Recalibrating Unity

I was serving as a bishop in a North Texas ward when sacrament meetings worldwide were suspended due to the Covid-19 pandemic. We didn’t know it at the time, but it would be three months before we’d be cleared to worship in person again. In retrospect, that doesn’t seem very long. But like the beginning of an unfamiliar hike, without knowing the terrain, the landmarks, the ratio of inclines to rest stops, and even the approximate distance between trailhead and terminus, three months was a very long slog.

When we did begin gathering again in person, it was not flipping a switch from “pandemic” back to “normal.” We were given an attendance cap of fifty, and for the first time in our lives, members had to take the unusual step of RSVPing to sacrament meetings. Only one entrance and foyer were open, and every other pew was cordoned off for social distancing. Hymns were played by our organist, but we were instructed by our stake presidency and area authority not to sing them. We were limited to one speaker, so meetings tended to last only 20 minutes, after which a team of volunteers would spend an equal amount of time wiping down and disinfecting the pews, doorknobs, and light switches before the next ward arrived. There were no hugs, handshakes, and very few lingering conversations. We’d begun gathering, but there were still barriers that kept us from connecting. It wasn’t just on Sundays. We were all struggling to keep connected with our employment, our schools, and our communities. We were together. But we were also alone together.

Several months into meeting under these conditions, our ward council decided to conduct an online survey of the ward. President Nelson had recently said, “Good inspiration is based on good information,” and there were questions we wanted to ask. We wanted to know how ministering was going, how people were coping physically and mentally, and what unique and unexpected challenges we might help them with. I also had a hunch that this would give members a voice and help them feel heard and less isolated. Answering incognito, it would give people a chance to express unspoken concerns and hopes.

The survey asked a variety of questions. For example, on the typical scale of “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” we asked members to respond to statements like, “I feel safe attending sacrament meeting in person,” and “I feel the sacrament is safely blessed and administered.” We also asked members to respond to statements like, “I’m concerned about rising case numbers in our area.” Their responses were very helpful and seemed to give us a healthy snapshot of our ward.

But there was a section of the questionnaire where the answers truly astonished me. The survey concluded with open-ended space to respond to this invitation: “If you have concerns about attending in person that you would like to share, please let us know.” I’d imagined this final question would be mostly ignored. But almost everyone used the opportunity to voice a strong opinion. As our ward council reviewed these anonymous comments, I’m not sure any of us could guess which statements belonged to which ward members. These were stronger opinions than any that might have been shared in casual foyer greetings or even ministering visits. We knew our members, their professions, their children’s ages, and what callings they held. But these comments painted an unfamiliar picture for us. Knowing these are truly anonymous, here’s a small sample of the responses we received. I’ve deliberately ordered them to represent the pendulum of attitudes our ward council experienced as it swung wildly and with a wide arc.

I'm not coming back to sacrament until we have the virus completely under control and vaccines that are proven effective over the long term.

Start holding things live in-person. The idea that online anything could ever replace in person meetings is an absolute farce. Having live humans where you can read their facial expressions, feel the vibration in their voice, and know that when they look at you they see you and you are able to send body language signals and be seen and heard, is emotionally and spiritually essential. When someone looks at the "camera," they don't see me. They don't know me. They don't care about me. They can't ask me questions. It's almost worse than not having church at all.

The stake should go all virtual until the entire country is in the clear. Be responsible and health-conscious. Virtual sacrament meeting is awesome.

Do you feel the amount of social isolation we are enforcing on 100% of ward members is too much? Do you feel that low-risk members (those younger than 65, without major systemic disease) could return to completely normal church and activities and gatherings with no restrictions, and that high-risk members can self-isolate if they so desire?

People not wearing masks should not be permitted to enter the building and masks must remain on while in the building, no exceptions! Masks can be provided at the entrance. (My family and I have considered not attending in person for this reason alone. I am highly frustrated with this aspect.) Individuals should be limited from congregating outside, or at a minimum more forcefully encouraged to not group so closely together. As individuals exit and enter the building there should be greater control over social distancing. Temperatures should be taken—anybody with a fever should not be allowed to enter the building. One set of doors for entry, another set of doors for exit.

My toddlers are fussy, and NO ONE else brings their toddlers to church, so I'm in the spotlight as the lone disruptor. COVID does not affect children at all and they are not high risk at all.

It makes no sense to offer in-person church and virtual church. Should be all virtual. In my case, half of the family prefers to play it safe and stay home (not just for church, but for school and work, too). But the other half of the family attends in person. I'm paranoid that they will eventually bring home the virus. So having in-person church in some cases undermines the safety precautions some families are taking. Please: GO ALL VIRTUAL.

