I have been arrested once in my life, for selling the wrong kind of art on the street. I had a date that night, and I was able to convince the precinct to let me go a little early so I could make it to dinner, but not before procuring my first (and hopefully last) splotchy-faced mug shot. Selling art on the street without a license is not illegal. However, the officer who arrested me determined that the particular art form I was selling (stained glass) was a craft, rather than art, and therefore was not protected under the first amendment.

What is craft, and how does it differ from art? This question, to me, strikes at the deeper issue of whose voice is deemed worthy of being heard, and I would define craft as art deemed “women’s work” that the consumer economy has chosen to devalue. In every society, women have gathered in groups to produce practical art forms in community. When I visited Samoa last winter, I learned about Tapa, a traditional form of ceremonial cloth stamped and painted by women to carry sacred meaning. Closer to home, my family for generations has gathered together at bridal and baby showers to tie quilts in community. We take turns leading “Sun Valley crafts” on family reunions, and gather for the highly anticipated annual “Christmas craftapalooza” and wreath making night. No holiday, and no family member over about two years old, is safe from crafting. Crafting is about creativity and beauty—in other words, art—but it is also fundamentally about community, relationship-building, and love. All of which makes it, to me, profoundly feminist.

Last week, the New York Times published a podcast discussion initially titled “Did Women Ruin the Workplace?” later rebranded “Did Liberal Feminism Ruin the Workplace?” The original title made for some fun memes, and drove some of my friends to cancel their subscriptions to the Times. In it, columnist Ross Douthat interviews socially conservative thinkers Helen Andrews and Leah Libresco Sargent on their critiques of liberal feminism as relates to how the workplace functions in the U.S. Libresco Sargent argues that the modern workplace has failed women by looking down on dependence in a species that is fundamentally interdependent, particularly during phases of women’s lives such as pregnancy and child rearing. In other words, the workplace has not risen to meet the inherent biological needs of women.

Andrews, meanwhile, argues that women are incapable of meeting the inherent needs of the workplace, at least when they form a relative majority in a given group. Per Andrews’s “great feminization hypothesis,” as outlined in her essay The Great Feminization, too many women have entered various traditionally masculine professions due to affirmative action and anti-discrimination efforts. As a result, they have weakened the workforce, infusing it with “wokeness,” and replacing meritocracy, hearty debate, and rule of law with emotionality, passive aggressiveness, and cancel culture. Per Andrews, “everything you think of as ‘wokeness’ is simply an epiphenomenon of demographic feminization.” Cancel culture (a term Andrews seems to use interchangeably with “wokeness”) is “simply what women do whenever there are enough of them in a given organization or field.”

I was unfamiliar with the great feminization hypothesis prior to reading the NY Times piece, but I have since spent time with Andrews’s essay, and I think it deserves a place in the discussion about gender in 2025. As a physician who works in the fairly female-dominated field of pediatrics, I agree that there are typical changes that occur in group dynamics when groups are primarily female or male. I also agree with Andrews that the goal of feminism should not be to achieve numerical equality in every profession.

But I disagree with her on two main levels. First, rather than undermining institutions, I believe that the presence of at least a meaningful minority of women tends to enrich and strengthen the functioning of most groups. Second, my reason for believing we should not force numerical equality in every profession is not because women present an existential threat to the functioning of these professions, but rather because I am primarily concerned with wanting humans to live rich and meaningful lives, and I am not convinced that income generation is a good metric for this goal.

I am sure that there are some women who’ve chosen not to pursue certain careers because they felt pressured to stay home and raise kids, but I think there are far more women today who deprioritize careers relative to other aspects of life from a position of empowerment. I respect these women as fellow feminists (wanting to live a meaningful life is why I chose my career too!); and if anything, I think our society could benefit from more emphasis on non-income-generating care and community building for both men and women, rather than less. I’m convinced women belong in any workplace they feel drawn to; but I also want to live in a society that values work for the worth that it adds to the world, regardless of income.

Regarding Andrews’s thesis, while there is far more variation within genders than between them, statistical differences do exist between men and women, many of which relate to group dynamics. In the medical field, for instance, female providers on average tend to downplay their own status, ask more questions relating to social and emotional factors, and explicitly validate patients’ experiences. One study examining female vs male physicians’ patterns of communications sums this up as “a patient-centered communication style that inspires patient reciprocation and is likely to reflect a more intimate therapeutic milieu of heightened engagement, comfort, and partnership.” Other studies have supported Andrews’s argument that men are statistically more risk-taking and focused on competition over collaboration.

