It starts in the desert.

In the beginning of the world, says Genesis, the whole earth was a void and the spirit of God swept over it. This desert out on the banks of the Jordan is no void—even in the night the camels moan and the crickets chirp—but when it does get quiet some say you can still feel the spirit of God sweep by, breathe it deep down into your chest.

A long time ago, the prophet Amos looked out past his orchards and his flocks west of the river to the desert in the east and said There are days coming—yes, the vision must have fallen on him the way the sunset can make the desert suddenly cold—There are days coming says the Lord God when I’ll send a famine in the land. Not a hunger for bread or a thirst for water, but for words of the Lord. And the ground itself will grow parched and cracked with your deafness and my absence.

There are days coming, said the prophet, when men will wander from sea to sea, from the north to the east: they’ll run back and forth, looking for a word from me.

But they won’t find it.

It’ll be too dry, he said.

So John doesn’t wander from sea to sea. John doesn’t run this way or that. He walks straight into the river until it covers his head then out the other side where the dust gets mixed in his beard. He listens to the camels moan and the crickets chirp, and then to the silence.

The dead prophet Amos smiles. It starts to rain.

All through Judea, they hear about it. About the wild man who eats wild honey and speaks wild words that are at once sharp and sweet. All through Judea, after the sun sets but while the last cooking embers still glow, people talk about this lightning in the desert, the way a flash of it can set your life into such stark relief.

The farmers talk about John, wonder about sending their sons to see him—ask themselves if they’d ever come back. The merchants talk about him, wonder what they could buy from some Bedouin to justify making the trip. The contractors and the taxmen talk about him, of this man who earns nothing and builds nothing but knows everything, maybe, that a man truly needs to know. The students and the scholars talk about him, at once drawn to and disturbed by the rumors of a living human being who speaks as if the word of the Lord is a fire shut up in his bones.

Even the soldiers stop telling stories of far-away, half-forgotten homes and of the bloody fields and dead companions who stand between them and those old memories. When the sun sets in the west, even the soldiers look east and talk about whether it’s true that there’s someone there who can teach you how to start a new and clean life, who can make you feel light again.

But the slum-dwellers of Jerusalem, packed tight into the Temple’s shadow, they talk about him most of all because of whispers that make their hairs stand on end, whispers that John says the time they’ve been waiting for is coming—and if it is, it cannot come too soon. Yes, no time is too soon for the sun to turn dark and the moon into blood and a prince of legends to come and break this world apart.

And through all this talk, the embers cool and dim to ash. Mouths slow and then fall still, eyes wander through the shadows, minds grapple with the pressures of the coming day until, bested, they slink off into sleep.

In the morning, farmers will rise again to their fields, merchants will examine their wares, scholars will take up their scrolls while soldiers take up their weapons and patrol the streets, slum-dwellers will wake to their slums—tomorrow will look so much like today as to make the two, once they are yesterdays, virtually indistinguishable.

Except to those few who wake up with last night’s cooking embers still on their minds. Who feel the new day’s sun rise in the east and eagerly turn their faces to it, who take the roads up through the hills and who quicken their pace when they see the river moving—as if pulled by the same irresistible force that has drawn them away from their day’s labors and toward the desert, toward the wild man whose words divide darkness from light. For those who trace back the route over which evening tales have been told to its source, this day can never be like any other.

When John speaks, the words of dead prophets come back to life. This is the first resurrection.

Repent! says John. For every valley will be made high and every mountain will be made low; the crooked will be made straight and the rough places smooth. And the glory of the Lord will be revealed so that every living thing will see it at once: the mouth of the Lord has spoken it.

Repent! says John. Because the day is coming when the proud will be burned down to stubble, when the wheat is gathered out from the chaff.

Repent! says John. Because the time has come when the kingdom of God will smash the kingdoms of the earth to pieces.

Yes: Repent, says John, because your soul has come home to the wilderness, and now it’s time to teach your life in the city the things your soul knows.

Then John walks into the river, and you can see the shape he cuts downstream in the current. And that shape is a knife which cuts your heart open, so that by the time you reach the water you’re aching to give up all the wrong things you’ve done. And you tell him: “I can’t go on this way,” and he says: “you don’t have to,” so you say: “but how?” and he looks at you hard, so hard you see your life with new eyes, and when he tells you what you have to do, you’re ready to make your decision: to walk away now, forever, and staunch the bleeding with an old rag until you can harden your heart, or to step forward, cut your own shape into the current, then lose yourself for a moment beneath the water, immerse yourself in a covenant it is no small matter to break.

And if you take that path, if you go under and then rise from the water for a new breath of desert air, if you walk up out of the river feeling clean and light, if you sit up on the bank watching the baptisms go by until John steps out of the river again, he’ll tell you: “This isn’t all. He’s coming. And you’ll be baptized in fire before the End.”

Committed to the scriptures as he is, John still makes the scholars nervous. They ask him why he does what he does, and when he answers and the words ring through their bodies, they still ask him to point out where exactly in the text he gets this or that idea, who exactly in the text he thinks he is. They question him as if in search of a scriptural diagnosis: is he the Messiah? “No,” he says. Is he Elijah? “No,” he says. Is he the prophet Moses mentioned when he recited the law before all Israel the second time? “No,” he tells them, “no.” Then they throw their hands up and wonder, but don’t dare to ask, whether he isn’t in fact simply a devil-possessed madman, whether that’s why he wears strange clothes and eats strange foods and dwells—of all places!—in this desert.

Maybe it’s an inevitable conflict between revelation and education: though each always wants to give the other its due, neither is quite ready to acknowledge the other as supreme, lest its own integrity be lost in the process.

