Origen was the principal Christian proponent of the spirit’s premortality. His views did not comport entirely with Restoration beliefs—he believed we transitioned to mortality to improve upon the conduct in our previous state of existence. Our life on earth is a moral hospital as much as it is a school for souls. (Given the woundedness of our condition—both metaphors seem entirely apt!). One of the loveliest aspects of his conception was his belief that some spirits did not enter mortality in order to improve their standing with God or to repent and reform; they had achieved a condition of holiness, but wanted to accompany the rest of us here in order to uplift, comfort, and assist. Dwelling like starfish in the tidepools, these beings do not appear miraculously as beings of light when called upon, but reside among us as fellow laborers in the ebb and flow of life’s constant struggles. These men and women “are ordained to suffer with others” for fitting out the state of the world and to offer service to those below them. They were “brought down from the higher and invisible conditions to these lower and visible ones” to “serve the whole world.”

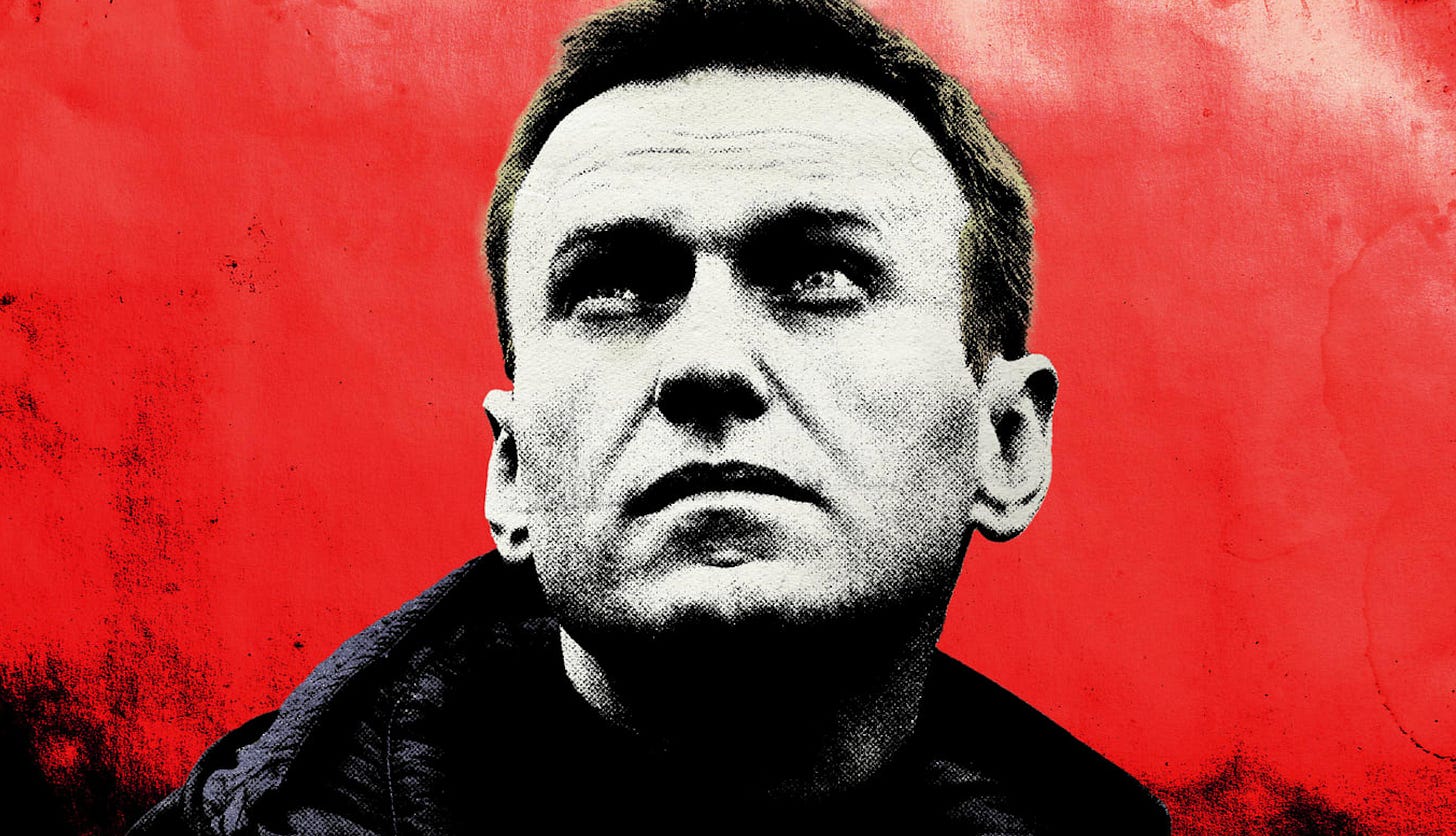

On 20 August 2020, Alexei Navalny was poisoned with the Novichok nerve agent, following his tireless unmasking of Kremlin corruption. For years he mobilized tens of thousands to stand against the most brutal and horrific forms of human evil, including armed domestic repression and the invasion of Ukraine. In 2014, refusing to flee Russia, he said “If I want people to trust me then I have to share the risks with them.” In 2021, he miraculously recovered from the Novichok poisoning in Berlin, and insisted on returning to his homeland. He knew he was flying home to certain imprisonment and likely death. “I don’t want to give up either my country or my beliefs,” he said explaining his decision, so unfathomable to others. Imprisoned above the arctic circle, he died in February 2024, just over three years later, aged 47.

Courage seems a weak word for the nobility of character evident in the actions of individuals like Navalny (and thousands who have been roused to costly sacrifices by his example). And I would not resist an interpretation that sees in such heroic martyrs an example of just what Origen speculated: a soul of a different order than I am, ordained “to suffer with others,” “brought down” from above to serve us lesser humans.

To admire the noble and deplore the vile is itself a witness that the source of the Good exists and is revealing itself to our inferior though kindred selves. After all, as more than one theologian has pointed out, (Alvin Plantinga for one), to ask indignantly how evil can exist in a universe God created is already to admit that some true standard of the Good does exist independently of human constructs. If only good and bad things existed, we would not need a word like “evil” to differentiate ethnic cleansing from Bubonic plague.

No mystery lies behind the power of transcendent deeds in the face of human evil to inspire me. But they always carry a trace of the unsettling as well. Perhaps it is because no moral labor is required to love the Good when it blazes forth so conspicuously. It is commendable but also easy to affirm such evident moral beauty.

