a well of water) for Hagar and Ishmael. Are we meant to read Ishmael’s story onto Isaac’s and hope for deliverance for Abraham and Isaac as well?

It’s unclear in the story of the binding of Isaac what Abraham expects will happen—when he and Isaac part from their companions, he tells them “we will come back to you” (emphasis added) and tells his son, “God will provide the lamb” for the sacrifice. We’ve seen that Abraham has no problem lying when he feels he needs to, so that’s a possibility, but so is an abiding trust that God will deliver and protect them.

In any case, the text seems intentionally written to be heart-rending and horrifying, repeating words like “father” and “son” and slowing down the narration by including minute details as we approach the moment of sacrifice. We, like Abraham, might be holding out hope for deliverance, and, as the knife draws ever closer, wondering if we were mistaken—if deliverance might not come. I believe the reader is meant to feel the agony of this experience, which throws into even sharper relief God’s deliverance at the very last moment.

This is not an experience I ever want to feel comfortable with or hear a satisfying answer for. It should feel extreme. It should feel horrifying. I think its literary power depends on that.

At the same time, allowing the story to put Abraham’s children in danger is a powerful literary device that drives home the ultimate point that nothing can prevent God from keeping God’s promises—not even God. God is faithful, even when faithfulness seems impossible, and even when it seems like God is the very Being who has betrayed or abandoned us. To an ancient audience acquainted with death, displaced from their homes, feeling like there was no possible way God’s promises to them could be fulfilled, wondering if God had in fact forgotten or betrayed or abandoned them, I can imagine this being an incredibly powerful reminder.

And so I don’t read this as much as a story about Abraham’s faithfulness to God as I do a story about God’s faithfulness to Abraham, and so to all of us. Even when it appears that God (or that following God) is the very source of our troubles and distress, God is faithful and God will deliver.

Pairing these stories and putting them as the final element in this chiastic structure reiterates that God keeps God’s promises even when it seems impossible, that God delivers, and that God provides. Whether it’s water in the desert for Hagar and Ishmael or a ram in the thicket for Abraham and Isaac, God provides.

A. Epilogue/Genealogy (22:20–24)

This section concludes just as it began, with a genealogy of Abraham’s family.

Is this a perfectly satisfying resolution for me? Honestly, no. Yes, this literary analysis is helpful; it reveals that at the heart of the story is Hagar, reminding us again and again that God sees, God hears, and God delivers—even as Abraham is invited to trust in God’s promises when they feel delayed, threatened, or impossible. In service of these truths about God, the text may portray God doing literarily what God would never do literally.

Even so, I still have many questions—but I appreciate the invitation to wrestle. Perhaps that wrestling is part of the story’s power: Thousands of years later, we continue to debate what this narrative means about God, the world, and our place within it. What does it mean that the identity-forming story of the Abrahamic people centers such profound human distress and moral perplexity that it has generated argument, struggle, and interpretation for millennia? Perhaps we are not meant to arrive at a neat resolution.

Abraham’s story ultimately reveals a faithful, relational God—one who can be questioned, argued with, negotiated with, and even persuaded. If that is so, then perhaps the unresolved tension of the story is not a failure of meaning but its deepest invitation. The wrestle, after all, may be the point.

Cece Proffit is the social media editor for Wayfare and lives with her family in Iowa.

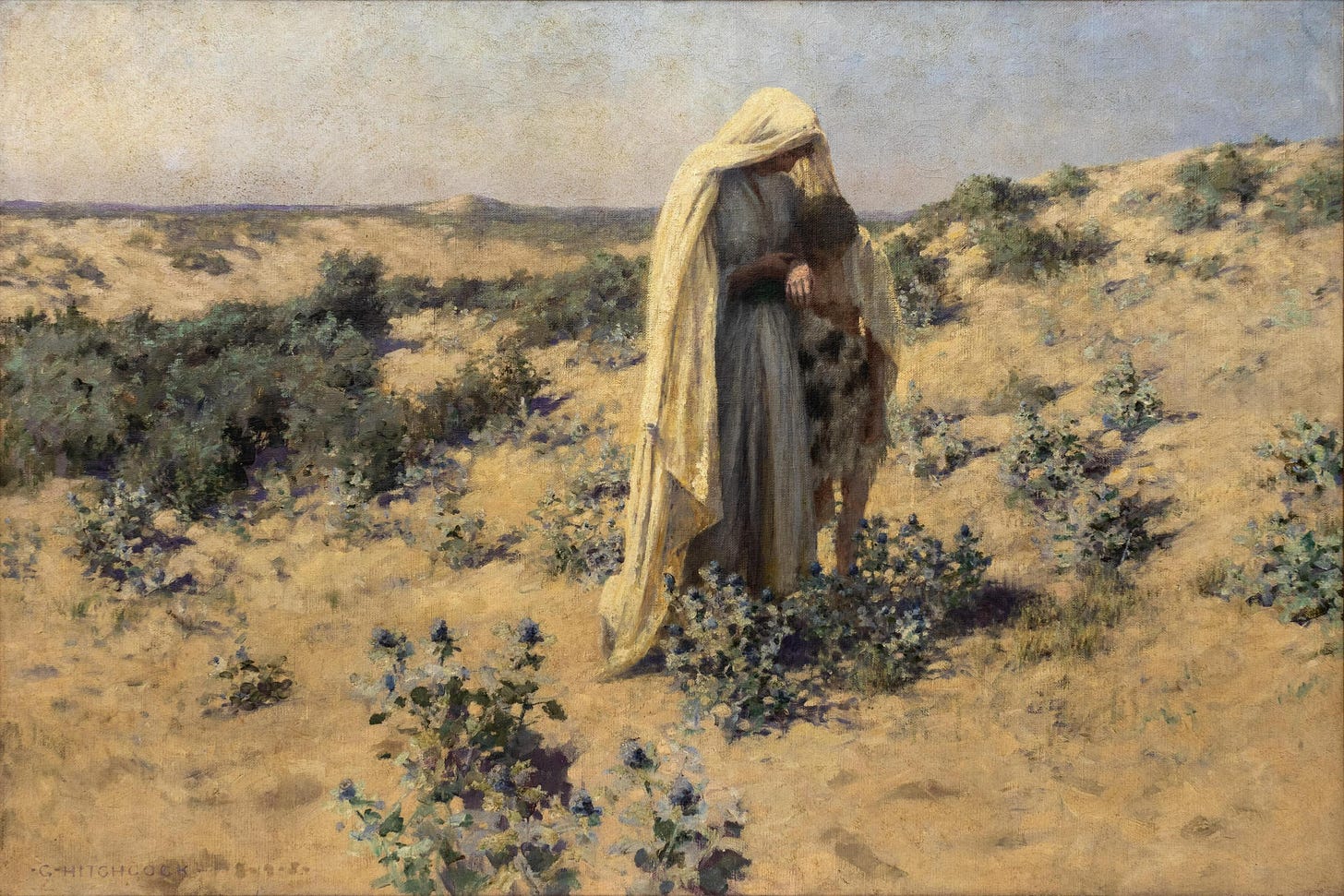

Art by Jean-Charles Cazin (1840–1901), Hubert von Herkomer (1849–1914), George Hitchcock (1850–1913), Carel Fabritius (1622–1654), and Emanuel Krescenc Liška (1852–1903).