“If his offering be a burnt sacrifice of the herd, let him offer a male without blemish: he shall offer it of his own voluntary will at the door of the tabernacle of the congregation before the Lord. . .”

Someday they’ll see: the driving wind mingles the dust of my body with the ashes of the moth —Sauda

Ages ago, longer ago than anyone can remember, they say the Israelites spent a last night as slaves in Egypt. They packed up their bags, borrowed their neighbors’ jewelry, spread lambs’ blood on the doorposts, and waited for God’s judgment to fall on their oppressors. When it was done—and before any mob came looking from blood-marked door to blood-marked door for revenge—the Israelites got up, and they walked away and away and away for the next forty years.

Every Jew in Galilee knows this story by heart, because each year, just as the cool months give way to spring, thousands and thousands of people pack their bags, borrow a little money from their neighbors with promises to bring back something from the south, and take to the roads toward the Temple in Jerusalem, where the lambs today are slain. And whether they have been on the trip themselves yet or not, every Jewish child in Galilee has heard of the endless crowds there, about how it looks from a distance like all Israel has moved out to tents in the hills and the desert once again.

In the southern parts of Galilee, children will shirk chores and perch on roofs or in trees to watch the travelers pass by. And is it only pilgrims’ clothes they hear rustling below or also their ancestors’? Does the smell of sweat come from a long day of walking in the heat or from years spent as slaves in Egypt? When the children sit above the road, they feel time collapsing beneath them.

On the road this year, Salome feels like space is also collapsing: she asks a question to one of Jesus’ followers from the marshes upriver and gets an answer from another whose home is near Magdala, west of the lake. She hears about her sons from a woman on her left who comes from the foothills of Mount Hermon and a girl on her right who met James and John near Mount Tabor. On this road, she meets the wives of some of the seventy men Jesus called and blessed and the mothers of other people he healed. On this road, it seems, a sweet sampling of the fruits of her sons’ and their Master’s ministry has been gathered.

“If only my sons could be here!” she thinks. And she wonders where they are now and how long it might be until she sees them again. She worries about them as she walks, and she worries about them more when she sees the soldiers by the roadside scanning the crowds at the southern edge of Galilee.

Not long after the soldiers are out of sight, a group of men with faces wrapped tight against the dust walk up beside her. Salome quickens her step to move away from them and keeps her eyes focused ahead, but the men match her pace and stay close. When one of them takes hold of her arm she pulls it away and shouts out a threat—but then he unwraps his face.

“Please don’t hurt me,” says James. “I forgot how you feel about surprises.”

She doesn’t know whether to scold him or hug him, so she just laughs. John and Peter and Jesus and the others unwrap their faces and laugh with her.

She shouldn’t be surprised that they’re here. After all, time and space fall apart so easily on the journey south for Passover.

*

Though Jesus’ followers from Galilee are excited to see him, there’s no sign anyone else is waiting until the second evening of the journey at a village where the Jabbok flows into the Jordan. Men who were once John’s disciples scan the passing travelers, shout greetings to Judas and Andrew, then rush down and hoist Jesus up on their shoulders like a groom, singing and clapping as they carry him off to a feast.

They’ve prepared for him well. After dinner, the half of the village that isn’t busy providing accommodations for travelers gathers to listen to the man who might be heir to John the Prophet’s legacy and to savor his strange stories.

He tells them about a woman who loses the precious silver coin that was her whole dowry. Then he asks them: won’t she light a lamp after dark so she can sweep every last corner of the house, not sleeping until she finds it? And when she finds it, won’t she celebrate with her friends?

He tells them another story: a man’s younger son asks for his portion of the inheritance, sells it for silver, then moves away to a Gentile city and wastes the money breaking every commandment he knows. His sins alone are enough to keep rain from falling over the whole region for a year, and a terrible famine strikes the land.

The young man begs his friends for help and mercy, but their goodwill has gone the way of his wealth. Only one of them offers anything: a position feeding pigs that pays so poorly, soon the young man envies his charges their slop.

Hunger and guilt gnaw at him until one day he comes to himself. “In my father’s house, even the servants have enough bread,” he thinks. “Why should I die here of hunger?” So he leaves the pigs and starts toward his old home.

