Introduction to Tales of the Chelm First Ward

After it was announced that the old visiting teaching and home teaching programs would be replaced with a new program called ministering, which God had sent the faithful to reduce both guilt and bus fare, Fruma Selig and President Gronam met to disagree about how to make new assignments. The meeting was a historic occasion. Previously, each had disagreed about how to make assignments only with their own counselors. This was the first time they were to sit down and disagree with each other directly: now that there was official permission for arrangements such as couples being assigned together, Bishop Levy had wanted them to think through new approaches for the whole ward.

Both presidents were old enough to know that even the most cosmetic of changes can create a disastrous mental load. They understood that freedom and flexibility, however appealing in theory, are, in practice, remarkably prone to breakdown. And so it was, together, that they tried to come up with a new blanket rule for creating assignments—something that could give the same reassuring thoughtlessness of time-worn habit.

They started by studying the issue out in their minds, waiting for a spark of divine inspiration. But when it’s dark, even the smallest flash of an idea can feel like lightning from heaven. As he pondered, for example, President Gronam felt a rush of intelligence filling the narrow confines of his head and quickly proposed a system for assigning pairs based on beard length. What better way could there be, he said, to yoke the wise and experienced easily to their peers.

Fruma Selig objected. Beard length, she said, was hardly a reliable measure of experience.

President Gronam defended that principle from the scriptures. He cited 2 Samuel 10:5—Tarry at Jericho, until your beards be grown—and the 133rd Psalm—How pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity! Like precious ointment that ran down the beard.

But Fruma did not relent. “Whatever system we choose,” she said, “will need to be created with the Church’s women as well as its men in mind.”

President Gronam could hardly believe his ears. Why, a rule like that would overturn generations of precedent! “I don’t think the brethren meant this change to be so drastic,” he grumbled. But Fruma Selig held firm. And after some time, President Gronam conceded that beard length might fall short of her unorthodox standard.

With that first idea discarded, it was time to let their minds’ wheels turn again. This time, it was Fruma’s that ran into something and threw off a spark. She proposed a system in which, in the timely spirit of simplification, everyone served as a minister to the person who lived closest to them. But though he knew many would welcome such a proposal, President Gronam resisted it. “Every person on earth lives in their own skin,” he observed, “and we are therefore all closest to ourselves. Surely you can see that assigning people as their own ministers is a bad idea,” he added. “Just think of the personality conflicts!”

Fruma Selig sighed. “That is true enough,” she admitted. “Some might make the adjustment with time, but Mirele Schwartz would always be far too harsh.”

Having been failed by inspiration, President Gronam turned to common sense. Since they and their counselors needed to conduct ministering interviews in any case, he argued, they could simply assign themselves as ministers to the entire ward and kill a whole flock of birds, so to speak, with one stone. Fruma Selig, however, was concerned that in their interviews they would have nothing to talk about. “Besides,” she added, “we would only be interviewing the parents: who would minister to the children?”

Both of them let that question sink in a moment. “Now that,” said President Gronam said, “may be just the answer we are looking for.”

Sometimes God sends inspiration in pieces and it takes a council to put those pieces together. In this case, the two presidents decided to build off Fruma Selig’s proposal to have people minister close to home and President Gronam’s realization that children were the key to the entire problem by assigning parents to minister to their own children. Nothing, they felt, could be more home-centered. Not only that, it would make it easy for everyone to know (and even remember) who their assigned ministers were. In all President Gronam’s years of experience with home teaching, such a thing had never happened. Surely, this was the answer.

Would it work for all ward members? Yes, on that count the system would be marvelous. All had been children at one point, after all, so everyone would have an assigned ministering brother and sister somewhere. Not all members were parents, of course, so some would no longer be assigned to minister. But if Chelm’s new system added guilt by accident where other Church programs already heaped it, that could hardly be counted as a concern. All things considered, the idea felt almost too good to be true. President Gronam and Fruma Selig concluded their meeting with an agreement to announce it the very next week.

