Summoned by Beauty

A Researcher's Unexpected Encounters with Tangible Transcendence

We tend to think of beauty as superficial—the stuff of fashion ads and curated selfies—or worse, as a tool reinforcing prejudice and oppression. But beauty isn’t trivial; it is a summons, inviting us into deeper connection, understanding, and even moral action. To serve us rightly, beauty must always walk hand-in-hand with truth, goodness, and justice.

My earliest encounters with beauty were shaped by the Hindu temple I visited as a child in Oman. I was the child of Indian guest workers in the Arabian Gulf, and still carry vivid memories of our visits to the temple. When you take your shoes off at the entrance, as you’re supposed to, you’re immediately struck by the contrast between the stone-cold floors and the dry desert heat outside. Then you’re deluged by the loud noises of the clanging of bells and chanting from the priest, and the powerful smell of incense, again in contrast to the relatively quiet and odorless streets outside. And when you approach the priest, you receive a laddu, a rich Indian sweet offering given to the gods, a ball of gram flour and ghee, flavored with cloves, raisins, nuts, and cardamom. It’s an explosion of intense flavor in your mouth.

That combination of sight, sound, smell, and taste generated something transcendent—it pulled me out of myself, even if only briefly. What made it even more striking was that it happened during a particularly difficult time in my childhood. When I was about seven or eight, my mom started to hallucinate and develop psychotic episodes. The experience of beauty in the temple seemed to be trying to convey something to me, like a point of light in an ocean of growing darkness. It seemed to suggest that there’s something more—something sweet and delightful in this world that I don’t create but is given to me.

As my mother’s illness progressed—she went undiagnosed and untreated for many years—we stopped going to the temple altogether, and I lost whatever little faith I had. A decade later, I became a Christian, but beauty wasn’t something I thought about except in conventional terms of physical aesthetics. It didn’t occur to me as a meaningful concept until I was studying for my doctorate in sociology.

In a course on social movements, I learned how protest movements are often fueled by moral outrage or negative emotional shocks. I began wondering whether those negative shocks were tied to hidden ideals of beauty. What makes the violation of some ideal worth fighting for? What is the violated good that someone is trying to restore? And what makes that good so desirable? Around that time, I stumbled upon Elaine Scarry’s book On Beauty and Being Just. In it, she argues that our encounters with beauty, such as symmetry in nature, spark a longing for justice: “it is the very symmetry of beauty which leads us to, or somehow assists us in discovering, the symmetry that eventually comes into place in the realm of justice.”

I wasn’t entirely convinced by her argument at the time, but it made me take beauty seriously. Later, as I studied the writings of faith-based activists like Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day, and Gandhi, I was struck by their frequent references to beauty alongside truth and justice, and the ways in which they saw these as inextricably linked.

These questions were percolating in my mind when I started a new project interviewing scientists around the world for a large study of scientists’ views of religion. When I asked them about the challenges they faced in their work, many described the sacrifices they had made: leaving lucrative careers in industry, enduring long hours, compromising their sleep and health, and even straining relationships with loved ones. When I asked why they did it, many responded with a word I didn’t expect: “Because it is beautiful.”

When we think of science, we often associate it with words like rational, analytical, and objective. Rarely do we think of it as beautiful. I didn’t anyway. Indeed, there’s a longstanding critique of science that it reduces or even strips away the beauty and mystery from reality. Think of the English Romantic poet John Keats, who complained about how “cold” scientific philosophy would "clip an Angel's wings / Conquer all mysteries by rule and line / Empty the haunted air ... Unweave a rainbow." But scientists in recent years have been speaking out against this caricature. Richard Dawkins, for example, in Unweaving the Rainbow, argues that, "The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable. It is a deep aesthetic passion to rank with the finest that music and poetry can deliver. It is truly one of the things that make life worth living."

I wanted to understand whether such beauty was really experienced by and relevant to scientists around the world. My team and I conducted the world’s first large-scale study of beauty in science: We surveyed nearly 3500 physicists and biologists in four countries and interviewed more than three hundred of them. The vast majority of them, we learned, share Dawkins’s insistence on the importance of beauty in their work. They describe it in different forms: sensory beauty, useful beauty, and the beauty of understanding.

Sensory beauty is perhaps the most immediate. The sensory beauty of the world—whether it is the interaction between a bee and a flower, or the vivid images produced by electron microscopes and the James Webb Space Telescope—is a powerful motivator for many scientists to pursue scientific careers in the first place. And in turn, their scientific knowledge heightens the beauty they experience in their lives. Physicist Richard Feynman was once accused by an artist friend of being incapable of appreciating the beauty of a flower, because scientists are reductionists. Feynman retorted that his scientific knowledge of the inner workings of a flower, rather, “adds to the excitement, the mystery, and the awe of a flower. It only adds.” For him, as for many scientists, the intricate beauty of nature is not diminished but enriched by science.

