The Deeper Sorrow

Reflections on What Ails Us, One Week After the Death of Charlie Kirk

In the days since the assassination of Charlie Kirk, we have been left to grapple as a nation with both the meaning and the causes of his death. Indeed, in the 48 hours after the killing, The New York Times summed up the state of the nation by publishing an article entitled: “After Charlie Kirk's Death, Voters Agree Something is Wrong in the US.” But the rub, of course, comes in identifying just exactly what that is. As a doctor, I believe diagnosis is the single most important part of any treatment—if we mislabel an infection as an autoimmune disease we won’t just be unhelpful, we will actually make things worse. And so, this essay is my attempt at running a deep diagnostic on our body politic to probe the underlying illness that plagues us in hopes that we can then move toward healing. In sequence, I will make four overlapping arguments:

Partisan rhetoric obscures more than it reveals. Familiar talking points from either side of the aisle will do little to help us.

The infrastructure of the current interaction of the internet—wherein humans are divvied up and exploited, often by appealing to our basest instincts, all so that a select few can profit handsomely—constitutes a major portion of the problem but is still a symptom.

What most deeply ails us is that we have attempted to render ourselves boundless and placeless—but are finding that neither is possible and that the attempt leaves us hollow, atomized, adrift, and alone.

The only ultimate remedy is to embody a deeper boundedness, to cultivate an authentic sense of place, and to foster affection toward place, the Earth, and each other.

With all of this, we may not arrive at the precise or definitive answer—the causes are myriad, complex, and interwoven—but my hope, nonetheless, is that the exploration will help to heal what ails us.

I

Public political responses to Charlie Kirk’s killing have unsurprisingly varied with the political affiliation of the person responding. In some corners of the Internet, we have seen responses that focus on the danger of young men who live their lives heavily online (the shooter seems to have been intensely involved in violent video games). Likewise, some have focused on America's ongoing problem with gun violence and the easy availability of such a deadly weapon. In other left-leaning corners of the web, some have suggested that Mr. Kirk helped to fan the flames of the fire that eventually engulfed him because of his sustained intemperate rhetoric over many years.

On the other side of the spectrum, however, those on the right have largely condemned the killing as an example of hateful leftist rhetoric made real. According to many right-leaning politicos, the killing of Mr. Kirk should hardly be surprising because, in their minds, the political left hates America, everything it stands for, and those who choose to speak out in defense of patriotism and a “traditional” way of life. In this telling, the killing is little more than the reductio ad absurdum of what all left-leaning folks would really like, anyway—which is that people like Mr. Kirk would just sit down, shut up, or, even better, entirely disappear. The problem is not with access to guns, or online video games, or the incautious rhetoric of someone like Mr. Kirk; no, from this perspective, the difficulty is that those on the left denounce Donald Trump and all who support him as authoritarians, bigots, and thugs. Many on the right argue that it is hardly surprising that a disturbed young man might decide to take into his own violent hands the fight against those who are labeled ascendant fascists.

Clearly, some of the arguments above have merit; partisan political points can sometimes be helpful in thinking about what is happening to us. However, there are three problems with the above analysis. The first is that partisan rhetoric and vitriolic reactions are so well-worn and ingrained that it will be virtually impossible to make any headway in these discussions if we fall back to our practiced partisan positions. The second is that partisan rhetoric about such deep and thorough problems can distract us from more thorough exploration. And the third is that, paradoxically, participation in the cycle of partisan accusation and counter-accusation can inadvertently perpetuate the pathologies at the root of the illness we are trying to cure. The ideas articulated in the preceding paragraphs may not be the root of the problem but they are certainly a symptom of it—and continuing to propagate them not only keeps us from addressing the deeper issues but may make the illness worse in the process.

II

To better understand the root of society's ailment, let’s consider that the structure of the Internet has come to comprise our public square. Writing in The Atlantic in the aftermath of the shooting, Charlie Warzel, an astute observer of the interactions between technology and society, reflected on how the current infrastructure of the Internet contributes in often invisible ways to the problems we are trying to solve. I recommend the essay in its entirety. I was especially struck by this observation:

But it is hard not to notice that, in the aggregate, something poisonous is in the architecture of the internet's platforms and the way that our technologies demand not just our attention, but our most heightened emotions. This is not an environment for good faith politics. These platforms are governed by algorithms that tend to prioritize engagement above all else, amplifying the loudest, most shameless users because their voices will draw in other voices. This attention is worth good money, both to posters who can harness it, as well as the tech companies.

