“I am like a candle that has gone out on the grave of a poor man.”—Ghalib

Torches shine like scars on the dark, smooth face of this spring night when the clanking of steel against a rock startles eight of the apostles awake. A group of armed men—the high priest’s Temple guards and a few Roman soldiers—pass close by, muscles tensed in anxious anticipation.

Thomas and Andrew reach for the swords, only to remember giving them to Peter and James before they fell asleep, though now they can’t see Peter and James anywhere. Nathanael starts to ask what’s going on, but Simon covers his mouth tightly and pulls him further away from the search party’s torchlight.

“We need to get Jesus away from here,” Simon whispers. “Where did he go?” Matthew whispers back.

The eight look as far as they can without moving and don’t see any sign of their Master at all. The men with the torches slow down and start fanning out.

“What do we do now?” whispers Philip.

“If they get any closer, we run,” Simon whispers back. The torches get closer. Eight apostles rush to escape.

*

Peter shakes James and John when he hears men running. Torchlight is scattered across the garden now. Something is wrong. Jesus is slumped down against the trunk of a nearby olive tree. As soon as they see him, the three apostles hurry over to his side, but John trips over a root on the way and falls hard.

Several men shout in the distance about the noise and the torches start moving in Jesus’ direction.

“Let’s go!” says Peter, but Jesus doesn’t even try to stand up. John pulls himself up as the lights start closing in. As the men come closer, first their weapons, then their faces become visible.

