Pioneering Day

Celebrating Courageous First Steps

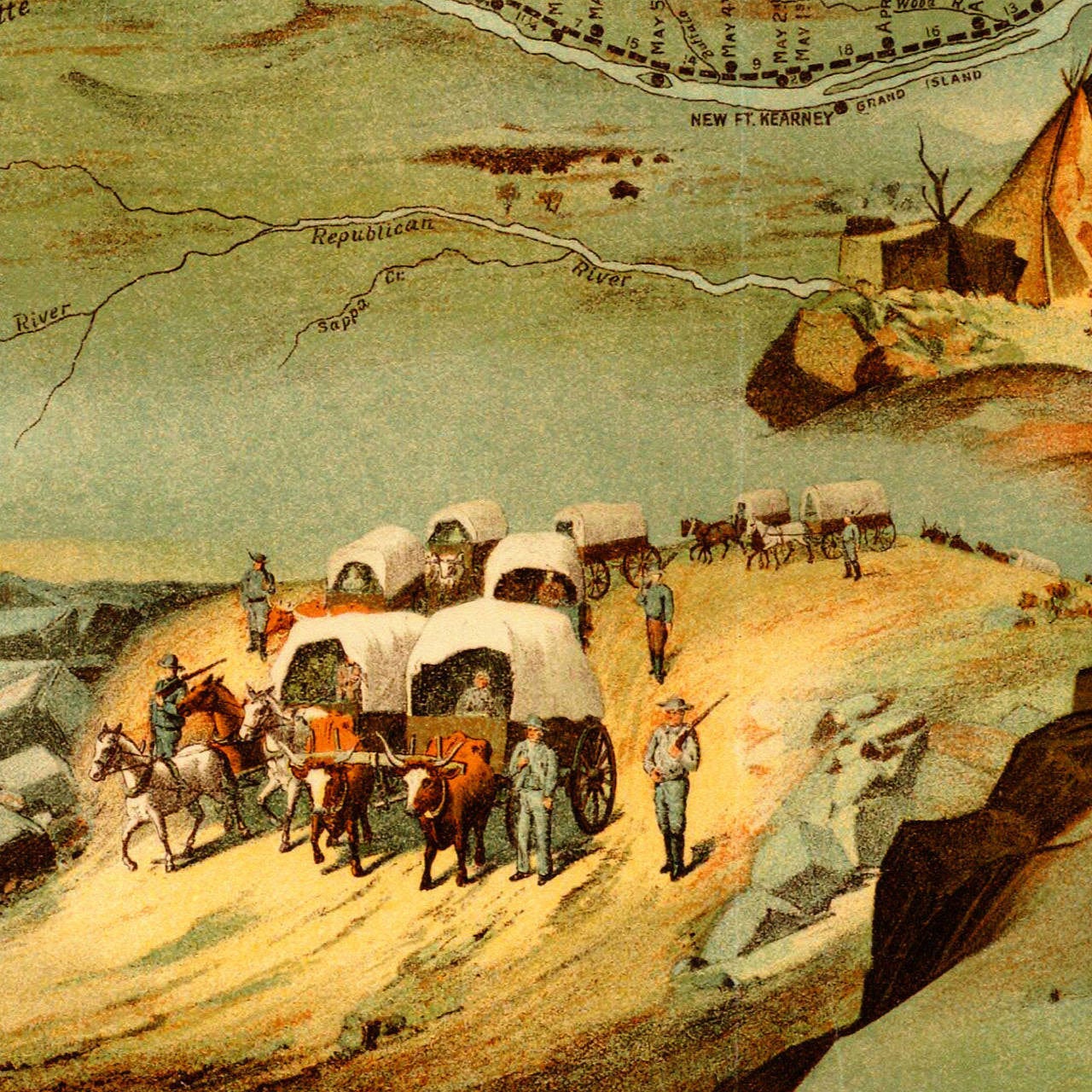

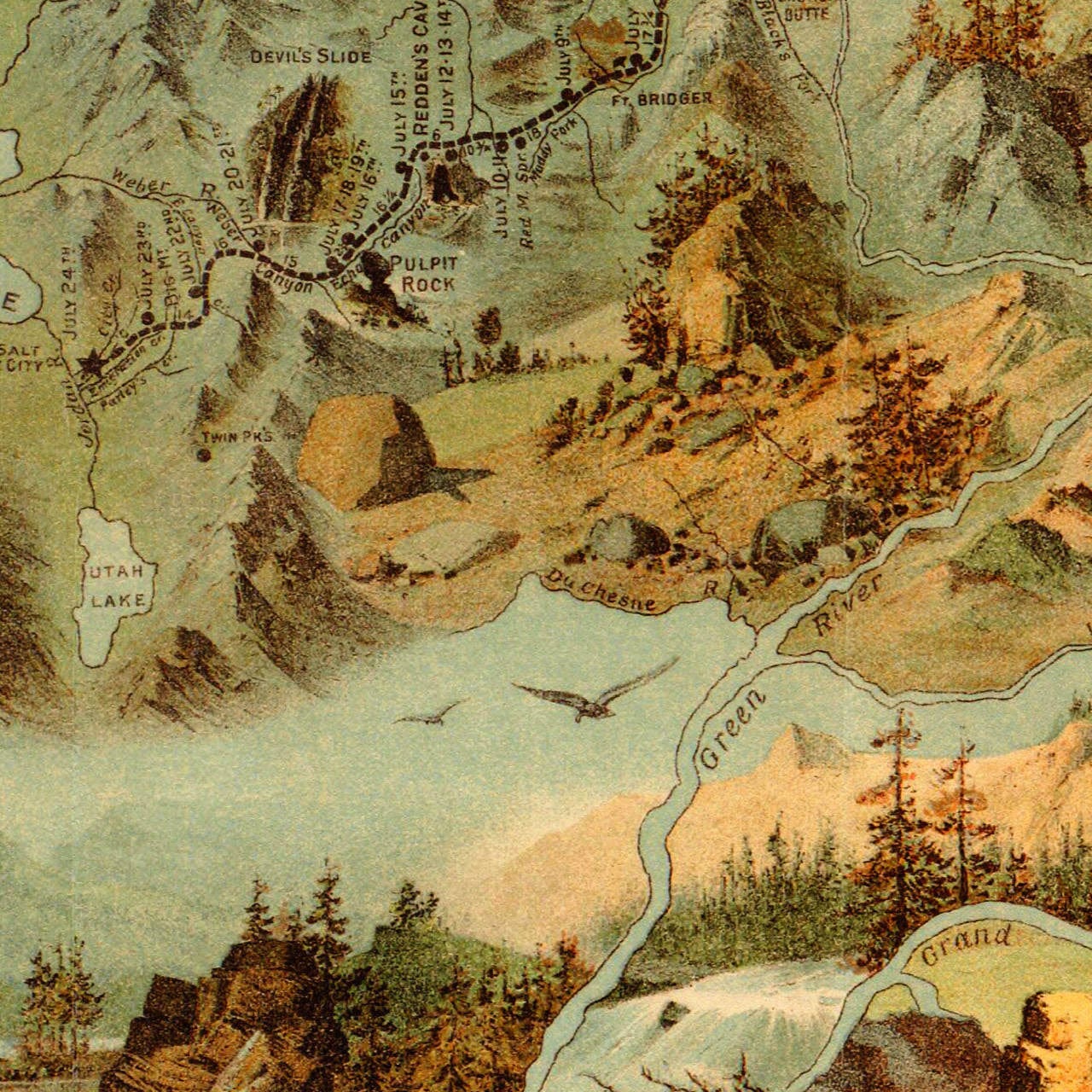

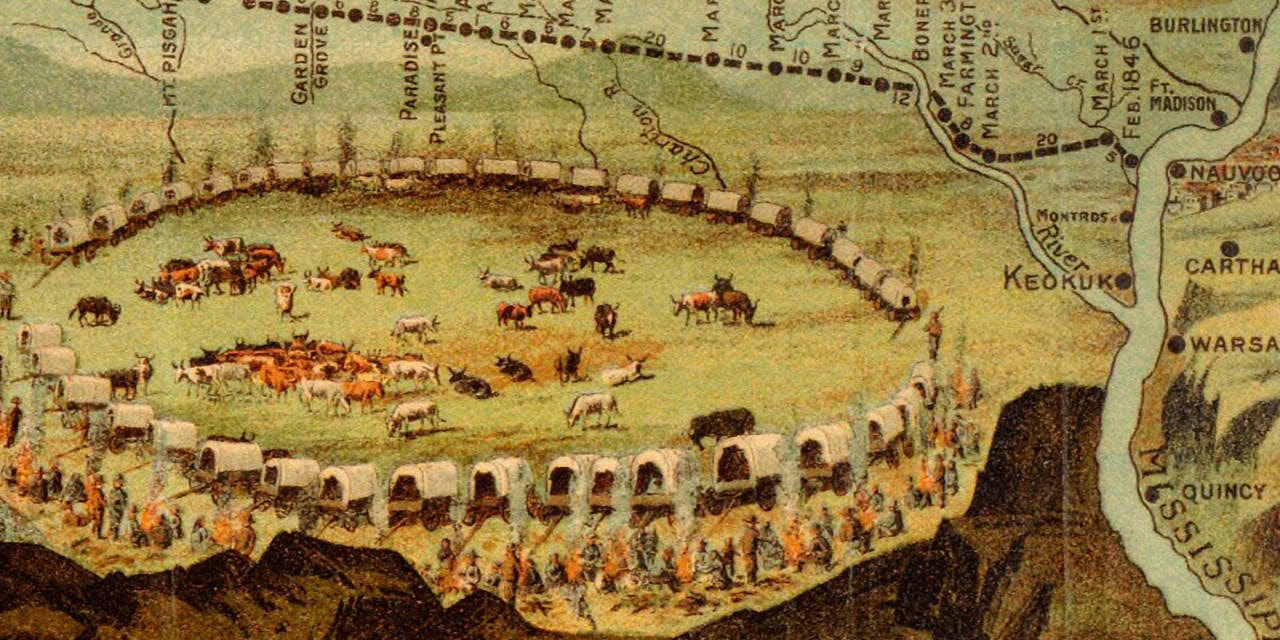

A pioneer acts as the first step toward change—the first to arrive, the first to achieve, or the first attempt. Bold and resilient pioneers fill Utah’s history. For example, many Native American groups lived and thrived in Utah first—long before the Saints arrived—including the Utes, Shoshone, Goshutes, Paiutes, and Navajo. With the construction of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, thousands of immigrants bravely arrived in Utah from China, Europe, and Mexico to work and develop communities. They were among the first from their countries willing to contribute their talents and learn a new language to make Utah thrive. Green Flake was the first enslaved member of the Church to arrive in Utah in 1847. Flake drove the first wagon into Emigration Canyon, and by the time Brigham Young arrived a few days later, he had already planted crops. Seraph Young, a Utah schoolteacher, was the first woman in the United States to vote. She voted on February 14, 1870 on her way to work, decades before the nineteenth amendment was passed.