On the road home, he thinks: my father taught me the right way to go in life, but I left him for the vanity of the world. He thinks: if I were my father’s son, I’d have lived the way he taught me—I’m no one’s son now, maybe I never was. If I could serve my father for seven lifetimes, he thinks, I’d still be in his debt. But he stays on the road to his father’s house, and he practices what he’ll say so that his tongue will know how to go on after his heart breaks at the first sight of his father’s stricken face. He practices so that he’ll be able to plead for work with his father, whose face was a mirror that showed only the truth long before the truth was such a sharp knife.

But all his practice is for nothing. Before he ever gets home his father runs out, holds him tight like a child, and kisses his neck. The young man says, “Father, I’ve sinned against you and heaven!” But the father says, “You’re home, now. You’re finally home.”

The young man says, “I had my chance. I don’t deserve another.” But the father says, “Bring the ring his mother left him. Bring him shoes and a many-colored robe.” The father tells his servants to kill a fatted calf and throw a feast to celebrate. Then he smiles like he hasn’t in years and even laughs.

The older son, working in the fields, hears people in the distance start to sing and dance. He comes close to the house and smells the tender meat. “What is this?” he says to a servant, and the servant tells him how his brother has come home, and how his father has welcomed him.

“How is that possible?” says the older son, but the servant can’t answer so the brother stays outside until his father comes to see what’s wrong. “I’ve given up everything else I could have followed, everything else I could have had, for you,” says the older son. “I’ve gone wherever you asked me to go and worked long hours every time we’ve sown seeds and every time we’ve harvested. And yet we’ve never eaten even a goat’s kid in my honor—why have you given the son who abandoned you a calf?”

“You’ve had all this time with me,” says the father, “and everything I have is yours. So why shouldn’t we celebrate with the one who wasted so many years? My son was dead, and is alive again. He was lost, and now he’s found.”

*

After he finishes the stories, three scholars approach Jesus.

“You tell very interesting stories,” says the first.

“And your reputation as a holy person proceeds you,” says the second.

“Although reputations can be hard to live up to,” says the third.

“What can I do for you?” asks Jesus.

“Our young patron couldn’t be here tonight, but he’s expressed an interest in helping support you,” says the first. “Financially.”

“It’s our responsibility to advise him,” says the second. “We have no doubt that you’re a righteous man and that the honor you’re given as a healer is deserved, but we don’t know for sure—if you’ll forgive me for saying so—whether your wisdom goes deeper than homilies and simple tales.”

“What deeper wisdom are you looking for?” asks Jesus.

“We’d like to hear your opinions on some legal issues,” says the first. “For instance, there’s a woman from near here who recently returned home after spending several years abroad. She claims that her husband died, but can’t provide any proof or documentation. She expects his brothers to give her the share of the inheritance allotted to her by the marriage contract, but since there’s no proof her husband is dead, should that property be considered hers or held back for now?”

“I don’t get involved in property disputes,” says Jesus. “But remind them what the scriptures say: Wait for the Lord, and keep his way, and he’ll honor you with an inheritance in the land: when the wicked are cut off, you’ll witness it. If she’s broken the commandment and given false witness, she’ll find herself without an inheritance on the Day of Judgment. If the brothers break the commandment and covet, they’ll find themselves cut off. Tell them, and see if they can resolve the matter on their own.”

“What’s the use of law,” says the second scholar, “if every man does what is right in his own eyes? How can you expect them to resolve the issue without a judgment? After all, the property is only one of the concerns. The woman is childless, so if her husband really is dead, she has a right to one of his brothers. The nearest brother says he’d be happy to act as goel and marry her, but what if she’s lying and her husband—his brother—reappears? A correct ruling could protect the family from serious harm: what do you advise them to do?”

But Jesus just shakes his head. “I advise them to keep the matter away from the courts,” he says. “In the courts, a woman isn’t accepted as a witness. But when Ruth went to straight to her kinsman Boaz, he believed everything she said.”

The third scholar bursts out laughing. “You must be innocent indeed if you believe every woman is as virtuous and trustworthy as Ruth! If that’s what the brother expects, too, you’d better tell me your answer to a different legal question in advance: how much disappointment does a husband have to endure before he has sufficient grounds for divorce? How many burned meals does he have to eat?”

That’s when Jesus grows angry. “Moses gave laws of divorce to a stubborn and idol-loving people, but what was the only teaching on marriage Adam needed?” he says. “In the beginning, God created them male and female and said: Because of this, each man should leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and they should be one flesh.”

Jesus stares at the scholars a moment, then turns away.

“What God put together, men shouldn’t be teaching how to take apart,” he says to the villagers before he walks off.

