Please find here our collection of art and writing to inspire you this Easter season. If you would like to receive these Holy Week meditations in your inbox, please subscribe to Wayfare and then manage your subscription under your account and turn on notifications for Holy Days.

“There came a woman having an alabaster box of ointment of spikenard very precious; and she brake the box, and poured it on his head. And there were some that had indignation within themselves… and they murmured against her. And Jesus said, Let her alone; why trouble ye her? she hath wrought a good work on me… She hath done what she could: she is come aforehand to anoint my body to the burying. Verily I say unto you, Wheresoever this gospel shall be preached throughout the whole world, this also that she hath done shall be spoken of for a memorial of her.” —Mark 14:3-9

MEDITATION

“Spy Wednesday,” (a reference to the conspiracy of Judas to betray Christ,) offers us the opportunity to consider the contrast between the unnamed, outsider woman who understood and supported who Jesus was and what he came to do, and the named apostle who failed to do so.

Who are the women of faith you remember today? Who goes unnamed by history but deserves our recognition? Who are the outsiders who can help us better see who Christ is?

ACTIVITY

Share with each other the stories of the women in your life who have testified to you of Christ.

ESSAY

CLOTHING OURSELVES IN CHRIST Deidre Nicole Green

Full disclosure: I love wearing garments. I know this is not everybody’s stance, but it is mine. After receiving my endowment over twenty years ago, I had the experience a lot of people have—I was somewhat stunned and unsure what to make of it. Since we were given less information about what to expect back then, I remember being surprised and puzzled, and although I could feel that something was fundamentally different about me afterwards (I’ve been teased for publicly characterizing this change as an “ontological shift”), I couldn’t quite make sense of the temple ceremony and was not eager to repeat the experience (though my evolving love for temple worship belongs in a separate essay entirely).

Yet even in the stunned and sober state in which I remained for a few days following, I was thrilled to wear garments. I remember standing over the washing machine in my parents’ home and (rather obsessively and perfectionistically) asking my beloved maternal grandmother for guidance on how to wash them correctly because I didn’t want to risk any damage to them or disrespect them. I felt an innate reverence for them. In a way I could not begin to explain at twenty-one, I felt at home in the garment; I felt as if I had come home, as if I had come home to myself or become myself in a new way now that I inhabited this sacred, religious clothing. Through both personal experience and scholarly reflection, I have come to believe that the garment is formative of our subjectivity, that wearing the garment symbolizes our willingness to let Christ shape our very selfhood. In what follows, I explore a theology of the garment that can help us make meaning of its role in our lives of discipleship in the twenty-first century.

Recently, Church leaders have initiated and engaged in more discussion about the garment in general conference and other venues. Latter-day Saints have been reminded that “we find Jesus . . . in the symbolism of the garment.” Young Women General President Emily Belle Freeman explains in her October 2023 general conference talk that she wears “the holy garment as a constant reminder” of her covenants and her choice to walk the covenant path with Jesus Christ, “because I want to live in committed covenant relationship with Him.” President Russell M. Nelson declares, “when you put on your garment, you may feel that you are truly putting upon yourself the very sacred symbol of the Lord Jesus Christ—His life, His ministry, and His mission, which was to atone for every [child] of God.” Perhaps even more pointedly, in a recent BYU devotional, Elder Allen D. Haynie teaches that the most important of the multiple symbolic meanings of the garment is “a remembrance of the Savior’s sacrifice in the Garden of Gethsemane and on the cross and His glorious Resurrection.” J. Anette Dennis, First Counselor in the General Relief Society Presidency, further explains both how garments tie to the Atonement of Jesus Christ and how through them he becomes interwoven with our very identities:

The garment of the holy priesthood is deeply symbolic and also points to the Savior. When Adam and Eve partook of the fruit and had to leave the Garden of Eden, they were given coats of skins as a covering for them. It is likely that an animal was sacrificed to make those coats of skins—symbolic of the Savior’s own sacrifice for us. Kaphar is the basic Hebrew word for atonement, and one of its meanings is “to cover.” Our temple garment reminds us that the Savior and the blessings of His Atonement cover us throughout our lives. As we put on the garment of the holy priesthood each day, that beautiful symbol becomes a part of us.