So the scholars and their students decide it won’t be possible to guess whether John was a prophet or a lunatic until long after he’s dead—and that as a matter of principle, it’s dangerous to believe in a prophet who is still alive and may therefore easily yet prove to be a false one. It’s far better, the scholars tell their students, to wait for death to seal a prophet’s message and actions and for generations to pass so that consensus can emerge.

That’s when John compares them to desert snakes, who seek out the sun in the heat of the day and bask in it a while, but hide beneath the earth when evening comes and it turns cold.

The scholars explain gently that they are carrying on a grand tradition with an extensive intellectual (not to mention literal) genealogy with which John is no doubt familiar, and that they deserve a certain degree of respect.

John points to the rocks where the snakes love to lie and tells them that if it were necessary, their work could be done by those rocks.

“Why do you talk like that?” say the scholars. “Who gave you the right?”

“Why did you come here?” John says. “Who warned you of the wrath to come?”

He arrives as dawn is giving way to morning.

“Why are you here?” says John to Jesus.

“I want you to baptize me,” says Jesus to John.

“So soon? I’m not ready,” says John.

“But it’s time now. I’m sure of it,” says Jesus.

John looks at him. The long, deep look John is known for.

“Are you him? Are you the one?” says John.

“I think so,” says Jesus, and they’re quiet a while.

“And it’s time?” John says.

Jesus nods.

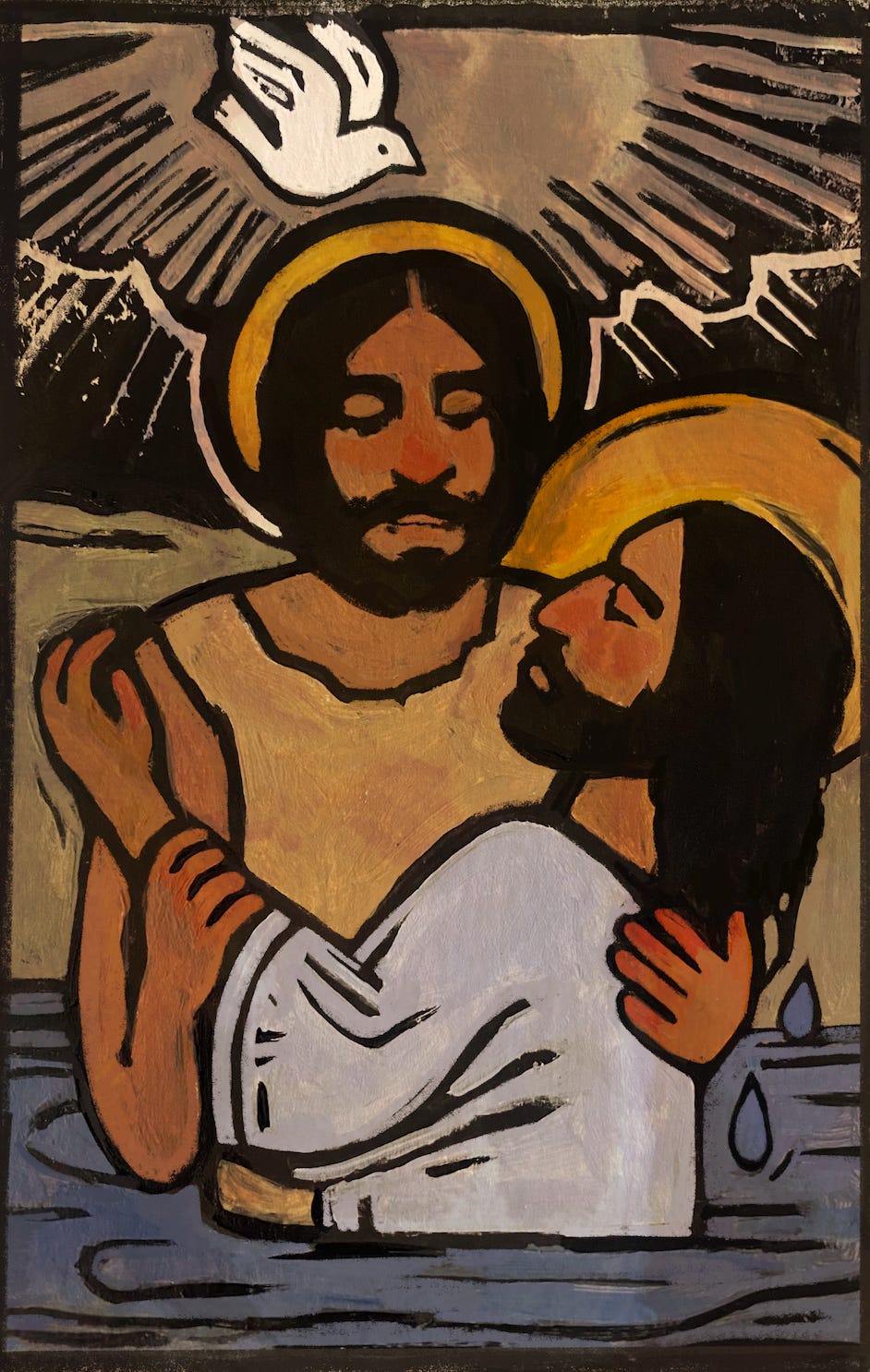

They walk down into the river, which is a bit chilly still so early in the morning, though neither complains. John buries Jesus’ face under the dirt-brown of the river water, then brings him back up into the daylight.

And all at once, the sky is bigger and the sun is brighter and there’s no room left in this moment for doubt.

A bird swoops down to skim the surface of the water for insects, then rises. Strange that at a time like this anyone should notice that.

Strange that although within a month John is in prison and Jesus is deep in the desert, anyone should remember it.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Original artwork by Sarah Hawkes.

This is just so beautiful