Remembering a Wild God

Memory as a Source of Conviction

In the memorable speech that ends Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the good-hearted Alyosha proclaims, “There is nothing higher, or stronger, or sounder, or more useful afterwards in life, than some good memory.” In the face of family trauma, suffering, and death, he offers hope that “even if only one good memory remains with us in our hearts, that alone may serve some day for our salvation.” But while memory may be essential to redemption, it is also fragile and fickle. By it, we might be damned.

After law school, I worked for the Rocky Mountain Innocence Center (RMIC), an organization that investigates potentially wrongful criminal convictions in Utah, Nevada, and Wyoming. For about eighteen months, I analyzed cases that revealed the terribly painful consequences of memory’s weakness. I came to know and love people who spent many years in prison for crimes they did not commit because of eyewitness misidentification, which is the most common form of faulty evidence in cases of wrongful conviction.

I also carefully studied cases outside of RMIC’s ambit, including the poignant case of Jennifer Thompson-Cannino. As she describes in Picking Cotton, she mistakenly identified Ronald Cotton as her rapist despite having had an extended interaction on the night of the crime with Bobby Poole, the man that DNA evidence demonstrated was the true culprit. She recounts carefully reporting her memories to investigators shortly after the crime, feeling her memories carved onto her “like scars [she’d] never be able to cover.” At trial, she “couldn’t believe it” when Cotton’s attorney claimed the case was one of mistaken identity—“that [she] had been ‘stressed’ after the assault and couldn’t properly identify the man who had been lying on top of [her].”

But she berated herself later when evidence emphatically established she had gotten it wrong: “How could I have been in the same room as my rapist and not recoil?” she asks, reflecting on how her body responded viscerally and involuntarily to Cotton’s presence in the courtroom and reacted with nothing when she looked at Poole.

Cotton’s memory had conspired against him, too. When investigators first confronted him about the case, he provided a confident alibi only to later realize he had gotten his days mixed up. His explanation for the mistake on the witness stand sounded like desperate evasion in the face of Thompson-Cannino’s confident identification. But his seemingly weak testimony was reliable while her strong, sympathetic accusation was not. His prayers for revelation of the truth went unanswered until he was exonerated by DNA evidence in 1995, more than ten years after his conviction.

Thompson-Cannino’s case is an especially tragic instance of a general fact: We are not mere perceivers, recording mental video for precise playback when we later need it. As a popular history of wrongful convictions explains, “What happens in front of the eyes is transformed inside the head, and is refined, revisited, restored, and embellished in a process as perpetual as life itself.” Or as Andrew Bird puts it, “It's all in the hands of a lazy projector / That forgetting embellishing / Lying machine.” Both Thompson-Cannino and Cotton know the potentially profound consequences of this inescapable fact.

The stakes can clearly be high in court, so it shouldn’t surprise us if we feel deep anxieties when memory’s limits shape spiritual transformation. Given how much can go wrong when we recall and recount life-altering spiritual experiences, we should have a sobering sense of caution. But memory’s limitations might also have paradoxical strengths, at least from a certain theological perspective. Ironically, these potential strengths first appeared to me while reading Living with a Wild God, a memoir about memory and extraordinary experience by the antitheological journalist and writer Barbara Ehrenreich.

Before publishing the memoir, Ehrenreich was undoubtedly not a writer about spiritual experience. Her primary subjects were “the myth of the American dream, the labor market, health care, poverty and women’s rights.” But a set of bizarre experiences from her youth haunted her for fifty years, taunting and resisting her until her agent convinced her to turn a history of religion she was writing into a confession that addressed them head-on.

An unwavering and lifelong atheist, Ehrenreich resists simply labeling these experiences as “mystical.” But she reports that her vision, her sense of self—her entire consciousness—were transformed during recurring awe-filled moments that captured her without warning. And out of a sense of obligation to her future self, she recorded memories of them in journals she kept from 1956 to 1966.

In 2001, when faced with the prospect of death from cancer at age sixty, she gathered her personal papers for deposit at a university. But she could not part with those journals, which later became the primary source for the book. “I knew,” she writes at its outset, “the journal would require a major job of exegesis, a strenuous reconstruction of all that I once thought was better left unsaid.” And this exegesis could not be done by just anyone. Because these memories were hers alone, she was the only possible interpreter.