Assembling from many countries, and driven farther west than the US westward frontier at that time, the nineteenth-century Mormon pioneers felt called to seek and live gospel truths beyond the reach of any one homeland or heritage—both their ancestral homelands and the American homeland that persecuted them. We celebrate Mormon Pioneers as a hopeful representation of a global movement committed to living free of persecution.

Below is a collection of writing and poetry that honors this legacy and invites each of us to consider ways we might take first steps toward new horizons of promise.

Katie Lewis is the digital editor for Wayfare and senior editor for BYU Studies.

Benjamin Peters is a Wayfare Associate Editor. He is also a media scholar, author, and editor interested in Soviet century causes and consequences of the Information Age.

Art by Ben Crowder.

Pioneering

by Sam Benson

In my family, no story is told and retold more frequently than that of Mary Goble. We don’t just save it for Pioneer Day: She somehow folds her way into our family gatherings and Sunday dinners and the artwork on our walls.

With good reason, too. As a boy, I thought Mary’s story was the stuff of legend. I was captivated by the most gruesome details. She acquired frostbite, the story goes, during her thousand-mile trek across the frozen tundra. Upon her arrival in Salt Lake City, a doctor recommended amputating her frostbitten feet. Brigham Young, welcoming the new visitor, wept and blessed her to be able to walk again. Mary, faithful and stubborn, believed him, and the doctor settled on chopping off all ten toes with a butcher’s knife and a saw. She raised thirteen children, my ancestor among them. She walked again.

I think about Mary when I celebrate Pioneer Day. But I often have to remind myself exactly what I’m celebrating. Is it the sacrifice in itself—the lost limbs and lost lives, the home countries renounced, the illness and pain and suffering? Is it the victory: the most successful regulated immigration in our country’s history and the formation of a community in the West? Is it what they were sacrificing for: their faith and the right to live it freely?

Their legacy—what I refer to, in short, as pioneering—is all these and more. Perhaps that’s why pioneer trek reenactments, and many of our Pioneer Day traditions, feel hollow to me. They attempt to honor only one or two of those facets, yet do so in a cheap sort of way, like a Disneyland for martyrs. I’ve written before that Pioneer Day is a celebration of all immigrants, both physical and spiritual ones, who seek a better life. Pioneering then occurs all around us. People sacrifice and suffer. They perform superhuman tasks and they do so in the name of the Divine. They, too, are pioneers.