Through wearing the garment, and doing so whenever possible, Jesus Christ and his Atonement exert constant influence on us and shape our subjectivity, becoming a part of who we are.

In my essay entitled “Enveloping Grace,” I discuss Christ and his Atonement as enveloping and containing us as individuals. Drawing on the thought of feminist theologian Serene Jones and others, I argue that sin, as well as social and cultural forces, can leave a person diffuse, dissolute, and fragmented rather than held together in a coherent whole as a subject. Jones and other feminists highlight that this dissolution of the self may be a problem particularly for women, who are socialized to give so much of themselves to others and to identify so much with the needs, desires, and objectives of others that they lose themselves.

Gender is, of course, not the only lens by which to identify the disparate ways in which sin can distort selfhood; process theologian Catherine Keller argues that sin may result in the “soluble self” that I have been describing, which stands in contrast to a “separative self,” defined by pride and domination over others. Everyone, regardless of gender, can experience one pattern or the other or oscillate between the two. In any case, Jones theorizes divine grace as that which envelops and thereby contains the multiple and fluid self, thereby preventing them from being “dissolved into the projects, plans, and desires of others,” which would leave them “without a ‘skin’ to define the integrity of [their] personhood.” Insofar as divine grace intends a person’s ultimate flourishing, it provides her with a “skin of her own (and God’s) best desires” so that she is “clothed in grace.”

Jones’s theological reflections are influenced by feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray, who articulates women’s need for a divinely gifted “envelope” to contain them as a cohesive self so they can find and situate themselves in their own place. According to Irigaray, the first envelope given to a person is the body, which serves as the boundary delineating the individual from other bodies. Irrespective of gender, allowing anyone to be both separate and whole, this corporeal demarcation is especially crucial for women, who tend to become dissolute in response to cultural expectations. This envelope provides self-definition and appropriate boundaries, offering a woman integrity and individual wholeness. Additionally, such a providential envelope protects a woman from adopting inauthentic forms of envelopment that she might seek in the world in an effort to construct a false or superficial sense of self-identity, including “clothes, make-up and jewellery.” These artificial envelopes prevent her from receiving more authentic forms of envelopment and therefore from establishing more genuine forms of selfhood.

Irigaray’s analysis suggests that cultural forces that demean women and erode their corporeal boundaries leave them amorphous and vulnerable so that they need an enhanced mode of envelopment. For Jones, this divinely gifted envelope is Christian grace. Adding to the argument made by these feminist thinkers (which centers around women but is just as productively conceived in terms of the soluble self)―that the containment or envelopment that grace provides functions to hold together the soluble self as an individual with integrity, rather than dissolving into a diffuse and amorphous self―I would say that grace also can function to contain the separative self from overreaching bounds and doing harm to others. In this way, the garment symbolizes the way in which Christ can serve as a mediator in all human relationships. He and his grace stand between me and all others, informing and forming those relationships and intersubjectivities.

Moreover, in response to the temptation to adopt an artificial envelope in a world that constantly lies to me about the source of my selfhood and value as a person, my garment reminds me that, as a consecrated being, I have an extra layer of protection from the various social and cultural forces that want to reduce my body—an inextricable part of my soul (D&C 88:15)—to an object of consumption or commodification; it endows me with an added power to resist these forces of commodification, serving as a physical buffer and barrier that reminds me that my body belongs to me and its Creator. At the same time, the garment marks me as belonging to a consecrated community, which further highlights the intersubjective nature of becoming a self and a Christian disciple.

The notion of grace as envelopment by the divine resonates with Restoration scripture, which offers multiple depictions of Christ’s Atonement and redemption as encircling and enveloping us. For example, Lehi, in testifying that the Lord has redeemed his soul, declares: “I have beheld his glory, and I am encircled about eternally in the arms of his love” (2 Ne. 1:15). For me, there can be no better symbol of the way in which divine grace, made possible through the Atonement of Jesus Christ, contains me as a cohesive self than the garment, which literally offers a second skin to resist the pressure to create a false identity or form a pseudoskin that is merely a product of the fallen world in which I live. The garment restrains the forces that would undo my selfhood. The garment is a tangible reminder that I am constituted as a subject by Christ’s grace and only by that grace; the grace made possible by the Atonement of Jesus Christ and in relationship to him is the only reason I enjoy selfhood.

