In March 1829, Joseph Smith was finishing up his translation of the Book of Mormon, and received the first revelation in the voice of God directly foretelling a long-anticipated event. “I will establish my church, like unto the church which was taught by my disciples of old,” section 4 of the Book of Commandments (1833) reads. In the 1835 version, however (the same as the current edition), the verse refers to “the coming forth of my church out of the wilderness—clear as the moon, fair as the sun, and terrible as an army with banners” (D&C 5:14).

This language was also found in several contemporaneous publications, including Matthew Henry’s Bible Commentary (1706), Alexander Fraser’s Key to Prophecy (1795), and an 1830 edition of Alexander Campbell’s Millennial Harbinger—and all of them had borrowed the words from the seventeenth-century Quaker Samuel Fisher, who believed he was witnessing a restoration of the true church of Christ. Apparently, Joseph had read one of these sources, and the language resonated with him deeply enough that he included it in the next version of the revelation. The question is, why did it speak so deeply to him?

What is the significance of this shift from a church being “established” to a church “coming out of the wilderness”? What did Joseph understand by this reference to a church “coming out of the wilderness”? Revelation chapter 12, which Joseph said was an allegory of the “great apostasy,” describes a dragon besieging a primitive church, which then “fled into the wilderness.” The most telling part of the allegory for Joseph’s developing understanding is the subsequent description of what happens to that early church: it does not disappear, and it is not destroyed. While quiescent, scattered and existing at the margins and underground as it were, the church continues to be “nourished for a time,” in a state and condition “prepared of God.”

This vision of a church that persists as a continuous thread in the world’s history, consisting of devout souls and inspired voices, finds expression again and again in our scriptures and teachings, though it has often been overwhelmed by simplistic distortions and assumptions about truth monopolies. The Lord refers to “holy men [and women]” that are unknown to most of us but not to Him; Joseph himself taught of the need to seek out the best “words of wisdom” from our textual heritage, and to “gather all the good and true principles in the world,” from every religious tradition available to us.1 We should search for and be taught by these “voices in the wilderness,” not to corroborate what we believe but to enrich and expand and enlighten our limited perspectives.

We know—but it bears repeating—that the LDS church is one historical instantiation of a broader fullness. A narrow definition of that “fullness,” however, may have taken our minds in directions that poorly serve history and the church. The term deserves interrogation, and a broader, richer understanding of it may lead us toward new, more creative ways of conceiving of our institution and our personal engagement in God’s work.

The Abounding Church

Joseph’s 1829 revelation referred to a church that “was taught” anciently. This phrase carries different—more accurate and richer—significance than a reference to “an organization” that existed anciently (Article of Faith 8). If the essence of our religious claim refers primarily to the proper ecclesiastical structure, then we are but another instance of having the “forms” but not the “power of godliness.” Besides, other churches restored the office of apostles, and the Catholics also have the priests, bishops, and deacons that history confirms as the mainstays of early Christian organization. No one word (and certainly not “organization”) can do justice to the project, the work, the sensibility, the character, and the destiny to which God is leading us—the things that were “taught” by Jesus.

“Fullness” can’t simply mean “entirety” or “complete totality” as we so often take it to mean, or a modern prophet could hardly refer to a fullness that is still unfolding. Webster’s 1828 dictionary provides a different interpretation: a fullness is “the state of abounding.” Joseph formed a church in a greater “state of abounding.” I take it as a given that this abounding included a vibrant channel of communication with prophets and individuals, sacramental temple practices of eternal efficacy, and an ampler narrative of human origins and destinies. But that leaves room for a whole lot more abounding—more unfolding and enriching and expanding of heart and soul.

Some of that abounding can be encountered in the teachings of early Christian leaders. Gregory of Nyssa taught that God wanted to find a way to save everyone. Irenaeus proclaimed that we were sent to earth to learn through direct experience the value of the sweet and the cost of the bitter. Pelagius attacked infant guilt with the moral clarity of Moroni, and Origen knew we came from a prior plane of existence. Still, we Latter-day Saints must be about more than simply validating strands of the multiple Christianities of the first centuries. We must see our project as an endlessly creative one. No Christian theologian is more sensitive than David Bentley Hart to what Christianity has lost—nor more impatient for repair. But he warns us eloquently of the dangers of a backward looking form of restoration:

The configurations of the old Christian order are irrecoverable now, and in many ways that is for the best. But the possibilities of another, perhaps radically different Christian social vision remain to be explored and cultivated. Chastened by all that has been learned from the failures of the past, disencumbered of both nostalgia and resentment, eager to gather up all the most useful and beautiful and ennobling fragments of the ruined edifice of the old Christendom so as to integrate them into better patterns, Christians might yet be able to imagine an altogether different social and cultural synthesis. Christian thought can always return to the apocalyptic novum of the event of the Gospel in its first beginning and, drawing renewed vigor from that inexhaustible source, imagine new expressions of the love it is supposed to proclaim to the world, and new ways beyond the impasses of the present.