*

In the morning, the scholars return the money their patron sent with them and tell him about their disappointing encounter with Jesus.

“He’s charismatic, but impractical,” says the first.

“He’s a careless thinker with a short temper,” says the second.

“It’s a dangerous combination,” says the third. “And when it gets him into trouble, you don’t want people to come asking you where he got his money from. That’s why we brought it back.”

But their young patron doesn’t let the matter rest at that, so the scholars have to retell the whole exchange, beginning from their first approach and ending with Jesus’ abrupt dismissal of the whole field of divorce law.

“I’d like to meet him myself,” says the rich young man. “Do you know where he stayed last night?”

*

Jesus leaves his hosts well before the young man reaches them, but all the pilgrims take the same route from here to Jericho, so the young man hurries to find them.

Since the crowds on the stone road move slowly, he runs through the dirt on the side. Dust covers his cloak, adds color to his thin young beard, sticks to the insides of his mouth and nose, but he keeps running. Pilgrims stop to laugh at the sight: since when does someone so well-dressed and wealthy travel alone with such disregard for dignity? But the young man keeps running. Though he’s not even sure how he’ll recognize him, he knows he must talk to Jesus.

The young man moves even further from the road to make his way around a big group of talkative Galileans, then notices there are also a number of Judeans in the mix. He slows down, scans the group, and recognizes a man from his village who was once a disciple of John.

The man next to that man, the one he’s listening to so carefully, must be Jesus.

The rich young man presses into the group until he can fall down at Jesus’ feet. And when Jesus stops, the whole world seems to stop with him.

“Master,” says the young man, “I know you don’t give rulings for any earthly court, but I want to know about the court of heaven.”

“Then why are you kneeling there?” says Jesus, “Stand up and walk with me.”

The young man does as he’s told. “Master,” he says again, “how can I inherit eternal life?”

Jesus laughs. “You’ve sponsored many scholars—I’m sure you know the laws about that inheritance. Have you killed anyone?”

“No,” says the young man, a little shocked at Jesus’ casual tone.

“Have you committed adultery?” asks Jesus.

“I’m not even married!” says the young man.

“Have you stolen?” asks Jesus.

“Of course not!” the young man says.

“Have you given false witness or cheated anyone in business?” Jesus asks.

“Never,” says the young man.

“Have you kept the commandment to honor your father and mother?” asks Jesus.

“As long as they lived, and I treasure their memory,” says the young man.

The stones feel strange beneath the rich man’s sandals: he’s far more used to riding on these country roads.

“If you want eternal life,” says Jesus, “you’re on the right path.”

The young man walks beside Jesus a while. Can it really be as simple as that?

“Is that all you need to do to get into the kingdom of God?” the young man asks.

Jesus glances at him sideways. “You didn’t mention the kingdom of God before,” says Jesus. “For that, there’s only one thing: give up everything you have and follow me.”

The rich young man almost trips on a loose stone. He was his parents’ only child. From his mother’s side, he has farmland he rents out in four different villages. From his father’s side, he has a successful business with agents in ten different towns. “What do you mean, give up everything?” he says.

“Sell it all,” says Jesus. “And give the money to the poor. Exchange every treasure on earth for one in heaven, where it can’t get lost or keep you up all night with worry. Follow me: sacrifice everything.”

Only once before has the rich young man felt this way. When his parents died, grief almost swallowed him, until he saw himself giving to scholars in a dream and woke up with new purpose in life. Why shouldn’t he move the rest of his wealth to heaven? When Jesus’ road lies before him, what use are the treasures of this world?

But there’s another thing the young man has to consider. Though he isn’t married now, some day he will be. Though the children he may have are only dreams now, some day they’ll be living bodies with physical needs. His mother’s fields aren’t his own: they belong also to her future grandchildren. His father’s business isn’t his own: it’s also a trust, an inheritance for hoped-for grandsons.

A weight like graves seems to rest on the young man’s chest. He knows Jesus is a holy man, and he wants to make the sacrifice Jesus asks for. He imagines himself letting go of everything but God’s favor, imagines himself giving away even the sandals he’s wearing so that the rocks cut his soft soles; though his feet bleed, surely something will bloom as he waters the desert with each step.

