The Architecture of Redemption

A Conversation with Anne Snyder

Anne Snyder is the editor-in-chief of the quarterly magazine, Comment: Public Theology for Common Good. Anne is also the host of the podcast, The Whole Person Revolution. In this conversation with In Good Faith host Steven Kapp Perry, Anne speaks about blending spiritual and secular efforts, the impact of public theology, and her personal journey to becoming a person of faith.

We hear so much about the loss of faith in institutions, whether the government or religion. What are the reasons for those losses of trust?

There are many reasons. In some of our largest, historically morally authoritative institutions, be they the office of the president or the Catholic church or large Protestant denominations, any large entity—also, more covenantal institutions like marriage and family—there is both an individual sense that has developed generationally that we don't quite know how to attach and stay attached.

We don't know how to stay committed. Commitment is an affront, to some degree, to the nature of change in reality and over a lifespan. It's also an affront to our own sense of agency and discernment. We live in a moment, I think generationally, where there's a move towards self-preservation. We are to be hyper-aware of the potential for toxicity in any given environment and protect ourselves.

The very same individuals who are bemoaning our individualistic society are also the ones, ironically, that are most on the side of looking out for yourself: be distrustful because you can get really hurt and abused. That's just become culturally accepted almost as conventional wisdom that I'd say has really gained steam in the last ten years.

I think everyday citizens watch leaders using those larger, classic institutions, not as stewards of their life over time or respecting a certain kind of ethos, but rather using them as platforms for self-glory. I think a lot of people have said, look, I've had it. If an institution is here to just prop up a leader who is invariably fallen and self-centered, then I'll have no more.

I do think there's a natural phenomenon where institutions by their very nature are a bit sclerotic. Whether you're talking about something like the state department or something very hierarchical like the Catholic church, they don't work very seamlessly with the pace of change of a more fluid, global technological era.

That's really interesting to hear you say. In one case, a lot of it is just the result of human frailty. People have failed in what they were appointed or elected to do. Also, this is really intriguing to me what you say about the speed of our modern communication and that it lags in institutions.

Yet, you could point to each of these institutions and point to great good that was done that could not have been accomplished individually. Because you do what you do, I think you must have hope for institutions and people.

I do. We're in such a quick age that's obsessed with immediate results and visibility. Institutions at their best support the background architecture for agile entrepreneurialism for redemptive responses to human pain.

So just as an example, I have the great joy of reporting on a fairly longstanding kind of collective impact effort trying to address very concerning upticks in gun violence throughout the city of Chicago.

It's called Together Chicago, and it was founded in 2016. They formalized into an actual nonprofit with quite a substantive staff, and I joined them yesterday for a staff meeting. It was interesting talking to a group that was 75% African American representing most of the neighborhoods throughout the city. It was very beautiful to see this cross-sector collaboration happening. They’re really united out of a sense that they're solving a major social problem from a combination of spiritual discernment and theological view, or in this case, a Christian theological view of the human person and how we're wired.

There is friendly soil here. For over 120 years now, there have been both liberal arts and other kinds of institutions that have had a very robust and intellectually rigorous approach to faith-seeking understanding that can actually play itself out and now eventually trickling down to a collaborative, hospitable reality.

This to me is institutions at their best. They're not out in front—they shouldn't need to be out in front. In my view, they should accept the quiet power that they have in either developing a human being's thinking and posture or sowing a community that can yield social change. I think if we all saw institutions less as just sort of serving our own needs and instead saw them as in the decades long, transgenerational business, we might all just rest a little easier and then have a little more energy to put our own elbows into trying to renew them and try to continue to shape the character of them to serve twenty-first-century complexity.

What kind of faith background did you come from? What was that process of claiming that for your own as you grew up?

I grew up overseas inside of a Christian family. The key data point is that my grandparents were Bible translators with an organization called Wycliffe, which kind of flowered in the 1930s and 1940s. They served in Peru, South America, in the jungle for many decades. My mother grew up there amidst Quechua indigenous tribal kids.

