She Loved Much

The Gospel of Luke tells the story of a woman who unexpectedly entered a banquet, approached Jesus in tears, and washed his feet with nothing more than her hair. The other Gospels mention Mary, Lazarus’s sister from Bethany, anointing Jesus with spikenard shortly before Jesus’s death. These episodes share similarities, leading to modern interpretations that blend them together. Luke’s account, however, does not describe the anointing at Bethany, and the unnamed woman in this story was not Mary. By examining the tale of the “city woman” on its own and considering its historical setting, we gain valuable insights into her behavior and how Jesus responded to the men who judged her.

Narrative Sequence and Galilean Setting

We have strong reasons to believe the synoptic Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke began as stories and sayings shared among Jesus’s earliest followers before they took written form.1 If we analyze the texts with this in mind and look for likely patterns of transmission, we end up with individual story units, or pericopes. These pericopes sometimes appear in all three Gospels, sometimes two, and sometimes within a single Gospel tradition. Although scholars debate how to divide and arrange these pericopes, general strokes emerge from their collective narration of Jesus’s life and ministry. We notice Jesus beginning his ministry in Galilee, departing for provincial areas of Judaea, and ending in Jerusalem during Passover where he was executed on the cross.

To drill down further, we would have to consider the technicalities of the different Gospel traditions and the particular details of each pericope. An intelligible alignment and sequence weighs the many historical and textual variables—put simply, the Gospels as a collective narrative place Jesus in Nazareth at the outset of his Galilean ministry, indicate movement toward Capernaum and other villages along the northern shoreline of Lake Gennesaret, and describe Jesus eventually venturing into communities in the opposite direction. After sending the Twelve on their first preaching tour, the pericopes mention Jesus visiting Galilean “cities,” or rather Galilean polesin as the earliest Greek texts have it. This term, like the suffix -polis in many city names today, had to do with a more elaborate polity than smaller villages, but we shouldn’t assume an urban quality or larger population of the “cities” in these stories. These were towns by today’s terminology.

Jesus’s ministry appears to have evolved from a primarily Jewish, tightly networked villager community into a more pastoral, mixed audience setting. Jesus began to speak with people from different backgrounds and everyday routines than those of the fishing economy of Capernaum and Bethsaida. He used comparatively more storytelling, less legal juxtaposition between Torah and his own teaching, more commonfolk imagery, and less prophetic vocabulary.

He also confronted the space of encounters between Jewish people dedicated to observing ritual purity at all times—the Perishayya or “set apart ones,” who appear in our English Bibles as “Pharisees”—and individuals seen by their circumstances or status as ritualistically unclean. All four Gospels present pericopes of Jesus being anointed by a woman, but the one in Luke departs from the others to describe a “city woman” known to local Pharisees as a “sinner” washing Jesus’s feet with her tears and hair. In context and in the Gospel pericope sequence, here was Jesus not only faced with the ramifications of his parables and proverbs at an early stage of his ministry, but also seated literally and figuratively in the contested middle ground between the clean and the unclean, the “sinner” and the “set apart.” How he responded to both manifested a crucial application of his teaching just before that occasion that he invites all the weary to find rest in him, where his yoke won’t weigh them down and where he will lift their burdens.

Anointed by Hair, Tears, and Unguent

Luke presents the story of a “city woman” washing Jesus’s feet during a dinner with Pharisees while Jesus ministered throughout Galilee (Luke 7:36–50). This episode is often mixed with the anointing at Bethany during the last week of Jesus’s life when Mary brought spikenard ointment and applied it to Jesus’s head (Mark 14:3–9; Matthew 26:6–13; John 12:1–8). Because of a couple of shared elements between these two episodes, readers have conflated them, even going so far as to associate Mary with washing Jesus’s feet and the Pharisees calling Mary a sinner. The conflation has done a terrible service to Mary Magdalene by further stretching the insinuations of “sinner,” creating an old folkloric tradition that she turned from a career of prostitution to follow Jesus (something not remotely defensible in the Gospels). Moreover, the Gospels leave ample room (some scholars argue the case is settled) for Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene to represent different women, which would further distinguish Mary Magdalene’s relationship to Jesus from the “city woman” in Luke’s story.

