The Beauty of Holiness

Sing, O daughter of Zion

When I was almost eight, earnestly trying to do what was expected of a soon-to-be-baptized member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I decided I needed to participate in the customary fast on the first Sunday of the month. Skipping breakfast before church was easy, but not eating lunch left me cranky by two or three in the afternoon. My long-suffering but exasperated mother responded to my whining by suggesting a few distracting activities, all of which I pronounced “dumb.” She finally said, not hopefully, “maybe you could read the scriptures. Maybe Psalms?” I liked the idea of Psalms—a beloved schoolteacher had given me a pocket-sized “Testament and Psalms,” which I kept in my box of treasures but hadn’t really read. I took it down to my favorite basement reading spot—a remnant of green carpet laid next to the woodstove, where the comforting warmth from the stove generally made up for the annoyance of the splinters of wood that worked their way into the carpet and thence occasionally into a reclining reader’s elbows.

I dutifully read for a while, interrupted occasionally by impressively loud stomach grumblings, and had almost given up when I got to Psalm 29 and was arrested by the phrase “worship him in the beauty of holiness.” I knew from Joseph Smith’s story that sometimes a scripture could leap from the page and change the world, and I recognized this as my own Epistle of James moment, which would cleave my life into before and after. (This sounds very dramatic. I was a dramatic child. But it is also the truest way I know to tell the story.) I did not cry, not then. But I did go and get my violin and start practicing the most beautiful thing I knew, and I worked myself into tears with the little sighing grace notes in the third measure of the Brahms Waltz in Suzuki Book 2.

It is a strangely precise memory, perhaps because the details laid out the only nearly infallible mechanism for accessing the transcendent that I have discovered in my life: the recognition—often faint—of an idea, a “stroke of thought” that evokes a kind of longing that is not assuaged, but heightened and intensified by trying to capture the feeling in words or music. I know the details, because I have lived them, with slight variations of the carpet color and the text and the music involved, hundreds of times.

Curiously, I experienced that moment not as a revelation about God, but as a moment of self-revelation. That is, I was aware more or less instantly that this would be both method and content of my testimony. What I know, and nearly all I have been given to know, is the aching, joyous longing for the beauty of holiness. I don’t really believe Keats’s famous couplet: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” There is plenty of truth in the world that is ugly, or harsh and bracing, and I have fallen for some beautiful lies. Nevertheless, the things I believe most deeply about God—the tiny list of things I am sure of—have come to me as traces of beauty tinged with a yearning something like homesickness. I am not convinced that beauty is always truth, but the entanglement of beauty and truth is, for me, a wellspring of joy.

The problem with this story is that it ought to be the backstory of a talented musician or composer or painter or sculptor, and I am none of those. I am a middling violinist with rusting skills and a solid utility alto. It is also not a particularly promising origin story for someone who is going to be spiritually nurtured in the workaday, low church traditions of Latter-day Saint worship. My peculiar mode of access to the spiritual realm, combined with a notable lack of any evident artistic gifts, and the coincidence of being born into a cheerfully practical religious tradition that does not generally invest overmuch in artistic excellence in worship, is a recipe for restless frustration. I am saved by moments of unexpected grace and what at least one exhausted Primary teacher called “sheer cussedness.”

I occasionally went back to the Psalms as I grew up, and I started to recognize the poetry in Isaiah and felt its tug. But there was easier poetry to be captivated by—Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poems for young people, then her sonnets; my mother’s beloved Emily Dickinson; George Herbert, whose “Easter Wings” inspired a few attempts at shape poems that even at fifteen I could see needed to be not merely discarded, but burned; Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Pied Beauty,” which was (in what I am happy to call a miracle) a handout on the Sunday I graduated from Primary into Young Women. My father warned me sternly, after yet another assignment as youth speaker which I fulfilled mostly by reading e.e. cummings over the pulpit, that I should not get all my theology from poetry, to which I responded that Isaiah seemed to have been Jesus’s major theological influence, so I didn’t see what the problem was. (A prime example of the aforementioned cussedness.)