I think Warzel is moving us much closer to the root of the problem with this analysis that the problem is not with one set of political ideas, but, rather, with the way that we now engage in politics, period. In an age when “watching the news” has become an anachronism, and where most information about the world is gleaned through social media feeds, we need to scrutinize how the presentation of that information shapes how we understand the world.

Author, thinker, and psychiatrist Anna Lembke, who works and writes from her post at Stanford University, has observed over the past few years that we live in an age of addiction—we are all effectively addicted to everything. Her argument is that the human brain is designed to scavenge hits of dopamine, a chemical that is secreted when we experience pleasure or strong emotion. The rapid changes of a digitalized world in the twenty-first century, however, have greatly outpaced our evolutionary biology. After all, there was a time when pleasure was offered to most humans as a rare treat. Now, however, we have easy access to pleasure-bringing stimulants that are almost literally ubiquitous: calorie dense snack food, pornography, social media likes, the triumphalist self-righteousness of holding forth on any social media platform.

But in all this, the innovation that is perhaps most ominous is the near omnipotence of the invisible algorithm. The companies that control social media platforms, after all, do not have any great or noble motive. Whatever they may say about wanting to help their users, and though they may make passing gestures toward altruism, they prioritize profit above everything else. This has always been true in capitalist economies, of course, but now, for the first time in history, the commodity that is most commonly exploited is not just natural resources but also the very people who think they are getting online products for free.

Algorithms play a unique role in the delivery of information to human brains. In previous eras, the information delivered to most of us depended on imperfect but devoted gatekeepers, people like news anchors Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow. Their success depended not on the size of their audience, but on the trust they established. These and other gatekeepers surely fell victim to their own biases, blind-spots, and prejudices—but to some significant degree, they tried. And that trying—striving for objectivity in the presentation of “the news” without fear or favor—mattered.

The current situation is very different both because of the intimate and ceaseless access that information streams have to our hearts and brains and because of the motivations central to the way those information streams are managed. For example, in the history of humanity there has never been something like a smartphone. A smartphone may not be literally and physically sewn into the human organism, but, in many ways, it might as well be. Many adults and teens in Western countries never go anywhere without their smartphone, checking the devices endlessly every day. The old New Yorker cartoon showing a couple sitting together in bed, scantily clad, looks like it would be a prelude to something more passionate—instead of warming to each other, the couple is staring at the dull light of their respective phones, each ensconced in an individual online universe, physically close but worlds apart mentally, emotionally, and sexually.

We scarcely realize and yet incessantly experience that the content that comes to us through our smartphones, and especially through social media platforms, is increasingly dictated by algorithms whose exact mechanism remains almost entirely opaque but whose sole function is increasing profit for those who run them. Most of us carry around the vague idea that engaging with a social media platform is a way of being in community with those we know. But increasing research shows that most of our time on social media algorithms is not dedicated to content that comes from people we are “friends” with, but rather to content that is meant either to keep us on the site longer or to monetize our attention on behalf of those who want to sell us things. Thus, with a precision and subtlety that increases by the day, we are faced with a bait and switch: we believe we log on to engage with some form of community, but instead find that we are increasingly subject to the whims and profit motives of those who would turn us into an infinitely exploitable commodity. We live in a moment that author Nicholas Triolo describes in an article in Orion magazine:

The pervasive want, the hoarding, the gobble gobble that has pummeled you from all angles for as long as you've known will be difficult to relinquish. The empire needs you to think and live and want along straight lines. You've been conditioned to walk the line, summit the mountain, follow the path of prescribed progress until you're too exhausted and too baffled to ever consider thinking we're living in a different shape.

What is most striking about this “gobble gobble” is the degree to which content dictated by algorithms is able to shape the contours of reality. Because so many of us now rely on online platforms for the “news” that tells us what is happening in the world, the power of algorithms has effectively riven the world not just in two, but into increasingly divergent alternate realities where we inhabit different informational worlds.