*

Ward members greeted the idea, as always, not by responding to its individual merits but through their habitual posture toward any communication from authority figures in the Church. Mirele Schwartz preemptively bore testimony of the truth of the scheme. Oskar the Miser questioned the motives of President Gronam and Bishop Levy, the intelligence of Church authorities in Frankfurt and Salt Lake, the wisdom of the angels in heaven, and the competence of God. As soon as they were told about the new ministering assignments, others reflexively nodded righteously, rolled their eyes, or shrugged—all as the force of habit dictated.

After a month, though, ward members’ reactions no longer aligned with their reflexes. Some who prided themselves on their gift for discontent found that they loved the system. Some who prided themselves on their particularity and zeal could almost admit, if pressed, that they did not care for it.

There were no shortage of stories for Presidents Selig and Gronam to repeat when they wished, respectively, to encourage sisters in their duty or scold brothers for their faithlessness. Zalman the Learned, for example, had reported that since the introduction of the new system, his children had listened more attentively than ever during the family’s monthly half-hour of scripture study. Clever Gretele also had only good to say about the system: her husband Heshel, she observed, was spending far more time at home and far less time hopelessly lost searching for new routes by which to conduct his visits. And 97-year-old Israel Lewensztajn broke four years of silence during elders’ quorum to relate how his parents had started visiting him in dreams while he slept in sacrament meeting. “It’s been very pleasant,” he said. “I never got along with my father when he was alive, but nothing mellows a man quite like death.”

Other members’ reactions were of a kind that tended not to be shared in Relief Society or Quorum meetings. Bishop Levy had his hands full. He was counseling regularly now with the Cohens, who were otherwise content with their lives’ portion of unhappiness but desperately missed the assigned companions they’d long relied on as an outlet. The otherwise unflappable fatalism of Lazar the Blind Beggar was sorely tested by the loss of his old home teacher, Menachem Menashe, who had read the scriptures to him and given him, in their long and wandering visits, tomes’ worth of spoken commentary. Far more than the pickles and fish Menashe used to bring, it was the loss of those hours that made Lazar feel poorer. Even Belka Fisher made an appointment with the Bishop to tearfully admit that while she had always done her best to do the bare minimum in every assignment given to her, not even she could keep herself from asking her children how they were doing more than the ministering program’s mandate of once every three months.

His heart breaking for the Belka Fischers of the ward, for Lazar the blind beggar, and (after sessions with the Cohens) especially for himself, Bishop Levy’s resolve to sustain the officers of his ward in their decisions finally broke. He called in President Gronam and President Selig and begged them to find another way.

Though they could not understand the bleary-eyed bishop’s tears, Fruma Selig and President Gronam reluctantly agreed to return to the proverbial (as well as a literal) drawing board.