I went away to college and had a freshman year straight out of a college brochure or an overwrought nineteenth-century novel about the delights of the mind. I took courses in politics and literature, German lyric poetry, philosophy, and music. I sang in a choir that went to New York to perform in Carnegie Hall on my eighteenth birthday. And I sang in the chapel choir, discovering the possibilities for creating beautiful, reverent worship services with professional organists and conductors and auditioned singers. On Sundays, I would spend the morning in the majestic chapel in the middle of campus, feeling my heart leap at the first chords of the Old Hundredth and the simple psalm paraphrase of William Kethe:

All people that on earth do dwell,

Sing to the Lord with cheerful voice!

Him serve with mirth, his praise forth tell;

Come ye before him and rejoice.

A service typically included three or four hymns, plus choral prelude and postludes, an anthem, and a choral benediction or amen, often some service music or a communion anthem. Always there were responsive readings of Psalms.

My senior year, a new conductor, freshly arrived from England, decided to teach us Anglican chant. It is hard to describe how I felt in that first rehearsal figuring out how to read the tune at the top of the page and make the words fit with a series of instructions provided by a few simple symbols, mostly |, *, ⋅, and an occasional —. The first attempts were awkward, but after a few minutes, I felt like I was speaking my native language for the first time. I didn’t have words for the sense of joyous homecoming. I had felt that way in a Latter-day Saint service only once, fleetingly, when I was very small, and a fine organist opened up all the very big stops for the pedal as we sang “Far, Far Away on Judea’s Plains.”

Maybe, I thought, that’s to be expected. After all, it’s hard to know what coming home feels like if you have never left. I tried not to notice that the way I felt singing Psalms in this ancient tradition seemed akin to what many people describe when they convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

It wasn’t that I didn’t have a testimony of my own church. I did. I had had a few powerful experiences I couldn’t explain away, and I wanted to be faithful to the truths I had received in Latter-day Saint contexts. But what to do with the sweetness of this recognition that felt like homecoming?

I would like to say that I have figured it out, or that my conviction of the truth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints overwhelms every uncertainty. But that isn’t true. I struggle to make sense of how like a fish out of water I feel at church sometimes, and I have to work hard to figure out how to contribute meaningfully in a church where so many people seem to connect to God in a different way than I do. Have I missed my calling because I stayed in my religious home? What does it mean that the gifts that seem most precious to me are seldom wanted where I have promised to offer everything?

I have no answers to these questions, or to the most painful question of all—why was I given the gift of loving music, and not the gift I have always wanted most—to be good at singing the praises I hear so clearly in my heart? The years seem only to bring more questions.

But some of the questions are gracious—big enough to stretch my understanding and make faith possible. One comes from a beloved Christmas carol, “In the Bleak Midwinter”: What can I give him?

My chronic grief about not being a great musician makes me wonder earnestly about the disconnect between what I think God would like and what I can actually give. It occurs to me sometimes that most of what we bring to the altar is not nearly as valuable as we suppose. The difficulty of figuring out what the Lord wants from us is illustrated in Genesis by Cain’s rejected sacrifice, articulated again in Samuel’s insistence that “to obey is better than sacrifice,” and the psalmist’s recognition that “thou desirest not sacrifice; else would I give it: thou delightest not in burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.” The Nephites are instructed that their “burnt offerings shall be done away, for I will accept none of your sacrifices and your burnt offerings.” And just before the Saints at Kirtland are asked to give a tithe of money to build the temple, a new kind of sacrifice, they’re reminded that “all among them who know their hearts are honest, and are broken, and their spirits contrite, and are willing to observe their covenants by sacrifice—yea, every sacrifice which I, the Lord, shall command—they are accepted of me.”