These algorithms alarm me. Those who design, launch, and control them may claim or even believe they have altruistic motives, but abundant evidence suggests that, when push comes to shove, corporate motives—especially maximizing profit—take priority at the expense of seeking the common good. The point here is not that their motives are malicious—obviously, I cannot see into their heart. Rather, the issue is that the companies they have created have grown so powerful that even if their motives are good, the unintended and too often ignored consequences of their actions can wreak havoc on our civic discourse and the health of the republic.

Writing soon after the shooting of Charlie Kirk, essayist, observer, and New York Times columnist Zeynep Tufekci describes the ways in which depictions of killings are themselves commoditized by the machine of social media, becoming a form of chillingly voyeuristic content that we bandy about online as if it were fodder for our water cooler chats.

At the end of her trenchant essay, she writes,

Meanwhile millions, perhaps billions of people have watched and rewatched Kirk’s and Zarutska’s last moments as if they were video game clips or movie scenes instead of the dying moments of a man leaving behind young children or a young woman slain in the prime of her life. Virality achieved, but humanity—theirs and ours—lost.

In this way, internet culture has transformed the flesh, bone, blood and reality of a living, breathing, soul-filled person into so many pixels, normalized to spread hate and anger, monetized to stoke rage and win more dollars. The internet has become a battlefield that robs us of what makes us human.

III

For all of this, however, the infrastructure of the internet remains a symptom—not the primary illness. As much as that totalizing architecture matters, and for all the control it exerts over so much of our lives, an even deeper rot nonetheless festers even deeper down.

In my view, two of America’s most important twentieth-century writers are Wallace Stegner, a professor at Stanford University, and Wendell Berry, a farmer in Kentucky and a prominent social and cultural critic. They come closest to helping me understand the true difficulty that underlies so much of modern culture and discourse.

In his essay entitled “The Sense of Place,” Stegner examines the peculiar American obsession with what is often thought of as “forward progress.” Referencing ideas like manifest destiny—the conception that European colonizers were meant to move West and occupy the entirety of the American continent—Stegner observes that people in the western part of the United States, especially, seemed possessed of an inextinguishable desire to be always on the move.

He refers to westerners as often being driven by a “hasty, shallow, and restless” disposition, and that citizens of the United States are often “acquainted with many places, but rooted in none.” Further, he says that we often seem to “value [our] rootlessness, though to the placed person [we] show the symptoms of nutritional deficiency, as if [we] suffered from some obscure scurvy or pellagra of the soul.” Stegner seems to be gesturing towards a basic wanderlust in our collective disposition that was best characterized one hundred years before him in Tocqueville's Democracy in America. There, Tocqueville wrote of our peculiar tendency to remain forever uprooted. He said:

Fortune awaits them everywhere, but not happiness. The desire of prosperity has become an ardent and restless passion in their minds, which grows by what it feeds on. They early broke the ties that bound them to their Natal earth, and they have contracted no fresh ones on their way. Emigration was at first necessary to them; And it soon becomes a sort of game of chance, which they pursue for the emotions it excites as much as for the gain it procures.

What is striking about the Tocqueville quote, especially, is this: many US citizens would read the quote and understand it as a compliment. What, after all, is more American than drive and ambition? In many corners, we imbue Westerns with romantic allure. We still think of “progress” and “expansion” as unalloyed goods. We still look to the far reaches of our vision and believe that is where happiness awaits us. But in all of this, we seem unaware that such restlessness can harm us—such ambition can become our undoing. We seem to be a people who are drawn forever toward the distant horizon and the temptations that it portends, not recognizing that in questing toward that forever receding destiny, we become blind to the beauty and deaf to the music already around us.

Stegner and Berry offer a different, more productive, and truer way. In the same essay cited above, Stegner writes

So I must believe that, at least to human perception, a place is not a place until people have been born in it, have grown up in it, lived in it, known it, died in it—have both experienced and shaped it, as individuals, families, neighborhoods, and communities, over more than one generation. Some are born in their place, some find it, some realize after long searching that the place they left is the one they have been searching for. But whatever their relation to it, it is made a place only by slow accrual, like a coral reef.