Whether these differences are learned or biological may not matter as much as recognizing that when leveraged wisely, both “masculine” and “feminine” patterns of behavior are beneficial to society as a whole. An extreme in any trait without the moderating effect of other traits tends to be suboptimal for a workplace or other group, and my preference is for groups that benefit from some of the competitiveness, risk-taking, focus on profits, and over-confidence of the average man, as well as the caring, creativity, collaboration, caution, and idealism of the average woman. But what do the data say regarding Andrews’s more ominous assertions? Does an influx of women in a given field lead to more emotional decision making, poorer outcomes, or less dedication to truth seeking and rule of law? Are “female modes of interaction . . . not well suited to accomplishing the goals of many major institutions”?

This argument does not appear to play out in my own profession. Men and women score equally on objective measures of affective variation (aka emotionality), and women are not statistically more likely to act based on emotion rather than rationality at work. Female physicians, for instance, are more likely than male physicians to follow evidence-based practice and clinical consensus guidelines in patient care, medicine’s form of “rule of law.” Female surgeons have fewer complications, possibly relating to their more methodical/slower operating times on average. Female clinicians spend more time with patients, are more likely to involve family members and patients in clinical decision making, which could be seen as more emotion-driven, but they also achieve lower mortality rates and readmission rates than male physicians in settings where patients are randomized to physicians based on call schedules. The data in my field of practice are clear: Women have not ruined the practice of medicine, they have improved it.

This is not to say that medicine would benefit from an all-female workforce. Men bring strengths to group dynamics as well; a collaborative approach is helpful, but more direct or assertive styles of communication, as are typically seen in all-male groups, provide balance, too. And I am not arguing that only men are to blame for any bad outcomes in medicine. To do so would be to fall prey to an upside-down version of a common error, which is to fault women when things go wrong.

Take “cancel culture,” which Andrews sees as a consequence of women’s biological drive to care more about empathy and group cohesion than reason. I agree with Andrews that cancel culture poses a danger to society, but I disagree that it is the fault of one gender or political leaning, and I disagree that it has anything to do with empathy or “wokeness.” One can certainly engage in cancel culture in feminine ways. But history abounds with more masculine examples of cancelation, from the Salem witch trials to McCarthyism, to Mao’s cultural revolution, and to the tone of our current political environment in which collaboration with one’s political opponents is far too seldom seen as a strength. Cancel culture is fundamentally about silencing and invalidating anyone with a perspective different from our own, and in that sense, it is a manifestation of contempt rather than empathy. It can be seen in arresting someone for selling the wrong kind of art, in the literal cancellations of newspaper subscriptions for publishing the wrong opinion article, and in the assertion that conservative feminism doesn’t exist in retorts to the NY Times piece published by Glamour and Ms Magazine. The knee-jerk reaction to the article itself proves one of the article’s central points, namely that feminism, narrowly defined, is being used by some as an ideological justification for shutting down debate by dismissing anyone with an opposing view. Not only are self-identified conservative feminists wrong . . . they don’t even exist!

But conservative feminists do exist, along with many other types of feminists, all of whom add to the rich tapestry of conversation about what it means to be a woman, to value women, and to respect them. First-wave feminists fought for my right to vote and to own property. Second-wave feminists argued for economic and professional equality, the leveling of gendered hierarchy. Of course these feminists are correct that women are equally capable of excelling in traditionally male-dominated fields, with minor partial exceptions relating primarily to differences in physical size, speed, and strength in athletics. At the same time, I agree with others that given some potential inherent differences on average between men and women, these differences should be celebrated, rather than diminished. Where one iteration of feminism argues that masculinity as expressed via patriarchy is harmful to women and should be dismantled entirely, another perspective labeled, perhaps, conservative or cultural feminism contends that typically gendered activities focused on home, parenting, and other non-income-generating pursuits should be equally respected as options women can choose not because they are oppressed, but because those forms of work are inherently meaningful. The New York Times discussion of Helen Andrews’s article uses the broad terms liberal and conservative to categorize different forms of feminism, but we could also draw distinctions between individualistic feminism vs collectivist feminism, ecofeminism, intersectional feminism, data feminism and more. Regardless of the inherent limitations of any terms we may use, the more perspectives we are able to hear and learn from, the better.

As a pediatrician, I am tremendously grateful to first- and second-wave feminists for making my own career path possible. At the same time, I appreciate that not all feminisms focus on individual career or economic advancement, instead centering family, relationships, strong communities, social welfare, or other goals as paramount. To me these approaches are complementary, a recognition that as humans we have both material and spiritual needs. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is inescapably patriarchal and hierarchical in ways that can be difficult to grapple with for many women (myself included). But it is also a church that places families at the center of the gospel. None of the hierarchies of church leadership endure after death in LDS theology, but families do, or at least can. In that sense, the trappings of ecclesiastical hierarchy—prophets, apostles, stake presidents, bishops, Relief Society presidents and the like—are temporary scaffolds present primarily to support the building of the foundational, enduring structure of family relationships. And who is primarily seen as responsible for building families in the church? Women.