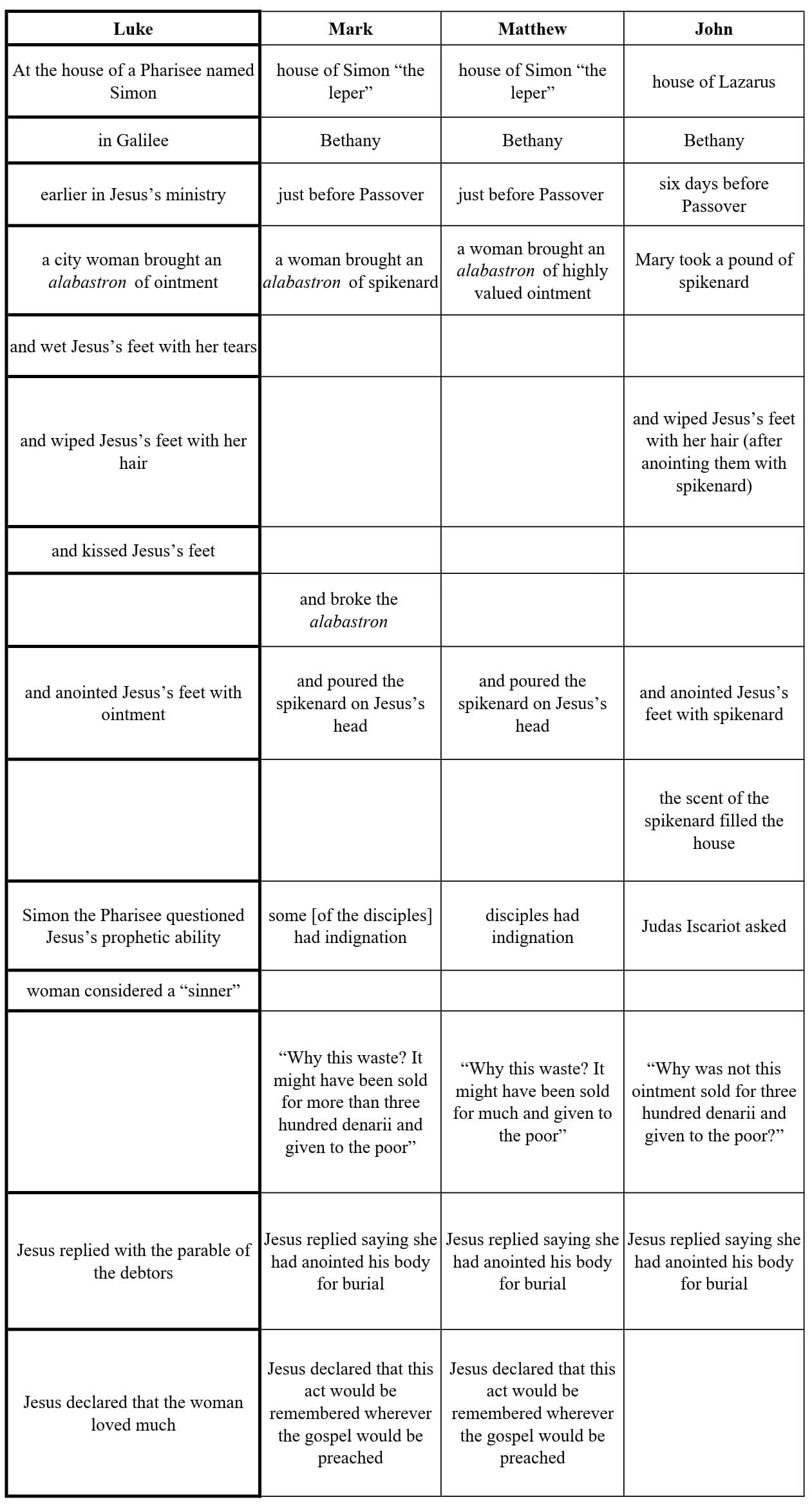

Important differences between Luke’s story and the anointing at Bethany depicted in Mark, Matthew, and John include:

When the story elements are compared, we see greater harmony between Mark, Matthew, and John than with Luke. The context for Luke’s story also departs from the others in significant ways. Luke has a Pharisee named Simon among the provincial audience who invited Jesus to dinner. We know others also attended because of a reference to “they that sat at meat with him” (Luke 7:49), but the story revolves around Simon, Jesus, and the unnamed woman who entered the banquet from behind Jesus. From other historical sources, we can surmise how this appeared. The group likely surrounded a low central table with individual cushions in a common area of a Galilean domicile. Once the host brought food to the table, the group took their seats and reclined sideways to the edge of the table, using their table hand to eat. As the guest, Jesus probably sat at the corner of the table, meaning his back would have faced the outer rooms of the domicile while he spoke to others surrounding the table.

A woman from another town (or polis) nearby heard how Jesus had dined at Simon’s house, and she arrived after the company had already sat to eat. She carried an alabastron of unguent (more on this in a moment) and approached the dining area from behind Jesus—moving straight toward the honored guest without giving deference to the host, a breach of etiquette. She lowered herself to Jesus’s feet, and weeping, wet his feet with her tears. She took her hair and wiped the dirt from his feet, then kissed them, took the phial, and rubbed unguent onto his feet.

Hospitality Culture

In Jesus’s time, hospitality culture of the Judaean variety often included hosts providing guests with a cushion or couch to sit on, bringing a basin of water and a towel, and washing their guests’ feet. Unguent, an essential oil similar to menthol, worked as a kind of analgesic, a soothing balm for feet. Respectable hosts used marble, fine-metal, or Egyptian calcite phials as ointment containers for esteemed guests; we don’t know what material this woman’s alabastron was made of, and given her status and location, probability leans toward hers being of a locally sourced material, like terra-cotta or common stone. Archaeologists have identified phials and jars referred to as “alabaster” but made of such diverse materials as gypsum, serpentine, faience, glass, limestone, obsidian, agate, breccia, carnelian, hematite, jasper, and even organic materials such as wood, bone, and ivory.2 Alabastra were often decorated with the images of goddesses or floral ornaments, and hers could potentially have incited Simon’s suspicion for its resemblance of idolatry, though all Luke’s account suggests is an overall lesser esteem for the woman and not her alabastron.3

The woman who approached Jesus came with no basin, no water to wash Jesus’s feet, no towel, and the unguent she brought was visibly not of the spikenard variety that was used for the most elite occasions, even coronations. Her phial was of the cheap kind, not sealed and broken open only once, but carried in everyday material. Taken in context, the Lukan story presents an impoverished woman lacking in fashion and decorum, entering the room not as the host’s servant or member of the host’s household but as an outsider. The men in the room, Pharisees all, looked on, embarrassed. She seemed undignified and among the unclean class who did not properly attend to daily purification, hence, a “sinner.” As Simon looked on, he thought Jesus could not possibly be a prophet; otherwise he would have known how an impure woman was touching him, an act rendering Jesus unclean according to Jewish law and requiring miqveh purification.

Jesus confronted the hospitality expectations head-on. He asked Simon to see this woman—“I entered into thine house, thou gavest me no water for my feet: but she hath washed my feet with tears, and wiped them with the hairs of her head. Thou gavest me no kiss: but this woman since the time I came in hath not ceased to kiss my feet. My head with oil thou didst not anoint: but this woman hath anointed my feet with ointment” (Luke 7:44–46). When these men took notice of the woman’s poor attempt at hospitality, Jesus stood up for her and pointed out their relative inhospitality.