I was exposed to Christianity as a kid, very much as a beautiful, transcendent force. Growing up, I didn't actually understand Christianity as a Western thing. I understood it as a transcendent universal thing that. As an adult, I have had to study Christianity as it expresses itself in the West and then more peculiarly in the American context.

I wound up living in New England, which is a little like the Pacific Northwest. I went to a kind of an aggressively secular high school. I was part of just a classic youth group retreat that I chose to go to. I got exposed to this very real call towards a Christlike love, both for me and for the world. This happened outside of a high school context. I returned to that high school feeling, at once, like everything was enchanted, and everyone was connected, and everyone had a soul.

Feeling quite alienated religiously, and suddenly back in this school context, I wound up going to a college called Wheaton, which is west of Chicago. It is a Christian liberal arts school with this mantra regarding the integration of faith and learning.

It was so foreign to me. How can I study what I had understood in my fledgling Bible study path alongside pretty rigorous intellectual learning in high school? So, out of intrigue, I chose Wheaton, and suddenly I was exposed to all these different theological traditions within 2000 years of Christian social thought.

When you talk about public theology and how that can be good for a society, what do you mean exactly by public theology?

I should probably come up with a really comprehensive definition of public theology, but I define public theology as the study of God done by and for the public as it pertains to issues in the public square.

It's trying to understand, what does make people so distrustful? What are the hot issues that seem to lead to so much fracture? Are these fundamental differences?

I think in our particular case, Comment tries to be a journal that is open. We sort of bring in all truth is God's truth. We are rooted in what we call 2000 years of Christian social thought from the various streams, and that that's considered a living tradition and a living dialogue.

I'm encouraged with anything that can give hope to people who have, as you said, become so exhausted with extremes that they throw up their hands and say, “What can one person do?”

I'm wondering how working on Comment influences your faith life. And, on the flip side, how does your faith life influence your work on Comment? Can you separate those or see how they influence each other?

This work is hard. I feel like very much a steward. We're not trying to tell people what to think; we're trying to give them a reliable context within which to think and within which to continue to sow common ground and common good, whether they're in education or health care or policing or running a business or actually working inside the church, etc.

I take that responsibility very seriously. I don't feel nearly smart enough. It’s very prayerful work. Most of my prayers every day are, God, please help me see clearly and help me articulate in such a way that feels sufficiently foreign to modern reductive ears that they're enchanted again. So, yeah, the short answer is it has made my prayer life so much more frequent and desperate.

But you see God working at work in your work and the people you work with.

Yeah, I do. It’s a privilege. I didn't start this publication, but it's just one that is trying to shine a light and illuminate what God may be up to. I feel very lucky to be living in my calling.

Finally, I wonder what brings you joy in your faith life. Could you tell us about that?

I would say the two things that come to mind about joy in my faith life. The first is music. I grew up a musician, and I think anytime I hear Handel's “Messiah” or even like the “Sound of Silence” by Simon and Garfunkel, there is a sense of wonder for the beauty and majesty of a God. That's the first way at a very sensory level.

The second is really this experience yesterday being with a unlikely band of people on mission to try to be the hands and feet of Christ in their city. It's very real. They’re dealing with real pain, and real loss, and real trauma, yet they are united in prayer and laughter and tears. There were educational experts, economic development experts, police, community shepherds, etc. When I get to see communities of people that are inside the church and out on the street building God's kingdom on earth in some of the hardest hit places, something about that just fills me with hope. Being around faith-filled doers fills me with hope and the confidence that what I believe isn't just make believe.

On the In Good Faith podcast, host Steven Kapp Perry aims to build bridges of understanding between religious communities. In talking with believers of different faiths, he celebrates commonality and honors difference as they share their wisdom, sacred stories, faith journeys, and life experiences.