Professionally as well, my ability to meet objective health metrics for patients is entirely dependent on non-income-generating work done by families and to a large degree by women. I examine kids in the office and have brief conversations going over history, diagnosis and plan, but the parent is the one who truly provides the actual preventive and medical care the vast majority of the time. In this sense, medicine is yet another scaffold that exists primarily to support the central structure of families. This pattern is common to many professions; humans do not thrive in isolation, and we owe our success as a society not only to economic structures, innovation, worker productivity and rule of law, but also to largely unrecognized and underappreciated forms of profoundly meaningful relational work done primarily by women. I am paid for the work I do professionally but not for my efforts as a mother, sibling, friend, partner, neighbor, etc. But is financial reward the best measure of worth?

In his book The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, Don Thompson explores the question of how contemporary art is defined and valued, with particular attention to a rotting preserved shark that was sold for $12 million as The Physical Impossibility of Death In The Mind of Someone Living. Thompson argues that prices in the world of contemporary fine art are shaped by the desire of the ultra-rich to flaunt their wealth by owning something everyone knows is exorbitantly expensive. “Works of art, which represent the highest level of spiritual production, will find favor in the eyes of the bourgeois only if they are presented as being liable to directly generate material wealth,” he states. In our overly consumerist society, this generation of wealth is achieved not solely through artistic talent (the top echelons of popular artists such as Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons don’t actually create much of the art they sell; they “conceptualize it,” and pay others to produce it) but through marketing, branding, and hype. “You are nobody in contemporary art until you have been branded,” Thompson explains.

Applying one narrow view of liberal feminism to contemporary art, the goal of women’s empowerment might be to have more female “top contemporary artists” who are selling works of arguable absurdity for millions of dollars. Certainly, economic measures like equal opportunity for financial advancement and equal pay for equal work are important, and my purpose here is not to argue against those aims, but rather in favor of expansive conversations about feminism that include other perspectives. After all, few would argue that a shark in formaldehyde marketed by a trendy brand of artist actually adds more insight or value to the world than a quilt made by an Amish community, or a piece of textile art inspired by traditional weaving. In light of that, should we be satisfied with the goal of solely having an equal number of women earning equal money in our current hyper-capitalist society? Or should we also seek to recognize the value and spirituality of more communal and traditionally “feminine” forms of art and work, as well as more “feminine” ways of engaging in professional spaces, and to elevate their role in our society, regardless of who chooses to engage in them? Is fine art, in other words, actually more valuable than craft? Or do we only view it as such because we aren’t very good feminists?

To be a feminist is to acknowledge, learn from, and celebrate the inherent worth and equality of women alongside men. That can mean clearing out misconceptions about where women do belong (everywhere) and don’t belong (nowhere), and what forms of work women can feel called to (all of them). It can also mean calling into question a solitary view of human relations that focuses only on “masculine” measures of success, such as individual achievement and competition, broadening those metrics by adding to them the value of interdependence and community. It can mean supporting women who choose to work in traditionally male-dominated fields, but it should also mean supporting women—and men—who choose to focus their efforts in traditionally female forms of work. A capitalist view of the world may value things based solely on their economic worth. But a spiritual worldview, and a feminist worldview that embraces all iterations of female empowerment, ask more from us.

Annie Edwards lives in Bountiful, Utah with her four kids and two dogs. She enjoys music, running, hiking, skiing, reading, working as a pediatrician, and crafting.