Stegner reminds us that the western rush toward the new, the consumerist assurance that more is always better, and the unending quest to enrich ourselves and to hoard for ourselves all that we can—these tendencies come with a steep but too often unrecognized price. In all our Tocquevillian rushing toward the distant horizon, we have forgotten how to dwell in a place. We have forgotten that the only way to exist in a form that is meaningful and succoring, nourishing and nurturing, beautiful and meaningful, is to allow ourselves to be bound in place and time. We have become convinced by modern society and by the evolution of digital technology, especially, to believe that our rootlessness has no cost—to think that we can sever all meaningful local ties and somehow recreate them in the ether of the Internet. But eons of collective wisdom suggest that this is a mirage and that our society is spooning sand into our mouths hoping forever that it will somehow slake our thirst.

To really understand the extent of this problem, we turn now to the writing of Stegner’s student, Wendell Berry. His writing helps us perceive how, in and because of our boundless ambition, we have collectively lost the ability to cultivate community—and then he helps us think about the consequences of losing it. In a 1992 essay entitled “Sex, Economy, Freedom, and Community,” Berry writes

A community identifies itself by an understood mutuality of interests. But it lives and acts by the common virtues of trust, goodwill, forbearance, self restraint, compassion, and forgiveness. If it hopes to continue long as a community, it will wish to—and have to—encourage respect for all its members, human and natural. It will encourage respect for all stations and occupations. Such a community has the power—not invariably but as a rule—to enforce decency without litigation. It has the power, that is, to influence behavior. And it exercises this power not by coercion or violence but by teaching the young and by preserving stories and songs that tell (among other things) what works and what does not work in a given place.

This passage describes the root of the problem provoking this essay. Yes, it may be true that guns are too easily available, and, yes, it may be true that the left talks too broadly about rising authoritarianism or fascism. Yes, it is undoubtedly true that the architecture of online communities plays an even deeper role in fostering the kind of collective civic rhetorical warfare that has delivered us to our current fraught moment.

But even that recognition is too shallow.

Berry, in this passage, brings us much closer to the root. In that very last line, Berry hearkens back to the importance of an idea that both he and Stegner emphasize: the centrality of place to our conception of what it means to be human. In effect, what both authors are arguing is that humans are bounded creatures. We are only capable of knowing—really knowing—a limited number of people. We are only capable of pausing in a given number of places. We are only capable of existing in relationship to a particular place and time.

The central animating forces behind American expansionism generally, and the driving motive of capitalism more generally suggest to us—though we may not recognize the suggestion—that we are meant to be boundless beings. That we will be happier and thrive more fully if we expand forever the circle of our friends, the expanse of our wealth, and the things that belong to us. These all suggest, in fact, that the point of life is not to establish ties to anyone or anything but simply to have more “ties” to everywhere and everything. Indeed, this would seem to be the sine qua non of the Internet: the allure and the suggestion to be everywhere all at once, to relate to everyone all the time, and to know everything that is going on with everybody—endlessly.

Berry’s and Stegner’s writings matter precisely because they remind us eloquently and emphatically that endless boundlessness cannot be. Because we are bounded beings, boundlessness will forever elude us. What the digital world offers, of course, is not true boundlessness, but the appearance of it. It cannot grant us community, so it instead offers us ephemera masquerading as ties that bind. It cannot offer real belonging—actual acquaintance with other enfleshed beings— so it gives us instead an endless stream of likes and applause emojis, or, in darker times, a similarly false sense of disapproval or even disavowal. It cannot offer genuine transcendence and so it offers us, instead, pictures of increasingly impressive resolution, as if they could somehow compensate for the lack of the real thing.

This is the cultural and political economy birthed at the intersection of capitalism, technological advances, rapaciousness, simulated boundlessness, and the American desire to be forever expanding. It is the topography upon which we are attempting to grapple with problems whose depth and scope we most often do not understand just as a fish does not know what it means to be in water. These are the forces against which we must wrestle. This is the world we have created and that we must now seek to unmake.

IV

Toward the end of the classic children's book, The Little Prince, the titular character has a conversation with a nameless fox, in which the fox asks the prince to “tame” him. The prince clearly does not understand what the fox has in mind and so he asks the fox repeatedly to explain what it means to be “tamed.” Finally, the fox explains:

If you tame me, it will be as if the sun came to shine on my life. I shall know the sound of a step that will be different from all the others. Other steps send me hurrying back underneath the ground. Yours will call me, like music, out of my Burrow. And then look: you see the grain fields down Yonder? I do not eat bread. Wheat is of no use to me. The wheat fields have nothing to say to me. And that is sad. But you have hair that is the colour of gold. Think how wonderful that will be when you have tamed me! The grain, which is also golden, will bring me back the thought of you. And I shall love to listen to the wind in the wheat.

