Temples of Flesh and Blood

What the Menstrual Cycle Teaches About the Nature of God

At the beginning of their mortal journey, God told Eve about the pangs of childbirth and informed Adam that the ground was cursed for his sake, requiring him to work to have food. Not knowing why, Adam obeyed the commandment to sacrifice the first of the animals he had worked hard to raise (Moses 4:22–25). I imagine around the same time, Eve was experiencing menstruation, a biological indicator that she could bring forth new life. Of these two forms of blood shedding, the angel explained one represented Christ’s sacrifice (Moses 5:6–7). I can’t help but wonder if the other symbolizes the same.

While there is no scripture that explicitly links menstruation with the atonement, Moses 6:63 teaches that all things are created to bear record of Christ. During his earthly ministry Jesus referenced childbirth as a metaphor to teach his disciples about his imminent atonement (John 16:21). I have not yet given birth, as I one day hope to. But I have had a menstrual cycle each month since I was eleven years old. It has taught me in ways that words cannot.

Bodies are powerful teachers, but their knowledge is not easily shared as the embodied experience is unique to each person. My goal in this essay is to point back to the body as a teacher of truth by sharing some of what my body has taught me about the atonement of Jesus Christ. My hope is that readers reflect on what their body is teaching them.

I was taught that receiving a body is an essential part of becoming like my Heavenly Mother. I believe one reason the body is so vital to spiritual development is because it necessitates vulnerability (Jehovah’s plan) over control (Lucifer’s plan). The most poignant way my body has taught me this is through menstruation, a blood shedding that consistently reminds me of Christ’s atonement.

Temple of Blood

Each month my lower abdomen and back ache as my internal life-giving organ constricts itself. The uterus has spent about twenty-eight days preparing a rich lining with the necessities to nourish a new life. Without a new life to sustain, the uterus contracts and sheds the lining, causing me to bleed for about seven days.

Many cultures practice rituals around menstruation. Some have undoubtedly been oppressive patriarchal interpretations and implementations of menstrual rituals. It would be foolish and cruel to discount this fact. However, it would be equally foolish to dismiss menstrual rituals that give deep meaning to the women who practice them.

The modern mindset often views rituals as silly at best and harmful at worst. However, done well, ritual is beautiful, spiritual, and powerful. Modern understanding sees truth as empirical fact that can be objectively transmitted from one person to another. It often negates the possibility of learning truth from within oneself. Rituals teach truths that cannot always be put into words, but the truths are full of meaning to the one who finds them.

In her work, The Battle for God, Karen Armstrong describes two general approaches to understanding and learning truth, which she calls mythos and logos. Logos is the primary approach to knowledge in the twenty-first century. It is the rational, logical, pragmatic and scientific view of the world. Logos looks ahead and tries to be in charge of the environment through discovery and innovation.

As Armstrong describes, in the ancient world, mythos was the predominant mindset toward truth. Today the word myth means a falsehood, but anciently, mythos meant a story that may not be literally true but teaches a truth. Mythos was concerned with the timeless and constant aspects of existence. It looked back to origins and the deepest levels of the mind. Myth was not meant to be practical; it was meant to convey meaning. Through myth, people created context for their life and directed their attention to the universal and eternal. Myth became a reality to people when it was embodied in cult, ritual, and ceremony. For most people today, fables and fairytales are the most recognizable expressions of mythos. They are stories that are not literally true but usually teach a truth. The tortoise and the hare story may not have happened, but from it, we learn that slow and steady wins the race.

The Latter-day Saint form of mythos is temple worship. It can be uncomfortable or even frightening for those who have only been exposed to logos ways of being. Through no fault of their own, many members feel betrayed that their most sacred religious experience is unsettling. Some have described the temple ceremony as “cultish,” using the term in its colloquial sense of nefarious and deceptive. Perhaps it is our unfamiliarity with mythos in our modern world that causes this discomfort. The original meaning of cult was a select group of people who perform rituals as part of their worship of a particular deity.

