”I hope your mothers are not expecting you soon,” Yossel told Gimpel Peretz and Dudel Lewensztajn after their deacons quorum meeting one week, “because I am going to teach you how to fish.” They’d been excited, their minds filled up at once with images of fish flopping morbidly long after being pulled from the water, but they should have known that Yossel wouldn’t do such a thing on the Sabbath. He explained, instead, that in collecting fast offerings, they would be training to become fishers of men.

And yet, Gimpel observed grimly, he wouldn’t even give them hooks!

That first week they went it was oppressively hot. Gimpel was sweating more than it was healthy to do on a fast Sunday. He couldn’t understand, as they went from this street to that one, why God had not directed his people a little more rapidly toward some kind of payment app. This walking was barbaric.

Admittedly, though, it had an immediate impact on Gimpel’s spiritual education. As soon as he got home, he fetched down a volume of his father’s old copy of the Talmud: over the course of the afternoon, Gimpel had developed an interest in Jewish law. The halakha, he was coming to understand, had been created for a distinct purpose—but one adults these days simply didn’t appreciate. He had heard, for example, that the old rabbis had insisted on counting the number of steps one could be required to take on the Sabbath day.

They had surely been deacons when they were young.

Yes, there was something in Jewish law. A real history there, with implications for a modern life.

Dudel, for his part, didn’t mind collecting fast offerings. They didn’t have to do the whole ward: most members brought their fast offerings on their own, so he and Gimpel only had to stop by a few apartments. The walk between those few apartments was long, but they must be assigned to those families for a reason. He thought they were hand-picked—by Yossel Fischer or maybe by God, he didn’t know. It seemed like heaven, though, that sent him to the Cohen house.

Brother Cohen always seemed upset when they came by on their route—even more upset, that is, than his usual. He always paid fast offering. Quite generously, Dudel noted one week when Brother Cohen was too busy complaining about the nature of priesthood and the dangers of old traditions being neglected to use any discretion as he tucked money in the light blue fast offering envelope assigned to his address.

While Brother Cohen kvetched, Sister Cohen often threw in funny remarks, so that was nice. More precious than rubies, Dudel’s mother always said, was a woman with a nice, sharp tongue. He did not doubt his mother knew it.

But what Dudel really loved about going to the Cohens is that often, Zusa would be there with them. Sometimes, she would be sitting on the couch reading and he could just stare at her hair. And sometimes, she’d be looking out the window and he could wonder what she was noticing out there and what interesting thoughts she was having about it. And sometimes, she’d turn. And she’d smile. At him.

He wanted to say something to her. Something clever, like her grandmother (though of course not so cutting). Or something intelligent, or spiritual, or deep. His mouth always got dry inside, though, which was surprising since on Fast Sunday, it was dry to begin with. Everything he’d considered over the past month would slip right out of his melted mind when she smiled at him.

Why oh why was it only men Yossel wanted to make them fishers of!

After learning that the Talmud included very interesting passages about animals and which foods are disgusting, Gimpel had reached a long and intriguing passage about menstruation. There, however, the squat demon of ignorance stood in his way. He understood that the miracle of life was an ideal foundation for religious studies, but simply lacked the knowledge to follow the rabbis’ learned arguments about cloths and counting days. In addition to being mysterious, of course, he realized that his study of Talmud was not yet helping him get out of anything. Discouraged, he paused, at least temporarily, his careful study of Jewish law.

He had turned instead to Jewish history. His father had books on Karl Marx, Rosa Luxemburg, Leon Trotsky. It seemed to Gimpel that they had understood the true spirit of the Bible and what it meant when Moses slew the Egyptian. He tried to convince his father that the labor theory of value meant that Bishop Levy had no right to the fast offering, but his father had pointed out that the Bishop redistributed the money and that, therefore, helping with fast offerings was one of the most socialist things a young man could do in the Church.

Gimpel had changed tactics then. He argued that the deacons’ fast offering route was a form of child labor. He told his father about the stifling heat he and Dudel had to endure, the unreasonably long distances Yossel expected them to walk.

But his father only laughed and quoted Rosa Luxemburg: “Those who do not move do not notice their chains.” Service, he said, was good for you.