Perhaps we need to be told exactly what to sacrifice because we aren’t very good at recognizing what is valuable. Maybe Paul’s description of gifts within the body of Christ isn’t just about other people’s gifts that we wrongly think are less worthy than our own, but about our estimation of what it is we ourselves have to offer.

Nay, much more those members of the body, which seem to be more feeble, are necessary:

And those members of the body, which we think to be less honourable, upon these we bestow more abundant honour; and our uncomely parts have more abundant comeliness.

For our comely parts have no need: but God hath tempered the body together, having given more abundant honour to that part which lacked.

Maybe artistic gifts, like all the others, are useful for bringing us to the place where we can offer all that we really have to give—our brokenness, our need, our yearning to know and be known.

And this brings me to the biggest and most helpful question for me: What is beautiful? Or, in Gerard Manley Hopkins’s lovelier formulation, “To what serves mortal beauty?” and “What do then? How meet beauty?”

A lot of debates about Christian aesthetics worry through these questions, starting from the premise that the beautiful is costly, in money or time or unequally distributed talents, and that those resources ought to be used for more practical kinds of discipleship. Other askers of these questions are troubled by the possibility that art will draw attention to itself and away from God. Latter-day Saints seem to be nervous about the arts on both counts, in ways that are clear more from our practice than our doctrine: choir practice is never going to take precedence over ward council, and maintaining the floor of the basketball court is usually a higher priority than tuning the pianos. The art that is part of our worship is not chosen by artists or trained critics, but by men with ecclesiastical authority. Their appraisal of what kinds of art and music are suitable for Latter-day Saint worship carries more weight than the considered judgment of people who spend all their lives thinking about what is beautiful or true; we are, institutionally, wary of people who think that beauty could tell us something about God that authority cannot. I don’t know any artists or musicians in the Church who don’t chafe at these constraints.

And yet, on my more patient and charitable days, I am able at least to ask whether these constraints may tether us to what Hopkins calls “God’s better beauty, grace.” After all, the closest thing to an aesthetic theory for the Restoration presents itself in section 42 of the Doctrine and Covenants, in a passing reference to beautiful garments in Zion:

And again, thou shalt not be proud in thy heart; let all thy garments be plain, and their beauty the beauty of the work of thine own hands. . . .

Thou shalt not be idle; for he that is idle shall not eat the bread nor wear the garments of the laborer.

And whosoever among you are sick, and have not faith to be healed, but believe, shall be nourished with all tenderness, with herbs and mild food, and that not by the hand of an enemy. . . .

Thou shalt live together in love, insomuch that thou shalt weep for the loss of them that die.

This is beauty not as aesthetic, but as ethic, part of the consecration of all human striving within a community committed to a tender regard for every member and for the labor that sustains bodies and souls. And while it might be read to minimize the importance of beautiful things, and certainly is a warning against aesthetic snobbery, it also offers the possibility of sanctification for working to make things beautiful; it insists that skillful handwork can matter deeply in God’s economy of time and effort, which makes me hopeful about choir rehearsals in Zion.

It begins to answer the question “what is beauty” in a more expansive way than our usual post-Enlightenment, post-Romantic theorizing. It situates the beautiful in the life of a community, insists that it is not only a matter of self-expression. It recognizes, in a way that we sometimes fail to attend to in other contexts, that making things beautiful is WORK, not the magical efflorescence of “talent” or “passion” or any of the flimsier things we sometimes call “art.” And it allows for the possibility that the beautiful will exist right alongside the terrible—idleness and pride, illness and disease, even death. It is a human and earthbound beauty that God commends to us.

