Positive Peace

Ordinary People Planting Seeds of Goodwill

As an American expat raising young children in England, I work to bridge conflicts between the head teacher and our parents’ association, the board of directors and residents in my building, my five and seven year old, my Palestinian and Jewish friends, my politically warring siblings and parents, and progressive friends and religious institutionalism. Clickbait articles with headlines on irreparable generational gaps, fragmented families heading into the November presidential election, and the relative rectitude of student protests cause me to question the possibility of individual, familial, or societal peace. Trendy answers to these problems feel more like avoidance and resignation, often leading to the conclusion that we no longer even agree on enough facts to have coherent discussions. It might be packaged in shiny new wrapping by pundits and commentators, but how new is this disease of division?

Of all the things he could have devoted his life to, Jesus Christ chose to offer a roadmap through our perplexing questions about peace on his altar of instruction. The Savior’s brand of peace, positive peace, offers more than the negative peace of neutrality and coexistence. He suggests a form of love, of positive peace, that cultivates sustainable social justice and builds resilient security for every one of his brothers and sisters. Stemming from his atonement, positive peace advocates for reconciliation and the "integration of human society" (Johan Galtung, 1996). It doesn’t just prevent violence, it builds and sustains connection. Christ’s architecture for elevating humankind encourages a higher ideal of love, not just love that mimics or performs for rewards, but one that builds spaces where everyone belongs, feels secure, and desires happiness for others.

As the author of peace, Christ broke down the barrier between Jew and Gentile, God and Man. He asks us in kind to find more safety in community than in riches, to love others without making them like ourselves, and to embrace our enemies with familial warmth. A beautiful irony is that His peacebuilding is the art of tearing down walls. Peace theory provides wise suggestions for incorporating Christ’s new testament morality.

An important first step in positive peacemaking is to train our hearts to peacefully relate to others. Our behavior and priorities will align as a result. Peace discussions sometimes feel too vaguely optimistic or expansive for the routine lives we comfortably inhabit. Instead of attempting to eradicate violence or condemning anyone from a moral standpoint, we can begin by asking ourselves, “what is preventing me from choosing peace?”

Positive peace sheds assumption-driven conclusion-making.

As I accept Christ’s invitation toward a more interrogative faith, I am deconstructing the antagonistic habits I’ve inherited, replacing my divisive thoughts, and questioning harmful religious traditions I’ve excused in the past. My current process includes confronting my assumptions and judgments about temple eligibility based on who I notice is wearing temple garments and who isn’t. For that matter, I stopped assigning religious meaning to white shirt wearing during Sunday worship. I depatterned my hyper-recognition of who passed the bread and water during the sacrament. I unlearned my superiority for using traditional “thee” and “thou” language rather than informal references to God. In the commandment to love our neighbors as ourselves, there is a very important mention of self. Christ asks us to build up our neighbors’ sense of self not by making them like us, or mirroring our love for ourselves, but by supporting who they already are. Diverse human experiences are the “workmanship” of God’s hands (Moses 7:32). God weeps at our enmity not because we are different from one another, but because we have the potential to bridge the gap between unity and enmity and often choose not to. Despite our differences, we have equal or more important things in common in Christ.

Positive peace leads to constructive resolution of conflict.

Most primary schools in England hire a playground coordinator to monitor the children and prevent unfairness, bullying, and harm. Schools striving for social and emotional student health understand that children in their early years, who live in the moment, carry less fear, are very good at forgiving, and are naturally receptive to building community and peacemaking habits. Peace-profiling the young is particularly wise because it furthers the goal of building long-term, consistent systems of peace. This year, my daughter’s primary school introduced a “goose and gosling” program that encourages students to talk and understand the viewpoints of others. Each child in the oldest year, year six, is paired with a four- or five-year-old in the entering class. This provides them a safe person to turn to, a familiar face, and a pipeline for confidence in their new setting. Where a division between “infants” and “upper years” used to dominate their educational space, I now hear my young one looking for and calling to her “goose” in genuine friendship. More than once, she has turned to this experienced, cool-headed advocate to help her solve simple playground disagreements. In its fledgling year, we’ve already seen the positive change programs of integration like this can bring.