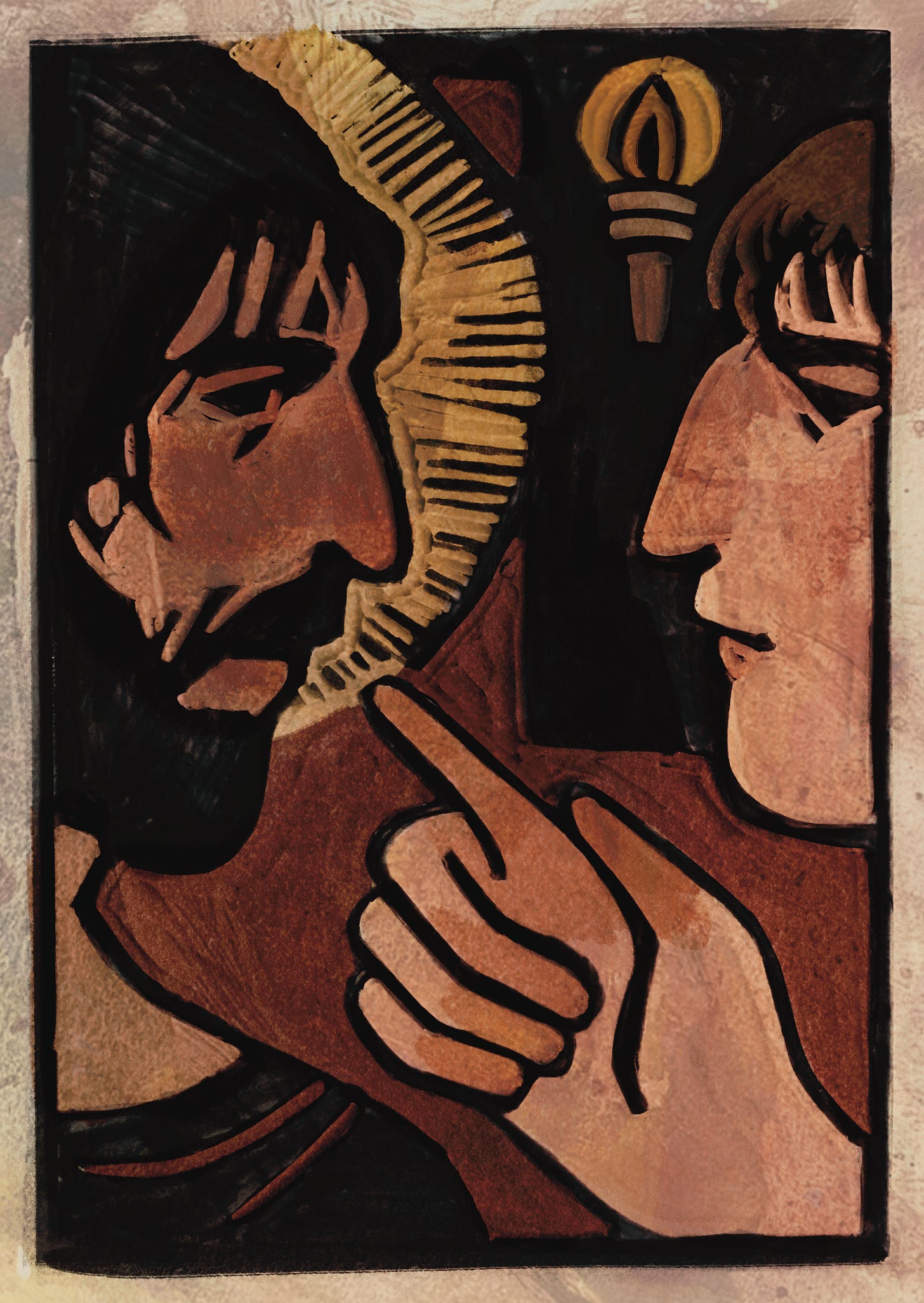

A torch shines clearly on Jesus, Peter, and James. The man holding the torch is Judas.

Judas hands his torch to one of the high priest’s servants and walks toward the tree. Then he kneels down next to Jesus. “Master,” he says, and he kisses him.

Jesus stares as Judas rises, and his voice sounds more tired than Peter can remember. “Did you have to do it with a kiss?” Jesus says.

*

After that, everything happens so quickly, it’s difficult later to recall. Two of the high priest’s servants come, grab Jesus roughly by the arms, and drag him up. James draws his sword and warns them to stop, but they don’t. He brings the sword down on one of them with a rough hacking motion. The sword misses the servant’s head, but takes off a chunk of his ear. The servant screams, and men from all over the garden come running. James curses his clumsy fisherman’s arms and raises the sword to strike again.

“Put that away!” says Jesus. “Whoever lives by the sword will die by it.” Then he places his hand on the side of the servant’s head and the bleeding stops.

The servant touches his ear and stares at Jesus. Two of the Temple guards take Jesus’ hands and tie them behind his back. James slips back into the shadows and hides.

“I came back to the Temple when you asked me to,” says Jesus. “You could have taken me then.”

The guards start to drag Jesus forward, and a soldier joins them.

“Have we found any of his fighters yet?” the soldier asks.

“I don’t need fighters,” Jesus says wearily. The guards laugh: if anyone could use some fighters, it’s this prisoner. They’re about to tell him so, but he speaks again first. “Don’t you know I could call down twelve legions of angels now if I needed them?” Jesus says, looking up into the hollow darkness of the night sky.

And for a moment the guards don’t dare turn around, don’t dare look up—their prisoner’s eyes seem so calm and certain, they’re afraid of what they’ll see if they do.

A Roman soldier stares at them and at this strange Jew, then shakes his head. He calls in the men who are still searching the garden, and the whole party heads back toward Jerusalem.

In the dark space between two trees, James shudders as he watches their torches grow distant and cold. He doesn’t know what to do—or what he’s done.

*

Peter follows from a distance, knowing but only half-caring that he might also be caught and arrested. He doesn’t want to lose sight of Jesus.

Jesus looks defeated. Though he’s walked through the night many times before, he can’t seem to keep pace now with the guards beside him. They drag him and push him: Peter hasn’t seen them beat or cut Jesus yet, but there are already bloodstains all over Jesus’ clothes.

The guards pass by the fortress and head into the upper city. They walk down streets where Peter helped a stranger carry water and pass the house whose owner saved a room for his master, the house where Jesus’ mother and the other Mary are asleep. Peter wonders if he should stop and wake them, if he should warn them the world seems to be falling out from under his feet, that everything feels wrong. But he doesn’t want to lose sight of Jesus, so he passes the house and follows the guards and soldiers a few more blocks until they walk into the courtyard of the villa that belongs to the high priest.

Peter stands on the street a few houses down. His legs feel empty and his throat is drier than the crisp Passover bread. But he pulls his shawl up around his face, walks into the courtyard, and hopes everyone will assume he’s another of the high priest’s servants.

*

It’s the middle of the night, but the witnesses have already been gathered. A man from Jericho testifies that a hundred or more fighters from his city followed Jesus to Jerusalem and that when the beggars called Jesus the Son of David, Jesus blessed them for it. He says he heard Jesus saying something about secrets on the road up from Jericho and suspects he was making plans for a revolt.