When Dudel was not collecting fast offerings from old people with girl-shaped granddaughters visiting their homes, he also enjoyed collecting fast offerings from old people without girl-shaped granddaughters in their homes. Before they would visit Henya Bittner—Henya the prophetess—Yossel would tell stories about how she talked with God. Dudel could believe it. Sometimes, when they brought her the sacrament, Henya’s eyes stayed closed for a moment after the prayer was done, and Dudel had a peculiar feeling: as if the last, long chord in the Beatles’ song “A Day in the Life” had fallen silent but left the air quivering.

When they came for fast offering, he kept his eyes open. While Henya asked about how they were doing, or what Gimpel had been reading lately, Dudel would look around for signs of anything God might have left behind after dropping by. Like maybe the Golden Plates or a Liahona…anything with curious workmanship, really. Even though his searches consistently came up empty, he never lost hope. One day, he was sure, he’d spot something rolled under a table or sitting on a shelf.

He could imagine what that might look like because of visits to his own great-grandfather, Israel Lewensztajn. Fast Sundays were the best time for Dudel to visit the man in his natural habitat. Everyone insisted that the family patriarch was too old to host guests, so the family always gathered elsewhere. But Israel’s apartment was filled with so many old, interesting things. Dudel appreciated the unhurried way his great-grandfather moved, his tendency to nod off while filling out the fast offering slip, and all the time these mannerisms gave the deacons to look around. Israel had empty tank shell casings he’d picked up in the woods. A towering grandfather clock with visible gears he still used to keep time, and a menorah his grandfather had used to keep time before that—one with carved symbols for each of the tribes of Israel.

Even Gimpel had to agree they were cool. If Dudel ever worked up the nerve to go sift through his great-grandfather’s back rooms, he wouldn’t be surprised to find trinkets that went further and further back into the past. A golem or two. The ark of the covenant. Maybe a lost tribe. Nothing would have shocked him.

It wasn’t quite the same as seeing Zusa, but it was still an exciting way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

After communism failed to deliver him from his burdens, Gimpel turned to capitalism instead. Was fast offering really efficient? Surely some entrepreneur could be paid to solve the problem of poverty in a way that didn’t involve Gimpel’s Sunday afternoons. And on some level, weren’t they actually doing a dis-service to whoever received fast offering money? They were robbing them of incentive to find work.

Why did Gimpel need to walk his feet raw when Adam Smith’s invisible hand could handle things so much better?

Oskar the miser might have listened to these arguments and advocated on the boys’ behalf, but they never collected fast offering from him. Apparently, he didn’t trust them not to skim a little off the top of his meager contribution. Instead, Gimpel had to make the case to his father, who was utterly unsympathetic to the philosophies that had won the Cold War. If Gimpel thought his feet were sore, Isaac Peretz suggested, he should see what fawning talk of capitalism in their home could do to his behind.

The only thing sweeter than seeing Zusa Cohen’s smile—and that only because it was Fast Sunday and because Gimple was right that they did walk quite a lot—was stopping by Zelda Gottstein’s. Truth be told, she was the reason the route took so long. After hours and hours without any food, which is very long for a deacon of any stomach size, there was nothing quite like the blintzes or babka Zelda Gottstein invariably offered them. What an offering to end a fast!

And then there was the coffee she poured herself to go with it. The coffee might have been the kids’ stuff most ward members drank, but he didn’t think so. Partly because it smelled a little more like heaven and a lot less like burnt wheat. And partly because Sister Gottstein always put a hand over it when she mumbled the blessing, like the polite thing was to show God clearly what you were asking him not to see.

One week Gimpel proposed to Dudel, conspiratorially, that they take Yossel and the Bible both a little more literally. What if, he suggested, they spread a great net out in the foyer, and pulled it tight when people came out? Then they would really be fishers of men.

Dudel was excited at first—Gimpel didn’t usually propose things that sounded quite so fun—but then he got suspicious. Was that all, he asked, or was there some kind of catch to this catch?

Well, Gimple admitted, there might be a little more to the plan. He thought they might charge a small fee for freeing people. Not in a priestcraft sort of way, of course. More like the money paid to redeem the first born son in temple days, or the afikomen at Passover, and then they’d collect plenty of fast offering and there would be no need to go off walking through the heat to learn some elusive virtues.

