Rendering the Logos

On David Bentley Hart’s "All Things Are Full of Gods"

A few years ago, the theater director David Cromer staged a wonderfully imaginative version of the Thornton Wilder play, “Our Town,” on Broadway. Cromer himself played the part of the Stage Manager, the folksy everyman with the New Hampshire accent, who introduces the audience to the people of Grover’s Corner and sometimes interacts with the characters themselves. But instead of avuncular charm, Cromer played the part with the joyless efficiency of an overworked barista calling out orders at the corner coffee shop. Everything was stripped of all affect. No accents. No colorful period costumes. Not even stage lighting. The house lights were left on for the duration. That’s at least how things stood until the third act when the Stage Manager informs the audience that Emily Gibbs, the lively girl whose story they have followed from the very beginning—from her innocent childhood, bathed in the smell of heliotrope, to her courtship and marriage to the neighbor boy George—has died in childbirth and that the burial in the town cemetery they are witnessing is hers.

A quick cut to the afterlife, populated by a strange assemblage of lifeless, ghostly characters, and one learns that the newly deceased Emily has been given the opportunity to relive one day one last time, the day of her 12th birthday. It is at that moment in Cromer’s production when a bit of theatrical enchantment occurred. The house lights finally fade to dark; the stage lighting comes on; and one is confronted with the Gibbs house on the day of that childhood revelry. This time, however, it is bathed in the sights, sounds, and even smells of an idyllic family home in turn-of-the-century America. There are finely tailored costumes, a riot of color, a Victorian kitchen where Mrs. Gibbs is cooking an actual breakfast, and the smells of bacon wafting through the theater. It is a feast for the senses, all of which renders Wilder’s point all the more poignant: “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?—every, every minute?” Emily asks. “No,” replies the Stage Manager, a bit wistfully. And then after a pause, he adds, “The saints and poets, maybe—they do some.”

I couldn’t help but think of this scene while reading David Bentley Hart’s recent book, All Things Are Full of Gods, his extraordinary reflection on the philosophy of mind and the nature of consciousness. Hart is considered one of the finest living religious philosophers, and what he does in this book is similar to what Cromer did in his staging of “Our Town”: to charge the familiar—in this case life, language, thought itself—with the shock of the new. The book is almost too lovely to talk about in terms of problems and solutions, but doing so might help set the stage.

The problem in question is how “mind” fits in a world that modern science assumes to consist of little more than purposeless matter and forces, what Hart and others call the “mechanistic philosophy.” Mind seems like a different thing entirely, for a number of reasons, but let’s just consider three. There is, first of all, a subjective aspect to experience that cannot be reduced to third-person scientific description, what philosophers call “qualia.” For example, I can describe what it’s like listening to Glenn Gould’s rendition of Bach’s “Goldberg Variations,” yet, no matter how precise my description—drawing careful attention to the tonality, dynamics, tempo—I still cannot capture the first-person experience of listening to Gould’s recording. The mechanistic philosophy, rooted in third-person perspective, seems to be missing something.

There’s also “intentionality,” a term philosophers use to describe the directedness or “aboutness” characteristic of thinking and language. Consider, for example, Wordsworth's “Tintern Abbey”—“Five Years have passed, five summers, with the length of five long winters.” That poem is certainly about something, the ruins of an English abbey among other things. But not everything is. If a pen is attached to the end of a flexible tree branch that moves with the wind and manages over time to draw recognizable letters or words on the wall, there is no intentionality there. The scribbling isn’t about anything. Not only that, but there is no intentionality even if by some strange fortuity, the words that are drawn are the same as those that make up the first line of Wordsworth’s poem. In other words, if intentionality can’t be found in nature, because we’ve defined matter in a way to exclude it, how do we account for the intentionality exhibited by thought and language?

Further, what of the unity of consciousness, which is to say the sense of an integrated, simultaneous experience of life? I sip an orange juice at an outdoor café while hearing a train whistle blow in the distance with the air full of the scent of wisteria, and yet I experience these things as a unity, not as three separate, disjointed moments in time, like three separate frames in some sort of theater for the senses. However, how could some composite thing, made up of countless bits of mindless matter, create such a seamlessly integrated inner life? The terms “mind” and “consciousness” refer to all of these phenomena, and they seem difficult to account for in light of the mechanistic philosophy.