The high priest seems convinced by this evidence, but the attending jurists disqualify the testimony on the grounds that too much of it is indirect, or else relies on unsubstantiated assumptions.

Peter recognizes the next speaker and pulls back further into a shadow. This witness is from Galilee. He used to follow Jesus. He testifies about having heard with his own ears how Jesus offered a man forgiveness of sins, and relates having sat outside a tax collector’s home where Jesus was staying one evening while several prostitutes went in. Peter knows he has to hide, but he wants to shout. Any other night he’d be willing to go to prison for the truth, but tonight he knows he can only help Jesus by staying free.

The jurists disqualify the second accusation after learning the man couldn’t see into the house to know with certainty what happened there, and the first accusation when they learn that although many have heard from different sources of Jesus’ claim to forgive sins, no second direct witness is present to substantiate the claim as required.

Next, the jurists themselves testify they heard Jesus speak against the law in the Temple. But though both are sure this event took place, each of them remembers Jesus’ words slightly differently, so they inform the high priest that their testimonies, also, should be considered invalid.

The high priest begins to grow frustrated. “Tell us yourself,” he says to Jesus, “did you bring men with you to Jerusalem for a revolt? Do you claim the power to forgive any sins they commit in the process?”

The jurists start to explain that under the most expert interpretations of Jewish law, a confession is not admissible as evidence, but the high priest isn’t interested. “Can you explain away the things they’re saying? Don’t you want to defend yourself?”

But Jesus doesn’t say anything. Even if he wanted to defend himself, thinks Peter, he looks too exhausted to speak.

“Who are you?” asks the high priest. “Are you a fraud or a prophet? Are you a lawbreaker or a saint?”

But Jesus doesn’t even meet the high priest’s gaze.

“Are you the promised one?” the high priest asks.

Jesus looks up, then, and answers—not in everyday Aramaic, but in sacred Hebrew. “Ehyeh,” he says, which can mean either “I will be” or “I am.”

“Ehyeh asher ehyeh,” says Jesus. I will be whatever I want to be, or I am who I am.

Peter hangs his head, but he can still hear the high priest rip his own robe as a sign of shame. It’s all over now, thinks Peter. All over.

“You all heard exactly what words he said,” says the high priest. “We’re all direct witnesses now of his blasphemy.”

The jurists nod solemnly. There’s no need to disqualify this evidence.

*

Some of the guards spit in Jesus’ face. Others hit him.

When Peter looks away, a young servant meets his eyes. She looks at him closely. “Weren’t you with him in the street yesterday?” she says. “Are you one of his disciples?”

Peter wants to get out of this place. He wants to get out and go tell the others what happened, so he can’t afford to be caught.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Peter says.

Across the courtyard, the guards are blindfolding Jesus. They take turns hitting him and shouting “Prophesy who did it!” as they laugh. While the young woman watches, Peter slips away to the porch.

He hasn’t been there long when he hears another woman whispering: “Isn’t he one of them? I’d swear I saw him in the Temple,” she says to the servants near her.

“One of who?” says Peter loudly. If he leaves while they still suspect him, they’ll tell someone he’s running off.

The woman blushes. “I was just saying you look like someone I saw in the Temple a few days ago,” she says.

“I haven’t even been to the Temple this week,” says Peter, and then realizes how odd that must sound at Passover. “It’s just always so crowded this month,” he adds. “Are you from here, then?” says one of the women.

Peter hesitates. Will they believe him if he lies?

“You must be one of them,” she says, “I can tell by your accent.”

“So everyone with a Galilean mother is a criminal?” says Peter. “I don’t know him!” he says, and he swears for emphasis, hoping that will end the conversation.

On the far end of the courtyard, the guards take the blindfold off Jesus. Jesus looks out onto the porch, right at Peter.

A rooster crows.

Peter runs out into the street, and he doesn’t stop crying until he gets back to the house with the upper room where the women are sleeping.

*

Morning comes to Jerusalem: the sun’s first rays waking the dormant vibrancy of the Temple’s white and gold, the dewdrops savoring the twinkling moments in the light before they dwindle and disappear, the birds’ songs replacing memory’s echo of the Passover psalms.