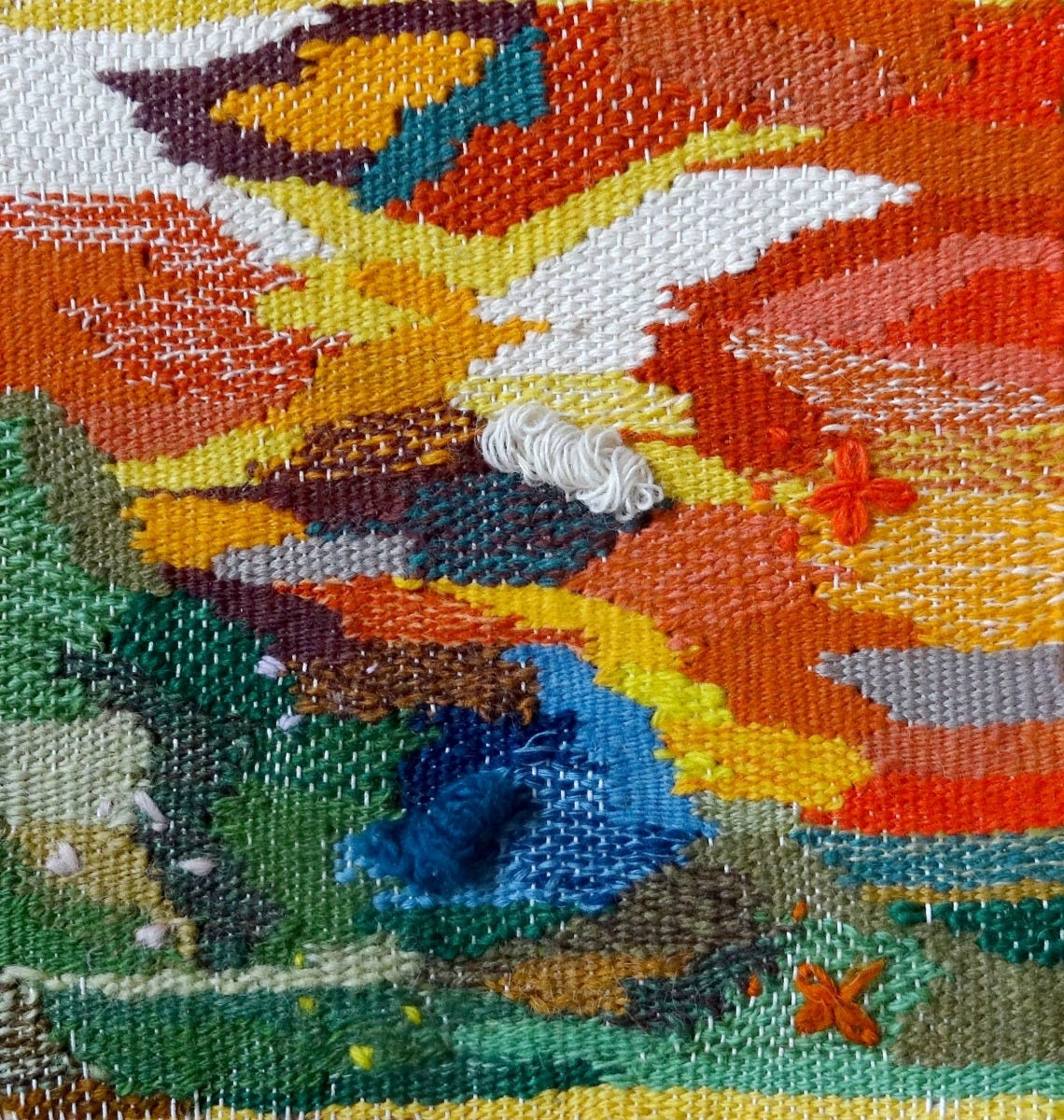

Artwork by Edite Paula-Vignere

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length. Listen to the full episode here or below