But he also imagines another life. He imagines a young woman, fair as the moon and clear as the sun, whose face is like the morning when he comes home to her at night. He imagines the pure daughters she’ll bear him, and the righteous sons: his parents’ grandchildren will grow to watch over their fields, manage their business, and he’ll teach them to give generously to both scholars and charities. He imagines himself respected as his hair grays, securing good marriages for his daughters and sons, giving counsel in time to their children. Telling his offspring’s offspring the stories of their ancestors.

There are tears on the rich young man’s face as he murmurs an apology to Jesus and leaves him. “Thank you for offering me one good life, but I choose the other,” he says.

And it will happen almost as he imagined it. He’ll find a moon-fair woman and marry her. After some time, she’ll bear him two daughters and a son. His fields and businesses will prosper; his children will grow and marry. His life will be sweet, if not always as good as he’d like—until, when his hair begins to gray, the people revolt against Rome but also turn on each other. The rebels will seize his fields and murder his daughters. The Romans will plunder his goods and raze his house and slaughter his wife and grandchildren and son.

For the rest of his life, he’ll stay up half the night, wandering through the darkness looking for them. Trying to find anyone whose death he might only have imagined. Who might have somehow hidden and escaped.

*

The apostles are astonished when the rich young man leaves Jesus. Not because they don’t understand why a good person would walk away from their Master, but because as Jesus and the rich young man talked, each of them felt a shadow of what he felt when Jesus first called him. Matthew remembers the way nothing else entered his mind in that moment, the way his body seemed to respond to the words before his thoughts did. Andrew remembers his feeling of discouragement being lifted away, as if by an invisible wind that lifted him from the lakeside to a hilltop. Peter remembers dropping the net, the thick ropes slipping so easily through his calloused hands, never to be taken up again. Even Simon remembers it: when there were so many reasons for him to leave as others did, he remembers thoughts of Jesus pulling him back like the current when you try to walk upstream.

“Why isn’t he coming?” asks Andrew, “Didn’t he feel that?”

“He must have,” says Jesus, “but it’s hard for a man with so many riches to join the kingdom of God.”

“It’s not that hard,” says Matthew, who regrets nothing.

Jesus glances at him. “You knew that money didn’t really belong to you, so you didn’t belong to it, either. But it’s hard for a man who trusts his wealth to come into the kingdom of God, harder than it is for a camel to pass through an opening the size of a needle’s eye.”

The apostles stare. Thomas looks for a puzzle in Jesus’ words, imagines the rich young man spending the rest of his life plucking out a camel’s hairs and passing them through a needle one at a time. The futility of the image exhausts him. “Is there any way, then, for a man like him to be saved?” Thomas asks.

Jesus looks around at all the twelve. “How many things have you seen God do that men can’t? With God, all things are possible. There will be joy yet in heaven over him.”

*

Peter knows he shouldn’t be bothered by this, but he is. He thinks of his wife and his mother-in-law, thinks of their faith and sacrifice. Why should a rich man with no family be excused for refusing to do something a poor fisherman has done? Peter knows he shouldn’t be bothered, but he can’t stop thinking about a story the prophet Nathan once told King David. A story about a rich man who spared sheep that were only things to him and killed a poor man’s only lamb instead, a lamb that was all the love and duty in the world to that man.

“We’ve left everything to follow you—” says Peter, but he stops before he can give voice to his complaint. A peaceful heart heals the body, he reminds himself, but envy rots the bones.

A breeze comes down off the hills toward the river, giving momentary relief from the lowland heat. Far ahead, Peter can almost see what must be Jericho’s city wall.

Jesus turns to Andrew. “How many homes have you stayed in since I called you to follow me?”

Andrew thinks. “A few dozen, at least.”

“And how many women cooked for you and cleaned up after you like you were their own sons?” asks Jesus.

Andrew smiles wide.

“How many people have you met who were like brothers and sisters to you?” asks Jesus, “How many houses would you be as glad to see again as your own home? How many fields do you love now as much as if you’d spent your whole life caring for them?”

Peter thinks not just of the villages, but of hills where he’s spent the night and risen with the sun in the morning. He thinks of drinking from the dew on the wild grass, of digging up plants with satiating bulbs. All of Galilee is his now. Galilee is his in a way no rich man will ever know.

“Whoever leaves a house or land or loved ones for me and my gospel is given hundreds of homes and lands and loved ones in this life. Your reward is coming already in this time,” says Jesus. “So there’s no need to be jealous of the lost who are brought back to life in the world to come.”

