Martea stared down the tracks waiting for the bullet train that would bring her sister into the desert. The high sun meant that the valley floor had no shade from the surrounding mountains. Even her loose white dress couldn’t keep her from sweating. Sensible people would be resting at home in midday, but the cross-continental trains didn’t wait upon local tradition.

She shifted to find some relief in the shade from the station building, but its arched organic structure provided little, though it did let the breeze from the Second Great Salt Lake pass through, bringing not cool air but a fishy, salty smell that reminded her of the ocean of her home. Sometimes in the height of desert summer, Martea longed for the cool of the dappled sunlight under the redwood trees surrounding her parents’ house in the Jefferson Republic, on what had once been the California coast, but she knew she wouldn’t trade this mountainous desert for anything. New Zion was more than just a home; it was a calling, a state of mind, both spiritual and ecological.

Just when she thought her eyes would give out from keeping watch, the silvery train appeared around the corner of the western mountains, slowing down gradually from the unimaginable speed that had brought it across the Nevada desert.

Martea straightened her wide floppy hat, steeling her nerves. Had inviting her younger sister here been a terrible idea? They hadn’t spoken since the day when Martea had packed up her bag at age sixteen, following through on her commitment to the missionaries. Nine-year-old Lilianna had stared out the front window as Martea had walked away, leaving the idyllic community her family had helped found on the Jefferson coast to help forge a new community in the ruins of what had once been the Salt Lake Valley.

Once the hypercom satellites were repaired at the end of her second year in the valley, they could have spoken at any time. And yet they hadn’t. Martea’s first comms on the new system—at first cheerful and celebratory, then cycling through anxious, impatient, pleading, and furious—had pinged back unopened. Her family must have still been mad about her conversion. If she had thought that years of worry about his daughter living in a desert wasteland would change her father’s feelings, she was sorely mistaken. Gradually, her hurt had metastasized into anger. Why couldn’t they put their opinions aside and just accept her new beliefs? Didn’t they know how hard it was for her to leave them? Why couldn’t they understand?

Martea thought she had buried her feelings toward her family, pushing them down where they couldn’t interfere, but it all came erupting out when a comm from her younger sister Lilianna appeared in her commlog last spring, telling her that their father had passed away. She wanted to refuse to answer, to sling back some of the rejection she had felt for all those years, but she made the mistake of showing the message to her husband.

“Sounds like a flag of truce,” he said, reading the message over. He didn’t see all the little slights she saw in the message, the implication that the broken relationship was her fault. Nonetheless, he told her, a relationship had to start somewhere. His encouragement, plus a Sabbath sermon on forgiveness, pushed her into answering and arranging this meeting.

Someone had to make the first crossing of the divide. And it was too late to back out now.

The train reached the station and settled to a stop like a migratory bird landing on the nearby lake. The false noise of the electric motor shut off. The doors finally opened. The crowd began spilling from the train like cotton flying from the cottonwood trees in early summer, wearing so many styles of clothing that it seemed like a miniature Assembly of the Unified States. Would she even recognize her sister among all these strangers?

Then she saw a tall woman with sandy blonde hair, who looked like a stretched-out version of the nine-year-old she’d climbed trees with. Around her neck was a long blue turquoise beaded necklace, the one her father had bought for each of them on a summer trip to Cascadia. Within her, she felt a rush of tenderness that she hadn’t felt since leaving Jefferson, and almost without thinking, she waved her arms frantically over her head, shouting her sister’s name in pure joy. “Lilianna! Over here!”

“You’re pregnant?” Lili hadn’t thought through what might have happened to her older sister in all those missing years, but she certainly hadn’t expected her to be pregnant. But as Martea pulled her into a hug, the swell of her abdomen was undeniable. She pushed back and looked into Martea’s eyes.

“Yes,” said Martea, her face beaming, “I’m due in a few months.”

“That’s wonderful,” Lili said. “I can’t believe you’re going to be a mother.”

Marta glanced over toward Lili’s bags. “Well, I’ve been a mother for a while,” she said. “This will be our third.”

“Third?” Lili immediately regretted the shock in her question. Obviously, their mother had taught her better manners than to comment on other people’s life choices, but three children? Especially out in the desert. She knew that New Zion was a very different sort of place, but in the Jefferson Republic, people had thought it was unusual, and maybe a little wasteful, that Lili had a sibling at all.

Lili wondered what other surprises were in store. Martea had said so little about her life in her reply to Lili’s comm. Lili knew her sister was married because she’d struggled to find her in the comm directory before discovering that she’d been so old-fashioned as to change her last name. Still, somehow, Lili had imagined that her older sister would have stayed the same person who used to read her bedtime stories as their house rocked slowly in the canopy. But she couldn’t assume anything.

Lili tried to reset: it had been her idea to try again to contact Martea after Dad died. Mom hadn’t thought it was a good idea, but Lili really just knew that if anyone could reach her sister, she could. Maybe that hope was childish, an artifact of the age Lili had been when Martea left. She straightened her button-up shirt and shorts and mustered a cheerful voice even though she was exhausted from the train ride. “It’s good to see you again! I go by Lili now though.”

“Oh yes, Lilianna is much too babyish,” Martea teased. “And now you’re all grown up! I can hardly believe you’re here.” She picked up one of Lili’s bags—Martea insisted even though Lili said she couldn’t possibly make her pregnant sister carry anything—and pointed down one of the hallways. “The sand-crawler line is this way.”

Lili dutifully followed, gazing up at the strange cavern of the station. She felt as though she were inside a termite mound. The light filtering down from the various holes felt strangely like the light on the forest floor back home, yet somehow wrong: all orange and yellow instead of green.

“It’s built with sand,” Martea called from several meters ahead. Lilianna realized that she had stopped to stare at the ceiling and rushed to catch up with her sister. “The engineers inject bacteria into the dunes in a certain pattern to harden the sand into usable shapes. Then we cement them together into these buildings.”

“But if you could pick any shape, why so many holes?”

“For passive cooling, and of course it makes the building less disruptive to the ecosystem.” Martea continued on, eagerly explaining all the features of the building with an enthusiasm that struck Lili as forced. She felt sorry for her sister having to live in this wilderness. How could you have an ecosystem in this treeless valley? What were the animals supposed to eat? Where would they live?

Lili thought that coming here she would understand Martea’s choice more, but she was more baffled than ever. Why live in a place like this when you could have the bounty of the Jefferson Republic or Cascadia to the north? Why had her sister chosen this place, this people, over her home?

And now she sounded just like her father, resentfully opining over Martea’s betrayal as he had done for most of Lili’s life. At the memory of her father, her hand went unconsciously to the necklace. She started wearing it regularly after his death. Even though it was just an inexpensive souvenir from a family vacation, wearing it felt like a part of him was there with her. Lili almost left it at home when she was packing. After all, the force of his character was what had kept their family apart all these years. Yet somehow it felt right to bring him with her, crossing the desert he had refused to cross in life. His feelings towards his wayward daughter had never really matched the rest of the person Lili knew. He was kind and gentle, always leaving out food for the wild animals when it had been a particularly hard winter. Maybe he would see what she was doing and understand.

Finally, they arrived at a larger aperture in the porous structure, which opened out on a field of strange boat-like vehicles, their treads resting atop the sand. The whole vehicle made her feel uneasy. The treads reminded her of the tanks she’d seen in school videos showing political conflicts of the Before. The sand-crawler was crowded with other people leaving the station, and so her conversation with Martea died down to situate Lili’s bags on the luggage rack.

With a jolt, the crawler began to pull out of the station. Once it was going, the ride was smooth, and Lili watched the landscape outside go by. The openness was strange to her—where were the trees? A bowl of mountains surrounded the desert, letting her see the work of reclamation going on in panorama around them. Large swaths of suburban tract houses, once identical, now stood in various states of disassembly, gradually being replaced with domed structures of clay mud. The old downtown skyscrapers stood covered in solar panels and turbines.

And in the center of it all, a stone temple, its six spires surrounded by greenery growing on the roof.

The sight of that temple hit Lili like a slap in the face. The forest on top made it seem as if the temple had emerged fully formed underneath the natural landscape, pushing its way out of the ground to change everything. She had known little about the Mormons until her sister had become one. Mostly just some footnotes in the old history books written about the Before. She hadn’t really paid attention, thinking that she’d never meet one in the now-fragmented assembly of states that had replaced a once-united country. Then seemingly overnight, all her sister could talk about was New Zion and gathering the people and living in harmony with man, nature, and God. Most of it had gone over her head. She was only nine at the time.

But she had understood the yelling between Martea and her parents. At first, their discussions had been long nights filled with logical arguments about things like angels and prophets, but as Martea had become more and more interested in the religion of the two young strangers, it had devolved into shouting that carried through her bedroom door. Oh, the words like “oppressive” and “patriarchal” she’d had to look up later in the dictionary. But she’d understood when the door slammed that final time—her sister was leaving her.

Leaving her for this granite temple.

As the crawler turned to trundle southward, a silence sat between Lili and her sister that she didn’t know how to break. How do you start a conversation with someone who you once knew inside-out who has become a total stranger? Out the window, Lili saw only desolate wilderness and hardship. How could she pull her sister back from this desert into a world that made sense?

From her sister’s wide eyes, Martea could see she was impressed with the progress that had been made at restoring the valley. The changes spoke for themselves, so she felt she hardly needed to say anything, though she tried to explain some particularly interesting technical aspects of the reclamation. When she had arrived in the valley, the work was just beginning. The air was still full of poisons from the dried lakebed of the First Great Salt Lake. People often wore masks as they worked on the massive construction projects. After years of backbreaking work to redirect the rivers and conserve rainwater, the lake had begun to refill, and air quality improved drastically. She smiled thinking of how the desert was blossoming again, but this time as a sego lily instead of a rose.

Finally, the crawler reached their stop. After climbing down to the platform, Martea pulled out two of the communal electric bikes racked up nearby to get them the last miles to her home. Her belly was still small enough that the ride wasn’t cumbersome, and she enjoyed the air rushing past her face.

On the way, Martea led them past their neighborhood rainwater catch. Lili seemed to listen as she explained how the land had been sculpted into low swales that allowed the dirt to draw water up to the ridge above. “This whole greenspace requires no irrigation at all. We take the kids on picnics here on Sunday.”

Lili said it was nice, but she eyed the five-foot trees surrounded by low bushes skeptically. Suddenly, Martea saw the little park through the eyes of someone used to the lushness of the west coast. It made her want to keep explaining, to force her sister to see the beauty in her arid ecosystem. Lili couldn’t see all the work Martea had put in on the work crew sculpting the barren soil, all the composted nutrients they had carefully fed back into the dirt to replace those leached out by years of lawns and artificial fertilizers. Just because the scrub oak and sagebrush were less green than the ferns and moss of the redwood forest didn’t mean they were worse. They just took a different eye to appreciate.

Martea’s vegetable garden evoked a much better reaction.

“You can grow food here?” said Lili. She dropped her bike on the sidewalk in her rush to see the abundance in the front yard of Martea’s half-converted suburban house.

Martea laughed. “How did you think we lived here? Imported food like the old days?”

Lili was on her knees examining the soil. “The ground—It looks like a waffle!”

“It’s a technique we adapted from the Pueblo tribes to the south. The low mud walls direct the water towards the plants’ roots, holding it in the gravel while it soaks in.” Martea picked a cherry tomato from one of the vines and handed it to her sister. Lili sat back on her heels and popped the tomato into her mouth, but almost choked on it when Martea added, “The church put out a booklet a few years back on how to run a sustainable family garden. Almost everyone has one now.”

Distrust immediately flashed in Lili’s eyes. Martea kicked herself for bringing up the church, but she wasn’t used to having to dance around the subject. It was just a fact of life in New Zion. Sure, there were some settlers in the area who weren’t Latter-day Saints, but after most people fled during the Great Climate Crisis, those who had returned were largely Latter-day Saints on ecological missions. By and large, the church had directed the reclamation of the land. Some people didn’t like it, wrote newspaper articles claiming it was too much like the governments of the old times telling people what they could and couldn’t do, but a massive project requires massive coordination.

This was what Martea’s father had never seen: the miracles that could happen by working together. Sure, you had to trade some of the independence that was his most prized possession, but she did it willingly because she believed in the cause. In places like the Jefferson Republic, there was plenty of water and wildlife; each family could operate autonomously. But in the desert, without coordination, water wouldn’t be shared fairly. Wasn’t that what had happened in the old American states—everyone taking more than their fair share out of the communal water table until none was left? The Colorado River was still recovering from the damage done by allowing it to be bled dry. Only by coordinating with each other could they live in harmony with the land.

Her father had only seen the restrictions and the sacrifice, never the beauty.

The door to the house creaked open, and Nelson and Camille came bounding down the steps, so excited to meet their long-lost aunt that they nearly tripped on the reclaimed cement path. Martea just managed to grab their hands to prevent them from bowling Lili over. Honestly, they had practiced this whole thing with the kids last night, but of course it all went out the window now.

Lili stood up from examining the zucchini that sprawled across the yard. “These must be your kids!”

Confronted with the actual reality of an aunt, the kids suddenly became shy, pressing themselves against Martea’s skirt. She sighed as she crouched down to coach them, “This is your Aunt Lili. Say hi.”

Nelson recovered first. “Hi, I’m Nelson. I’m five.”

But Camille wouldn’t unbury her face for anything and started whimpering until Martea was finally forced to pick her up. “This is Camille. Can you show her how old you are?” She shook her head, rubbing the tomato sauce on her face all across the white fabric of Martea’s dress. “She’s two, and not normally this shy. Usually they’re all over the place.”

“Yeah, I can’t keep up with these two,” said Devin, coming out the door and down the concrete steps. “I honestly don’t know how you do it every day.” He put a hand on Martea’s shoulder and gave her a quick kiss.

“No doubt in a month or two I won’t be able to. Luckily, they’re both my good helpers, aren’t you?” She tried to coax Camille out again and this time succeeded in getting her to peek at her aunt.

“So . . . you stay at home with the kids?” said Lili.

Martea resented the judgment behind the question and shifted Camille to her other hip. “It’s not like the old days. Everyone works at least a few shifts a week, reclaiming sustainable farmland or converting more housing for the new arrivals. But yes, I’m primarily responsible for raising these little crazies.” Just then, Camille, who seemed to have gotten over her shyness, reached out to grab the tempting blue strand of Lili’s necklace. “No, honey, that’s not for touching. Run along and play.” Martea sat her down and the little girl ran off after her brother. “Anyway, Devin does more shifts than I do, plus he’s the stake executive secretary.”

Devin shook Lili’s hand. “Martea’s told me so much about you two growing up together.” Martea thought about how most of what she had told him had been colored by resentment, but Lili needn’t know that.

Lili looked perplexed. “It’s nice to meet you, Devin. What’s a stake executive secretary?”

“Oh, sorry,” said Martea. “It means he’s in charge of making appointments for the leaders of our local group of congregations, kind of like an administrative assistant. It keeps him busy, but we manage.”

This explanation didn’t seem to alleviate the confusion on Lili’s face, but just then the kids rushed through, screaming and shouting, playing some sort of game. They nearly knocked Lili over as they galloped past and into the house.

“Woah,” Lili said. “Are they always this excited?”

Devin laughed. “It’s not every day you get a new aunt, I guess. Here, let’s get you upstairs before you get trampled.” He grabbed Lili’s bags and began to escort her upstairs.

But Martea was frozen in the front yard, reminded of all the childhood games she had played with Lili, the times they had threaded themselves through the woods just as recklessly, free and unhindered by considerations of the difference in their ages. How had she gone so long without thinking of those days? Her heart wanted that unthinking childhood friendship back, but maybe it was impossible. Maybe the difference between them was like the slot canyons to the south: a gap so narrow yet separating two parallel walls going on forever.

***

Lili unpacked her things into the drawers of the guest room one by one, taking up as much time as possible so she could pull herself together. She was happy that her sister had found someone to spend her life with and that her kids seemed happy. And she really hadn’t expected to find her sister’s life to be so good. All her childhood, she had imagined Martea trapped out here in the desert. It was the picture her father had painted for her: how sad it was that Martea gave up everything they had given her.

Now being here, none of what her father had taught her to expect was true. This desert life seemed to suit her sister. She seemed so proud of all they had built here. The truth was that Lili didn’t fit in Martea’s new life. Even though she hadn’t been around her sister in thirteen years, finally being here brought their differences into focus. She had anticipated spending time with Martea, reminding her of their childhood, but now no doubt all the busy-ness of her family would be in the way.

And that wasn’t even starting on his new religion: How could a religion change her sister so drastically? It changed her into someone completely different, with a whole new web of connections and purposes that Lili couldn’t be a part of. Martea’s family should have been part of Lili’s life, and all she wanted to do was run back to the shade of the redwoods.

She took a deep breath and let it out. She would get through it. She needed to get through it. They would figure this out, and then Martea would be back in her life again.

Her things neatly squared away, Lili walked downstairs and saw the kids through the backdoor continuing their running game, leaping over imaginary obstacles. Clanking and bubbling noises let her know that someone was in the kitchen preparing dinner. There was a strange smell in the air that she couldn’t quite place: something savory like mushrooms but more so. What was it? She came through the kitchen door in time to see Martea pulling something out of the oven.

It was a roast.

An honest-to-goodness dead animal.

Lili stood frozen, her mouth hanging open. Martea turned around and saw her. The explanation started to come pouring out of her sister’s mouth, but the calm, patronizing expression on Martea’s face snapped Lili out of her shock.

“You eat meat now? And you didn’t tell me?” Everyone in the Jefferson Republic was vegetarian. Martea had been a vegetarian. Their whole family was vegetarian. “Is this part of your new religion now too?”

“Don’t worry!” said Martea. “I’ve also got curried cauliflower and plenty of pasta. You’ll be okay.” Her tone of voice sounded like she was calming an unreasonable child, and it grated on Lili. “I’m sorry I forgot to tell you. I’ve gotten so used to everyone eating meat that I didn’t think to mention it in my comm.” Martea sat the roast down on the counter and wiped the sweat from her forehead, looking exhausted.

The words escaped Lili’s mouth before she could stop them. “How could you just turn your back on all we stood for?” She didn’t know where she was going with this; anger pulled the words out of her brain before she could think. “How many cows have to die to feed you people? And all the methane—”

“What do you mean by you people?” said Martea, suddenly closed off.

“You know what I mean. The missionaries, the Mormons, all this—” she gestured at the whole of the desert kingdom that had swallowed her sister. Immediately after she said it, she knew she had gone too far.

Martea’s voice was eerily level. “Just because I’ve chosen something different doesn’t mean I’m a bad person.”

Something in Lili’s head knew this was logically true, but she found herself shouting back, “Dad was right. You’ve been brainwashed. Why would you let them take you away from us? Away from me?”

And then she turned and ran out the front door into the yard where the sun hovered just over the mountains, that continental divide between her home and Martea’s. Her feet pounded down the path, turquoise necklace bouncing against her chest. She gradually lost momentum as she realized she didn’t know where to go. She paced slowly back, sat down on the ground on the farthest corner of her sister’s yard, as far as she could get without being lost in this strange desert, wrapped her arms around her knees and cried like the nine-year-old she used to be, crying alone in her treehouse for a sister that never came back.

That could never come back.

***

After dinner had been served to the kids, after their questions about where Lili had gone were brushed aside, after they had been set on their homework and Devin had started on folding the laundry, after blowing out one last deep breath, Martea gingerly opened the front door. There was Lili, sitting on the salvaged chairs on the front porch, her face red and streaked but not actively crying.

Lili looked up. “Sorry.” She wiped her face with her sleeve and mustered up something that was almost a smile. “I just can’t believe you’re not vegetarian anymore. I thought that even with all the . . . changes, we would at least have that in common.” The catch in her sister’s voice belied the reasonableness of her words.

“It’s my fault. I should have given you more warning.” Martea walked over and reached out for a hug, and Lili stood up and obliged.

She couldn’t tell which of them started to cry first, but that embrace broke some sort of dam, and soon the sobs racked both their bodies with all the things that had gone unsaid for thirteen years. They clung to each other. It felt good to squeeze her sister, even with her pregnant belly between them. She had forgotten how it used to be, when Lili had come to her in the night woken by the howl of a coyote. Or when she had come to Lili, heart broken by some boy at Secondary.

Once they were cried out, they sank down into the porch chairs, looking out towards the west, the darkening blue of the sky with the outline of the mountains still just visible. Martea could still remember how strange it felt to be able to see so far across the valley from anywhere, when she had still been used to the dense tall forest that had been her world for so long. She had felt small and insignificant, and at the same time part of something greater, the way she had felt about her faith when she had first found it.