This passage vividly depicts what our current culture lacks, and just what we must regain. In all our desire to expand the scope of our acquaintances, our money, our influence, our pleasure, and everything else—in the ephemeral and reflexive world we have built for ourselves online, we are losing the ability to establish between ourselves the kind of ties that the fox is suggesting. “Tame” may not be the right word here, being fraught with associations and phrases like “taming the wilderness.” What I believe the fox is really suggesting is that the key to life is the cultivation of affection. And that such cultivation can only really happen within the bounds of physical space and time—with the geography we can actually touch and the people who actually surround us. Affection, by its very definition, is a bounded virtue.

Ultimately, the most corrosive rot we detect at the foundation of the society we are building together is the disappearance of affection from so much of public life. A lack of affection most comprehensively characterizes the prelude to, the act of, and the aftermath from the shooting of Charlie Kirk. Obviously, one human publicly killing another in cold blood in broad daylight would seem to be the reductio ad absurdum of a lack of affection. But affection was also too often absent from the welter that ensued online after Mr. Kirk died. We are called to witness and to note with mourning how easily we now turn toward each other with hatred and, even worse, contempt. We need to see how entirely we have come to view other people as fodder for hatred and caricature rather than as beings fully invested with divine nature. We are so quick to dehumanize, to flatten and to demonize, so hasty to disallow others the grace and complexity of being fully human.

And it is also in this context that we come to a final irony—a punctuating tragedy—of life in the age of the algorithm. Over the last few months, stories have proliferated of those who become deeply enmeshed in the online algorithmic world and who try to establish a relationship with an algorithm. We hear talk of a man who was convinced by an algorithm that he had discovered a novel and world-changing mathematical theorem. Of the New York Times reporter who had a chatbot attempt to convince him to abscond with it on Valentine’s Day. And we hear at every turn of companions that will offer “friends,” “therapists,” and even “romance” in the form of digital companions. All of this tells us something simultaneously reassuring and unsettling: the need for affection and connection will not die. When we try to smother it beneath mountains of bits and bytes—it will refuse to die. Too often, however, in response, instead of turning to the actual humans who can offer us friendship, companionship, affection, and love, we beat back again and again against the digital tide, hoping against hope that somehow chatGPT or an AI girl- or boyfriend can bring us the caring we so desperately need. We are, as Sherry Turkle wrote, “alone, together.”

In this brave new world, we are so avidly and desperately searching for Aldous Huxley's “soma” that we have forgotten how to cultivate the affection that defines the relationships that constitute the heart of every meaningful life: relationships to the place in which we dwell, relationships with the other creatures and the landscape that surround us, and relationships with the people who make us most fully human. This loss of affection exists in a complicated downward cycle of mutual destruction with the political, technological, and capitalistic economy that we have brought into being. The great underlying problem of the profit-driven, capitalistic, algorithm-determined social media feeds we so often inhabit is precisely that they treat people and their attention as a commodity to be exploited rather than as fully human beings meant to exist in relationship with each other, relationships that must be defined by affection.

All of this brings me to the words of CS Lewis. In his book The Weight of Glory, he writes:

The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbor’s glory should be laid on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. It is a serious thing to live in a Society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.

Recognizing the divine in the humans around is the undergirding Christian principle that demands that we recognize the full extent of the problems corroding and corrupting our culture.

Strangely, the reaction to this knowledge will often not look like something we do so much as something we abstain from doing. While our ailing collective body politic yearns desperately for the life-giving blood of affection, that blood cannot come rushing into the heart until what is already in the heart is emptied out. Our collective reflex might be to rush into what cardiologists call “systole” (the motion of the heart pumping blood out to the body), but that “systole” must first be preceded by a great collective “diastole” (the part of the cardiac cycle when the heart chamber, already empty, expands to make room for the next milliliters of blood to rush in).