Morning comes to Jerusalem, but for the scattered apostles, it’s as frightening as the previous night.

Simon and Matthew make their way toward Bethany in the darkness and hide on the hillside above the village, waiting for the others. When the light comes, they notice Philip and Thomas are hiding nearby, but wait to make sure they’re not being watched before they call to them.

Andrew, Nathanael, the big Judas and the little James hide outside the gates of Jerusalem, waiting for pilgrims to enter the city so they can slip into the crowd to look for their Master.

James and John head to Bethphage, where the men from Jericho are staying. They know fifty men don’t mean anything against the powers of the city, but they need to feel like they’re doing something to rescue their Master, so God can make up for the rest.

In the house in the upper city, Peter tells the women what happened. Salome tears her robe in shame and anger when she hears how the guards abused God’s chosen one; Mary from Magdala studies Peter’s face as she struggles to accept the impossible words coming from his mouth; Jesus’ mother gathers her things and asks where her son might be now.

And outside the sheep gate of the Temple Judas sits, alone: looking tranquilly over at the Roman fortress where Jesus is being kept, waiting for the legions of angels to come.

*

The governor has a problem. Sometimes he feels he’s had nothing but problems since he was sent here to the rough edge of the Empire, this edge that always seems on the verge of tearing itself apart. It’s a terrible place to have to rule: the Samaritans in the province hate the Jews, and the Jews are prone to riot over any under-punished Samaritan provocation.

And Jerusalem is a disaster. The lower city people hate the upper city people just like anywhere else, but here they think they hate the Romans instead. The upper city people are terrified of the impoverished lower city people—but instead of finding comfort in the Empire’s might, their fear keeps them focused on the order of their old priestly traditions. And because of their shared, strange religion, both kinds of people would rather die than accept something as simple as army banners with standard insignia being brought inside the city walls.

The governor’s hope has been to make it through this day without trouble. He’s having several petty criminals crucified, but he also has to execute a man who started a short-lived revolt. For that execution, he has the support of the upper city people, but he’s been nervous about the lower city people, who take every common robber for a hero sent from their god. So he’s been patient. He’s waited for a holiday, when attention is focused elsewhere and when an influx of wealthy overseas Jews could add stability.

But the high priest has complicated the governor’s day. He’s brought in a popular preacher the upper city people also want executed. And when the governor said: I’m busy today, the high priest said: this man is telling people he’s the king of the Jews.

The governor wants to be very clear on this recurring point. His firm position is this: Jerusalem is no longer a city for kings. Judea has a governor, and that’s all it needs. There’s no such thing anymore as a king of all the Jews.

But he hadn’t planned on making that point today. And he doubts he can quietly crucify two popular figures, each with his own supporters and sympathizers, in the same afternoon.

The governor walks out to his balcony, yawns and stretches under the warmth of the morning sun. It’s going to be a long day.

*

“Wait here,” says Jesus’ mother to Peter. “Unless you don’t think you can trust the owner of this house—we can help you get out of Jerusalem to find a safe place to hide.”

Peter remembers his first meeting with the rich man, how it seemed as if he’d been waiting for word of a visiting teacher, saving the room for the Master that would come. “I trust Joseph completely,” says Peter. “But where are you going and why should I wait?”

“I want to be close to my son,” says Mary. “But you said they recognized you last night, so it’s not safe for you to come with us.”

“You were there in the Temple with him too,” says Peter. “Are you sure it’s safe for you to go?”

“Don’t worry,” says Mary, and gives Peter a strange half-smile. “We’re women: no one pays attention to us.”

*

James and John keep interrupting each other as they tell the story to the men from Jericho.

“Do you know who took him?” the men ask.

James nods. “It was mostly Temple guards,” he says, “but there were some Roman soldiers with them.”

One of John’s old disciples sighs. “Temple guards would be good news,” he says. “The religious courts here aren’t allowed to kill anyone.” He tugs at his beard. “If the Roman soldiers take precedence, though, your Master is in serious danger. This governor isn’t ashamed to kill decent men by the dozens.”

“What do you think we should do?” asks James.

“I say go straight to the fortress,” says the man. “And if Jesus is there, we petition the governor to pardon him.”

“Will he listen to us?” asks John.

“He’s listened to a peaceful protest before,” says the man. “Though he did threaten us all with death first. But if he didn’t kill us then, he probably won’t now.”