“I know Dad always thought I was making a mistake coming here,” Martea said. She didn’t look at her sister, afraid that she wouldn’t be able to say the hard things if she did. “He fought hard to get me to stay, told me that I was brainwashed, that I’d regret my decision.”

“He always said you’d come back eventually, but you never did,” said Lili.

Martea sighed. “Look, I don’t expect you to understand why I believe what I believe. That’s all fine with me. But I hoped that someday he’d see that I had to follow what seemed right to me. Isn’t that what we believed most of all? In doing what’s right?”

“I suppose,” said Lili. “But was it right to leave your family behind? I just—I miss being able to understand you. We used to share everything.” She twirled the turquoise beads of the necklace between her fingers. Their father’s necklace.

All of a sudden, Martea could see that this wasn’t really about her beliefs and whether their father had poisoned her sister against the choice she’d made. It was about the relationships she’d lost when she made that choice. She thought about that trip where her dad had bought those chains of turquoise from a roadside shop. “Whatever happened to my turquoise necklace? I think I left it when—I couldn’t bear to look at it.”

“Actually, this one is yours.” Lili lifted the necklace over her head and handed it to Martea. “He kept it hanging on your door. I passed it every day. Mine is in my suitcase upstairs.” The smile in Lili’s voice faded. “He was stubborn, but I think he still cared about you, even if he was pigheaded about showing it. After Dad died in the accident—Mom was there but, you know, she’s always so busy at the lab. Without Dad, I needed you. Mom honored his wishes by not inviting you to the funeral, but I knew that was wrong. That’s why I wrote.” She stopped with a telltale sniffle.

Martea pulled the necklace over her head and lifted her dark hair out from under it. She looked down at the necklace, ran her fingers up and down the variously sized beads. She felt like she’d lost her dad all those years ago when she’d left Jefferson. Now to lose him again, never having gotten to resolve that final argument between them—it was complicated. “I miss him too. I’ve been missing him for a while, I guess.”

“Why didn’t you ever write to me?” The sharpness of Lili’s words startled Martea, and she looked up to see her sister staring straight at her. It was a fierce look, a challenge.

Martea was baffled. “Dad wouldn’t have let me. You were still a kid! You didn’t have your own commlink.”

“But when I turned thirteen, I had one. And you never wrote to me. I tried to find you, searched the New Zion directory, but I didn’t know where you lived, and I didn’t realize that you’d gotten married and changed your name. It took me years to find you. But you could have found me. I was right there the whole time.”

Martea sat back, rebuked. She had been so busy building her new life, and wallowing in her anger at her father, that for long stretches of time she had forgotten that she even had a sister. “I—I’m sorry, Lili.”

That had to be followed by another hug. If the last one had been like a flood, this one felt like a fire coaxed back from the brink of going out. After a while, when they were both steady enough to face the kids, they headed back inside. Together.

“You know, you absolutely do not have to eat meat while you’re here,” Martea said, as she reheated the vegetarian part of the leftovers for Lili, “but you should know that the cattle are actually helping reclaim the desert. Back in the Before, they thought that reducing overgrazing would restore the land, so they restricted herd sizes and set up nature zones. But it didn’t work. Turns out, large herds of herbivores are meant to be part of this ecosystem. They trample the grasses, mulch the ground so it can retain water, and fertilize it. After they pass through, the vegetation grows back stronger than before. Since the cattle can eat the sagebrush and other native plants that require less water, meat is more practical in the desert.”

She dished up the pasta, put a plate in front of Lili at the table, and took the chair next to her. “It took me a while to get used to. I avoided it when I first got out here, but when Devin took me on our first date to eat burgers, I put on a brave face and tried it. I ended up retching in the bathroom. For hours. He had to drive me home, and I threw up all over his bike cart. Worst first date ever.”

“He still married you after that?” Lili laughed, with a twinkle in her eye.

“Yup,” Martea said. “What about you? Anyone special in your life?”

Lili began to explain her plans, about the boy she’d started dating at the end of secondary, how they were going to travel up north to study in the tech hub in Cascadia, how she was going to study engineering so she could take over Mom’s lab someday. When Lili finished eating, Martea took her plate over to the sink and began scrubbing it. When she turned to stack it in the drying rack, Lili was there with a hand towel. Martea smiled as she handed the dish over to her sister, an echo of the childhood chores they had once shared. As they finished the dishes together, Martea could feel something new growing, like a bulb long dormant in the desert ground receiving the first warmth of spring.