The temple is a cultic ritual that tells a myth rich in symbolism. The ritualized myth can teach practitioners about life and the eternal. In the temple, Latter-day Saints embody the stories of creation, the fall, and atonement. LDS canon has seven accounts of the creation narrative and four of the myth of Adam and Eve. These stories are our mythos. They are meant to teach us about universal and eternal truths, and they do so through symbolism. In the temple, we relive the story of Adam and Eve as if we were them. Characters in the narrative are not meant to depict what literally happened, but to be symbols of how life works. Because it is symbolic, it can teach different people different truths according to what they need to understand for their own lives.

While in the temple one day, I understood something new through the narrative. In my own personal study I had learned that the Hebrew word אָדָם, translated as Adam, means “earthling” or “humankind.” The Hebrew word חַוָּה, or Eve, means “life,” specifically “divine life;” that is why she is the mother of all living. As I watched the narrative, I thought of how the natural man in all of us, or the Adam, chooses to stay in paradise where there is no growth because there is no discomfort. The divine life in all of us, or the Eve, chooses to receive knowledge of good and evil, even though it causes pain and suffering, because it is also the only way to find joy.

I believe our Heavenly Parents have conflicting emotions regarding our mortality. They do not want us to be separated from them or to experience the pain that is part and parcel with mortality—thus their command to not eat the fruit. But their other, more important desire is for us to grow and become all that they are. Mortality, with all its pains, is a necessary stepping stone in that growth. And so with their conflicting wants comes the conflicting commandment to multiply and replenish the earth. As Lehi teaches in 2 Nephi chapter 2, both of these commandments could not be kept, so God introduced agency into the equation with the phrase “nevertheless, thou may choose for thyself” (Moses 3:17). That day in the temple, I learned through symbolism that the divine life in me could lovingly persuade the natural man in me to embrace the commandment to grow. The growth may cause pain, which my Heavenly Parents don’t want, and which my Savior feels with me, but we can all recognize it as beautiful and worthwhile from an eternal perspective. God’s infinite love for us requires that they allow us to be free agents to choose for ourselves what we want most.

From a natural man perspective, the pain and mess of menstruation and childbirth seems like a curse. However, from the divine life perspective, they are beautiful gifts, in part because they are not necessarily always pleasurable. Eve knew that it would be better for us to pass through sorrow that we might learn the difference between good and evil (Moses 5:11).

A Microcosm of the Macrocosm

The creation narrative in Genesis 1 portrays the ordering of chaos. Boundaries are formed between the light and the darkness, water above and water below, dry land and sea, vegetation and animals. Lastly, humans are formed as separate from the rest of creation, being in “God’s image.” In Judaism, demarcation sets apart the sacred and profane, which is why there are rules regulating all aspects of life: They are the boundaries that allow creation.

Ancient Israelites often understood ritual violations as we view physical ailments today and treated them similarly: by going to someone set apart (doctor) to prescribe a solution (medicine). As scholar John Markowski argues, impurity in ancient Israel was intended to be the language of cult and ritual; not necessarily a signal of moral disgust.

One of the ritualistic boundaries in Judaism is the Niddah, a period of seven days, starting with the first day of bleeding of a woman’s menstrual cycle. The amount of time blood flows did not prescribe the length of the Niddah, since that could differ among women. Niddah is always seven days, the number symbolizing complete, perfect holiness in Hebrew. Since the length of blood flow did not dictate the Niddah, it may be safe to conclude that the separation of a woman from others during this time was not based on repulsion of menstrual discharge. Rather, the female cycle structured time in relation to the sacred.

During the Niddah, a woman is not herself ritually impure, but she can cause others to be. This gives her reason to withdraw and lay aside her work for a period of time. After her seven days, a woman ends the Niddah by going to the mikvah, or ritual bath. In the modern context, when Jewish women go to their nearest mikvah there is a restroom set aside for them to cleanse and prepare. They may shave, exfoliate, remove nail polish, comb their hair, bathe, and shower beforehand. Then they will go to the mikvah to fully immerse themselves three times while reciting prayers. These rituals, both the Niddah and the mikvah, create a boundary between the mundane work of life, and the sacred time for a woman to reflect, repent, and restore and cleanse her body. Time set aside for rest allows more creation when it is time to work again. In this way, the body becomes a sacred teacher and a conduit through which we can act out the mundane and the sacred, deepening our understanding of truths through physical embodiment.