Positive peace replaces insularity with inclusivity.

There’s a woman I admire in my congregation. We first collaborated on humanitarian work during the evacuation of Afghanistan in 2020, and I now support her in running a clothing bank in Central London which primarily serves asylum-seeking refugees. Through listening to deeply painful first-hand accounts, she has refined her ability to mourn with these victims of violence and, both figuratively and literally, clean, collect, and walk in their shoes. I see the empathy she practices expanding into other facets of her life.

On a particularly frustrating Sunday in Relief Society, I did something I’ve gotten better at not doing, and engaged with a strong-minded orthodoxy-focused sister on the issue of homosexuality and inclusion. I usually expect my friend to send me a conciliatory text of agreement and shared frustration, but having received none I sidled up to her after the meeting and fished for validation. After listening to me for a minute my friend asked, “ I wonder how Sister Bell is feeling after that meeting.” Her assertive honesty knocked me to the side for a few days. It wasn’t unkind. It was an uncomfortable, humbling response from a friend that invited me to recommit to integrity and peace through Christ. Peacemaking in that instance meant prioritizing tolerance for community members with different viewpoints over my desires for social validation, and recognition that ideological positions could be addressed in a more constructive and loving way. Latter-day Saint culture can sometimes feed insularity and tribalism, but it also has the potential to be an incredible resource for peacemaking. Latter-day Saints are active community builders who learn communication and collaboration early on. Refining and harnessing these positive aspects of our culture, like our organized communication and ability to rely on one another, can empower us as Christ’s disciples of peace.

Positive peace requires ordinary people.

Ordinary people, meaning people like my friend with a range of friends and acquaintances at church, school, and work, are uniquely positioned for building peace frameworks through the connective tissue of community. In volunteering with young mothers, I’ve been surprised what a vital peacemaking resource my friends are because they are trusted by community leaders and authorities, like the school headmistress and directors of local government councils, while also creating and coordinating grassroots channels such as online chats, parent associations and social groups. So much good informal community work happens in these cohesive, active units, and primarily among women. Convincing average citizens of their important role in peacemaking is called “building a peace constituency” (Lederach, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies).

Christ calls us to this constituency. While leaders and administrators are often constrained by administrative red-tape, and more vulnerable members of society are preoccupied with daily survival, ordinary people have the precious gift of flexibility. Citizen-based peacemaking, such as the kind that happens between members of a congregation, and between congregations and communities, is “instrumental and integral, not peripheral, to sustaining change” (Lederach). Citizens, normal people, members of the church, are the church, are the schools and are the government. After leaders serve their terms and leave their jobs, ordinary people remain invested and crucially central to the daily struggle for positive peace.

Positive peace heals damage caused by miscommunication and hurt feelings.

The block of buildings where I live hides a central garden. For decades, a committee of gardeners have meticulously planned and manicured it for the enjoyment of all who live there. At first I struggled to grasp the dynamics and occasional conflicts of the fast-moving playful children, their protective parents, and these legendary women defending their hard-earned botanical investment. Interested in learning the English way of gardening, I made a special effort to listen at the garden committee meetings, teach my young children respect, and prevent any unhappy encounters. Caught in the flow of gardening, I’d be learning how to properly prune my roses one moment and then having hushed conversations with moms too afraid to toss a dirty diaper in the garden bin for fear of reproach by the older gardeners.