That the garment forms my subjectivity helps to explain why wearing it consistently and whenever possible is emphasized by Church leaders. I might think of it as being nearly—or actually—essential to my self. Postcolonial feminist theorist Meyda Yeğenoğlu, writing on the veil worn by Muslim women, observes that religious clothing is “a dress which we might consider as articulating the very identity” of a religious person. According to her, this “sartorial matter” is not external to one’s identity but rather exists “as a fundamental piece conjoined with the embodied subjectivity” of a person and as part of the body itself, such that she is “constituted in (and by) the fabric-ation of” it. For Yeğenoğlu, the impulse to “unveil” the Muslim woman in a liberatory effort can only amount to an imperialist tendency that might threaten the very subjectivity of a religious person whose identity is interwoven with her religious attire. She maintains that conceptualizations of the body, along with bodily presentation and performance, are culturally constructed and therefore culturally specific.

Moreover, in keeping with the concern articulated above about artificial forms of envelopment and the commodification of the body by Western capitalism and culture, Yeğenoğlu employs postcolonial critique to reject the application of Western standards to non-Western contexts, opining that Muslim women’s religious clothing does not confine or discipline the body to a greater degree than does Western culture: “Emphasizing the culturally specific nature of embodiment reveals . . . that the power exercised upon bodies by veiling is no more cruel or barbaric than the control, supervision, training, and constraining of bodies by other practices, such as bras, stiletto heels, corsets, cosmetics, and so on.” This final point helps us to rethink the garment as something that resists the commodification of the body rather than merely something to cover, control, or constrict the body. It suggests that to see the garment as restrictive is to see one cultural standard, namely that of Western capitalism, as natural rather than as a cultural construct that does harm to the soul and that to subscribe to that standard is somehow more conducive to freedom than religious dress.

I suggest that the garment is neither a vestige of a magical worldview nor an arbiter of Victorian ideals of modesty; rather, its purpose is to be formative of a person’s subjectivity. It forms Latter-day Saints as consecrated individuals and forms us as followers of and in likeness to Christ, who epitomized consecration. The garment is symbolic of the veil of the temple, which is not only symbolic of Christ but is also the place in which we present ourselves before the divine. In an embodied way, we pronounce our total presence, availability, and openness to divine call, the tangible equivalent of verbal exclamations of women and men in the scriptures who played pivotal roles in salvation history by declaring, “Here I am!”(see Gen. 22:1; see also Gen. 22:11, 31:11, 46:2 and Luke 1:38). Such a pronouncement is to me the essence of consecration, and I believe that the garment represents my perpetual position before the veil, reminding me that I am forever at the disposal of the divine.

Moreover, the veil is a place where our utter dependence on God is epitomized: no matter how much I know or think that I know, in this space I always perform epistemic humility, demonstrating my total reliance on God for salvific knowledge, salvation, and exaltation. Ultimately, we come to be subjects only to the degree that we recognize our total dependence on God, and so this reminder is crucial to the process of formation as a subject. The Book of Mormon teaches that the humility that acknowledges this total dependence combined with faith affords “communion with the Holy Spirit” (Jarom 1:4), which is to say that it affords union, mutual relationship, and communication with the Holy Spirit.

The garment provides a constant tangible reminder of that dependence and of the intimate relation with deity that is always available to us as we acknowledge that dependence. Wearing the garment demonstrates that we “have clothed [ourselves] with Christ” (Gal. 3:27, NRSV), put on Christ (Rom. 13:14, KJV), and thereby “clothe [ourselves] with the new self, created according to the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness” (Eph. 4:24, NRSV). In order for the garment to exert its full efficacy in our lives, we must theologize and conceptualize it properly. I believe that as we conceive of the garment as sartorial grace, which we are in constant need of, we can come to be embodied and formed as subjects by Christ and his Atonement.