*

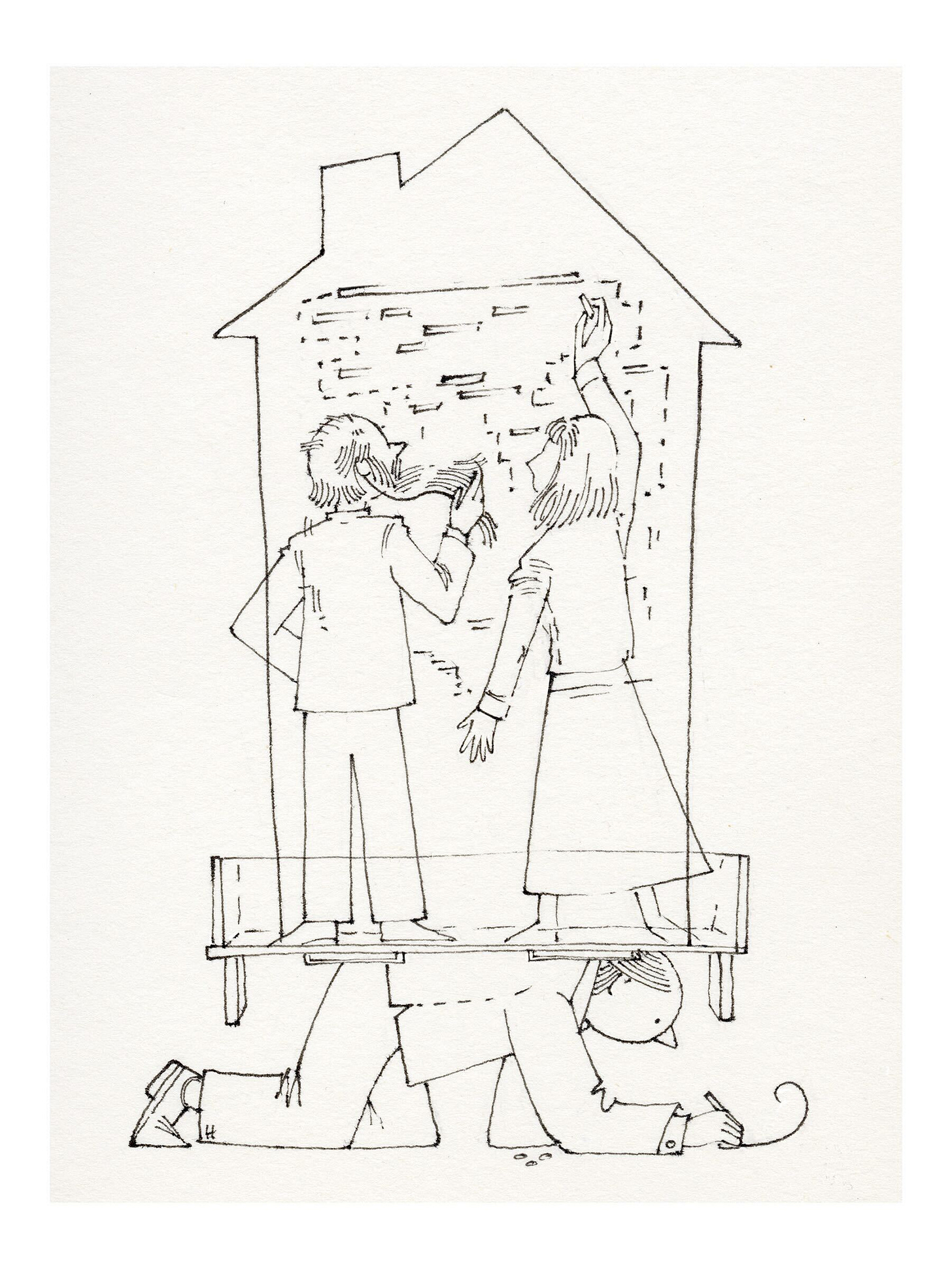

If inspiration comes by knocking at the door, President Gronam and Fruma Selig were prepared to use a battering ram. They printed out lists of households. They brought food. They pulled up a chalkboard and sharpened several pieces of chalk. They were prepared to throw ideas at the Lord until he confirmed one for them just to bring the meeting to an end.

The first option they considered was simply reversing their system to have children minister to their parents. Mathematically, though, that was a challenge. Parents typically came in ones or twos. The number of children in a household felt almost random. Some poor people would be hopelessly outnumbered by literal ministering brothers and sisters. Other ward members would be ministered to by no one at all.

With the household-based system undone, they next considered assigning people to their next-door neighbors. A simple review of the membership list, however, revealed that such a system resulted in an interpersonal nightmare. A nightmare which, unfortunately, would lack the justification of inflicting uniform misery. Truly, it was as if someone had set out to compile the ward’s best and worst relationships into a single, headache-inducing list! It was a good thing that Jesus had answered the question, “who is my neighbor?” with a long parable, because if he had said, “the person who lives closest to you,” the ward would have some real troubles.