Here, I think, is the central power of memory. It is personal and proprietary. We are all the exclusive exegetes of our most personal experiences, and we feel the thrill of possession. But in our solitary exegesis, we experience both senses of that word. We feel owned by our memories as much as we feel we own them. Attempting to recover their treasures, we lament their incompleteness and corruptibility. And we have trouble explaining them, sometimes even to ourselves.

This confounding dynamic was certainly Ehrenreich’s experience. Aside from her old journals, she had never written or spoken about her strange experiences, which were in large measure unspeakable. She avoided even attempting articulation for fear of “sounding crazy.” Ehrenreich tells us most of what she wrote is likely accurate. What troubles her is what she left out. The first year’s entries offer just a few indirect allusions to “uncanny events” only she can decipher.

Nonetheless, she remembers “perfectly well” the first time “it happened,” roughly a year before the very first entry. While watching a horse show with her family on a Sunday afternoon, her fourteen-year-old self sensed “something peel[ing] off the visible world, taking with it all meaning, inference, association, labels, and words.” The experience began repeating itself occasionally, and she began the challenging work of interpretation. As she described the experiences in an early journal entry, “It is as if I am only consciousness and not an individual, both a part of and apart from my environment.” She couldn’t identify any material triggers for these weird episodes, so she concluded initially that they were the result of her perceptual faculties simply “falling down on the job.”

But as rational as this theory sounded, she admits, “I wasn’t ready to abandon the idea that [she] had gained a privileged glimpse into some alternative realm or dimension.” The empiricism of her determined atheism demanded that she keep this door open. “I had seen what I had seen—whatever it is that lies under the named world—and I was not going to deny its existence,” she writes. Looking back, she wonders whether she merited a psychiatric diagnosis such as dissociative identity disorder. But this didn’t work either because the experiences never impeded her daily functioning.

Ehrenreich didn’t realize how emotionally unsettling these extraordinary experiences were until the most significant one occurred during a walk in the mountains at the end of high school. With no apparent impetus, outside and alone, she found herself entering a new and more “radically dissociated state,” one in which she appreciated the mere fact that the air “parts before us without our having to resort to machete or shovel.” Mere movement was astonishing. And then, suddenly, “the world flamed to life” as she had “a furious encounter with a living substance” that came at her “through all things at once.” She didn’t lose control of herself, but she had no power to turn away. She didn’t feel euphoria, but she was captivated by a fearful intensity that lasted a few minutes.

Ehrenriech doesn’t recall how she returned to ordinary existence. “There is a gap here,” she acknowledges, but she recalls acutely how “the insane beauty of the morning had drained completely away, and what remained was not easy to look at.” Something had happened to her, not for her or her edification. “Paul’s blinding vision on the road to Damascus had come with instructions,” she writes. “My vision, if you could call it that, did not.”

In her first journal entry after the event, she reports, as she describes it in the memoir, an “emotional meltdown, unleavened by intellectual curiosity.” “I have lost my youth,” the entry reads, “The universe has no purpose. . . . Life is a joke.” Old Barbara acknowledges that her judgments of her younger self are harsh, but the brevity and self-pity of young Barbara’s account is maddening given what is at stake. “I feel,” old Barbara confesses, “like grabbing that useless girl by the shoulders and shaking her myself. What happened? What exactly went on in your head? Tell me everything even if it sounds crazy!”

And yet she acknowledges that young Barbara could not be expected to understand what happened and that her experience had been genuinely traumatic. The experience transcended the entirety of her understanding. The compartments of her mind were washed away as mysterious experience poured into them. Was there even a first-person from whom the original experience could be obtained?

This question points us to the first of memory’s paradoxical powers. We run up against its limitations in an intensely personal way that can teach us compassion for other selves. Our younger selves are intimately connected to our current selves, and by learning compassion for the weakness of our former selves, we can learn compassion for the weakness in others. Memory’s limits have the power to turn us outward as much as inward.

But for young Barbara, turning either way was a challenge. She knew no one, whether in her extensive reading or in her own life, who could relate. The one time she tried to speak about such an experience, she invoked the idea of God, foreign to her and yet the most accessible explanation. “I saw God,” she told a friend who had noticed her altered emotional state shortly after a ski trip, but immediately felt embarrassment and regret, “as if [she’d] been caught in an act of plagiarism or, more precisely, antiquities theft.” She pretended to have been kidding and said no more.