*

They reach Jericho at mid-day. In the winter, the warm, heavy air makes it a favorite retreat for royalty: Alexander the conqueror had an estate built here with plunder from his siege of Tyre; Mark Antony gave the whole city as a gift to Cleopatra at the height of their romance. After she committed suicide, the city reverted to the first Herod’s control. It was a pool in Jericho where that Herod ensured that the last heir of Judah Maccabee would spend the last moments of his life, lost beneath the water in an assassin’s arms.

The dates grown outside Jericho are sweet, and the spice trade from the east is good, but it’s still no wonder that many men left those comforts for the desert in the days when John preached there. Jericho is a city stained with too many old sins, too much old blood.

When John was in prison, most of his disciples hoped he would return alive, but from the day of his arrest the disciples in Jericho somehow knew their Master had been taken from them forever. When they finally heard the news of his death, they tore their clothes and fasted like everyone else—but theirs was pure mourning, without any surprise.

But they’re no longer mourning. They’re eager now to see the man who’s said to have a double portion of John’s spirit, and they have a feast ready when he comes.

When Jesus approaches the city, John’s disciples rush out and bow down before him. They bring him in to the meal, tell him he can eat as slowly as he likes and has no need to be afraid here, because there are already fifty strong men in this city who have committed to do whatever Jesus says.

“Should we send them to Jerusalem with you?” they ask as Jesus finishes his bread and starts tasting dates.

“There’s no need for that,” says Jesus.

“It’s no trouble. They want to help you,” they tell him.

“Do they know what I’m doing there?” asks Jesus.

“You don’t understand: they’ll do whatever you tell them to. If you say ‘go up to a mountain,’ they’ll go up. If you say, ‘come back to the valley,’ they’ll come back without ever having to know why,” say John’s disciples.

“What about when no one gives them orders?” asks Jesus. “When I’ve gone, will they look for me three days?”

John’s disciples keep pressing him until, washing his hands after the meal, he agrees to let the fifty come, but Jesus’ apostles hardly hear the rest of the conversation. Why is their Master talking about being gone?

*

Even the broad streets of Jericho swell almost to breaking with the mass of people who follow Jesus out of the city: his close followers, the extra Galilean pilgrims they’ve befriended, the fifty strong men from Jericho, and the hopeful disciples of a dead master.

From the city gate, blind old Bartimaeus hears them, unravels the threads of sound in his mind and recognizes the famous name of Jesus. Jesus, the healer. Jesus, the prophet. Jesus, who might be the promised anointed one.

He wishes he could be right in the middle of that cloud of sound, wishes he could make his way safely through the bruising elbows and crushing feet of the crowd to touch the man he’s heard so much about. Not that he needs Jesus to heal him as Jesus has healed so many others. No, Bartimaeus wants to touch Jesus so he will always remember in the most literal sense what it felt like when Jesus was there. He wants to touch Jesus so he can hold on to some connection to goodness on the days when the people are unkind and when the alms are few and when the loneliest place in the world is Jericho’s west gate.

But because there’s no way for a blind man to safely approach Jesus today, Bartimaeus decides to connect himself with the saint through a song instead. Yes, when the cloud of sound is pressing close, Bartimaeus sings from the bottom of his chest:

David, King of Israel!

David, King of Israel!

David, King of Israel lives forever!

And when the other beggars shout to him to be quiet, to make some room for their cries for charity to be heard, Bartimaeus only sings louder and deeper. Pours every memory from his lost sight into sound to celebrate the hero who, at any moment, may walk past.

Jesus stops. “Bring him to me,” Jesus says. “Bring the singer.”

So the crowd parts, and Bartimaeus drops his cloak in his eagerness to stumble forward and touch even the hem of Jesus’ robe.

“What can I do for you?” says Jesus.

“I just wanted to be near you,” says Bartimaeus. “It’s already enough.”

So Jesus takes the blind man’s hand and lifts it to his own face. Bartimaeus feels the warmth of tears there and begins to shake.

Jesus places Bartimaeus’s salty fingers gently on his blind eyes. The water returns at once to those dried-up eyes, and for the first time in years, Bartimaeus can see.

“It’s a steep road up to Jerusalem,” says Jesus. “I don’t want you to trip as you follow me there.”

*

On the road from Jericho up to Jerusalem, there’s no sign of blood in the Passover season. The robbers’ hands are clean, their nails transparent, the sleeves of each assassin spotless. Since the road is too crowded at this time of year for an ambush, they’ve washed their hands and wiped off their knives, and they’ve changed into merchants’ robes to sell the wares of the last year’s victims to the pilgrims who pass by.