Deidre Nicole Green is an Assistant Professor of Latter-day Saint/Mormon Studies at Graduate Theological Union and publishes on constructive feminist theology, Kierkegaard, and Mormon Studies.

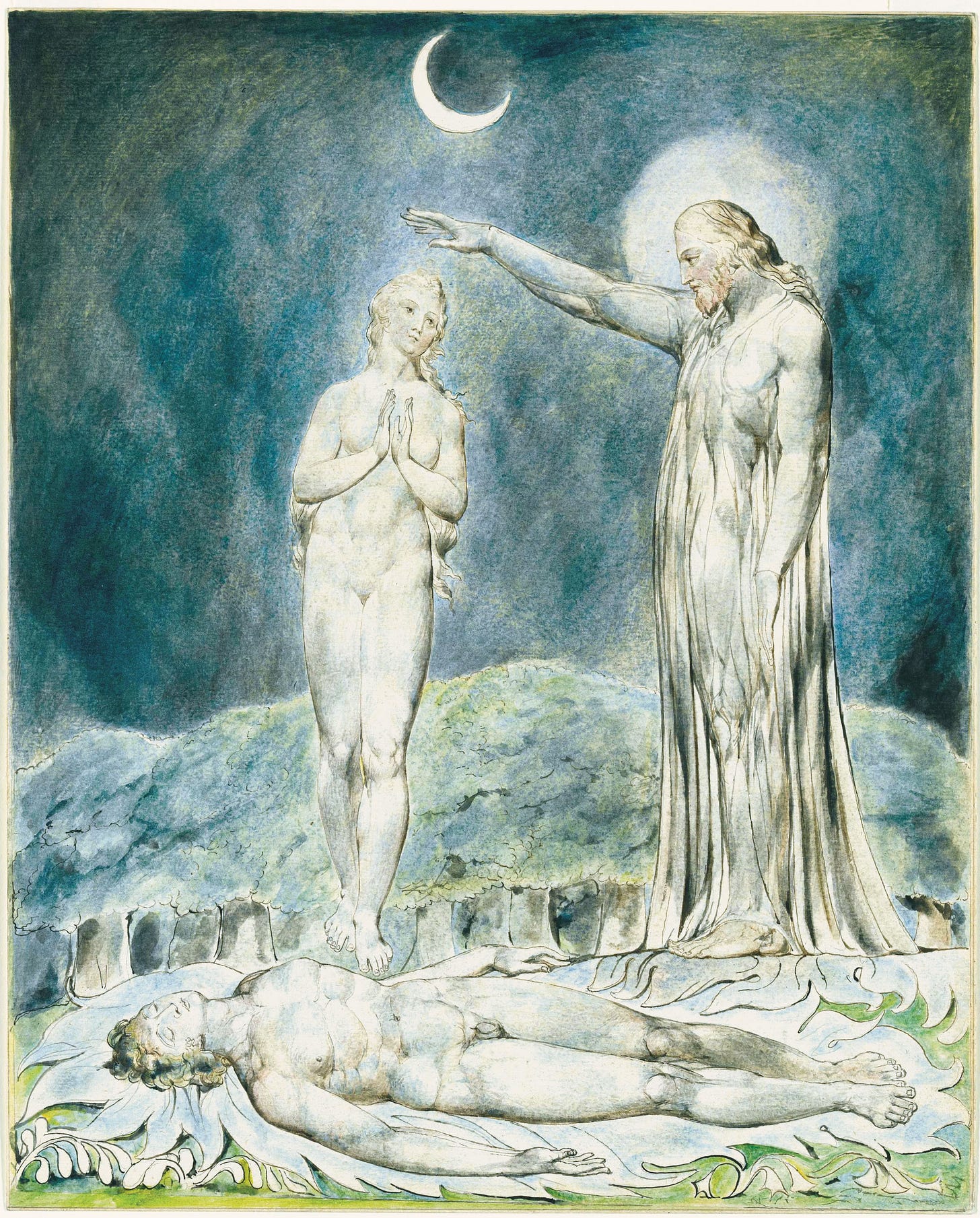

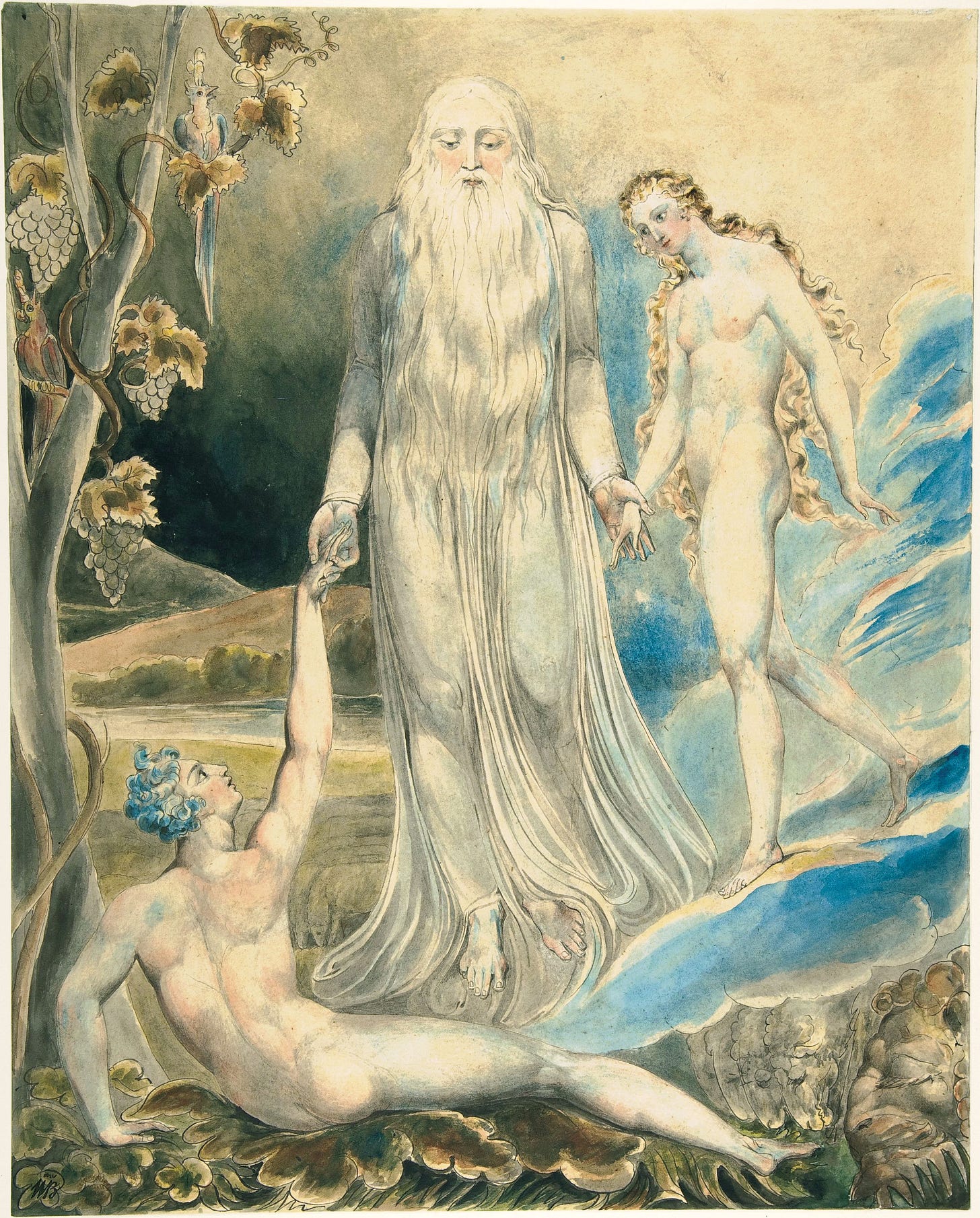

Art by William Blake.

I really loved your reflection on the gift and sacred blessing of wearing the garment. I teach temple prep and I am always trying to help those preparing for the temple to see the garment as a choice and a gift rather than an inconvenience or task.