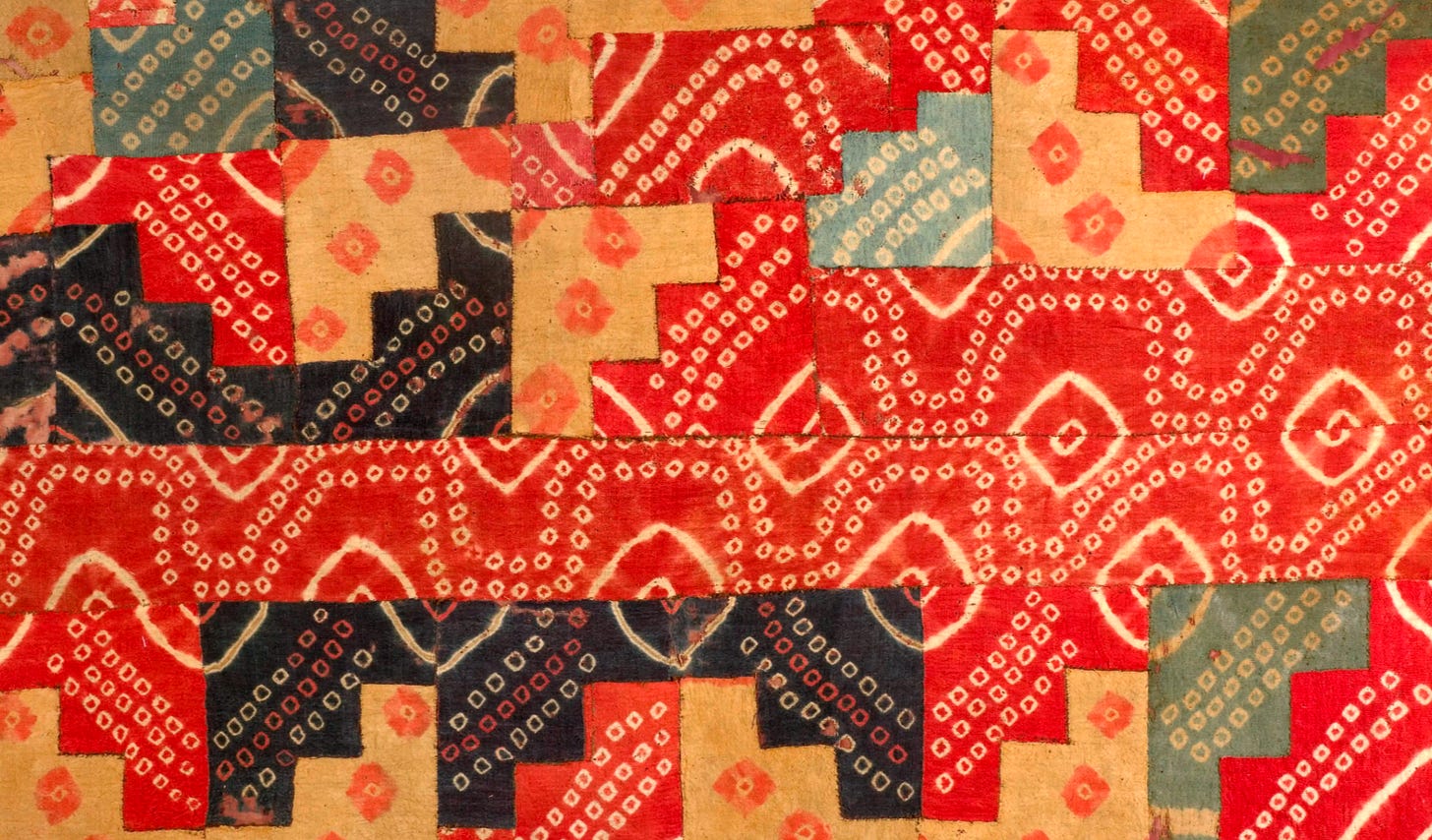

Art by Wari textile artists ca. 425–1100.

To read another Wayfare contributor’s perspective on The Great Feminization Hypothesis, read Sharlee Mullins Glenn’s Toward A Great Mutualization.

REFERENCES

Weigard A, Loviska AM, Beltz AM. Little evidence for sex or ovarian hormone influences on affective variability. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20925. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-00143-7

Samantha C. Paustian-Underdahl, Caitlin E. Smith Sockbeson, Alison V. Hall, Cynthia Saldanha Halliday. Gender and evaluations of leadership behaviors: A meta-analytic review of 50 years of research, The Leadership Quarterly, Volume 35, Issue 6, 2024.

Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of Hospital Mortality and Readmission Rates for Medicare Patients Treated by Male vs Female Physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Feb 1;177(2):206-213. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875. PMID: 27992617; PMCID: PMC5558155.

Blohm M, Sandblom G, Enochsson L, Österberg J. Differences in Cholecystectomy Outcomes and Operating Time Between Male and Female Surgeons in Sweden. JAMA Surg. 2023 Nov 1;158(11):1168-1175. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.3736. PMID: 37647076; PMCID: PMC10469280.

Heybati K, Chang A, Mohamud H, Satkunasivam R, Coburn N, Salles A, Tsugawa Y, Ikesu R, Saka N, Detsky AS, Ko DT, Ross H, Mamas MA, Jerath A, Wallis CJD. The association between physician sex and patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025 Jan 17;25(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s12913-025-12247-1. PMID: 39819673; PMCID: PMC11740500.

Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician Gender Effects in Medical Communication: A Meta-analytic Review. JAMA. 2002;288(6):756–764. doi:10.1001/jama.288.6.756.