What had been shaken was not her atheism, but her sense of her surroundings. Part of the puzzle, she explains, was that “nothing unnatural or physically impossible had occurred, objects had not moved on their own, and the laws of geometry had remained in force.” She acknowledges the material and emotional factors that may have shaped the experience (e.g., low blood sugar or depression from recent social rejection). But reaching for reductive accounts of electrical states of the brain did not provide an adequate handhold on the terrifying cliff she was sliding down.

As the years passed, she kept her worries about the soundness of her mind to herself, and the frequency of her dissociative states diminished, as did her interest in them. She pressed on with college and the lab-life of a scientist. But her memories of the experiences always buzzed in the background, insisting that she was ignoring something important and irresponsibly abandoning her former self.

With middle age and motherhood, she felt a renewed interest in those old memories and found that seeking out accounts of similar experiences helped her begin to wrap her mind around them. This new sense of fellowship, not to say agreement, even led her to assert that her mental health likely would have fared better in the period just after her ski-trip vision if she’d had a religion in which to “house” the experience, a community with which to deal with the unfathomable. And while she would, with compelling argument, object to use of this acknowledgment as justification for belief in God, the acknowledgment is suggestive of another of memory’s powers—namely, the way it knits people together and focuses them on common causes.

Because the past always remains with us, we seek solidarity and understanding with those who have had similar experiences. And because we know we’ll need our past to forge our future, we deliberately create collective memories by taking family vacations or participating in religious rituals. We know memories attach us to one another and focus us on ideals and aims. We plan ceremonies like weddings to produce memories that will motivate and guide our actions.

Ehrenreich is, of course, decidedly opposed to forging a future with religion. But after years of meditation on the import of her visitations, she concluded that a capital-O Other—or, more likely, Others—are seeking us out. Not gods or ghosts, belief in which remained clear roadblocks to human flourishing in her view, but powers that animate animals, trees, and other life-forms of the universe. Whatever one might call this conviction (perhaps animism or neo-paganism), it is as firmly rooted in the natural world as it is in her early memories.

Here, we find yet more of memory’s powers. Memory gives us a sense of the preciousness of certain places and times. It ties us to the tactile and shapes our very sense of our surroundings. Something as ordinary as smell (a sense that, interestingly, does not feature in Ehrenreich’s memoir) can be intensely evocative of past eras and emotions. Hearing a few bars of a specific song can transport us to significant places of our past. And feeling the air and seeing the landscape of a significant place can remind us of the touch of a special person.

And yet, despite our familiarity with these powers, we fear, as we should, memory’s limitations. It tricks and haunts us, as it did Jennifer Thompson-Cannino, even when we handle it with great care. So how do we honor its powers while being realistic about its limitations?

William James, famed father of American psychology, offers, indirectly, a potential solution to this problem in The Varieties of Religious Experience. In that well-known book, which Ehrenreich praises briefly in the memoir, James encourages his readers to consider fruits, not roots. Forget searching for the truth of spiritual experiences, he argues. Focus on their tangible effects. Applying this approach to the limits of memory, we would abandon all quests for recovering original experiences and ask instead whether our ways of remembering them produce good fruit in the world.

This solution is attractive for its practicality and humility. We lack access to comprehensive recordings of our past, so why not concentrate on effects instead of accuracy? The trouble, I think, is that abandoning concern for truth leaves us with feeble means of assessing when fruits are good and when self-interest is corrupting our projects. Liars routinely justify themselves by invoking the primacy of outcomes over truthfulness, and good outcomes often depend on audacious truth-seekers (think of both the investigators in a case like Ronald Cotton’s and the scientists behind the DNA that demonstrated his innocence).

I think James and his fellow pragmatists are right when they assert that our memories and the beliefs that derive from them are not, to steal a line from Louis Menand, “a passive mirroring of the world, but an active means of making the world into the kind of world we want it to be.” But true as this may be, I wonder whether we should see memory’s inability to “mirror the world” as a paradoxical form of its power. In revealing our weakness and interdependence, memory’s limits can be a means of turning our hearts in genuine interest and compassion toward each other, our prior selves, and, as they did for Ehrenreich, toward the revelations of things, which can be stunning. When Ronald Cotton prayed for exoneration, for example, God disclosed the truth with DNA evidence, not a divine video of the crime.

Of course, we might also think about how memory’s limits can turn us to God as well. But if we see God primarily as an omniscient solver of our memory problems, an omnipotent filler of its gaps, we will lose sight of memory’s empowering limitations and the people and things toward which they turn us. Instead, we might see our inability to conjure the world anew in our own minds as a divine gift, a spur to seek connection to and revelation from the people and wonders outside of them.