The other men nod their assent, but the man asks John and James each one more question before they go.

“You’re certain they didn’t get a good look at you?” he asks John.

“It was late, and I’d fallen, so my face was covered in dirt,” John says.

“Then come with us,” says the man, “you may be useful.” He turns to James next: “You said you tried to cut off someone’s ear?” he says.

“I was trying to split open his head,” James says. “Cutting his ear was an accident.”

“Stay here and don’t let anyone see you,” the man says.

*

Once they’re inside the city, Andrew sends the big Judas and the little James back to the house in the upper city to make sure the women are safe. Then Andrew and Nathanael start their search for Jesus.

They start by asking people if they’ve heard anything about a teacher from Galilee who was taken prisoner in the night. They’re surprised at how many people immediately ask if they mean Jesus. No one knows what happened to him, but many seem to care deeply. Andrew and Nathanael don’t get any news, but find themselves sharing what little they know again and again, until their own accounts start circulating back to them as rumors. Soon everyone they talk to says Jesus was taken prisoner in a garden outside the city. Each has a different way of explaining what happened in the night, but none of the stories tell where Jesus is now.

*

“Do you think your old friends would fight for him now if we asked them?” Matthew says to Simon.

“No,” says Simon. “But if the high priest has him killed secretly and thrown in a ravine, they may know where we can recover the body. And if he is still alive, there’s a good chance one of them will know where he is.”

“He’s still alive,” says Thomas. “He has to be. Didn’t he tell us not to be afraid of the high priest?”

“Yes, but if Simon’s friends are likely to know something, we should go to them,” says Matthew.

Simon hesitates. “On the last trip south,” he says, “before I knew you as well . . .”

Matthew nods.

“What happened?” asks Philip.

“I told them about the work Matthew used to do,” says Simon.

“I’ll stay here and make arrangements for us to get somewhere safe if you can find a way to come back with him,” says Matthew. “You three go.”

“He never sent us anywhere alone,” says Simon. “Thomas should go with you: he knows how to find a safe place. It will be enough if Philip comes with me.”

“We’ll find a place,” says Thomas. “And when you find Jesus, be careful who you trust. Whoever told the high priest’s men about the garden probably told them about the house in Bethany, so we wait for each other at the hiding place near the crossroads.”

*

The high priest’s men tell the governor about Jesus’ crimes. He has blasphemed, he’s slandered their law, he’s claimed divine powers, he’s led the faithful astray. Clearly, they’re jealous of him. These religious Jews are always jealous of each other’s influence: it’s like an endless fight between harried priests and sages for control of the whole worthless, downtrodden pack. Following the politics between the various sects and personalities is as exhausting as it is tedious—the last governor tried and rotated through five high priests in ten years. This governor has no desire to create the same instability as his predecessor and does his best to remain aloof from such conflicts. He suspects it will be best to leave this prisoner in the high priest’s hands.

“When he says he’s king of the Jews, does he mean it as a political claim—or a religious one?” the governor asks. “He’s told tax collectors to leave their work and follow him,” says the high priest.

“Flog him,” the governor says to his soldiers.

*

The women are gone well before the big Judas and the little James find the right house in the upper city again. But the owner of the house wants to know what’s happening.

They decide to tell him everything. He gets very quiet as he listens.

“I’m an influential man,” he says after thinking for a moment. “Do you think there’s anything I can do?”

“Do you know the high priest?” asks the little James.

“There were soldiers there, so he might also be with the governor,” says the big Judas.

“I’ve talked with both of them before,” says the owner, and he sighs. “Wait upstairs with Peter for now,” he tells them. “Tell the servants I said to feed you well if I’m not back by tonight.”

*

“The high priest didn’t hesitate to give him to the Romans,” says one of Simon’s old friends before Simon can even greet him. “Now can you see why it’s so important to fight?”

“Is he all right?” asks Simon.

“The high priest doesn’t need to hand men over unless he’s looking for a death sentence,” says Simon’s old friend. “But as far as I’ve heard, the governor’s only had him whipped so far. Our man could hear the screams from outside the fort, so your Master must still have been alive.”

Philip feels sick. He has to lean against the wall to keep his balance.

“Can you help us?” asks Simon.

“Do you regret how he treated us the other night?” says his old friend.