Most modern women can, and regularly do, continue to go about their regular life while menstruating. But I’d guess most women would also gladly take the opportunity to rest during this time. It is not a question of women’s capability or fragility but of what is best for a woman. Tending to a body’s differing needs at different times of her cycle creates more capacity overall.

Temple of Flesh

I have holy envy for the Niddah, but I recognize that there are many ways I, too, can learn from my body. While sitting in sacrament meeting one day, the thought occurred to me: The body is the only stewardship everyone has that is non-transferable. I ruminated on that idea for a while, pondering its implications. I thought about how care for or attempts to control the body have direct consequences for the steward. Meaning, the body is a teacher and when we ignore its teachings, it impacts us and our lived experience. My body has repeatedly tried to teach me to embrace vulnerability and care rather than security in control. In other words, the body teaches how to become like the Gods. That is why it is a temple.

Controlling the body is an illusion that assumes we have power over what we do not. As long as we fixate on changing what we cannot, we will be miserable. And so for many, their temple becomes their damnation. In efforts to control aging, pain, looks, and so on, we fill our bodies with poison. Sometimes literally, but always figuratively. The line between care (tending to our vulnerabilities) and control is not always clear since the same action could be either, depending on intention. But by the fruit they bear time will tell which is which—if we have the ears to hear and the eyes to see.

All humans are vulnerable, and in our vulnerability we have two choices to make: Remain so, even if it hurts, or seek a false sense of security in control. This security will ultimately fail because it is based on a lie. Remaining in vulnerability, however, is choosing to remain in truth. This is what our Heavenly Parents have mastered. They chose to love and trust us rather than control us, as Lucifer wanted. In so doing they made themselves vulnerable.

Remaining in vulnerability is what my body asks of me, and when I listen, I always feel more whole. This is more prominent during menstruation as my hormones change, my body slows, and more sleep is required. The change of pace gives me time to reflect. During this time I think about another who bled so that others could live. I feel gratitude for the aches that remind me of the one who felt every pain. I find comfort in the arms of my husband, who cannot take the pain away but can hold me like an angel once held Christ.

A Vulnerable God

To be human is to have needs To have needs is to be vulnerable Humans are created in the image of God Ergo, God is vulnerable. How can a God be vulnerable? God loves Their children, And control comes from fear, not love, So God gave Their children agency. God’s children hate their own blood And use their agency to kill This makes God weep. This makes God vulnerable. When we are vulnerable As God is We embrace part of our divine heritage. But how often the natural man chooses security over openness Control because of fear Being impenetrable to suffering And impenetrable to God, who suffers with us. And yet suffering persists Ignoring it does not make it go away It makes it go unconsecrated. What vulnerabilities Do you let go untouched by God?

Abigail Eve Harper’s lifework is to create beauty and so she practices what she finds beautiful: vulnerability, creativity, and reconciliation. She studied intercultural peacebuilding and psychology at BYU-Hawaii and is earning her masters in religious studies at Drew University.

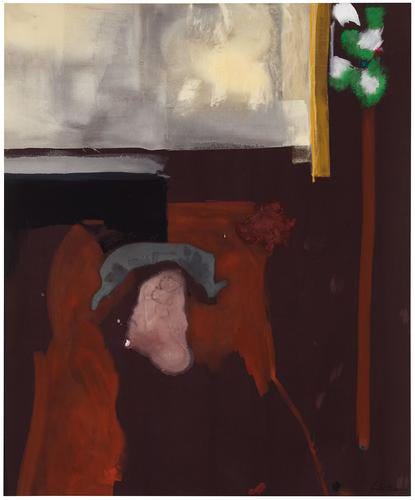

Art by Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011).