At all times, but especially in a time of national divisiveness such as our own, we are called to a more daunting challenge. Politics gives us all spiritual cataracts; we strain to glimpse the good that is obscured by our own—and others’—fervor. Some theologians virtually gave up the task. “If we would hold the true course in love,” preached one in the seventeenth century, “our first step must be to turn our eyes not to man, the sight of whom might oftener produce hatred than love.” Turning away our eyes is hardly the path to acquiring empathy; it concedes defeat too easily, claiming a love only in the abstract. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story of a young man suddenly thunderstruck when he witnesses a “moment of tenderness . . . in one of the most abominable men”—and whose life is transformed by the glimpse. William Egginton writes that these intrusions of the Good into lives of mediocrity and even corruption led the philosopher Immanuel Kant to elaborate a whole theory of morality:

“We see evidence for the existence of this moral law everywhere, he said; in the least impressive of our fellows, in the most abominable of men, we can at times glimpse an act of righteousness, a spark of goodness. And when we do . . . we can feel our spirit bow down in respect.”

Dichotomous evaluation is easy—whether to venerate the admirable, or to dismiss all of human nature as depraved. Fathoming the complexity of human desires and motivations is harder work. Even the legacy of Navalny is a complicated one—as is the case with all lives, however crowned with heroic gestures they may be. At the present moment especially, it is tempting to hope for figures of transcendent stature to rescue us from the cynicism and suspicion we have allowed to overwhelm our national ethos. Our urgent need on the homefront is to find more nuance in caricatures of evil we have flung about promiscuously in public and private discourse. We are heirs of a theological tradition that gives us reason to see each other more charitably and generously and perceptively than we are at present doing. And science increasingly supports a more charitable and nuanced view than popular accounts of our neighbors would have us believe. The most widely reprinted article ever published in a scientific journal was Garrett Hardin’s six-page paper from 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Hardin’s thesis was that when cooperation for a public good competes with self-interest, self-interest will always triumph. “An appeal to independently acting consciences selects for the disappearance of all conscience in the long run.”

Doubtless the ease of cynicism, like the ease of admiring heroic gestures, makes a thesis like Hardin’s popular. Less widely known is the fact that a scholar named Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel Prize for her work that demolished Hardin’s despairing view. “The humans we study,” she said in her acceptance speech, “have complex motivational structures.” And we succeed in working together for the common good “far more frequently than expected.”

My own attempt to find glimpses of the goodness in those I cannot understand at present will be to try to model the father tenderly eulogized by Brian Doyle:

“The way he stared at your face as he spoke, with all his soul open and alert for your story, and how he would wait a few beats when you were done, in case there was a coda coming, and then he would lean back and consider what you had just said. . . . I want to celebrate his listening for it is now nearly gone from this world, and it was a rare and extraordinary and unforgettable thing.”

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."