What we call useful beauty refers to the practical elegance of a theory or idea. Physicist Paul Dirac famously said, “It is more important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiment.” This is the beauty of simplicity and coherence—a beauty that unifies disparate phenomena into a single, elegant framework. It is the kind of beauty that guided Murray Gell-Mann in developing theories about fundamental particles and has inspired generations of researchers. Similarly, mathematician G. H. Hardy argued that mathematical beauty lies precisely in elegance and economy: “There is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.” For Hardy, as for many scientists and mathematicians, beauty is a reliable guide to truth. This is a disputed idea, however, since many theories that were once considered beautiful turned out to be false, and “ugly” theories, once demonstrated to be true, stopped being perceived as ugly. Beauty can be a misleading guide at times.

But the most profound form of beauty, many scientists told me, is the beauty of understanding. This is the beauty of discovery, of uncovering something new, of seeing connections that were previously invisible. It is the thrill of finding order where there seemed to be none, or of glimpsing the vastness of what remains unknown. One physicist in the UK described it to us as “looking into the face of God for nonreligious people.” It is this beauty of understanding that sustains scientists through long hours, failed experiments, and professional sacrifices.

These insights into beauty are not confined to science. Inspired by the stories I was hearing, I started a podcast and YouTube channel where I started interviewing people from diverse fields—scientists, architects, lawyers, athletes, and more—about the role of beauty in their work. Through these conversations, I realized that beauty is not limited to art or nature. It can be found in the purpose, process, products, and people involved in work across disciplines. For example, entrepreneur Luke Burgis explained how beauty satisfies deeper, enduring desires rather than mimetic ones borrowed from others. Psychologist Dacher Keltner highlighted the importance of moral beauty as a vital and pervasive source of inspiration. Immunologist Mark Painter contrasted the aesthetic appeal of scientific images and the deeper beauty of understanding intricate systems. Architect Rachael Grochowski spoke about designing spaces that foster calm, connection, and gratitude, blending beauty with spirituality. Musician and designer Chris Everett described beauty as “a shy peek at divinity,” a transformative force that fosters connection and healing.

My desire to share these conversations about beauty further led me to organize events—salon dinners, an interfaith retreat, and an international symposium—to create spaces for people to reflect on beauty. At the retreat, participants shared childhood memories of transcendent beauty, spent time in nature, and reflected on the obstacles to finding beauty in their work. One attendee noted, “Beauty is not always pretty, but it always requires connection.”

The salon dinners have been equally illuminating. I have organized these in cities around the world: Washington DC, Houston, New York City, Rome, Cambridge (UK), Toronto, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, and Dubai. These gatherings have brought together professionals from diverse fields to share stories of encounters with beauty in their lives and work. I was struck by how often beauty was described as a dynamic force—something that reveals, inspires, and connects. At one of our dinners, for instance, a BYU professor talked about the importance of the LDS hymn “There is beauty all around when there’s love at home,” and how he has found this to be true when creating an atmosphere of sincere love and mutual respect among students in his classroom.

So what has all this work taught me about beauty, and why does it matter? Across cultures and traditions, beauty has been linked to harmony, transcendence, and truth. Plato saw it as a bridge to higher realities. Aquinas understood beauty as reflecting the harmony, order, and radiance of God's creation, drawing us toward the divine through its clarity and fittingness. Kant viewed beauty as arising from the free play between imagination and understanding, creating a universal sense of harmony and delight. Today, however, beauty is often dismissed as superficial or even oppressive—not without reason, given how beauty standards have been weaponized to enforce exclusionary ideals of race, gender, and class. But such dismissal assumes too reductive a conception of beauty.

Theologians like von Balthasar teach us that what is objectively beautiful transforms the beholder, drawing her into a kind of union with itself. He insists that “whoever sneers at [Beauty’s] name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past—whether he admits it or not—can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.” As philosophers like Michael Spicher argue, beauty is a basic reason for action. We can’t do without it.

In a world fractured by division and distraction, recovering the concept of beauty could help us reconnect—to ourselves, to each other, and to God. But we need to learn to attend to it. As Roger Scruton argues:

“Beauty can be consoling, disturbing, sacred, profane; it can be exhilarating, appealing, inspiring, chilling. It can affect us in an unlimited variety of ways. Yet it is never viewed with indifference: beauty demands to be noticed; it speaks to us directly like the voice of an intimate friend. If there are people who are indifferent to beauty, then it is surely because they do not perceive it.”

Attending to beauty can generate in us a commitment to caring for the world. As Elaine Scarry insists, that which we perceive as beautiful incites in us “an urge to protect it, or act on its behalf.” Hannah Arendt makes this point powerfully:

““[B]eauty is the very manifestation of imperishability. The fleeting greatness of word and deed can endure in the world to the extent that beauty is bestowed upon it. Without the beauty, that is, the radiant glory in which potential immortality is made manifest in the human world, all human life would be futile and no greatness could endure.”