To oversimplify greatly, there are two main ways of dealing with these problems, materialism and substance dualism. The first, “materialism,” comes in a number of different varieties and essentially sticks to the mechanistic philosophy while either claiming that consciousness emerges from matter or by denying its existence altogether. The problem with the first approach is how one thing can emerge from another where there is a qualitative difference separating the two. To use one of Hart’s examples, one can see, given the characteristics of their constituent parts, how oxygen and hydrogen, when combined, creates water, even if water has different properties from the molecules that make it up. But it’s hard to see how anything that lacks intentionality and meaning could give rise to something possessing those qualities, no matter how many eons of random variation there might be. The problem with the second approach—treating consciousness as an illusion—is problematic for a different reason, which is that it involves denying the only verifiable reality we know while at the same time creating the not easily surmountable difficulty that an illusion itself would seem to require a conscious state.

An alternative to materialism is substance dualism, which also adopts the mechanistic view of matter. At the same time, however, it acknowledges the reality of qualia, intentionality, and other characteristics of mental activity. It just assigns them to a different substance entirely, what Descartes called res cogitans, or “the thinking thing;” in other words, the soul.

So, substance dualism leaves us with two different substances, body and soul. Most modern religious people, including Latter-day Saints, tend to think in these dualistic terms. This alternate solution, however, also raises questions. After all, how exactly are we to understand how these two ontologically distinct substances, mindless matter and matterless soul, interact to create the unity of consciousness that we experience? And are we really to believe that when we think, it is not the body that is thinking but some other thing entirely? And how can we be sure that what we’re thinking about is actually really out there in the world? How does this strange, ghostly thing called soul reach out as it were and penetrate a world wholly unlike unto itself?

What Hart does in this book is introduce us to an older, yet somehow newer and unquestionably stranger way of looking at nature. The appeal of materialism as opposed to substance dualism is that it’s a monism—meaning a theory of the one—and as Hart is fond of saying, “reason abhors a dualism.” That is to say, there is a tendency to reduce things to the simplest, most conceptually sparing principle. Philosophical materialism does this by reducing everything to matter, defined in a certain way. What Hart proposes is the converse: it is not matter that gives rise to mind but rather mind that gives form and purpose to matter.

This doesn’t mean however that there is some mind-like property of matter, analogous to mass or velocity for example, that when combined together in increasingly complex structures, like a human being, forms what we call the mental. For Hart, mind is less like the particles that make us up and more like the air that we breathe, a sort of vitalism pervading all things. It is the sun without which nothing could exist and by which we see all things.

Hart agrees that the mechanistic philosophy, reducing everything to material and efficient causes, has produced valuable insights and miraculous technologies. That said, he also agrees that a more complete description of nature requires resort to Aristotle’s concept of form and finality, rational relations giving structure and purpose to things. The examples here might include the prosaic, like trees with roots for the purpose of seeking out nutrients. But Hart points to thought itself as evidence of these rational relations, in particular the fact that we reason according to a particular structure of premises and conclusions rather than by exchanges of physical energies. And our intellect itself is oriented toward a pre-determined “transcendental horizon of values,” often conceived as the true, the good, and the beautiful, making it impossible for me to choose something bad at least as it appears to me. Language, as a “structural continuity of thought,” is also “a kind of formal causality, fashioning the material order ‘from above’” rather than arising from random non-intentional mutations. (264) What is true of thought and language is for Hart true of life more generally, where natural phenomena again exhibit structure and purpose, “limits as to ultimate possibilities as well as a disposition for realizing those limits.” (329)

One might be willing to concede these points and still wonder how Hart reaches the conclusion that mind is “a pervasive reality of organic life, at every level.” (338) Those in particular who are familiar with Aristotelian or Thomistic thinking might agree that life exhibits structure and purpose. But they would also probably say that’s different from saying that it exhibits the type of intentionality (that “aboutness” mentioned before) that one associates with mental states. In other words, maybe a tree does have a structure that allows it to seek nutrients, but, unlike a human mind, that structure and purpose doesn’t result in the tree thinking thoughts and writing poetry.

To this, Hart would respond that mind is a continuous whole and that while it might express itself differently and in different degrees of intensity in various parts of nature, it doesn’t admit of any sort of division. So, if form and teleology exist in nature, then that structure and purpose belong to the mental even though it might express itself differently in trees than it does in human beings. The resulting picture is of “the formal and final causality of mind shaping and animating organic life, and of organic life shaping and animating its material substrate—mind ‘descending’ into matter and raising matter up into itself as life and thought.” (339) For Hart, behind this picture is an eternal mental act, which itself is also composed of form and purpose, by virtue of which everything exists, “an original oneness underlying all things, knowing and revealing itself in the nuptial union of soul and world, and making itself known to us in the structure of all experience.” (459)

