The vision does not terrify but soothe…here is rest indeed. The God of peace makes all things peaceful;…We see him as a king who after hearing causes in his court all day long, has dismissed his crowds of attendants, ended the labour of the day, and retired to his palace at nightfall. He entered his chamber with the few friends who share the intimacy of that retreat. …his serenity mounts as he looks calmly round upon the faces of his dearest companions. … So (in this inner chamber of contemplation) God deigns to show himself lovable, serene and peaceful, sweet and gentle, full of mercy towards all who look on him.” —Bernard of Clairvaux (352-53)

Kenneth Kirk was an Anglican theologian and bishop of Oxford in the mid-twentieth century. He wrote a magnificent history of Christianity based on one central theme: the tension between the necessity for an organized framework to promulgate and administer gospel; and the tendency of any formalized religion to redirect attention from God to the self: “If my aim in life is to attain a specified standard, or to live according to a defined code, I am bound continually to be considering myself, and measuring the distance between my actual attainment and the ideal. It is impossible by such a road to attain the self-forgetfulness which we believe to be the essence of sanctity.”

The only path forward, which he charts as the quest for the vision of God, is the path of worship. By worship Kirk means the disciplined practice of self-forgetting—a practice best exercised and honed in prayer.

One challenge in this quest is that prayer can aggravate, rather than alleviate, the preoccupation with self. And this is because we often find in prayer a catch-22. We want to be drawn to prayer by love rather than selfish need, we want to be filled with the desire to simply rejoice, commune, adore. But unless we have had an experience of God, we find ourselves supplicants rather than worshippers. Who would not covet the vision of God described by Bernard of Clairvaux? It seems highly unlikely that the many souls who wander, who “walk no more with him,” ever had such a fulsome experience of God. Most of us are a long way from such theophanies. And until we have known and felt a divine embrace of some sort, we are occupying the role of anxious petitioner, waiting to see if anybody is even home. As Kirk wisely recognizes, “To expect a response of one particular kind is to doubt the resources of God; to expect a response of an emotional kind is once again to be looking at oneself and not at God. And neither one of these attitudes has any place in Christian prayer.”

But if such expectations have no place in prayer, and we are searching for, rather than responding to, a divine voice, how do we take the first steps on the path to such communion? Kirk has useful counsel in this regard. Approaching God in prayer can assume the nature of worship—even in the absence of an experience of God’s voice—if we operate on the principle that worship is manifest in our readiness to love. Worship can begin when it “rises in a heart which at least desires the well-being of God’s whole creation, and issues in the resolution to promote that well-being when and as opportunity allows.” Prayer as an expressed disposition to be co-participants with God in his healing work is the highest form of worship he desires. The beautiful consequence of this kind of prayer is that it sets up the ideal conditions for us to hear God’s response, a litmus test by which we can identify that voice: “unless an alleged experience of God brings with it a call to disinterested action of some kind or another—unless there is reaction, response, reciprocity—we shall scarcely be able to avoid the conclusion that something is amiss.

There is another kind of prayer that is also a form of worship, and that is the prayer of surrender. This variety was expressed by George MacDonald.

If I find that I can neither rule the world in which I live, nor my own thoughts or desires; that I cannot quiet my passions, order my likings, determine my ends . . . ; that I am no king over myself; that I cannot supply my own needs, do not even always know which of my seeming needs are to be supplied, and which treated as imposters; if, in a word, my own very being is in every way too much for me; if I can neither understand it, nor be satisfied with it, nor better it—may it not well give me pause—the pause that ends in prayer?

To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

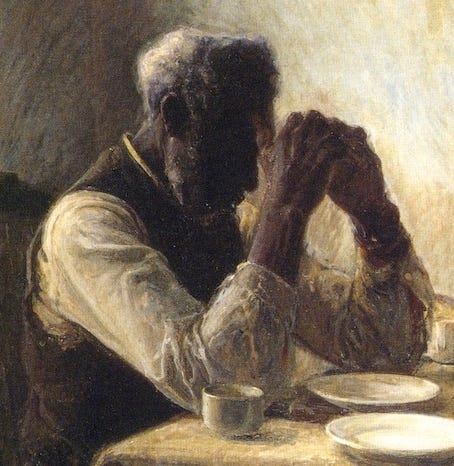

Artwork by Henry Ossawa Tanner

A thought induced by the Kenneth Kirk quote:

When Jesus invites us to come to Him, he is more interested in direction than distance. To avoid self-focus, we should move in the direction of Jesus rather than constantly comparing ourselves with Him.

This is bringing to mind an essay by an Anglican priest —Tish Harrison Warren— titled “How to Pray With Our Eyes Open”. Thank you Brother Givens for another wonderful treasure.