One of the most bloodstained debates in Christian history was over the relationship of Jesus Christ to God the Father. Was he fully equal? Subordinate? Made by God or co-eternal with God? The Nicene creed (AD 325) declared the full equality, the “consubstantiality,” of Father and Son—but the questions continued to be violently contested for many decades to come, especially in the Eastern empire. Much more was at stake in the debates than the abstract question of divine equality. Perhaps most critical for believers was (and is) the question, was the Incarnation of Jesus Christ—a being who suffered and wept, who both craved and knew love and friendship—a temporary setting aside of divinity, or the fullest possible revelation of that divinity?

In historic Christianity, it is most often believed that “the king ‘empties’ himself, becoming a servant only for the duration of Jesus’ brief ministry and the sacrifice of the cross, but his true being is as almighty king.” Others have seen the life and ministry of Jesus as an absolutely accurate reflection of the fullness of the Father. No question has greater impact on how we understand the nature of God. And Christian history reveals no consensus on the answer to that question.

Early Christians, almost without exception, saw Jesus as subordinate to the Father. They also proclaimed that Jesus brought an astonishing new understanding of God. Before the love made concrete and effable in Jesus, mused a first-century convert, “what men had any inkling of who God is?” Ignatius and Irenaeus made similar declarations. Maximus the Confessor agreed some centuries later: “through his flesh he made manifest to men the Father whom they did not know.” Jesus’ life of compassion, non-violence, forgiveness, and selfless sacrifice created radically new ways of thinking about God’s power and dominion. For early Saints, forgiveness, mercy, selflessness, humility—these were not temporary expedients for surviving in a hostile Roman empire; they were the authentic way of emulating and acquiring “the divine nature.” Jesus was not just showing the way; he was the way.

But human constructions of power and justice and authority and kingship have persistently pushed against Jesus’s revolutionary gospel. Human passion for fairness and retribution, for validation and vindication, have often led Christians to see Jesus’s repudiation of the crown in favor of the manger, his refusal of sovereignty in favor of loving service, as a mere ploy, a role he temporarily assumed (this has become the doctrine of kenosis). Even devout Christians can sing hymns that anticipate with sacred Schadenfreude a return in triumph of him who first came in humility, perhaps forgetting that his conquest of death and sin through love was his triumph.