One day, my sometimes wild four-year-old, who was feeling proud of casting her play fishing rod, walked up to a group of aged matriarchs with their canes, secretary skirts, orthotics and nude tights, and sent her dummy bait flying down the lawn. Completely outflanked, she took a tongue lashing for the “impropriety of it all” before I could reach her. Too young and alone to muster a reply, she retreated inside, buried her head under her pillow and cried tears of confused shame. In the moments that followed, I recognized a crucial opportunity to break the longstanding habit of negative backbiting and set a better pattern for our dialogue as a community. Fighting my natural reaction to shrink inside and hold my broken child, I held their gaze calmly and talked about how my daughter reveres them, how her excitement will eventually mature into impulse control, and how I would prefer if they would bring their criticism to me as her trusted adult. My momentary choice began to repair damage that existed before I even arrived. Since our encounter, the “garden ladies” have opened their hearts to us. They’ve confided they were also hurting from the decades-long division between the younger families in the community and themselves and requested our help healing it. I’ve noticed them wielding more patience than before. We learned that they are fiercely bonded through widowhood, neurodegenerative illness, and other hardships that come with aging in a busy city. Much good has come from participating in their support system. Every lengthy overly-formal phone call of theirs is a welcome treat. I now regularly find peace offering magazines, floral cuttings, and tools on my patio table and soft “hello” knocks on the glass door. My last voicemail from one of them, about borrowing baking tins, ended with “thanks for listening.”

Positive peace means marginalized groups have their say.

In a society that rewards efficiency and material success, patience, listening, and self-restraint are not often values that speak to the bottom line. It is faster and easier to achieve a result through coercion, commandeering, and control. But, to follow Christ’s pattern, peace must tempt us more than power. As an American living in England, it’s been astounding to watch the police interact with rough sleepers and addicts. One evening, I watched from my balcony as a team of police invested more than two hours to walk with, talk with, and eventually gently convince a manic man to climb in an ambulance for medical attention. On several other occasions, I’ve watched the police sit on the sidewalk in conversation with the troubled and downcast, listening, offering advice and rarely, if ever, becoming verbally aggressive or physical. It’s moving to see someone in a position of power willingly take a more susceptible physical position.

There seems to be an important component of peace that requires face-to-face connection. It’s equally motivating to see police de-escalate a situation—not just to clean the street or shield the community from disruptions but for the more compassionate purpose of meeting their particular needs and assessing their pain without force. As someone from a native country with an awful reputation for police brutality among its peer nations, sometimes it seemed to me in the past like it might be easiest to defund or disavow such institutions altogether. However, I’m seeing in practice that for positive change to last, everyone impacted by society’s struggles with violence and inequality needs to be included in the process of building peace, including perpetrators, law enforcers, and those who are most marginalized in society.

Positive peace in its most complete form does require larger-scale reform within institutions and brokering macro political solutions. This may be a notion so intimidating that it alienates normal people from action. But, drawing from Christ’s example, we understand that incremental, individual change in our ordinary lives, through patient conversation, practiced tolerance, self examination, and genuine compassion, is a vital beginning to Christ’s expansive peacemaking among people. Like the mustard seed, the least of seeds, we as individuals and local communities can become great trees of goodwill, such that many birds will feel comfortable perching and nesting together in our welcome branches (Luke 13:19).

Candace Queathem grew up in the rivers and mountains of Idaho. She studied at Brigham Young University before earning her law license in California. After completing post-graduate legal studies, Candace moved to London with her family. Candace volunteers as the community outreach specialist for the Hyde Park Stake.