As we think about the tragedy that has unfolded over the last few days, and as we ponder how to respond, it may be that the greatest wisdom lies not in what we can rush to do, but in how we can begin to let go. That may look like the path of wu wei: finding the ways in which I can be still and let that stillness be part of the solution. Are there quick and reflexive words I can leave unsaid? Are there social media feeds from which I can unsubscribe? Are there ways of being frenetic and everywhere at once in which I can choose not to indulge? In other words, it may be that in order to withdraw from the frantic, totalizing, devouring tumult, we will need to begin by recognizing that we cannot be everywhere all at once, and that, in fact, to try to be everywhere is to effectively be nowhere. To try to “friend” or “follow” everyone is to be meaningfully tied to no one. And to imagine we no longer need to be bound by place is to give up the ties that would bind us to where we are.

As I dwell in this stillness, as I learn to let go, to stop listening, to unsubscribe, to step back, to quiet myself and my surroundings, I may face an encounter with what Anna Lembke called “the great quiet.” In that space, I discover uncomfortable recognitions about myself and the ways in which I have allowed my personhood and my attention to be divided, exploited, and commoditized. Once I have come to this recognition, I can turn my attention to the question that can ignite a cultural revolution and an individual transformation: How can I begin—right here, right now—to reestablish the ties that will bind me to the places and people that matter most? In what meaningful ways can I spend the rest of my life cultivating affection with the place where I live, the world that is around me, and the people who constitute the beating heart of what it means, for me, to be human?

Tyler Johnson is a medical oncologist and associate editor at Wayfare. To receive each new Tyler Johnson column by email, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for On the Road to Jericho.

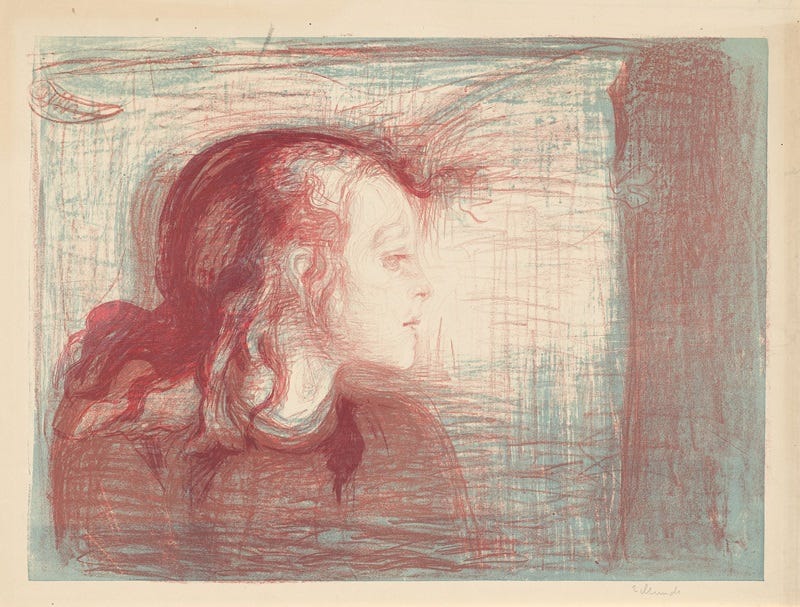

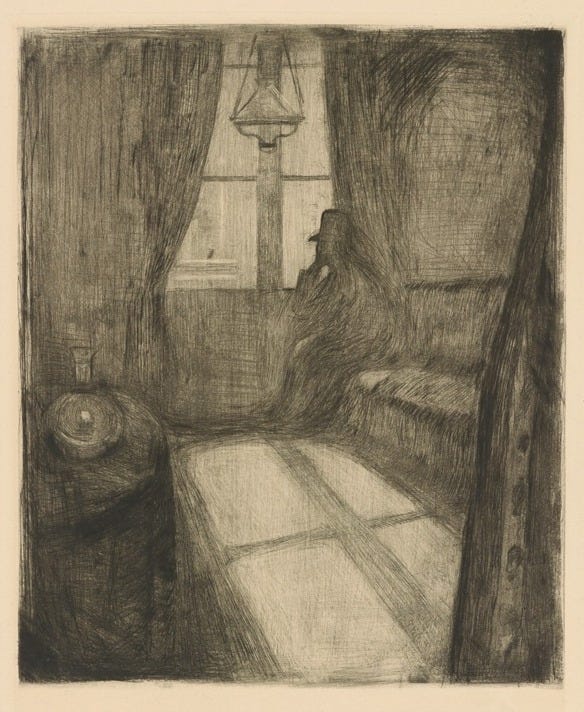

Art by Edvard Munch.

👏🏻❤️