But Dudel said no. He liked going out in God’s name to smile at girls and see the strange interior of an old man’s apartment and eat sweets until he was stuffed. It was worth the walking, Dudel insisted. More than worth all the walking.

He hoped someday, he said dreamily, that they’d call him on a mission.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

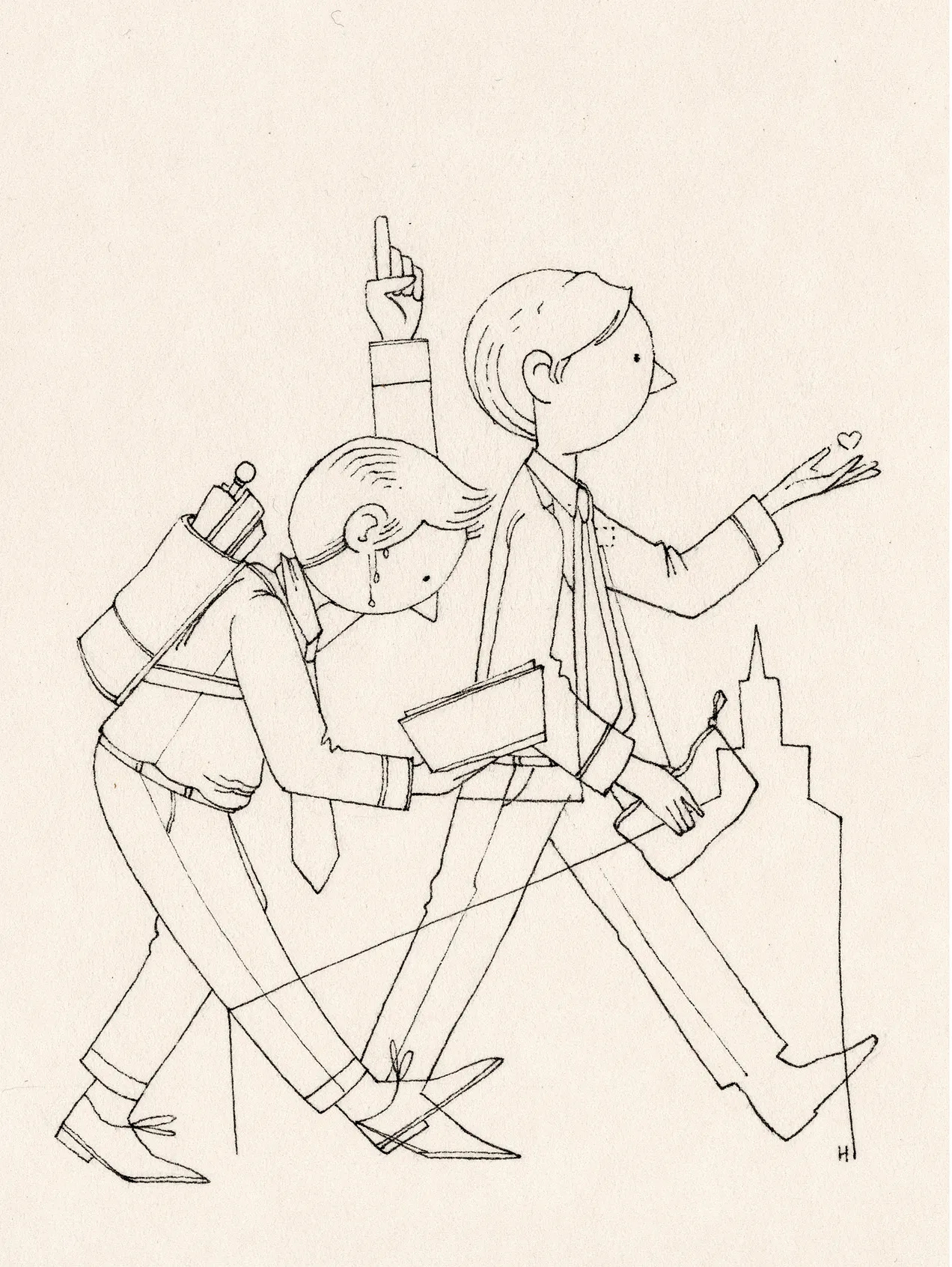

Artwork by David Habben.

To pre-order the complete Tales of the Chelm First Ward, click here.