Here finally is the truth of it for me: God wants to tell us, all the time, that creation is good, that this world and all that is in it is beloved. The stirrings I felt as a child by the woodstove and with my squeaky little violin were real and true, but they were not meant to pull me towards transcendence so much as to push me towards love. Beauty is an index to the divine not because it lifts us out of the earth, but because it lets us see the ways we are part of it and lets us hear God whispering that “it is very good.” God’s love of the creation includes not only the rose, but the thorns and the dirt and the earthworms and even the aphids. What God calls beautiful is not only the expertly performed Bach prelude, but the toddler running to his nursery teacher with arms outstretched, a loaf of bread baked for the sacrament by one of the high priests, that one Sunbeam yelling every song in the Primary program, the surreptitious passing of tissues during testimony meeting, a stack of variously shaded and wrinkled hands laid together to give a blessing, the endless passing of signup sheets to help with moves, rides to Girls Camp, chapel cleaning, the sacrament of ham and potato casseroles after funerals. We build our part of Zion with wood and stone and mud, and then God promises to restore our wastelands and make our feeble gifts worthy of his habitation—he will, in Isaiah’s words, lay our stones with fair colours, and lay our foundations with sapphires, make our windows of agates, our gates Salvation and our walls Praise.

None of this makes me stop going to Evensong services and choir concerts and loving them. It doesn’t completely assuage the grief of not having enough time or talent to make the kind of music I long for. None of this is to say that I have become reconciled to bad music in our worship services, or that I don’t believe God wants us to work more diligently at creating beauty. It is only to say that I am, ever so belatedly, beginning to understand that worshiping God in the beauty of holiness is a different thing than worshiping beauty, and that holiness is beautiful in both the poetry of the Psalms and in the homely prose of a dutiful life. Indeed, I may say that I follow the admonition of Zephaniah:

Sing, O daughter of Zion; shout, O Israel; be glad and rejoice with all the heart, O daughter of Jerusalem.

The Lord hath taken away thy judgments, he hath cast out thine enemy: the king of Israel, even the Lord, is in the midst of thee: . . . Fear thou not. . . .

The Lord thy God in the midst of thee is mighty; he will save, he will rejoice over thee with joy; he will rest in his love, he will joy over thee with singing.

Kristine Haglund is a Wayfare Senior Editor, a past editor of Dialogue, and the author of Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal.

