Reflections on Father and Son

I’ve been reflecting on a few experiences that have helped me think through who I am as a father and who I am as a son.

This past summer, my wife and I baptized our third son as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For idiosyncratic reasons, baptism is one of the foundational experiences I have had as a child and an adult. Two baptisms in particular, separated by almost thirty years, helped me redefine and reorient a fraught relationship I have had with my father, who died when I was nine years old, shortly after my own baptism. In my adult memory, my baptism was an instantiation of all the ways that my Dad failed at his tragically short life. I don’t see it that way anymore. My first son’s baptism in 2016 changed that memory.

My Dad and His Life

There’s no other way to say it: Dad simply wasn’t very good at life, something I don’t ever remember not knowing. My parents divorced when I was five years old. My first memories of the world are all centered on him, almost always in some trauma that he was imposing. I remember so clearly the regular experience at ages six and seven, waiting for promised visits that never came. I would sit on the curb, studying the faded paint on my hand-me-down RC Cola backpack that doubled as an overnight bag, waiting for him to come get me for a Saturday night stay in his messy apartment. As the minutes ticked on, I would move farther and farther down the street in hopes of hastening his arrival. These vigils would last all morning but they often ended the same, with me coming in dejected and stood up. By the time I was eight, I had a lot of experience with Dad’s unreliability.

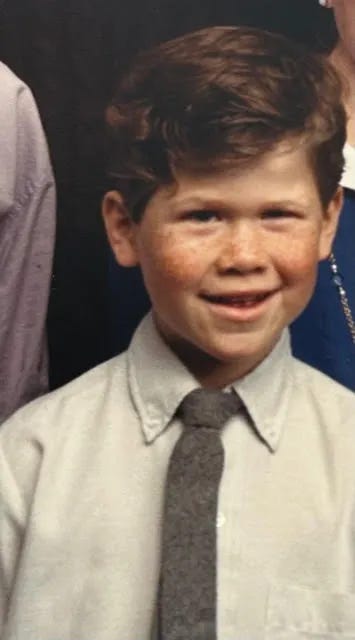

I also had unwavering devotion for him. He was, through it all, a hero to me on an epic scale. His laughter, a roller-coaster; his enthusiasm for life (when he felt it), my source of light. One night, at the end of a visit, my siblings piled out of his hatchback while I hid under a blanket in the back, hoping he would not notice until it was too late and I could stay with him. I was seven, roughly the same time as the picture above. (He discovered me as he was backing out of the driveway and took me back to my mother again, as I clung to his neck, sobbing.)

Some Phone Calls, Beyond My Years

In the summer of 1989, I turned eight, and it was time for me to prepare for my baptism. I wanted my Dad to participate in the second part of the ordinance, the “confirmation” that occurred during the regular Sunday church service. I knew that, as much as I wanted him to participate, the chance of his showing up on time and in a state to participate was remote. I needed a backup plan.

With my mother’s tender help, I decided to ask a neighbor to be my backup. He was a great home teacher. I would ask him.

Barely eight years old, I went to our rotary phone in my mother’s room and made some calls. First, to Dad. It was a hard conversation. I was shaking. I had never confronted him before. “I want you to confirm me,” I said, “but I know you might not be on time. Can you promise to be there?”

He was quiet a long time. I thought at the time that he was deliberating on my proposal. I imagine now that he was crying, probably struck by the poignance of the call and what it represented. He finally responded that he would be there and that I did not need to worry.

I was happy about this, but knew that he had promised before. My next call, then, was to our home teacher. “Hi, Brother Weir? This is Peter Brown. I want my Dad to confirm me tomorrow, but he might not come. Will you confirm me if he doesn’t?”

He graciously agreed. Finally, a call to our bishop, who would be conducting the church meeting. To give my Dad a fighting chance I wanted the bishop to subvert the usual alphabetical ordering of confirmations—about ten kids were baptized in all, a bumper crop in our congregation that month. Every minute counted in my mind, and I knew that going as late as possible was the best chance my Dad could have.

“Hi, Bishop Allen? This is Peter Brown. I want my Dad to confirm me tomorrow, but he might not come. Brother Weir will do it if he can’t make it. Could I get confirmed last to give my Dad more time to get to church?” He readily agreed. A comforting memory seared into my mind from that day is hearing the Bishop announce the other confirmations in alphabetical order, but with Peter Brown announced last: “We’ll proceed in that order,” he said with love in his voice, giving me a knowing look from the pulpit.