The Creative Church

We invite several perils by associating "restoration" and "fullness" with past and total incarnations. The words presume a fixity, a stasis, an ahistorical set of practices and principles sufficient for all times and conditions—a theological universe, in sum, that is static, sterile and ultimately, stifling. Creativity, novelty, growth, adaptation, adventure, and exuberance find little place in such a programmatic vision. Instead of a dynamic process of unfolding spiritual truths, a process that we participate in with God, connotations of the word “fullness” can suggest simply reassembling puzzle pieces already present into a bordered whole.

I see a different God in Joseph Smith’s revelations, one more similar to the God of Genesis, who says, “Let us create.” One commentator writes, “The ‘let us’ language refers to an image of God as a consultant of other divine beings…. Those who are not God are called to participate in this act of creation…. The ‘let us make’ thus implicitly extends to human beings, for they are created in the image of one who chooses to create in a way that shares power with others.”2

What John said of God’s progeny I take to be true of the cosmos: “It doth not yet appear what we shall be.” Not because the veil is drawn, but because the future does not yet exist. Nikolai Berdyaev goes so far as to say it is creativity itself that generates a future:

It is usually said that creativeness needs the perspective of the future and presupposes changes that take place in time. In truth, it would be more correct to say that movement, change, creativeness give rise to time. Thus we see that time has a double nature. It is the source both of hope and of pain and torture….The products of creativeness remain in time, but the creative act itself, the creative flight, communes with eternity. Every creative act of ours in relation to other people—an act of love, of pity, of help, of peacemaking—not merely has a future but is eternal.3

This may sound far afield from the simple question, what does a church coming out of the wilderness look like? Like any emergent thing, the answer cannot be fully known. As we reach out with passionate curiosity and generosity to assimilate the fruits of those who have communed with God and been vessels of wisdom and grace, the gospel—and the church—will become ever more “abounding,” ever more “abundant” in, and ever more constitutive of, beauty and goodness and other values we may not yet know how to speak.

The Invisible Church

Modern scripture provides us with the resources for rethinking fullness into more expansive and open-ended domains. Though the idea seems to have faded from LDS consciousness, Joseph frequently employed language that evoked the historic idea of the “invisible church,” constituted by those who in every age participate in the Christly work of healing the wounded, building community, and striving to emulate God. Modern scripture also refers to “the church of the firstborn,” “the general assembly and church of Enoch,” and a church “of the Lamb of God” that Nephi saw. These may intersect but do not consist of any one institution. The great mystic Jacob Boehme called it “die Kirche ohne Mauer,” the church without walls. Most often, Saints call it Zion, sometimes forgetting that it may be a timeless order of the godly, as much as a present work in progress.

In addition to the friendship, solace, and tireless servants of the good that we find in our distinctive LDS wards, we also find kinship and profound connection—and an equally real and vibrant community—among those “who will have him to be their God.” My hope is that by reconsidering the concept of “fullness” we may take it more seriously and ambitiously. As individuals, we need a vision that leads us to a more transformative and exciting activity than simply acting as spiritual magpies, or like Jonathan Swift’s energetic bees, flitting from flower to flower assembling the makings of “sweetness and light.” What I mean is forging a disposition toward openness, recognizing and feeling a sacred solidarity with other seekers of godliness, and having our faith enriched and reshaped by the humility of “holy envy.” That has certainly been my case in the profound depths of God’s love I experienced reading Julian of Norwich, a reframed understanding of justice and authority provoked by Nikolai Berdyaev’s work, and a dawning awareness of how the atonement draws us to Christ by contemplating Abelard’s critique of medieval theologies of redemption. Dorothy Day’s biography leaves me restless and dissatisfied with the chasm between my own faith commitments and a suffering world waiting upon action.

I believe these aspirations are in harmony with recent shifts in the way we invoke and describe Zion, as rhetoric shifts to more inclusive language. This is even evident in our architecture. Early Utah temples, manifest embodiments of insularity and political defiance in their towers and crenellations, have given way to more subtle expressions of spiritual yearning. In like fashion, Zion seems to me to be assuming a more inviting and inclusive ideal, involving good people of all races, cultures, and faith traditions. The “invisible church” expands that generosity of vision across time as well as space. And Latter-day Saints see this ideal as within the reach of human striving. Early Latter-day Saints tended toward pre-millennialist conceptions of a fierce God, interposing himself in human history to launch with dramatic form a sudden era of peace. More recent rhetoric places the burden of the transformation on our own shoulders, shoulders that are understood to include “those who will have him to be their God.”4

And if we are successful, we may be surprised by what is already implicit, rather than anxiously awaiting, in that metamorphosis: another type of “fullness” of the gospel. As Berdyaev wrote, there must come a point when “the dream of another and better life [will disappear], since it will have been realized.” But that is a life that can only be realized in community. At that day, in a picture perhaps both symbolic and literal, “Then shalt thou and all thy city meet them there, and we will receive them into our bosom, and they shall see us; and we will fall upon their necks, and they shall fall upon our necks, and we will kiss each other; And there shall be mine abode.”5

Terryl Givens is Senior Research Fellow at the Maxwell Institute and author and co-author of many books, including Wrestling the Angel and The God Who Weeps.