Simon clenches his jaw so hard his teeth hurt. “I’m sorry I came to you today,” he says, and he walks away, back toward the fortress, even after his old friend shouts after him to forget about helping Jesus and watch out for himself instead.

*

John and the men from Jericho gather outside the fortress.

“Are you ready to die for your Master?” one of them asks John.

“Yes,” John says.

“Are you afraid of death?” asks another.

“No,” says John. “I just don’t want to leave him again.”

“Good,” says the first. “The governor’s power comes from our fear. So if his soldiers draw their weapons and we face them calmly, he’ll hesitate. Because he can feel he has no power over us.”

*

On his way up from the lower city, one of Simon’s old friends sees Andrew. “Your Master is being held in the fortress at the north end of the Temple,” he says. “Come with me. I’ll get you two weapons you can hide under your clothes, and I’ll take you there.”

*

The governor sees Jesus’ back first, glances at the deep stripes of cuts shaped like letters from an old Persian inscription as he passes. He turns around to face his new prisoner and motions to a soldier to lift Jesus’ bent head.

“Are you the King of the Jews?” the governor asks, speaking slowly and clearly in his best Aramaic. As he waits for an answer, he watches closely for signs of character, for anything that might indicate how much of a threat this man is.

He doesn’t see any fire in Jesus’ eyes, only resignation. He barely notices when Jesus speaks.

“You said it,” Jesus says, and the soldier lets go of his chin.

The governor looks at the prisoner’s bowed head and the bits of dried blood scattered over the front of his body. “I don’t see anything wrong with this man,” he says to the high priest.

*

John and the men from Jericho pray to God for protection before they start to sing from a psalm:

God won’t sustain a throne of injustice—but they make persecution the law! They gather against the souls of the righteous, and condemn innocent blood.

They sing those two lines again and again until others fill the square and join them. They keep singing when soldiers come out of the fortress and line themselves up along its walls in formation, and they keep singing when the soldiers draw their swords.

*

When he hears the noise in the courtyard, the governor remembers how much he hates Jewish songs. Songs that praise their god and deny all others, that forecast blessings for the Jewish faithful and curses for the rest of the world. Songs that promise divine deliverance or else glorify martyrdom.

The governor is tempted to have his soldiers charge the crowd before it grows any more, but since there could easily be wealthy citizens of other provinces in the square this time of year, he lets the song go on.

Then the governor gets an idea. He steps out onto the balcony, and motions to the crowd for quiet.

“I want to wish you well on your holiday,” he says. “And to commemorate it, I’m going to start a new tradition.” He waits a moment while confused whispers pass through the crowd, then goes on. “Every year at this feast-time, I’m going to offer a gift to you people. I know that some of you are upset that Barabbas will be executed today,” he says, and watches the square closely. A few people seem surprised, but not many. He’s fairly sure no one knew he’d planned on having Barabbas killed today, so he assumes the quiet means most of the people here don’t care. “Others are upset about a new prisoner named Jesus, who says he’s your king.” He watches the square closely again. More people seem to react to this one—good.

“I’ve decided to let one of them go,” says the governor. He waits for a cheer, but it doesn’t come. Maybe he needs to give the announcement some time to sink in. “Tell everyone in the city about the choice of pardon,” he says. “I’ll come back in an hour and ask who you want.”

The governor walks back into the fortress and lets out a great sigh. It’s too late to execute anyone quietly, but now he’ll be able to execute one of his controversial prisoners with full public support. He’d prefer to be done with the robber from the desert. But if he can’t have that, there will be some comfort in seeing the hope-crazy Jews choose to execute a would-be Jewish king.

Maybe he’ll be able to salvage this day after all.

*

The crowd in the square starts to break up as soon as the governor steps back inside. Simon’s old friends run to spread word to all their kinsmen and supporters about the coming choice. The men from Jericho tear their robes in mourning at the prospect of having to play a part in condemning a man to death, but hold their ground toward the front of the crowd, so the governor will be able to hear them well when they call out for Jesus.

The Galilean pilgrims in the square have heard of Jesus, but want to know who Barabbas is. Most of the Jerusalem natives know about Barabbas, but many have to ask about Jesus. Few of the pilgrims from abroad have a clear idea who either person is and try to find out enough to know who to call for.

As they move through the square, Andrew and Nathanael find Simon and Philip, then are found by John, the two mothers, and Mary from Magdala.