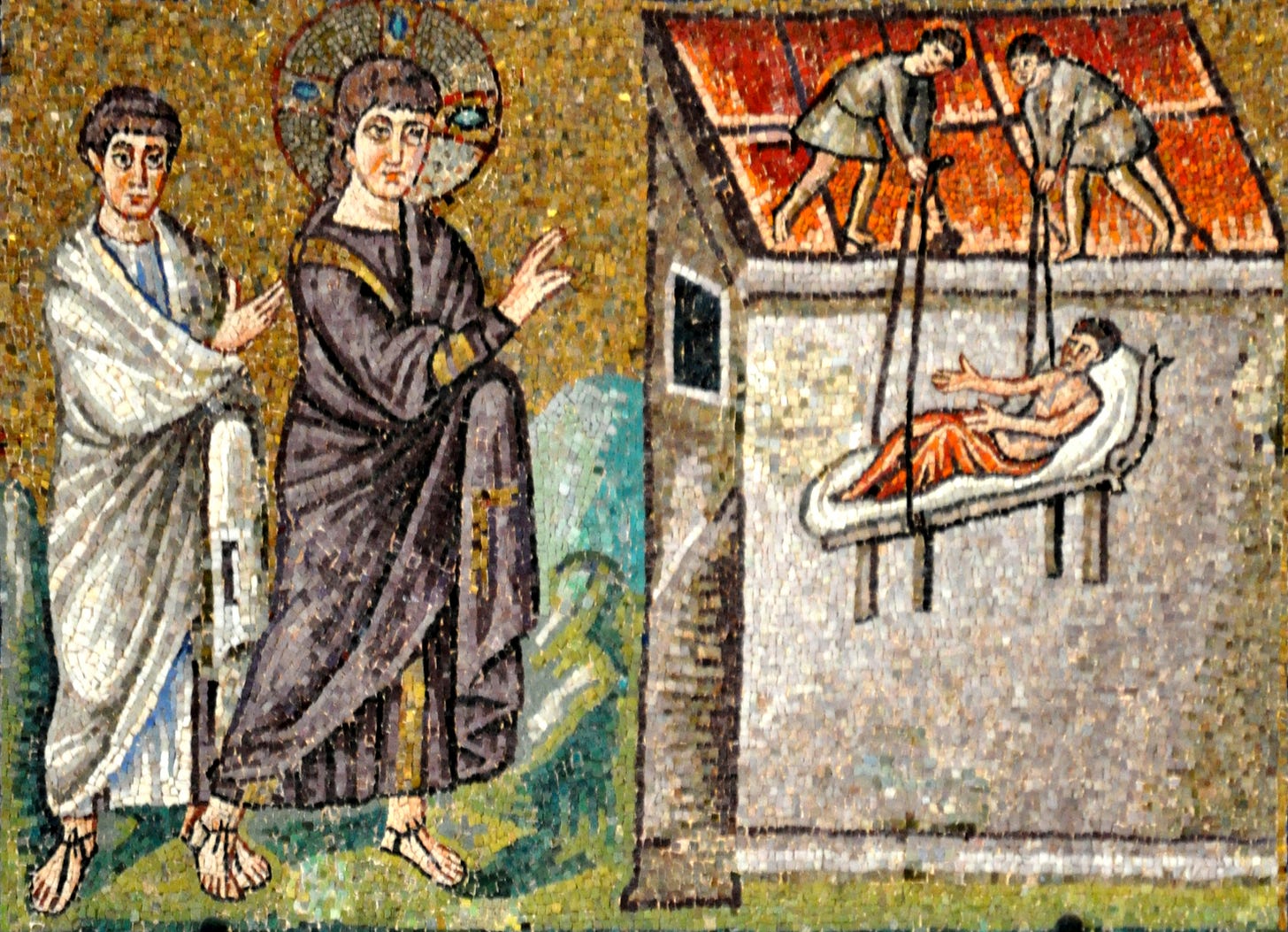

A church in Ravenna marvelously but tragically bears witness to the church’s insistence that God embodies all those trappings of power and prestige from which Jesus tried to wean us. In the early sixth century, Arian Christians in Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo created some of the most stunning mosaics to survive in the modern world. Jesus is depicted through the various stages of his life: as a beardless youth healing the sick and raising Lazarus; a more mature Jesus sups with his disciples and is betrayed by Judas.

A few decades later, conquering Nicaean Christians removed some mosaics and added their own: an enthroned Christ in majesty. Elsewhere in Ravenna images of Christ in a soldier’s garb appear. The figure of Christ Pantocrator—Christ the All-Powerful-- becomes pervasive in church art. Gradually, systematically, increasingly, Jesus has been reinscribed in all those forms of power and status that his life bore witness against. A Jesus who washed his disciples’ feet and was persuaded to stay and sup with importuning friends seems increasingly remote—roles now subsumed by a truer identity celebrated in art and hymns, along with anticipation of his glory-shrouded return.

In recent decades, prominent voices have worked to rekindle astonishment at the Incarnation as itself the news that Jesus was the fullest revelation of God. Kierkegaard makes this point emphatically in his reading of Philippians: “This form of a servant is not something put on like the king’s plebian cloak, which just by flapping open would betray the king…—but it is his true form. For this is the boundlessness of true love, that in earnestness and in truth and not in jest it wills to be the equal of the beloved…. The presence of the god himself in human form—indeed in the lowly form of a servant—is precisely the teaching.”

What teaching? That God’s being and power and influence are a function of love, the love of a God who heals, sacrifices, and queries his friends earnestly if they love him in response. The teaching that absolute but effable love, acted out in concrete ways from Bethlehem to Calvary, as well as at the shore of Galilee and on the road to Emmaus, are the essence of God and his kingdom. No other power or dominion is worthy of God or his disciples. Christ’s incarnation was not strategic or instrumental. It was lived solidarity with his people and the fullest revelation of God the Father. Helen Oppenheimer has reminded us of this aspect of at one ment, by taking seriously the word’s etymology: “For God nonetheless to have the right to say, ‘behold, it is very good,’ God had to experience at first hand the sufferings of mortal creatures…. Could any promised heaven justify what creatures have to undergo? Unless the creator is Incarnate in this world, and not only tells us it is worthwhile but finds it worthwhile alongside us.”

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Mosaics from the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna.