Frank Herbert’s Dune is a work of literary art. Readers of the books or viewers of the recent movies are struck by Herbert’s expert world-building that makes the reader or viewer teeter between sensations of exotic strangeness and profound familiarity. One moment we find ourselves flying through space faster than light, the next the characters are dueling with swords for the right to marry a princess and rule an empire. Herbert’s real genius is his layering of the thematic elements; Dune is not just about western imperialism, exploitation of natural resources, technology, individual free will, utopianism, romance, nuclear proliferation, or family legacy but a clever tangle of all this and more—indeed, almost everything it means to be human in the modern age. How does Herbert tie it all together? Religion, and religion’s very real, nonfictional interface with community and identity.

So what genre should we categorize Dune in? It’s clearly not historical fiction, as the invented characters operate in no historical time or place. It might be tempting to consider Dune an obvious science fictional world because of the laser guns and interstellar travel but the plot does not revolve around any new scientific or technological advancement. There is a love story, but it’s not exactly a romance either. Maybe fantasy brings us a step closer to properly framing how it features mystical powers and forces. To my reading of the books and viewing of the films, the most potent theme throughout the story is religion. Especially as a person of faith, why not read Dune as a form of religious fiction where imaginative religious complexities create an engaging story?

Beneath the overtly religious imagery—the scheming women wearing long black robes chanting in Latin, fanatic warriors receiving a blood ceremony serenaded by a chanting monk, or desert nomads recording prophecies in Arabic for example—Herbert drives the plot around richly interwoven religious, scientific, and social concerns. For example, contemporary fears about artificial intelligence have been animating our world since before 1956, when the term was coined in English. Published in 1965, Dune is set in a far distant intergalactic society formed from the ashes of a terrible war with artificial intelligence, a “jihad” due to the fervor of those who struggled against machine domination. Curiously, Dune is full of advanced technology, but none of it resembles a computer or a robot; instead, underlying the scientific advancements of Dune rests a religious injunction worthy of contemporary debates about artificial intelligence (and its anthropomorphisms): "Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind." Herbert continues a tradition dating back to at least Genesis in naming a transgression any attempt of a creature to surpass their creator.

The future in Dune is advanced not by the virtues of force fields or spaceships but by its stunning range of different communities of people with unique gifts: Herbert’s characters include people who can precisely collate massive amounts of data and calculate sums better than supercomputers; people who can invoke superhuman speed and reflexes beyond an Olympic athlete; people who can control pain and endure extreme discomfort and deprivation; people who can control the minds of others; and even people who can lead others with magnanimity and a presence rarely seen in our world. Not unlike how secularists may turn to technology and science to drive human progress, Herbert and we who believe in a God who is a Father of our spirits seek enlightenment by releasing what we hold within.

Dune features the unscrupulous who manipulate cultures to their own gain, worship power and profit, seek cunning brutishness, and would trade earned loyalty for exploitative dependency. As Kara Kennady argued here, aside from these less creative concerns with organized religion, Herbert has a much more subtle point to make. His point appears to be focused on the transformative potential of faith to help us recognize higher truths about the human condition. Religion in the world of Dune exists not to script the moral lives of individuals but to enable characters to transcend their limitations and circumstances. Herbert in his appendix explains:

“True religion must teach that life is filled with joys pleasing to the eye of God, that knowledge without action is empty. All men must see that the teaching of religion by rules and rote is largely a hoax. The proper teaching is recognized with ease. You can know it without fail because it awakens within you that sensation which tells you this is something you’ve always known.”

There’s almost no explicit theological reading or language in Dune. Rather its core religious meaning emerges as its various characters acquire powers and transcend limits by turning to their beliefs and senses of communal belonging and identity, and by passing through various defining gauntlets and history-altering trials. “The mind can go either direction under stress,” Lady Jessica claims, “toward positive or toward negative: on or off. Think of it as a spectrum whose extremes are unconsciousness at the negative end and hyperconsciousness at the positive end. The way the mind will lean under stress is strongly influenced by training.” In his own coming-of-age tale, young Paul must not merely survive terrible privations through his own power of self-control but also grow by living according to principles that connect and animate his constitutive communities and identity. In this Gestalt sense of being greater than an individual, Dune stands out as an allegory for how our own cultures, communities, belonging, and trials enable a communitarian transhumanist transformation.

Paul will make many transformations through the story and become a liberator and justice seeker who wields ultimate political, social, and theological power. He even raises himself from the dead, recruits an army of desert guerrillas, and learns to be at one with nature. It’s as if Herbert took the archetypical messiah from every world religion and shaped Paul into his religio-ubermensch.

This theme of an action-oriented religion as a means for reclaiming a higher order recognition about oneself and one’s community is captured succinctly in even the trailer to the second movie, where Fremen Leader Stilgar confesses, despite Paul’s protestations against those who would pedestal him as their leader, “I don’t care what you believe, I believe!” It is the faith of Stilgar that reveals an eventual truth about Paul that Paul could not recognize until after the trial of action, effort, and his own faith: Paul becomes their leader. Stilgar is right to believe, and Paul needed Stilgar’s belief to fulfill his destiny. Dune highlights how our covenant community is a fundamental ingredient in becoming more than we are as we encounter trials.

Herbert’s depiction of how this inner potential is released has pertinent insight into our spiritual journeys, especially as we live within covenants. This galaxy of people constitutes Dune’s distinctively quasi-religious message: people—or rather, from our vantage in the present, what people may yet become—are what make the future sacred. None of Dune’s people receive their powers from outside forces—no radioactive spider bites, no particle-accelerator accidents, no dei ex machina. Even the powers of the mysterious spice only function to release inherent human potential. This is his point: the key to unlocking that inner potential comes from relationality within religious groups. The fantastical world that is Dune comes from people unlocking their powers within communities and families, then driving towards spiritual goals. In this lies its core religious reading for me.

In a modern world that consistently finds new ways to celebrate creative ways to express individualism without acknowledging the need for connection, Herbert offers a profound counterargument resonant with covenant peoples: that spirituality and all of its struggles, paradoxes, enlightenment, and even transcendence happens through networks of relationships. As the fictional Paul and the real me have both discovered, these relationships and our place in them are often too complex to discern on our own, but they also form the fundamental building blocks of our identity. However, a communitarian system of belief designed to enhance and empower the individual will ask that individual to turn to others in meaningful bonds of responsibility, love, and even covenant as the means of growing through trial. It is through others that we, like Paul, find spiritual satisfaction and destined becoming.

How again should religious readers read fiction like Dune? We read good science fiction and fantasy for its fresh merger of spirituality and fiction; we read for the weave of character arcs who must make sense of themselves in a universe defined by powers and purposes greater than their own survival; we read tuned to the spiritual struggles of the characters, in hope that, by discerning resonant truth in their actions, we might also understand our own. Of course, this same resonance also requires an appropriate distance, or a critical posture that welcomes helpful meaning while also declining to mistake literary truths for the whole of spiritual truth. If we are to believe, as I do, in principles as fabulous as the Plan of Salvation and a Savior, then what can we learn from reading, at a certain distance, in the reality of worlds as remarkable as Middle Earth, Hogwarts, or Dune? In other words, as we learn to read our own world and its higher orders of real spiritual, scientific, and desert-swept meaning, can we not learn to rewrite our own life narratives to be a bit better lit by the imagination, communities, and lessons of protagonists that have gone not just before us but also beyond us in science fiction or fantasy?

After all, when describing the rich spirituality that flows from the restored gospel and its associated covenants, what better word could we choose than fantastic?

Spencer Yamada is an Entrepreneur and PhD candidate in Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University.

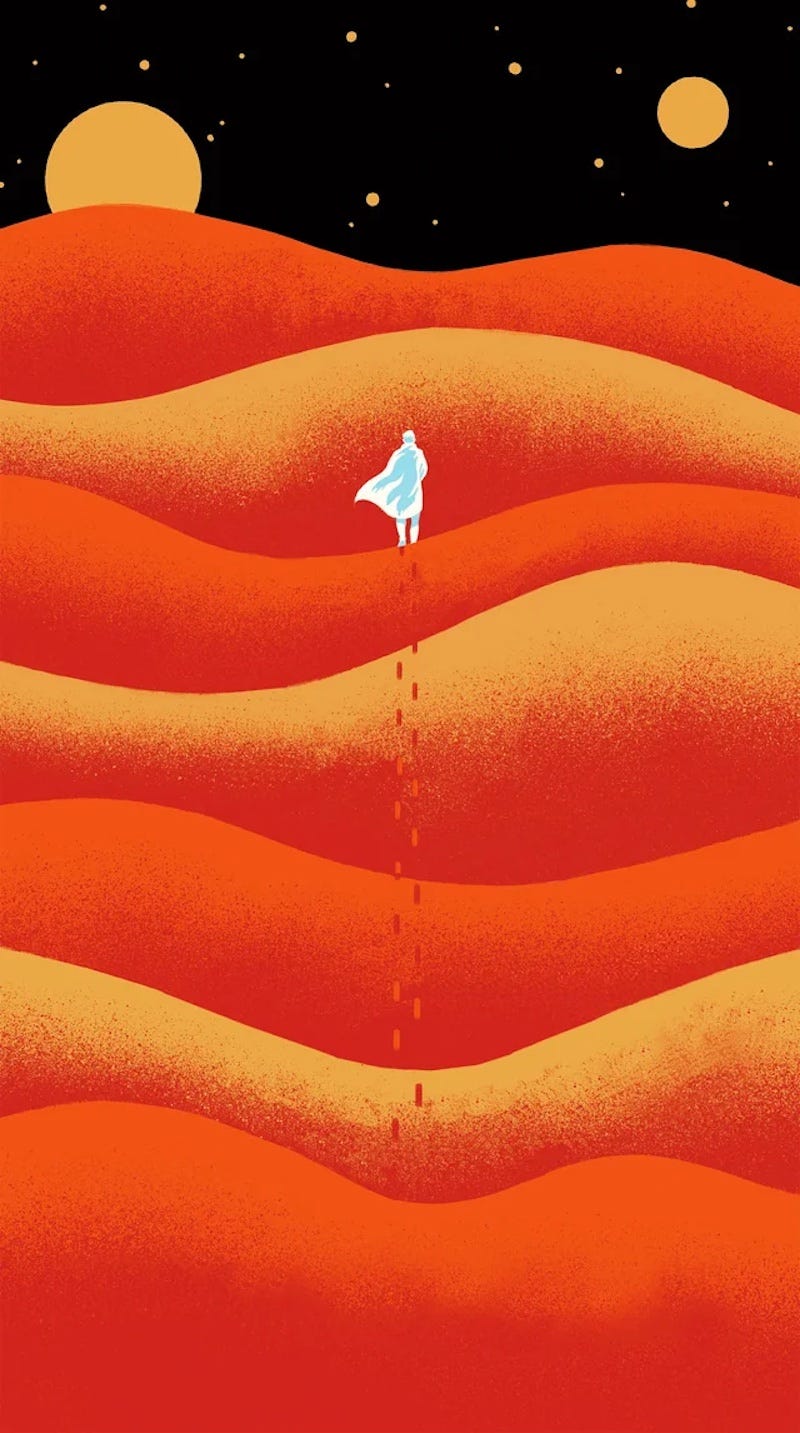

Art by Jim Tierney.