They tried sorting their list through other objective traits. Age order resulted in low-mobility companionships like Israel Lewenstajn and Henya the Prophetess, as well as low-focus companionships, like Chava Gottstein-Kleiner and Golda Fischer. Conversion order looked a little nice at first, but broke down in the recent years, as baptism date began to clump young people together.

Considering the difficulty of natural systems of order, President Gronam gave a strong scriptural argument (founded in Proverbs 18:18 but also citing precedent from Acts to 1 Nephi to Joshua and even Leviticus) for casting lots. Few concepts had such long scriptural support as randomness. But Fruma Selig, who felt quite attached to the latter-day prophets, felt a duty to caution against even the appearance of gambling.

“This should not be so difficult,” President Gronam exclaimed after hours of mapping, planning, discussion, and debate. “After thousands of years of history, how has a system that takes into account both proximity and tolerability never been designed?”

Fruma Selig clapped her hands as inspiration came to her. “That’s it!” she said. “It should have been obvious—only we’ve been looking at the wrong map.” She took the map of the ward down from the board at once and drew a succession of rectangles in its place. Long, thin rectangles with a gap and then a smaller squarish shape at the center of the top.

“Of course!” said President Gronam. “Sacrament seating!”

Fruma Selig beamed. “They already pray together, sing together, and share a message. If we can get them to shake hands and say Shalom to each other during the meeting, ministering will be done!”

From memory, they compiled a list of who sat where. As they had suspected, people who couldn’t stand each other also didn’t sit together (siblings and spouses alone excepted) and after a little discussion over who should turn to the person beside them and who should look forward or behind, they were ready to enter the assignments into the meetinghouse’s aging computer and print off assignment slips for everyone in the ward.

The next week, President Gronam watched in self-vindicating satisfaction as ministering unfolded beautifully before his eyes. People chose their own degree of involvement: Belka Fischer barely making eye contact down her pew, while Lazar the Blind Beggar and Menchem Menasche lingered even after Zalman the Learned, whose week it was to teach Sunday school, had started the lesson.

“How clever we are,” he said to Fruma Selig after the meeting was done.

“Clever enough to be inspired,” she replied.

He sighed in satisfaction. “This is a system that could last a lifetime.”

*

The next week, President Gronam came uncharacteristically early to watch the beautiful machine in motion. To his delight, he found the pew just behind the chapel entrance open. He had always found the pew enticing: it belonged to the back section, where he felt so comfortable and at home, but had the beckoning softness of a padded bench, not the metallic cold of the hard chair that was his traditional place in services. And the leg room! President Gronam had often watched Lemel with envy as the man folded back his legs to let the deacons, Gimpel and Dudel, pass during the sacrament and then as he stretched them out again in open luxury for the rest of the meeting.

Well? Lemel was not here yet, and President Gronam was. He took the pew he’d always coveted from a distance after ducking into meetings just as they began.

When he arrived (not a minute later), the sheer force of habit almost drove Lemel into President Gronam’s lap. But Tzipa called out to him just in time and the two of them went to find another place to sit. Instead of slinking to President Gronam’s usual corner of the back, however, they moved to the rearmost pew in the front section. The one President Gronam could only think of as the Fischers’ bench. The Fischers, apparently, liked to sit at the back of the front and so moved to the Schwartzes’ bench on the other side. And so it went, on and on, President Gronam realizing with horror that he had caused a chain reaction. By the time Leah Kantor walked up to conduct the opening hymn, the only one who seemed to be in her usual spot was Zelda Gottstein. Out in the foyer.

It was a disaster. An unmitigated disaster. Like a Schroedinger’s cat sentenced to death by a careless act of observation, the beautiful ministering system had been brought down by one ill-considered, covetous choice. Truly, this was the day for which God had given the tenth commandment.

President Gronam tried to enjoy the leg room on his pew, but he could take no comfort in it. He sighed instead, took out a piece of paper and a pencil, sketched out the week’s seating configuration, and left just after the sacrament had been passed. He needed to enter new assignments into the ward’s aging computer before it was too late.

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

Artwork by David Habben.