“Sins, Which Are Many”

The King James Version has Jesus telling her that her “sins, which are many, are forgiven” (Luke 7:47). The word “sins” in this pericope is the same term used in the Greek Old Testament, the Greek New Testament, and other ancient Greek texts to describe errors, mistakes, and missing the mark. It dealt particularly with social codes that established etiquette and proper civic conduct. One could say this woman, by her lack of proper hospitality elements, made certain faults of courtesy, like someone barging into the old English royal court, calling the King and Queen “buddies,” dressing all wrong, and walking across the room without bowing and curtsying. Pharisaic and regional custom treated such bad etiquette as shameful, even threatening the purity of those present. Torah said touching or being touched by the unclean rendered one defiled and in need of purification. By implication, the woman made Jesus unclean by her crude behavior, which could easily have brought a sneer, chuckle, or gasp from the men in the room.

Given the historical context and ancient use of the Greek term rendered as “sins” in the King James Version, one could read Jesus as saying, “her many shortcomings are acceptable.” Jesus even invoked a short story to illustrate this sense of the term, describing two debtors, one who owed ten times as much as the other, and the creditor letting their debts go out of pity. In context, this suits the situation: We can all detect the gaffes in her gestures, but someone who more frequently bungles social customs appreciates our grace more than a fashionable person with nearly perfect manners.

Jesus’s reaction here is monumentally instructive. He reorients everything by his response to this woman. For him, none of the outer hospitalities looked at all out of place—for she loved much, he said. He saw what no one else apparently had been willing or able to see, that she approached Jesus with love. He stood up for her in the company of the most technically astute readers of Torah and of tradition, the Pharisees. He received her authenticity without hesitation, and to the shock and dismay of his hosts, he elevated her in their presence and sent her with his blessing.

This woman who loved much broke all the protocols while trying to observe them. Her version of honoring Jesus with her hospitality looked to others like a pitiful encounter. But she brought all she had. She cleaned Jesus’s well-worn feet with her own tears, she took her own hair to wipe the dirt, and massaged her rudimentary balm into his footsoles. Jesus showed his unfailingly good soul by his response. If we were to hear that Jesus were near, and if we were to try to approach him, even getting things all wrong, if all we had were our tears and our hair, Jesus would receive us and stand up for us and bless us. Like this humble, lovely woman, do we love much? Or, like the Pharisees in the room, do we concentrate on whether people do things according to protocol?

The story further demonstrates what Jesus had promised by his invitation to take upon ourselves his yoke. A woman in tears approached him, and he lifted her, literally from the floor, and offered her peace and comfort. You can’t shame Jesus—not with social customs, not with scripture, not with tradition, not with etiquette or fashion or your incredulity or spite. She loved much, and so does he.

RELATED SOURCES

B. Hudson McLean, The Cursed Christ: Mediterranean Expulsion Rituals and Pauline Soteriology (Sheffield Academic, 1996).

Stephen Finlan, “Atonement,” Oxford Bibliographies (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Jean-Louis Flandrin, Massimo Montanari, and Albert Sonnenfeld, eds., Food: A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present (Columbia University Press, 1999).

Catherine Hezser, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine (Oxford University Press, 2010).

James W. Ermatinger, Daily Life in the New Testament (Greenwood Press, 2008).

David Golding is a historian in the Church History Department and the general editor of the Restoration Scripture Critical Editions Project.

Art by El Greco, The Feast in the House of Simon, c. 1608–14, The Art Institute of Chicago.