“What do we do now?” asks the young Mary.

“We stay here so the governor can hear us well from the fortress,” says Nathanael.

“We should talk to people in the crowd. They need to know why to ask the governor to let Jesus go,” says Andrew. “I’m a fast runner,” says Simon. “I can probably reach Bethany and return with a group of the villagers and our people from Galilee. That will be worth more than trying to persuade people we don’t know in such a short time.”

“I’ll go with you,” says Philip. “I may fall behind on the run, but I can help spread the word once we’re there.”

“Go quickly,” says John. “Andrew and Nathanael can talk with the men in the crowd; Mary and my mother can talk with the women.” He looks at Jesus’ mother. “I’ll stay here with you,” he says. “We don’t want you to get lost in the crowd. You should be the first to greet him when he’s freed.”

*

Simon and Philip aren’t even out of the city when old friends of Simon grab them.

“Where are you going?” one asks.

“That’s not your concern,” says Simon.

“Our concern is to make sure it’s Barabbas who gets released today,” another says, and Simon feels something blunt hit him on the back of the head. He stumbles forward and is shoved to the ground. Someone kicks him in the ribs, a stick slams down on his back, and someone else kicks him in the face so hard he loses consciousness.

*

Peter can’t have been waiting in the upper room of Joseph’s house for more than a few hours, but he still feels trapped and anxious by the time Joseph returns and comes up the stairs, dressed in his finest robes.

“Did you see the high priest?” Peter asks.

“No,” says Joseph. “His servants received me graciously, but he’d already gone to the governor.”

Peter doesn’t know what to say. He feels weighed down by his worries, as if his soul is made of stone.

Joseph is looking at him intently. “Your Master,” he says. “Is his heart as honest as his face?”

Peter meets the merchant’s gaze. “No one is purer,” he says.

“There’s very little purity in our governor’s heart,” says Joseph. “So I’m hoping he’ll let your Master go if I offer him a bribe. My servants are gathering the gold I have here to begin with, but we can promise more if he demands it.”

“Thank you,” says Peter. “We are in your debt.”

“There’s no need for thanks,” says Joseph. “And no debt to be paid. I’ve traded enough to know what’s worth any price.”

“Peace be on you and your household,” Peter says.

“For that blessing,” says Joseph. “I owe you thanks.” He smiles at Peter and he goes back down the stairs. It’s not long before Peter can hear him and his servants leave the house.

That’s when the weight of Peter’s anxiety returns.

“We should go,” Peter says to the other two apostles. “There must be something we can do to help him.”

“It won’t help anything if you get caught,” the big Judas says. “Though it might make things worse.”

“Tell me what I can do then,” says Peter. “Tell me anything.”

“Try to get some sleep,” says the little James.

*

The governor comes out onto the balcony at the end of the hour. The square must be twice as full as before.

“Who do you want me to pardon?” he asks. “Jesus!” shouts half the crowd.

“Barabbas!” shouts the other half.

“Who?” says the governor.

“Jesus!” yells half the crowd.

“Barabbas!” screams the other half.

The two factions start to push and shove each other. The governor starts to worry his plan to avoid a riot might end up causing one.

“Since you can’t decide, we’ll cast lots,” he says. “Unless you’d prefer I crucify both?”

The people in the square stop pushing and fall silent. “Very well,” says the governor. “One of them will be spared.” He motions to a servant, who brings him a vessel of water. “You are my witnesses that we left it to the gods to decide their fate. My hands are clean of the crimes of these men and of the verdicts that fall on them.”

As the governor washes his hands, his soldiers drag the two prisoners out in front of the fortress. Their hands are tied behind their backs. So that everyone can tell which prisoner is Jesus and which is Barabbas, the soldiers have given Jesus a crown of thorns.

The high priest comes out next with two small stones: one smooth and the other rough. A line of condemned criminals follows to serve as witnesses of what the lots decide.

The soldiers move Jesus to the right and Barabbas to the left.

The high priest throws down the tiny stones.

One of the condemned men takes a close look at them. “The rough stone fell to the right,” he calls out. “The king of the Jews will be crucified.”

The soldiers cut Barabbas loose, and push him forward into the crowd. Simon’s old friends and their people cheer. The high priest’s supporters nod in grim satisfaction.

Jesus’ mother clings tightly to John’s arm.