Liz Busby is a writer of speculative fiction, creative nonfiction, book reviews, and literary criticism; she is co-host of “Pop Culture on the Apricot Tree,” a podcast about pop culture from an LDS perspective.

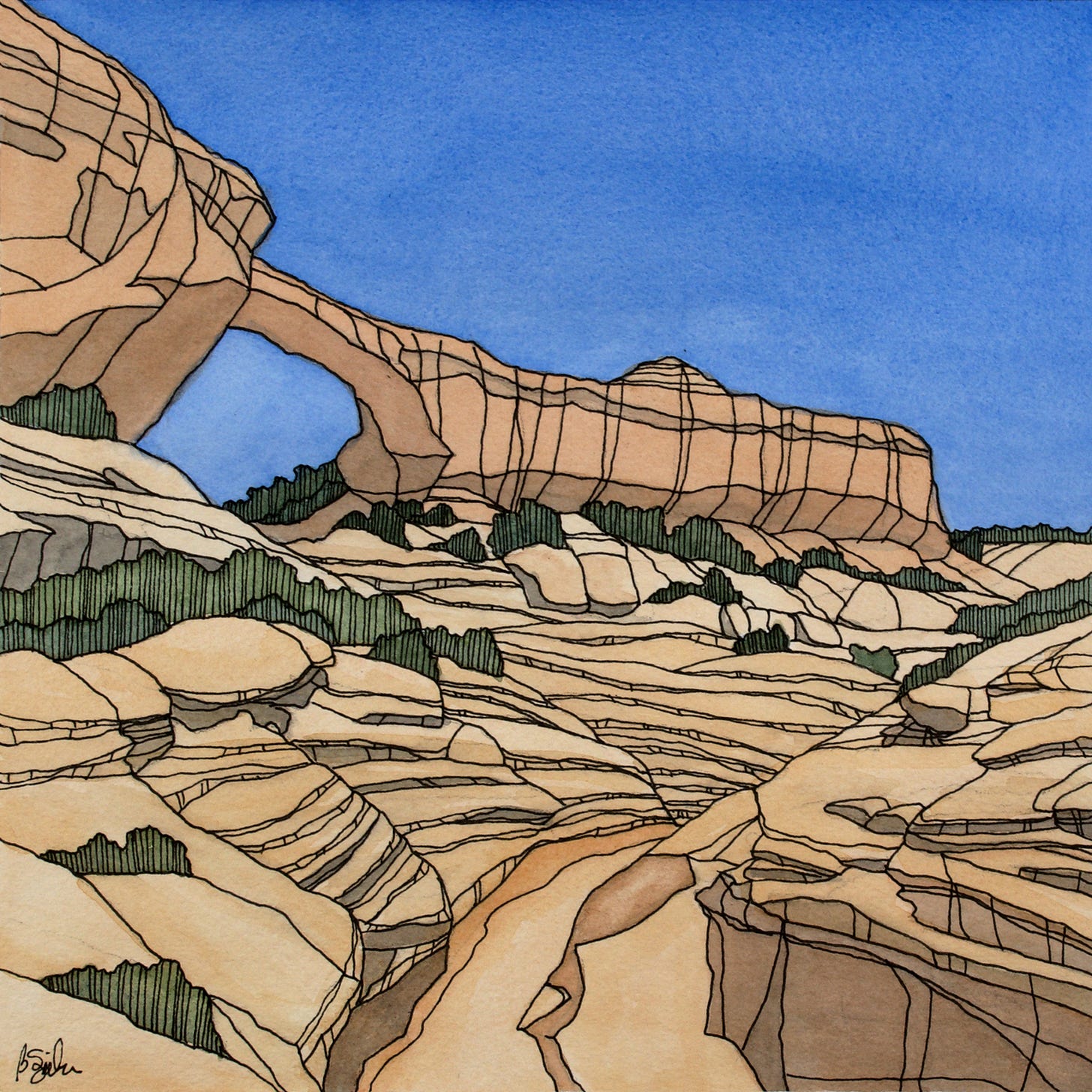

Art by Brekke Sjoblom