In the Gospel of John, when Jesus prepares his disciples for his death at the Last Supper, he assures them that the Holy Ghost will “bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you” (John 14:26). But his instruction for remembering is not esoteric guidance for obtaining heavenly visions of his teaching. He gives them, instead, the ordinary task of regularly re-enacting their sacred meal together. In this simple ceremony that ties them to each other and to him, the joys of embodiment—taste and smell, the touch of a friend, sharing precious time—mix with recollection of an incomprehensible loss and love, and in this mixture, profound sorrow is honored while it is transformed. Memory is redeemed.

Perhaps, then, when we struggle to recover and relate to our past, we should try seeing our failures as a divine invitation to seek God in the minds of others and the marvels of creation. Maybe only then will we experience memory’s power to produce the wonders of heaven and, as Alyosha declares at the close of his speech, “gladly, joyfully tell one another all that has been.”

James Eagan is a songwriter who wishes he were a novelist.

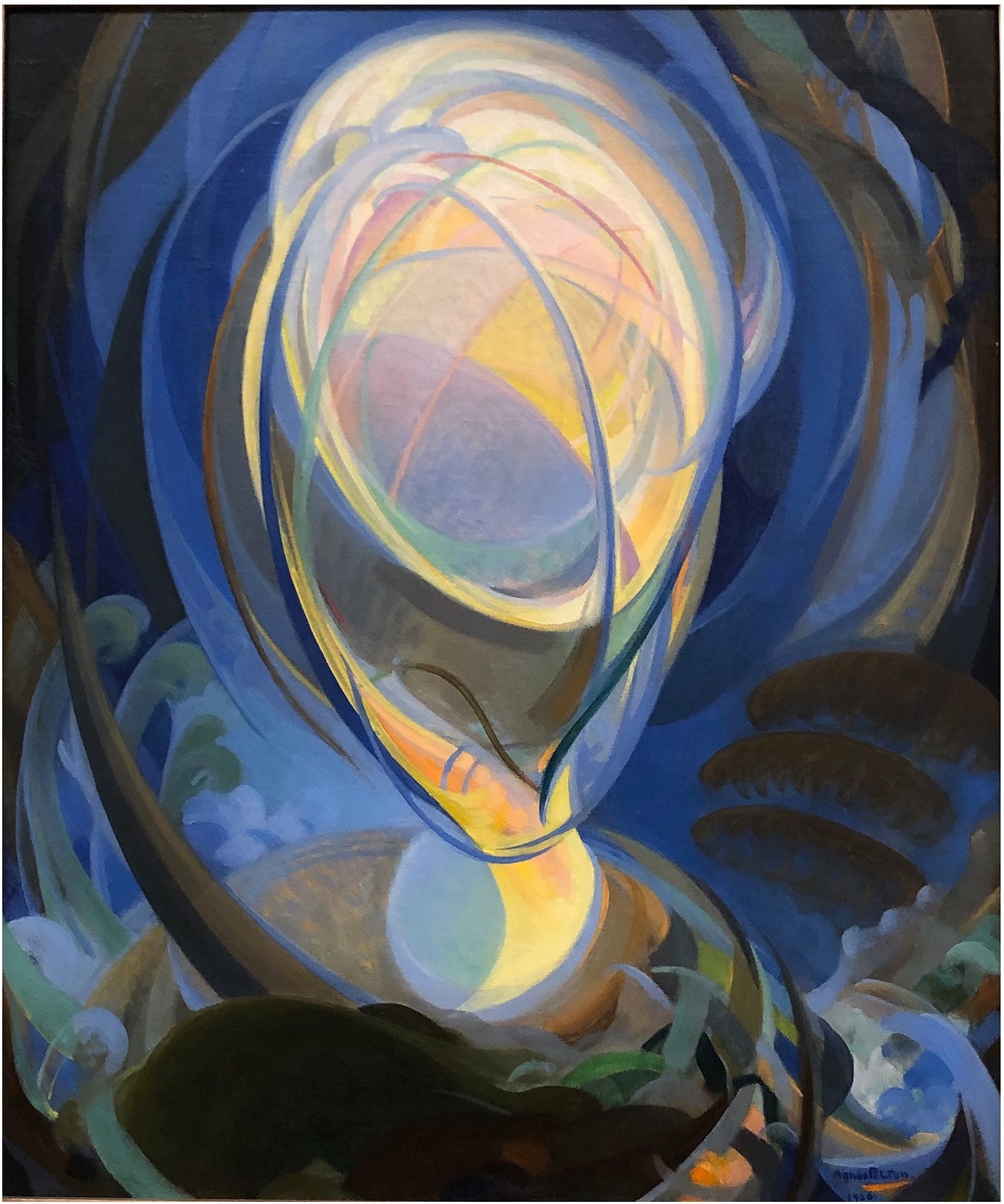

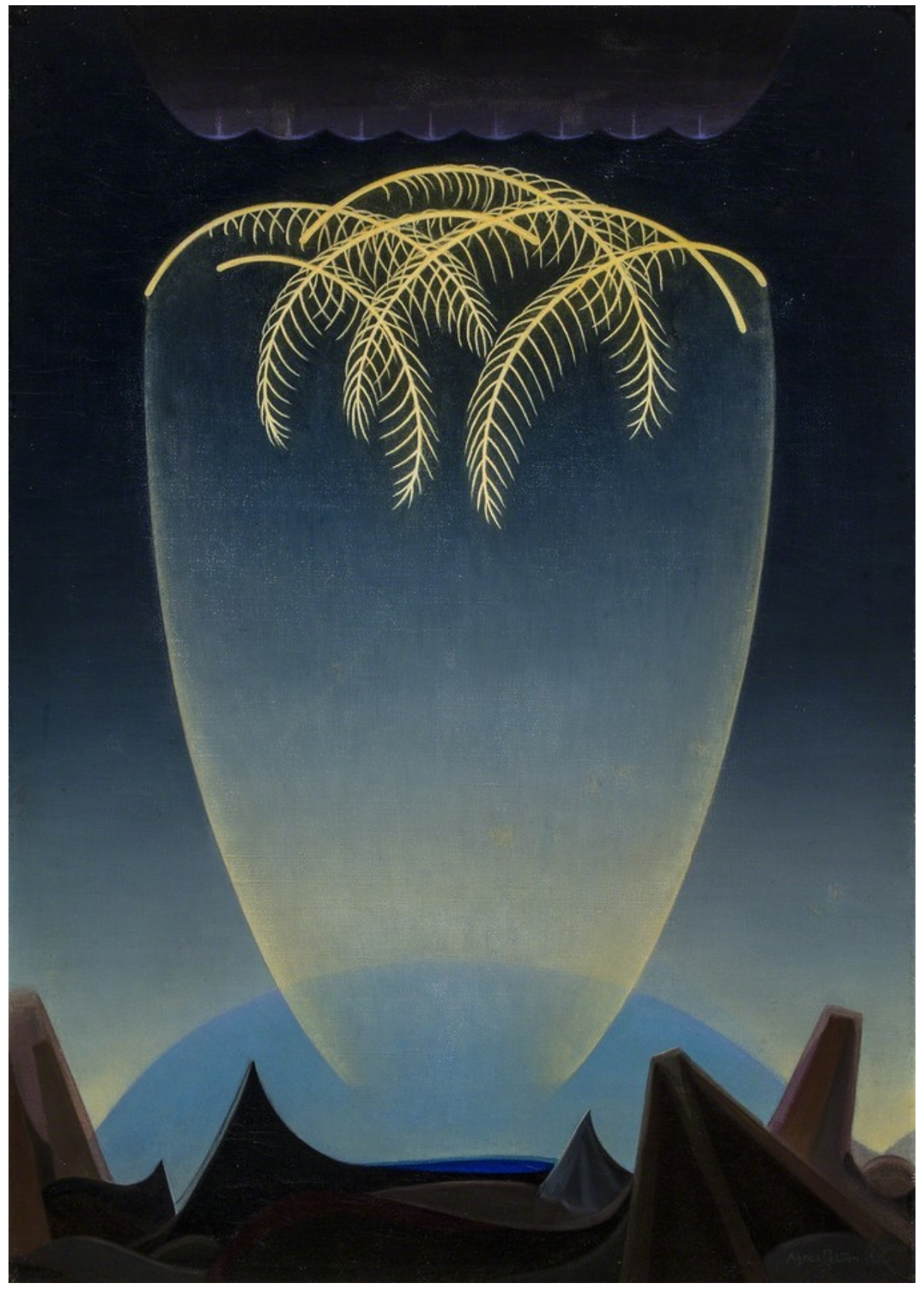

Art by Agnes Pelton.