*

Though Jesus seems barely able to carry his own weight, the soldiers put the beam of the cross on his back. He cries out in pain when the heavy wood falls across his fresh wounds, but he manages to stagger forward, half-dragging the cross beam behind him, through the narrow streets of the north end of Jerusalem.

Some soldiers are standing guard at the city’s north gate. They seem to be searching the crowd for something: they keep stopping men, questioning them, then turning back some and searching others—the ones with northern accents.

Andrew grabs Nathanael and pulls him down between two fish stands in the marketplace near the gate. “They must be looking for us,” he whispers. Then he gets a still tighter feeling in his chest: “And we’re carrying weapons.”

They don’t want to leave Jesus. But they’d rather leave now on their own than be caught on the way out of the city and have Jesus see them get arrested.

The guards are so busy with the men, though, they hardly look at the women. They pay so little attention to them that they don’t seem to notice an older woman is leaning for support on the arm of a young Galilean man.

*

When Jesus collapses and can’t seem to lift the beam of the cross again, the soldiers make a bystander carry it. He’s a merchant, one of the Jews who’s been successful enough abroad to make the journey to Jerusalem each year for Passover.

He will never forget this day. He will tell his sons about it and they will never be able to forget the story either.

*

John and the women don’t dare come too close to the hill where the soldiers finally lay down the cross. It’s an ugly, lonely, barren hill: short, half-dead grasses cling stubbornly to a thin layer of dried-out dirt over a skeletal outcropping of rock.

They nail his hands and feet to the wood. Neither Mary can stand to watch, but they won’t leave him.

The soldiers set up crosses all over the hill. So many men suffer on so many crosses.

Jesus cries out again in pain.

My God, my God, why have You forsaken me? Why are You so far from helping me, and from the words of my roaring?

The sky begins to darken. A cold wind blows and the older Mary tenses, then weeps. Her son is dying: why is she worrying about the cold on his bare skin?

Oh my God, I cry in the day time, but You don’t hear me. I cry through the night and never fall silent.

The soldiers are talking and laughing. How can they ignore all the agony around them?

But You are holy, and Yours are the praises of all Israel. Our fathers trusted You: they trusted, and you delivered them.

One of the high priest’s jurists is arguing with a soldier about the sign above Jesus’ cross. “Why did you write ‘King of the Jews’?” he says.

But surely I am a worm and no man: reproached by men, and despised by the people. Whoever sees me laughs in scorn; they throw open their mouths, they shake their heads and say: “He trusted the Lord to deliver him! If the Lord loves him, why doesn’t He deliver him?”

One of the high priest’s servants lifts up a cup of wine. “Almighty king!” he shouts. “If you’re thirsty, come down from the cross and take a drink of this.”

Mary holds on to John’s arm as tightly as she can. Someone told her once a sword would pierce her heart, and she can feel it there now, running straight though her chest.

But You’re the one who took me out of the womb: You made me hope when I was on my mother’s breasts. I was cast on You from the womb: You’re my God since before I left my mother’s belly.

They lift the wine cup up to him on a stick, but he won’t take any.

Be close to me! because trouble is near, and there’s no one to help. Bulls have surrounded me, the strong bulls of Bashan. They gape at me with wide mouths, like ravening, roaring lions.

He’s been up there for hours.

I am poured out like water. All my bones are stretched thin. My heart is like wax that has melted down into my bowels.

It gets darker and darker, though it’s the middle of the day.

I can count all my bones: they look and stare up at me. My heart is like wax that has melted down.

The soldiers get bored and gamble for his clothes.

My heart is like wax that has melted.

After six hours on the cross, Jesus cries out:

“My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?”

Everyone stares. It’s the first time Jesus has spoken. “He’s calling for Elijah!” says Judas, and he pushes his way past the high priest’s servants to fill a sponge with vinegar. He puts it on a long reed and gives Jesus a drink. One of the high priest’s men tries to pull him away, but Judas elbows him hard in the ribs. “Leave me alone!” he shouts. “Elijah is coming for him!”

But Elijah doesn’t come. Jesus cries out again, loudly. And he dies.

Judas looks up at him.

Judas needs to scream, but the scream won’t come out.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Original artwork by Sarah Hawkes.

To receive each new chapter of The Five Books of Jesus by email, first make sure to subscribe, then click here and select "The Five Books of Jesus."