EVENT

BAY AREA COUNCIL FOR

LATTER-DAY SAINT STUDIES

February 1, 7:00 PM

David Golding

Exploring the Evolution of Scripture

We are excited to announce an evening with David Golding from the Church History Library. Golding will be speaking at the Oakland Temple Visitor’s Center on February 1 at 7:00 PM. Dive into the fascinating history of Latter-day Saint scripture with this review and update of the Restoration Scripture Critical Editions Project. Unlike popular editions that present a single, static reading, a critical edition unpacks the changes across manuscripts and printed editions, revealing the dynamic evolution of sacred literature. This presentation demonstrates how textual and source criticism extend beyond technical and academic work to offer practical benefits that deepen everyday reading and interpretation. It also looks behind the scenes at how custom automation tools accelerate this massive task, rapidly collating sources and tracking each and every variant.

Golding is a historian with the Church History Library. He has a Ph.D. in the history of Christianity from Claremont Graduate University and has taught at Brigham Young University. He has published widely in Latter-day Saint Studies and is a co-editor of “Missionary Interests: Protestant and Mormon Missions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.”

Who: David Golding

What: Exploring the Evolution of Scripture

When: Sunday, February 1, 2026, 7:00 pm

Where: Oakland Temple Visitors’ Center, 4766 Lincoln Ave, Oakland

Live stream: https://zoom.us/j/91767304658

Past Event Recordings

Recordings of past events are available on the Event Archive page of the Latter-day Saint Council website.

BAY AREA COUNCIL FOR LATTER-DAY SAINT STUDIES

ldscouncil.org

For a layperson’s overview of the source problem of the Four Gospels, see Rafael Rodríguez, Oral Tradition and the New Testament: A Guide for the Perplexed (Bloomsbury; T&T Clark, 2014). For deeper analysis, see Alan Kirk, Jesus Tradition, Early Christian Memory, and Gospel Writing: The Long Search for the Authentic Source (William B. Eerdmans, 2023); Eric Eve, Behind the Gospels: Understanding the Oral Tradition (Fortress Press, 2014).

Recent archaeology has found alabastra of such diverse materials and locations of manufacture that a reference to alabastron in any ancient Mediterranean text would almost certainly describe the container and not the material of alabaster. Earlier assumptions that the Greek word alabastron referred only to luxurious vessels for ointments made in Egypt out of calcite were based on a narrow range of Egyptian alabastra from dynastic ages. Luxury alabastra sourced in Egypt and exchanged across the Mediterranean into the late Hellenistic period were not identical to common alabastra sourced from local manufacture of many different materials, such as limestone, gypsum, travertine, aragonite, terracotta, and various carbonite rocks. The two calcite-alabaster bathtubs belonging to Herod the Great, assumed to have been Egyptian imports, were discovered to have been locally quarried in Judaea, from specifically the Te’omim cave—so even the most luxurious manufacture for a contemporary of Jesus in the same trade corridor as Jesus’s audiences was not necessarily made of Egyptian alabaster. See Ayala Amir, Amos Frumkin, Boaz Zissu, Aren M. Maeir, Gil Goobes, and Amnon Albeck, “Sourcing Herod the Great’s Calcite-Alabaster Bathtubs by a Multi-Analytic Approach,” Scientific Reports 12, no. 7524 (May 7, 2022): 1–10; Dorothy Kent Hill, “An Early Greek Faience Alabastron,” American Journal of Archaeology 80, no. 4 (Autumn 1976): 420–423; Sandra Knudsen Morgan, “An Alabaster Scent Bottle in the J. Paul Getty Museum,” The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 6/7 (1978/1979): 199–202; Rachel Thyrza Sparks, Stone Vessels in the Levant (Routledge, 2017); Jorrit M. Kelder, Laurent Bricault, and Rolf M. Schneider, “A Stone Alabastron in the J. Paul Getty Museum and Its Mediterranean Context,” Getty Research Journal 10 (2018): 1–16; Giuseppe Scardozzi, “The Provenance of Marbles and Alabasters Used in the Monuments of Hierapolis in Phrygia (Turkey): New Information from a Systematic Review and Integration of Archaeological and Archaeometric Data,” Heritage 2, no. 1 (February 2019): 519–552.

I owe Ryan Saltzgiver for this fascinating interpretive possibility.