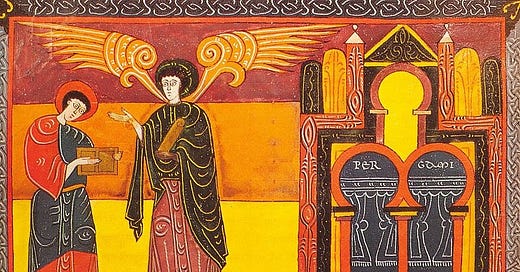

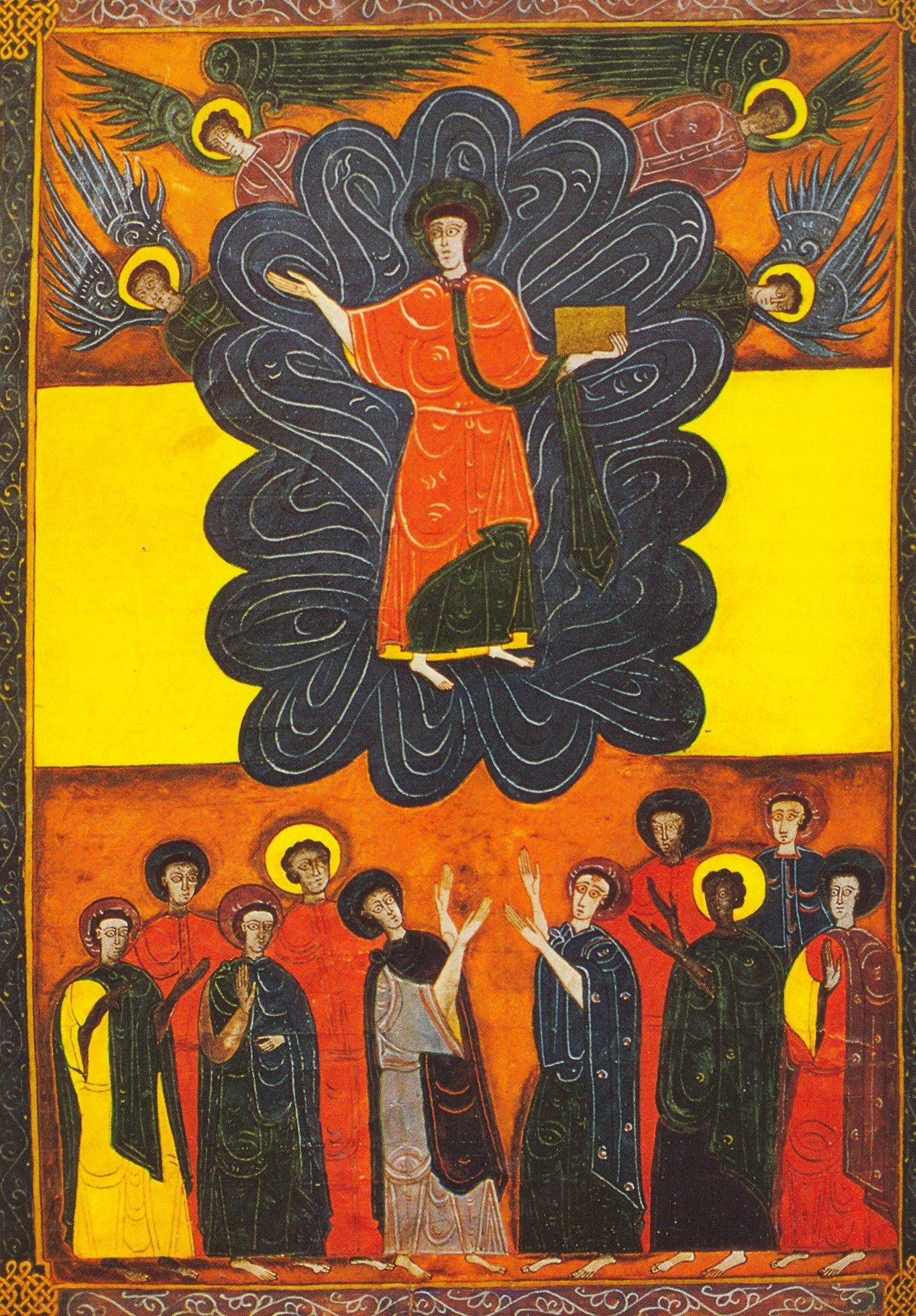

Art by Facundus.

To receive each new Terryl Givens Wayfare essay by email, first make sure to subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling With Angels."

I’m preparing a Mother’s Day talk and using the section on a creative church as the jumping off point. “Let us create”… an invitation from God to partner with him. That we have the mindset of creating instead of consuming… thank you for a beautiful essay, so inspiring.