With this brief summary of Hart’s position, I’m afraid I’ve given the impression that the book is a systematic treatise. It’s not, and that’s actually what makes it so special. It’s a Platonic dialogue between four Greek Gods: Psyche and Hephaistos, the primary discussants, and Eros and Hermes, Psyche’s husband and friend, respectively. Psyche, the goddess of the soul, gives voice to Hart’s position whereas Hephaistos, the crippled God of craftsmen, takes the opposing views of materialism, dualism and panpsychism, with Hermes and Eros chiming in at times to support Psyche. This narrative structure is unusual but effective. Hart is at times an intellectual pugilist, and he can spar with the best of them. Although entertaining and funny, the combativeness sometimes gets in the way of the beauty and humanity of what Hart is always saying. Referring in his powerful book on universalism to those holding the opposite view as “infernalists” was fun but probably didn’t win Hart any sympathetic ears among his interlocutors (although he probably assumed, correctly, that that would be true even if he had chosen a less antagonizing label). In his wonderful book, Roland in Midnight, the main character, Hart’s own dog Roland, a brilliant canine philosopher whose real life analog sadly recently passed away, seemed to calm Hart’s fighting instincts. Here, the honor of that calming influence goes to the Gods and in particular Hart’s fondness for each of them. As we learn in the book’s introduction, even in Hephaistos’s thoroughgoing materialism Hart seems to find a kindred spirit at times. But most critically, the book’s dialogical structure allows for some truly beautiful passages. For example,

I believe that all that is has its being as, so to speak, one great thought, and that our individual minds are like prisms capturing some part of the light of being and consciousness . . . or, rather, are like prisms that are also, marvelously, nothing but crystallizations of that light . . . as is all of nature. (456)

And this:

I believe that this is the reality in which we live and move and exist, and that we enter into it at the beginning of life as into a kind of dream that was already being dreamed before we found ourselves within it, and that—from our first moment of being aware that we’re aware—our participation in that reality comes filled with both memories of the eternal and urgent yearning for the transcendent. All is familiar, all is impossibly strange. (456)

So, what does this all mean for religious types? It might be a bit challenging, frankly. Latter-day Saints and many Protestants (and frankly most modern believers) generally tend to think in terms of Cartesian substance dualism. Latter-day Saints often compare the body and the spirit to a glove and hand. The spirit is depicted as a separate substance, existing in the spirit world in a way similar to here on earth. At the same time, there is a fondness among certain other Latter-day Saints to refer to themselves as materialists. In this, they are probably drawing on Sterling McMurrin’s materialist picture of Latter-day Saint thought in his famous Theological Foundations of The Mormon Religion, as well as certain scriptures like Doctrine & Covenants 131:7, which says that “all spirit is matter, but it is more fine and pure.”

Of course, Hart rejects both of these alternatives. My own belief is that Latter-day Saint thought is neither materialist nor dualist, at least not of the Cartesian variety. I think that despite our way of talking about spirits, D&C 131:7 pretty much disqualifies dualism. Who knows what that verse means by the term “matter” (a notoriously difficult thing to pin down in light of its changing definition over time.) But whatever it means, it seems to point to a monism. At the same time, I don’t know why that monism has to be materialism. There are classical theists—those who believe that God is not a being but being itself—who are Christian, and thus they believe in an embodied God. In fact, Hart is one of them. Yet they’re not materialists, at least not in the modern sense. In other words, I think Hart’s position could be accommodated within Latter-day Saint thought.

A different question is whether Hart’s position is available to non-believers. Clearly a non-believer could affirm the possibility of something like Aristotelian form and finality in nature. Thomas Nagel, a philosopher who is both famous and famously atheist, has at least toyed with the idea. But what Hart is proposing is more than just the idea that thought, language, and life exhibit something beyond the type of causality affirmed by the mechanistic philosophy. He’s proposing that everything is part of an infinite mental act. Could one separate Hart’s approach to mind from his belief in God? I think so, because Hart’s belief in consciousness in nature isn’t necessarily dependent on his theism. Rather, he thinks that one can independently conclude that there is mind-like form and finality in nature simply by taking stock of things like qualia, intentionality, and the unity of consciousness. Whether there is also an eternal mental act requires a further conclusion that depends on classic arguments about how there must be some ultimate source of things that cannot be composed of parts. That conclusion may indeed follow from the first. But one could nevertheless fail to reach it for any number of reasons, and the first conclusion about mind-like form and finality would in that case remain intact.