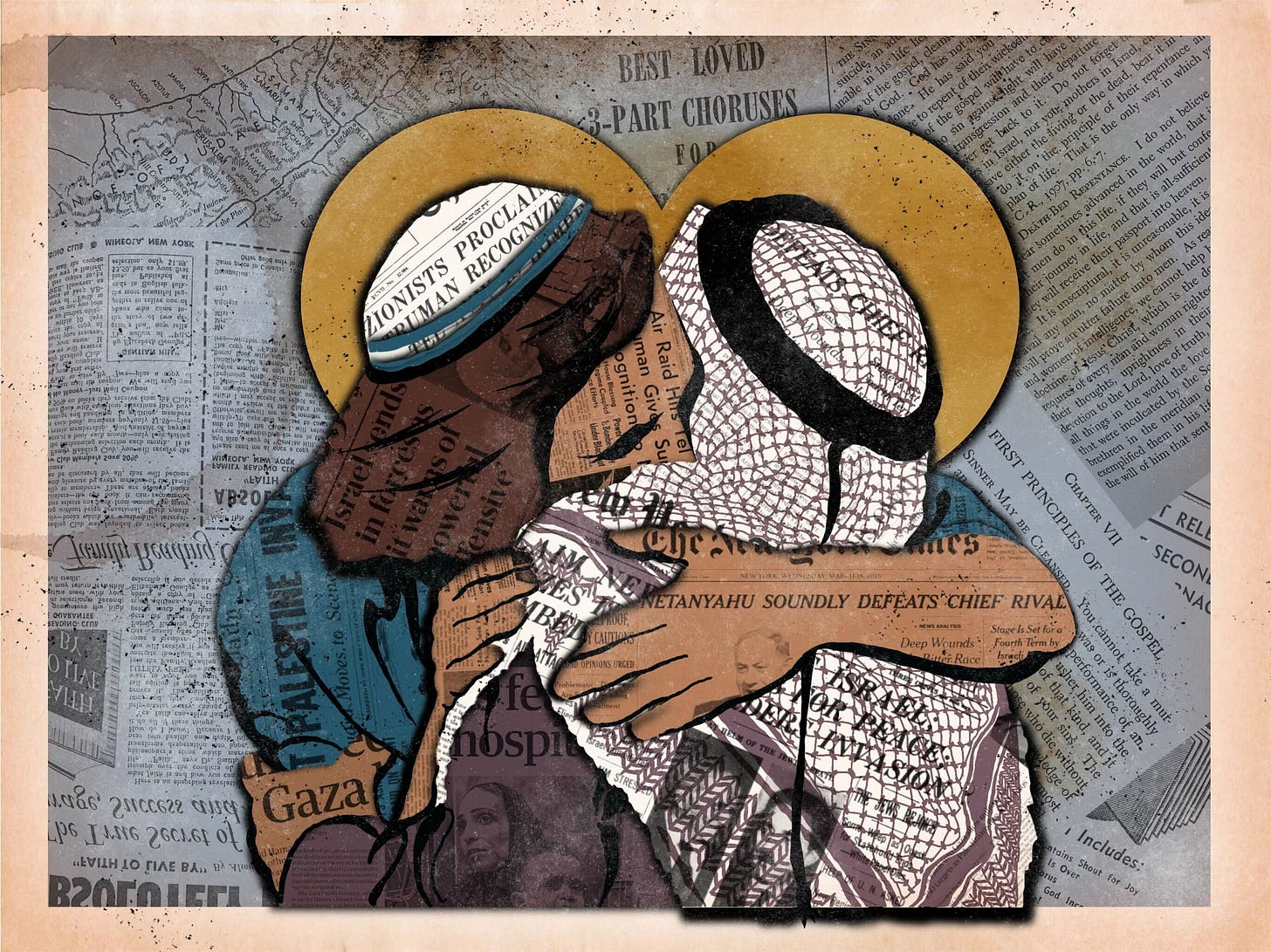

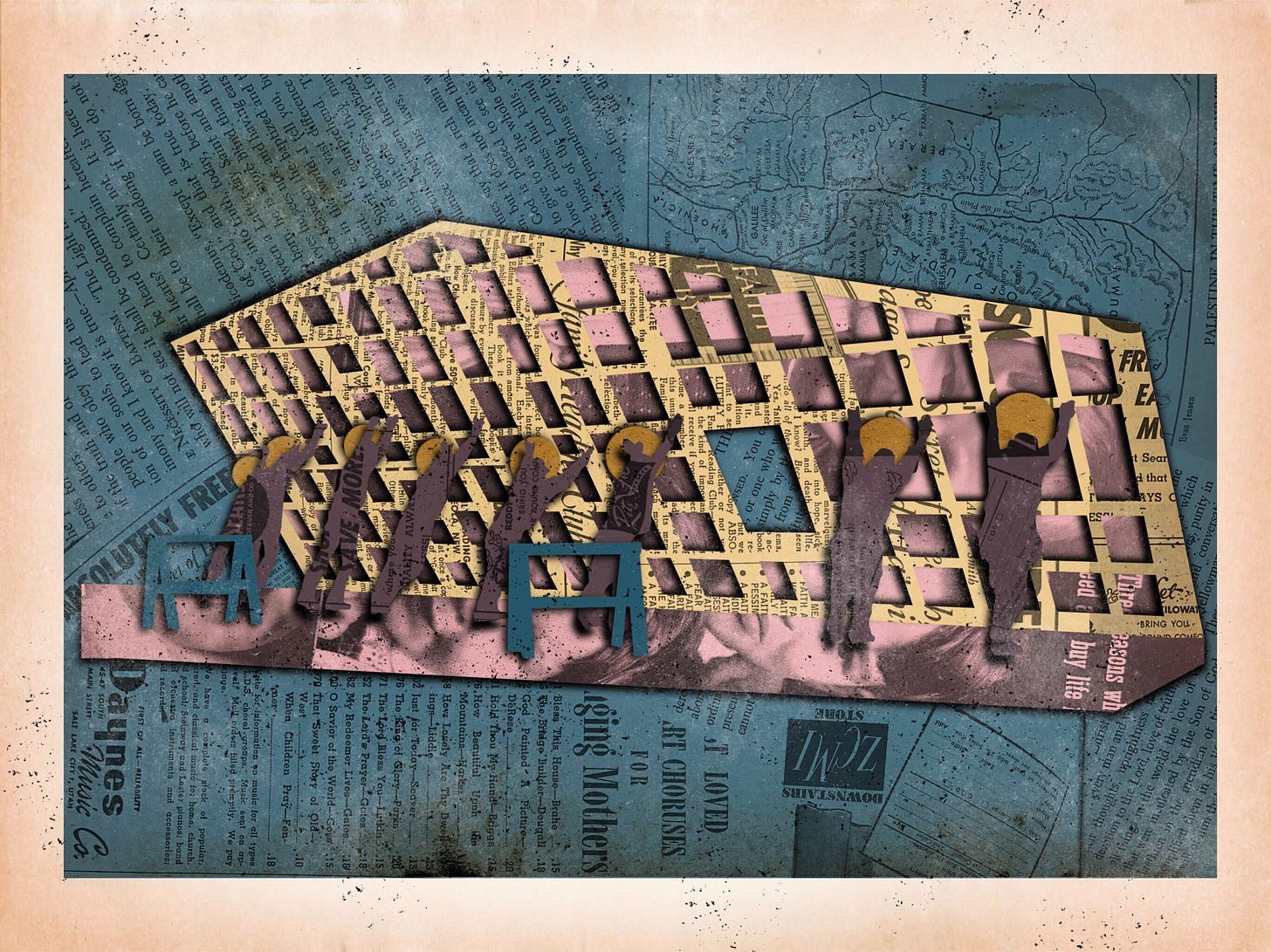

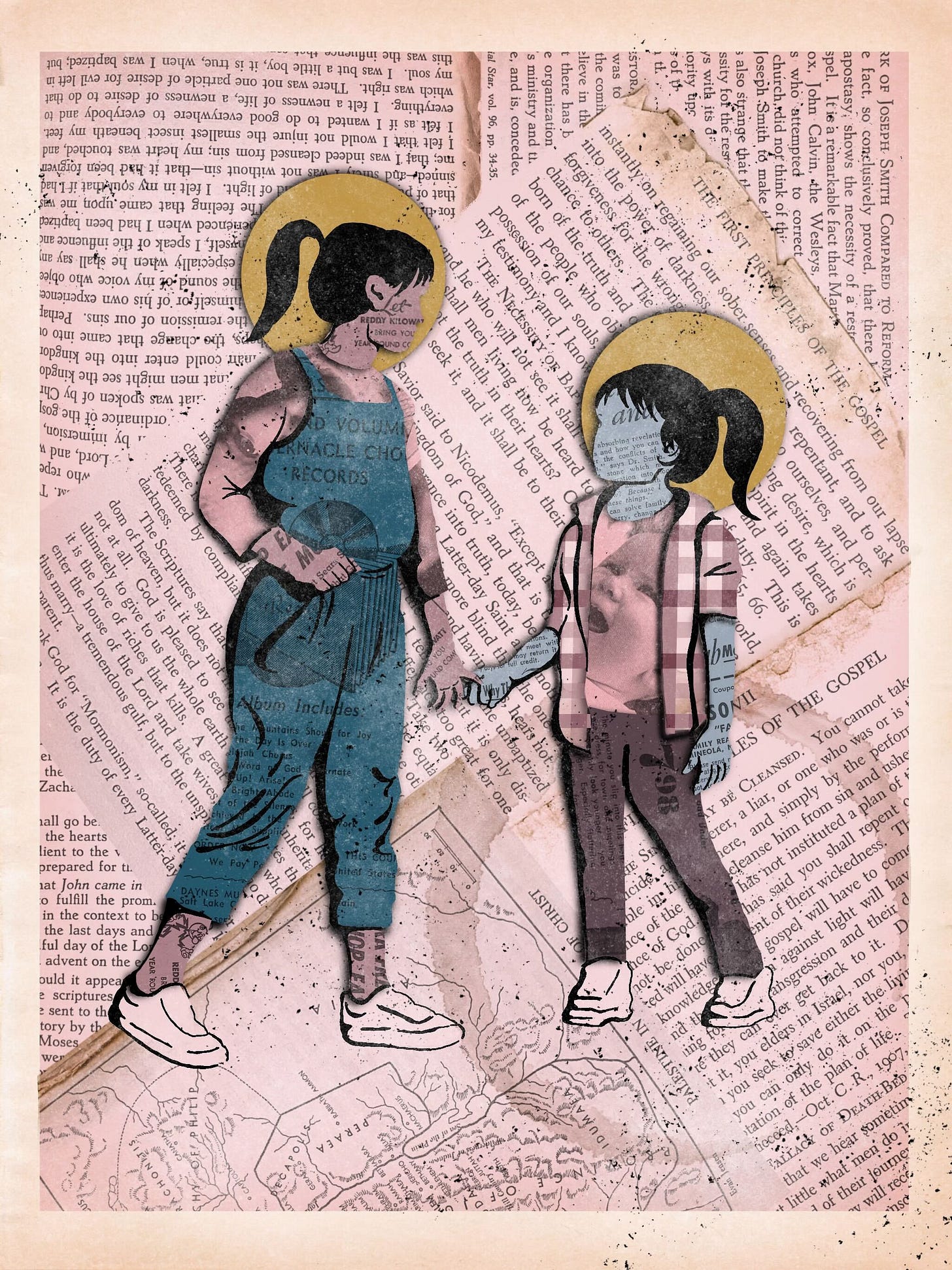

Art by Charlotte Condie.

I love this article, particularly the story of the garden ladies. My neighbour is consistently critical of the noise my grandchildren make in the garden. His sniping comments about bad parenting continue despite the fact that I have told him they have ADHD and autism (they can be a bit screamy). I know I need to find a better way to defuse the tension but I have been avoiding it. I need to follow your example. Thank you.