Dad made it. I can’t remember if he was late, but I remember feeling so much love for him as he kept his promise to me.

He died not long after that day. For many years thereafter, the picture of the two of us taken that day, me beaming up at him, hung on my bedroom wall. It was a treasured memory.

A Happy Memory Turns Bitter, Courtesy of Some Bad Plumbing

Until it wasn’t. I had not thought much about that day until it all came back to me as I prepared to baptize my first son. At the time, our somewhat geriatric church building in Pennsylvania had a serious limitation: you simply could not get hot water for baptisms. A friend explained to me that the theory was to prevent scalding, but the reality was to prevent it from being warm at all. Frigid water came quickly, lukewarm water came at a trickle. In December, the time for my son’s baptism, this scenario was not a good one for my son, who had already said that his only concern about baptism was the frigid water.

I strategized what I could do besides telling him to buck up and remember the Mormon pioneers. I came up instead with a plan. I arrived at the church on the morning of his baptism at 4 am to start a little ecosystem of multiple pots boiling water in rotation on the church’s two kitchen stoves. The pots ranged in size from a little tea kettle (it boils water in about five minutes) to a monstrous lobster pot (that took 40 minutes to boil). For hours, I paced between the font and the kitchen with these pots of boiling water, each one a latent calamity, topping off the frigid 2/3 I had already filled, running against the clock to make the temperature as pleasant as possible for my little boy.

As I paced the hallway with those cantankerous pots, I remembered the morning of my confirmation. The contrast between me as a father and my own father became a bone in my throat. I kept picturing my young self pleading for my father’s presence in my life, sitting on the curb waiting in vain for him to come and having that hard phone call with him to beg him to keep a simple promise. Realizing I coordinated well beyond my years to cover for a man that everyone knew wasn’t measuring up. I stifled tears as I huffed through the dawn hours, thinking of what I had lost in those years as a son who longed for some effort, any effort, from a father who seemed unwilling or unable to give it. That memory cast a gloom on an otherwise beautiful day.

My plan to heat up the baptismal water worked. I won’t say the water was warm—my son said, with enthusiasm, that it was “not unbearable”—but it was not frigid. I carried that water because I love him with a deep visceral love that I have felt all of his life. But perhaps more importantly, I carried those pots because I find acting on that visceral love very easy to do. That love for the Conti-Browns as a husband and father was my guiding light that day and remains my North Star now.

A Healing Theophany

That night, as Nikki and I processed the sacred majesty of the day, I told her about the painful contrasts with my father that harrowed my long morning. Though she never met my Dad, she knew these stories and could help me understand them better than anyone else. As she listened, something she said made me sit up. As she had been many times before, she was the vehicle for a beautiful theophany.

“I guess we will never know what pots of boiling water your father carried to get to you that day.”

Few moments in my life have impacted me more. My father had deep, life-altering depression. For all I know, encountering the phone call that reminded him of his failures and making it to the church on time was an act of profound love, perhaps more heroic than heaving that lobster pot into the baptismal font. In that special moment, instead of resentment at and longing for a lost childhood, I felt only love.

Love for my mother and her steadiness through those years of anguish.

Love for those wonderful Latter-day Saints who carried my family through death and divorce and poverty and took me so seriously, so gently, during my day of need and celebration.

Love for my wife and for the Conti-Browns, this new family we created and pledged would be different from what had come before.

Love for God and the church that has become a focal point for my family’s identity, a common language to understand our obligations to each other and to the wider world.

And in the moment of clarity, I felt love even for Dad.

Weak Things Become Strong

There is a verse in the Book of Mormon that is often cited in Latter-day Saint meetings. It is in Ether 12:27, a declaration that if we bring our weakness in humility to God, He “will make weak things become strong.”

My Dad was, through all of my life and most of his, weak by any objective measure.

On that crisp and freezing morning in 2016, as I heaved those pots of boiling water into the baptismal font, I saw in real time one father’s weakness becoming another father’s strength. Whatever else my flaws, that morning I was strong for my boy. He didn’t have to worry about frigid water ruining his day because, though in so many ways I’m the same vulnerable person with the RC Cola backpack, that day I would do what a father needed to do.

Just like my father had done before me. Weak things had become strong indeed.

Peter Conti-Brown is the Class of 1965 Associate Professor of Financial Regulation at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Art by Colby Sanford.