Even with the pandemic in our rearview mirror, the frustration and desperation in these voices are palpable to me. The realization we were a ward council of a congregation deeply and passionately divided on how we came together to worship Christ became an unexpected weight. It wasn’t just that our communal worship had been seismically disrupted. The reasons for and validity of the disruption was the very context for our need to adapt. One respondent opined the Church had capitulated to “the clown-rules of insane corrupt socialist agenda politicians,” which I have to extrapolate into their believing the virus was not a serious threat. Others shared the opinion of one who wrote, “I believe we should hold off until the vaccine is widely available,” indicating that they believed the virus was a significant enough threat as to stringently limit any contact. And others seemed to align with the concern that “members of our ward have demonstrated a lack of willingness to social distance, comply with wearing masks, or enforce those things during organized activities,” which acknowledges a threat with the ability to manage it through certain protocols. The more our ward council considered these diverse concerns, the more I came to believe it wasn't a polarity of opinions. It was a bog. The varying frustrations could have been plotted on an x-y axis. But each data point would have represented an individual or family desperately longing for a normal sacrament meeting, a lesson to teach, even the opportunity to help unload furniture from a new move-in’s U-Haul.

As it was, we were alone together, simmering in our differing opinions about why. We’d been approved to meet together in person, but more than any other time since the lockdown, the responses to our survey left me feeling even more isolated.

Serving as a bishop pre-pandemic was comparatively easy. I would interview members throughout the week to extend new callings, sign temple recommends, or speak to primary youth preparing for baptism. There were challenges that sometimes left me reeling, of course. But there was always a universal understanding and agreement about why we came together to worship on Sunday. But during the pandemic, that common agreement appeared to evaporate. One interview might conclude with someone telling me, “This pandemic nonsense will all go away after the election.” And that might be followed by another interview conducted via Zoom because the member was so concerned about their family’s health.

In Doctrine and Covenants 38:27, the Lord gives this instruction: “I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine.” In Moses 7:18, we’re reminded that “the Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind.” It’s one thing for members to agree on the tenets of faith, repentance, baptism, and enduring to the end. But when the very act of coming together for worship was laced with staunch, sometimes even combative attitudes about how and why we should or shouldn’t be there to begin with, being of one heart and one mind felt impossible.

Did Jesus face situations like this among His disciples? He must have, considering His ministry included such divergent backgrounds as publicans and sinners, Pharisees, Roman officers, and Zealots. Surely John the Baptist had different political opinions than the Roman centurion. We can’t assume that Nicodemus held no grudges against publicans and blasphemers. Matthew the tax collector must have seen the world through different eyes than Peter the fisherman. His disciples were hardly a homogeneous group. No wonder the Prince of Peace warned “whosoever shall say to his brother Raca, shall be in danger of the council: but whosoever shall say, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire” (Matthew 5:22).

We often over-simplify scriptural conflict to warring factions. Nephites vs. Lamanites. Early apostles vs the soldiers of Nero. Brother Joseph vs. an armed mob. But the scriptures are replete with examples of disharmony among close-knit groups and the challenge of facing it. Before the resolutions of the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15, Hebrew Christians were insisting that Gentile converts observe the Mosaic Law as part of their spiritual rebirth, even though they were all devoted to the same Christ. The king-men and freemen of Pahoran’s time shared a city and probably street corners, synagogues, and marketplaces, if not political ideology. And following the death of Ishmael, a good portion of Lehi’s party mourned, murmured, and “were desirous to return again to Jerusalem” (1 Nephi 16:36). I think their lamentations were another way of saying, “We just want things to be the way they used to be.” That’s what we were all saying in the midst of the pandemic.

One of the things the pandemic did for me was recalibrate my understanding of unity within a church setting. Before March 2020, I might have casually associated unity with increased meeting attendance, or seeing a well-attended ward social, or even people willingly accepting callings that challenged their schedules or comfort zones. But among the morass of divergent attitudes concerning our pandemic-era meeting protocols, the pandemic showed me how the truly unifying elements of our faith were untouched by the Covid-19 virus. At the same time, it opened my eyes to ways I had been blind to the most vulnerable among us.

I saw unity in the administration of the ordinance of the sacrament because while public meetings were postponed, the emblems of Christ’s body and blood continued to be sanctified in living rooms and at kitchen tables. But it became painfully apparent that not every home in our ward had a priesthood holder on hand in lockdown to administer that ordinance. Even with home ministers ready and willing to make weekly visits to single moms and widows, not everyone felt comfortable doing this in our socially distanced world—especially those who saw themselves as high-risk. While I was rejoicing that we could take the sacrament at home, my stomach was in knots about many who couldn’t. And even as the bishop of our ward, I didn’t have any answers for them.

Similarly, I saw unity in our efforts to watch over, be with, and strengthen each other in new ways through texts, phone calls, and virtual meetings. Relieved of the crutch of exchanging casual pleasantries in the corridors of our meeting house, I saw many ward members connect in profound and uplifting ways. But the frustrations many shared in their responses to our survey made it clear that not everyone was thriving—even those who came regularly once sacrament meetings were allowed to continue. Just showing up and smiling was no longer reason to presume spiritual and mental health.

Pre-pandemic, I thought I understood unity. But with the challenges the pandemic posed and exposed, unity feels like a primordial soup of emotions, needs, and responsibilities. Creating unity among the Saints is an ongoing, active process that goes much deeper than resolving spats and mollifying hurt feelings. It’s continually, even relentlessly, asking the question, “How can we connect with people in ways that are most meaningful to them?”

Just over four years have passed since that initial lockdown. And though we’re back to “normal” as a church, the pandemic exposed ways that we might never be unified—political allegiances, cultural beliefs, and even acceptance of administrative policies to name a few. But it’s clear to me now there’s no rich tapestry to be woven from those brittle threads. As I’ve considered which qualities and characteristics I saw most strained during the pandemic, patience, tolerance, understanding, and curiosity are at the top of my list. I saw them wane in our ward and in my own life. The paucity of these Christlike attributes during that time testifies to me that they must be building blocks of true unity. Why else would we find them in such short supply when feeling so alone together? And now that Sunday gathering is de rigueur, gathering and singing and hugging and laughing without impediment, it’s even more important that we remember the inconveniences we experienced. Why would we deny ourselves the relentless pursuit and diligent practice of these godly characteristics today?

Greg Christensen is a writer and creative director who's called Salt Lake City, New York City, Budapest, Chicago, and Geneva, Switzerland "home." He is currently living in Dallas.

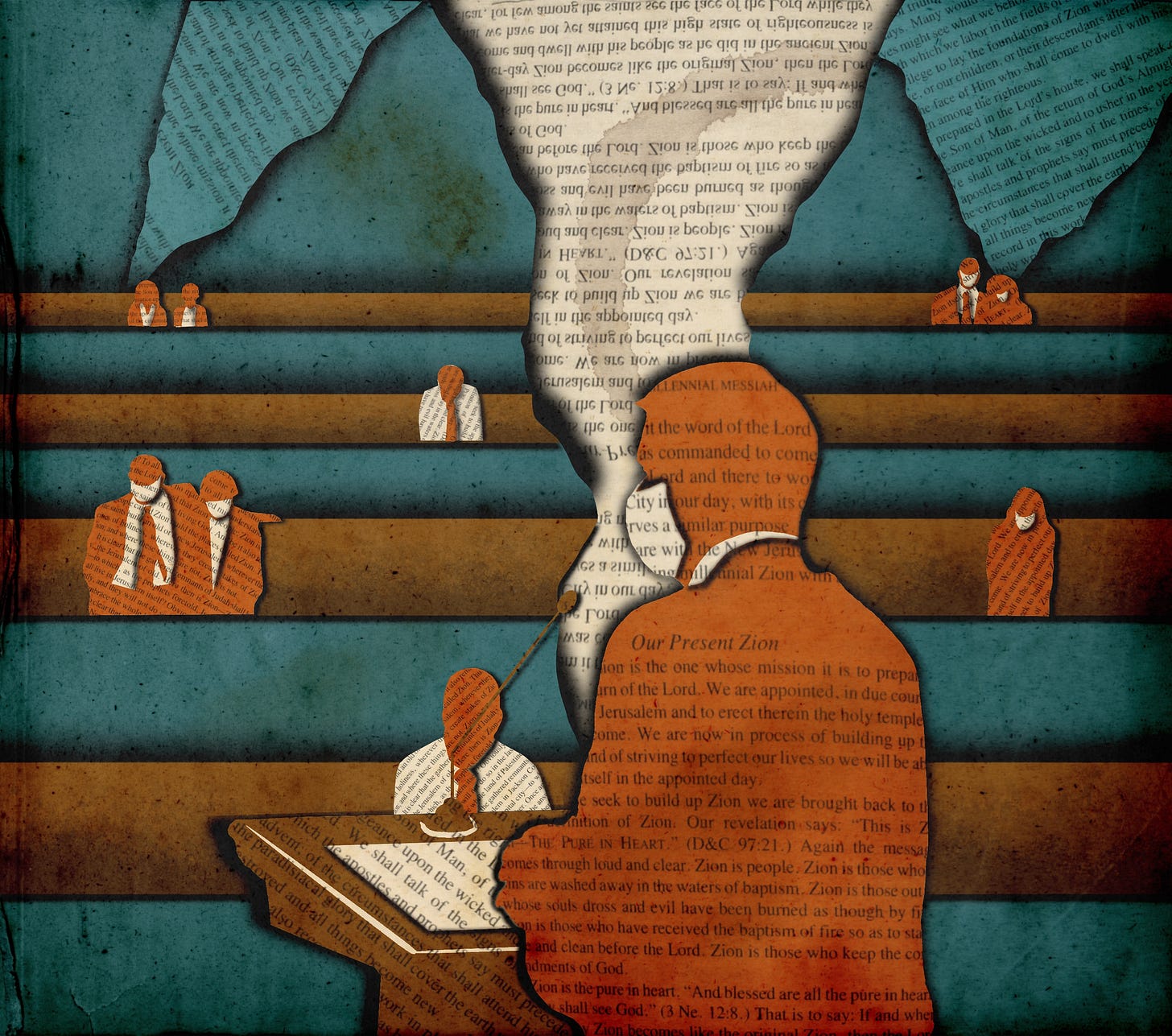

Art by Charlotte Condie.