Perhaps this is the promise beauty offers: not just to make life bearable, but to make it worth living—and worth living because we are not alone. Beauty is a sign, an invitation, beckoning us beyond itself to something greater, towards a presence that ultimately meets the heart’s deepest longings. And today, as I look back on my life, I see this promise echoing softly through the myriad encounters with beauty—even in the Hindu temple in Oman, in something as unassuming as the taste of a laddu. I recognize it now as the voice of God, whispering through beauty: I am here.

Dr. Brandon Vaidyanathan is Professor of Sociology and Director of the Institutional Flourishing Lab at The Catholic University of America.

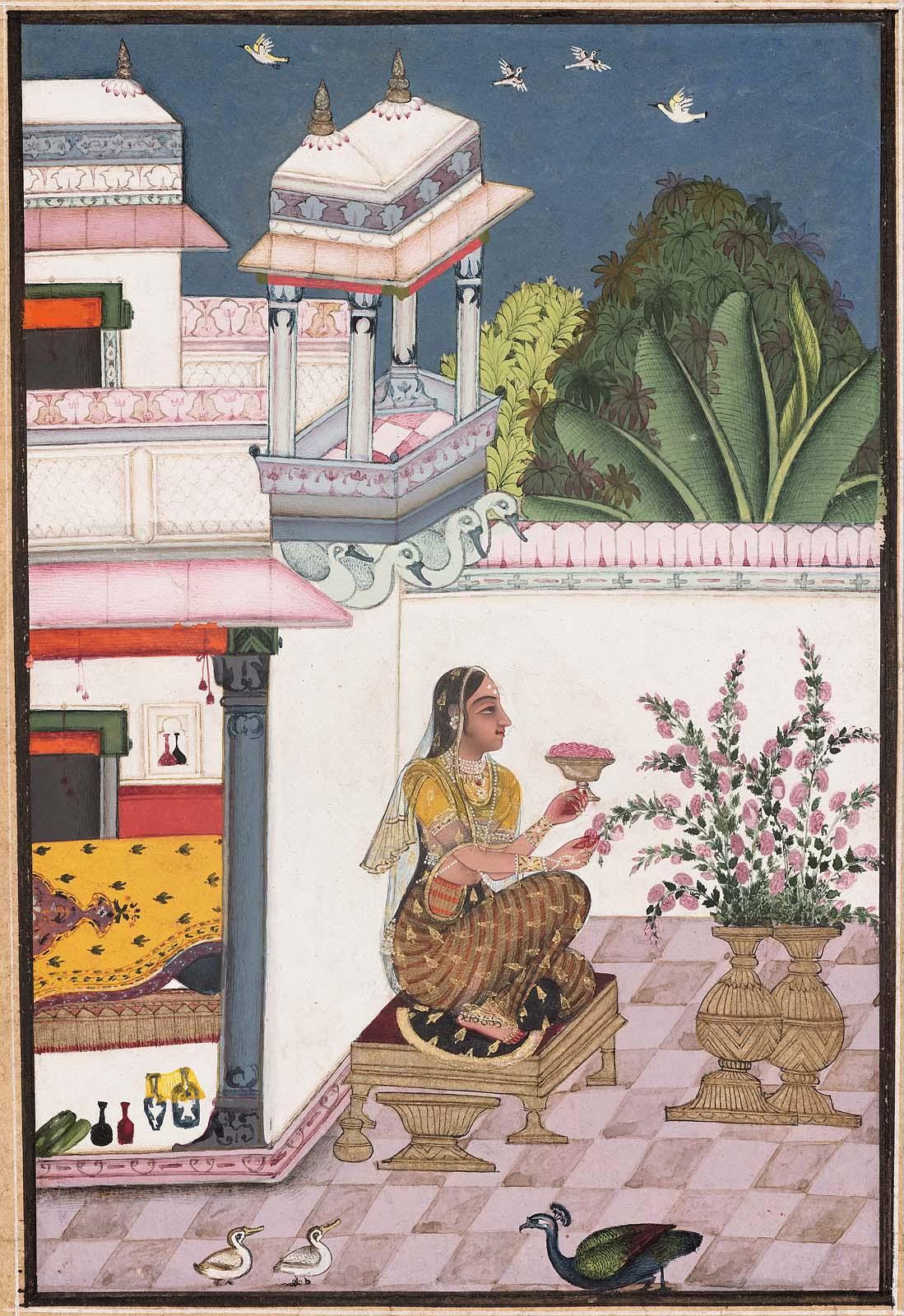

Art from the Boston Museum of Fine Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and British Library.

I have felt this longing ache of divine beauty in many places: cathedrals, redwood forests, high mountains, art museums, sunsets, classical music and temples. I love that truth and beauty - God - can be found in so many places and circumstances