In the coming days, wine cups across Jerusalem will serve as monuments for the spilled blood of Pharaoh’s Egypt. In the Temple, they’ll slaughter a flawless lamb in the name of God, filling hundreds of thousands of worshippers with reverent awe. But in this season of memory, the blood of the road’s victims lies forgotten, dried black and mixed with the dust beneath the feet of that man who buys a new coat, that woman whose eyes shine with delight at the bargain she’s being offered.

Since Bartimaeus’s eyes have been opened, he sees blood everywhere.

He turns to Jesus. “What does it mean?” he asks.

“The time is coming when everything that’s been covered will be revealed, and no secret will be hidden,” whispers Jesus.

A few steps back, Judas is walking carefully. He can’t see the blood like Bartimaeus, but he still knows it’s there. The closer he comes to home, the more he’s aware of hidden blood, of unspoken secrets.

Judas looks from the carefully washed hands of one robber to the clean fingernails of the next. Though he’s sure he’s awake, though he’d swear by heaven and by earth that one foot keeps moving in front of the other, Judas starts having his nightmare. His sister is carrying the water. Someone sees her: maybe it’s a robber, or a soldier. Maybe it’s someone she knows, someone she trusts.

After he’s raped her, the man walks away. He must wash his hands before too long.

The world forgets her invisible blood. The world never noticed.

*

They reach a village outside Jerusalem in the evening. It’s nice here, nothing like the Jerusalem Judas knows. Pilgrims sit under the shade of trees on the hillside to plan the last part of their journeys while Simon goes out to make arrangements for the next day with some of his friends. Goats bleat contentedly as they graze in the distance, and Jesus gives Andrew and Thomas instructions on where to go in the morning to get him a young donkey that’s never been ridden.

Before nightfall, the twelve settle into the house where they’ll be staying. Though everyone’s excited to be so close to the holy city at last, the long climb has left their legs sore and their lungs exhausted. Soon everyone but Judas is asleep.

Judas is too tired to sleep tonight, too tired to pray. But he’s almost drifted off at last when the angel appears beside him again.

“How long?” he says to the angel. “How long until this ends and all the nightmares go away?”

“I don’t know,” says the angel. “There are legions of us waiting for the sign, but. . .”

“But what?” asks Judas.

“Only God knows when the time is,” says the angel. “But many say it’s not close like we thought.”

“It has to be close,” says Judas. “The one we’ve waited for is here, on earth, already.”

The angel shrugs. “Maybe he doesn’t have to finish it,” he says. “Maybe things don’t look ready yet, and he’ll leave for now, and let them go on.”

“No!” says Judas. “He can’t.”

“I don’t know,” says the angel. “All I know is that there are legions of us, just waiting for the signal, but it hasn’t come.” The angel rises. “And maybe it isn’t coming.”

When Judas looks over again, the angel is gone. The angel is gone, and it’s a dark, dark night.

*

In the morning, everything happens for Andrew and Thomas exactly the way Jesus told them it would. They go into the next village and find the place where the road splits—sure enough, the animal is tied by the door there, nibbling on a vine. The next part feels so much like stealing it’s hard for them to do, but they follow Jesus’ instructions and untie the young donkey. As they start to lead it away, a man rushes out of the house after them yelling, asking what they think they’re doing.

“The Master needs your donkey,” say Thomas and Andrew, though coming out of their mouths instead of Jesus’, it sounds like a poor excuse.

But the man seems to recognize the words somehow. “Of course,” he says. “Go ahead.”

The donkey is surprisingly cooperative, considering it’s a donkey, and it doesn’t take them long to get back to Jesus and the growing crowd at the house. The pilgrims are back and the men from Jericho are back, so it’s difficult to get the donkey all the way to their Master in the courtyard, but they forget the inconvenience when they reach him.

Jesus’ eyes shine today, as if he can see something they can’t. As if there’s something of untold worth and beauty right ahead, and he’s irresistibly drawn to it.

They want to take him there, to help him get wherever he’s going.

Without quite realizing what he’s doing, Thomas takes the robe off his back and lays it across the donkey as a cushion for Jesus, and most of the twelve quickly do the same.

And after months of watching him walk, the apostles finally see Jesus ride.