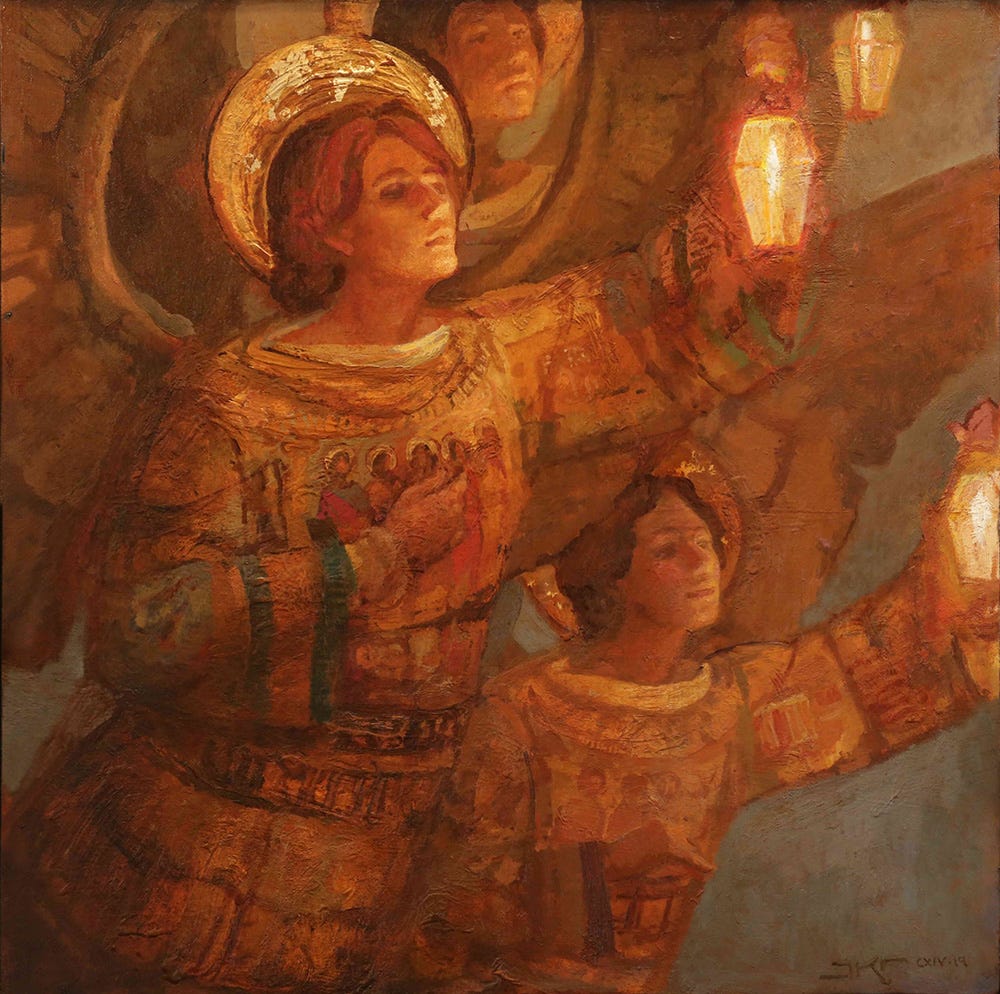

Art by J. Kirk Richards.

KEEP READING

NEWS

Latter-day Saint scholars Stephen Smoot and Brian Passantino will be speaking on their newly-edited volume, “Joseph Smith's Uncanonized Revelations” at Benchmark Books from 5:30-7:30 am on June 6th. While most of the texts featured in this volume are accessible in The Joseph Smith Papers, average readers will probably find it difficult to sift through all twenty-seven volumes of the papers to locate them. This book aims to remove that barrier to help facilitate access to these fascinating revelations and is available for purchase here.

The LDS Church crossed a major milestone in organizing Utah’s first Spanish-speaking stake, with intentions of adding more in the future. The newly formed stake is composed of ~1,600 church members from eight Spanish-speaking wards, reflecting the Church’s growing Hispanic and Latin American reach.

Journalist Sarah Jane Weaver has been named the new Editor of The Deseret News, notably being the first woman to hold the position since the paper’s founding in June 1850. She assumes the role after serving as the top editor of The Church News since 2017, during which time she expanded its reach more than tenfold among church membership. “I am honored to continue building on the strong foundation laid by many previous Deseret News editors and look forward to working with talented Deseret News writers, editors, photographers and designers to take the trusted voice of the Deseret News to a growing audience in Utah, the West and across the nation,” Weaver said.

May 15th marked the 195th anniversary of the Restoration of the Aaronic Priesthood. Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery were visited by John the Baptist on May 15th, 1829, who imparted the authority to perform baptisms, promising additional priesthood power to be imparted later. Speaking of the occasion to dedicate the renovated Aaronic Priesthood Restoration site in Susquehanna County in 2015, President Nelson recalled that “This was holy ground…The reason for such a profound feeling of reverence is clear. The restoration of the priesthood keys to the earth was crucial. Priesthood keys authorize men on earth to act and speak in the name of God.”

The completion of the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project 1988-2024 will be celebrated at the Gordon B. Hinckley Alumni Building at Brigham Young University on August 10th, 2024. Scholars Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack will each present on the scope, history, and major insights of the project and how they enrich our understanding of the Book of Mormon. An open house with the presenters, along with viewing displays, will take place from 12:00-1:00 PM, followed by the two presentations until 3:00 PM.

I love this so much. And I wish I could have known that teacher who gave out the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem to 12-year-olds.

I always love your wisdom and beauty in words. This essay is gorgeous, personal, and inspiring. I'm bookmarking it for frequent return. Thank you for sharing it!!