Hart’s argument should be of interest to all. But is it convincing? At the end of the book, Hephaistos remains unpersuaded, as many readers no doubt will be. Yet he is at the same time moved by Psyche’s pathos and ready to move on with hearts in accord even if beliefs are not. My hope is a perhaps bolder one, that at the end of Hart’s book, even if we don’t agree entirely, we might nevertheless answer Emily Gibbs’s question to Wilder’s Stage Manager in the affirmative, that thanks to the picture Hart has rendered, we have realized life, and this time, while living it.

Zachary Gubler is the Marie Selig Professor of Law, Arizona State University, Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law.

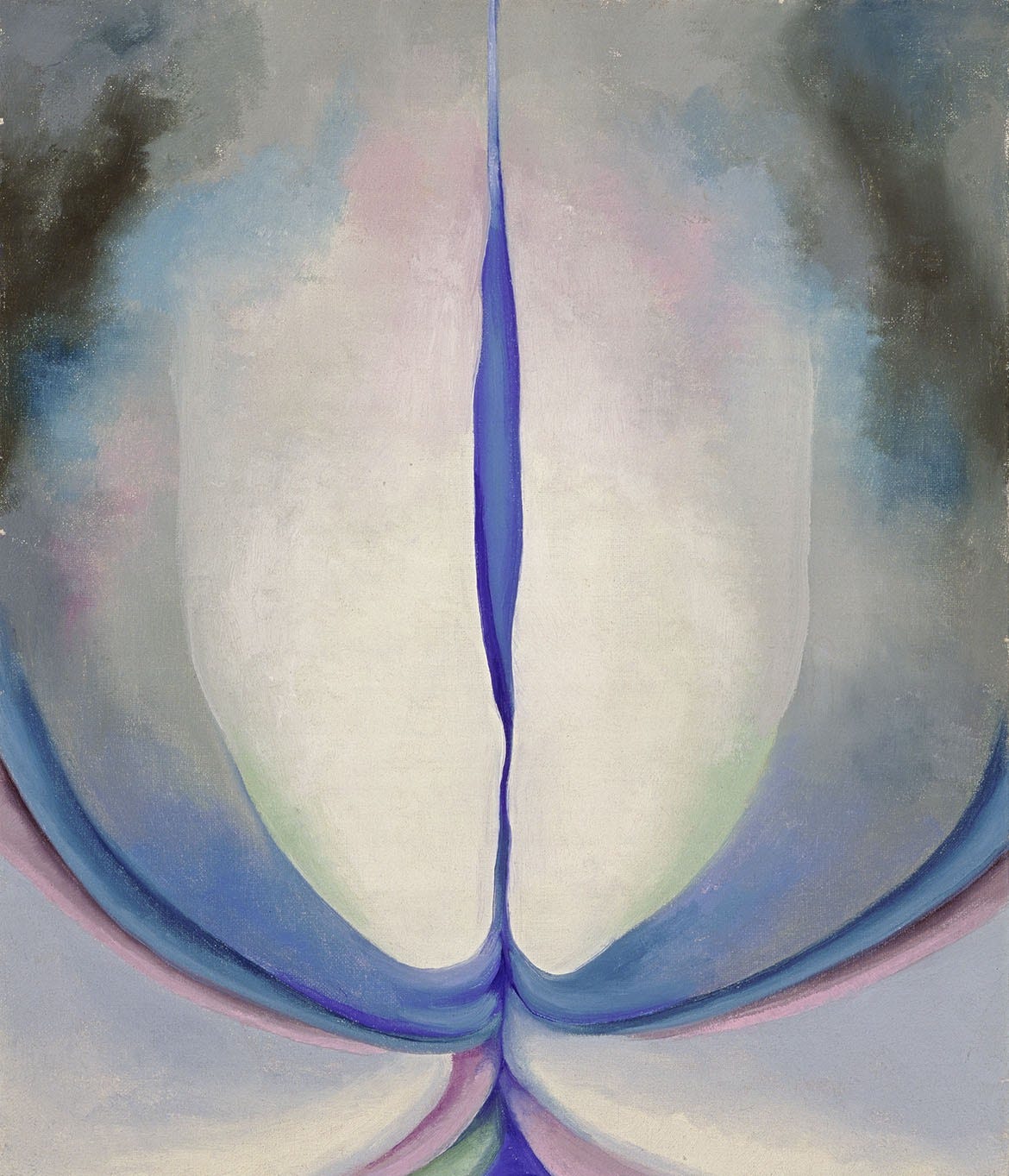

Art by Georgia O’Keefe.