Fill yourselves with joy, daughters of Zion! thinks Andrew, Shout your joy, Jerusalem’s daughters! See how your king comes to you: in righteousness, bearing victory. See how he comes: humble, and riding on a donkey’s foal.

But as they start toward Jerusalem, Judas remembers the angel and worries: why is Jesus riding a donkey like a king who comes in peace, instead of a horse like a king who goes to war?

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

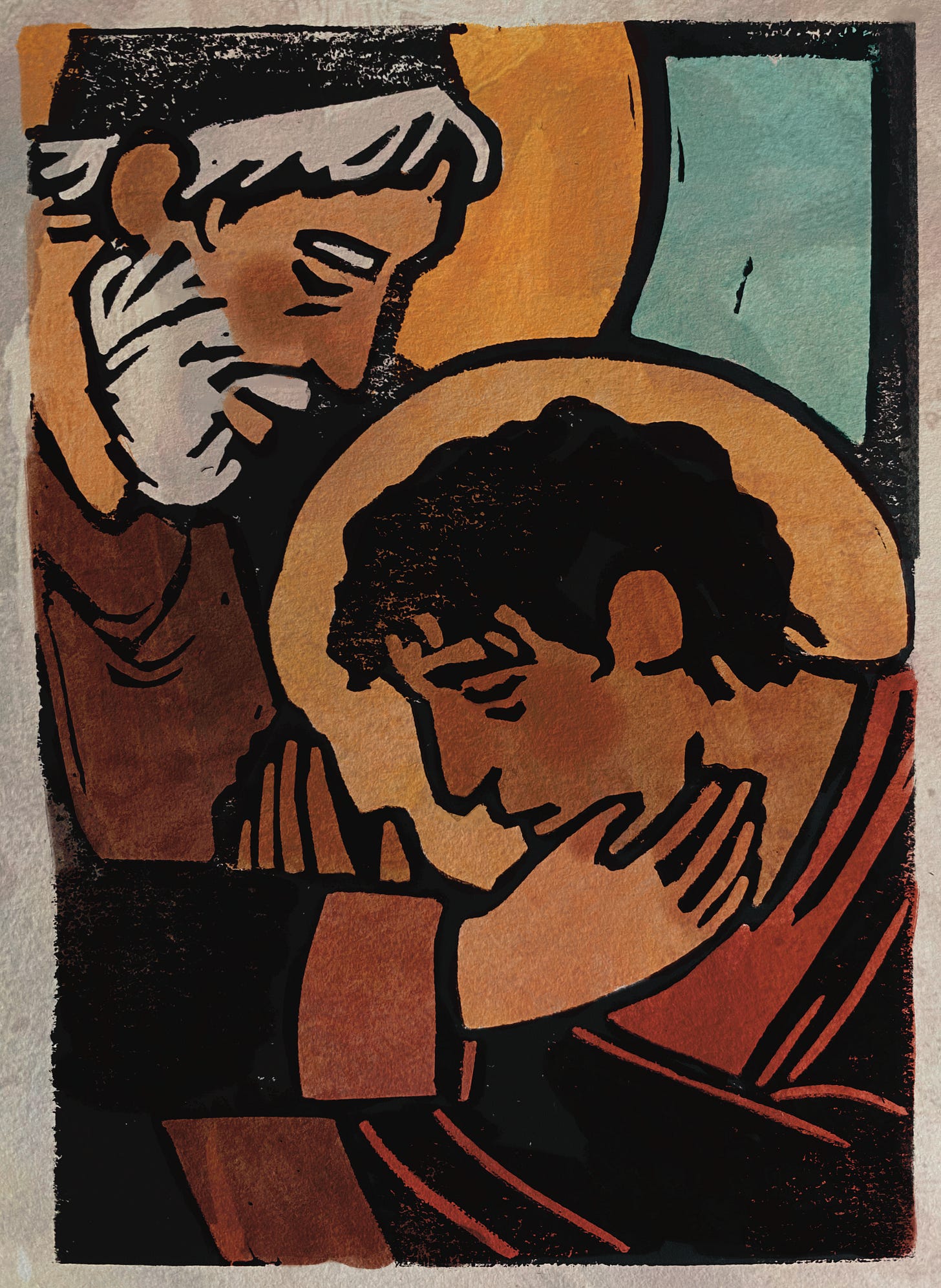

Original artwork by Sarah Hawkes.

To receive each new chapter of The Five Books of Jesus by email, first make sure to subscribe, then click here and select "The Five Books of Jesus."