But so was Mary Goble, of course. In recent years, I’ve come to appreciate the true beauty of her story. Before the frostbite, before the long trek, Mary was just a 13-year-old girl. Her family joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in their native England. She and her family sailed from Liverpool to Boston, trained to Iowa City, then set out in the Hunt wagon train, which eventually merged with the infamous Martin company. They were handsomely outfitted, compared to their handcart colleagues: they had two yokes of oxen, one yoke of cows, a tent, and a wagon. Some combination of poor planning and poor weather pinned them in the Wyoming plains, where unrelenting blizzards drove their progress to a halt. Mary’s mother gave birth; the child died within a month. A four-year-old brother died too.

But amid the tragedy were miracles. Some came as divine intervention; others through the intervention of a brave pioneering sister or brother. Another member of their company recalled running out of strength as he pulled his handcart, but then “the cart began pushing me,” he said. “I have looked back many times to see who was pushing my cart but my eyes saw no one. I knew then that the angels of God were there.”

The Goble family started lightening its load. The cattle gave out, Mary recalled, and an ox was sacrificed for food. When they reached the Sweetwater River, where Mary’s younger sister was buried, a group of young men from the rescue party volunteered to carry travelers across. The historical record is unclear whether Mary hitched a ride through the icy water in her family’s wagon, or if she rode upon the shoulder of some unknown young man. Either way, the river was dotted by frozen rescuers.

They arrived to the Salt Lake Valley after dark in December. The saints, who had done the journey themselves not long before, welcomed them into their humble homes and offered them the scanty food they had. To Mary—who had eaten only flour and water for weeks—it was a feast. “We had to be careful and not eat too much as it might kill us as we were so hungry,” she recalled.

The rest of Mary’s life was hard. Learning to walk without toes was a challenge; giving birth to thirteen children in the wilderness was too. She was a widow before age fifty. Five of her children preceded her in death. She lived through a time of unrest in the Utah Territory, when anti-polygamy raids terrorized the community. “It was very hard times,” Mary recalled.

But Mary held faith in her pioneering. She often remembered her mother’s words: “Polly, I want to go to Zion while my children are small, so they can be raised in the Gospel of Christ, for I know this is the true Church.”

Few commands dot the scriptures as frequently as “remember.” It is more than a passive, cognitive injunction, but an invitation for action. Throughout the Book of Mormon, readers are encouraged to remember their ancestors and allow it to shape their behavior. Often, especially in the Old Testament, the command to remember our ancestors is accompanied with a command to welcome the stranger: “Thou shalt not vex a stranger . . . for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.” “. . . Thou shalt love (the stranger) as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.” “Love ye therefore the stranger: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

I sat in church with a pioneer this past Sunday. I’ll call him David. He came to the US a year ago with his wife, Juana, and two-year-old girl, Tania. (Those are pseudonyms.) They never had plans to come. Years earlier, they left their home, Venezuela, to escape gang violence. But the problems followed them to Colombia, where Tania was born. Just over a year ago, bullet holes in David’s Colombian auto shop sent a message that it was time to head north.

The journey was arduous. They traveled with backpacks, filled only with clothing, food, and milk for the one-year-old. Before long, they dropped the unessentials and filled the packs with milk for the hungry baby. They wore only the clothes on their backs; they accepted food from generous strangers.

The Darien Gap was horrific. David, who carried the baby the whole way, collapsed each night from fatigue. But each morning, he and Juana gave thanks to God and kept trudging along, summiting each hill through the perilous mountainous stretch. During one particularly gruesome passage, David told me, it felt as if an angel was carrying him. He looked back and saw no one. He later felt it was his deceased mother pushing him along.

They kept walking and bussing and hiking, through Costa Rica and Nicaragua and Honduras. The journey took months. At the U.S.-Mexico border, they paid a coyote to help them cross. When they reached a shallow stretch of the Rio Grande, Juana scooped up the baby and David put both on his shoulders. The water, at its deepest level, reached his neck.

Shortly after they arrived on American soil, CBP officers detained them and took them to a Texas processing facility. Juana and the baby were sent to one center; David to another. When they reunited days later, the backpacks of milk—which they had been replenishing through their journey—were almost empty. Juana had seen other mothers with babies who had clearly gone hungry during their weekslong journey. Juana couldn’t help herself from sharing.

Two years later, they are living safely within the US. They found the restored gospel of Jesus Christ here. They were married in a Latter-day Saint meetinghouse and baptized days later. Their life isn’t easy: The threat of immigration enforcement is constant, and it has already struck their congregation. Two members wilfully returned to their home countries this year. Another packed up their whole house ahead of an immigration court date, scared they would never come back. But Juana and David know they are here for a reason. God brought them here, David told me, to find Him. They’ll raise their daughter in the Gospel of Christ, in the true Church.

If Pioneer Day is a day of remembrance, it should also lead us to our own form of pioneering. This celebration of pioneering—of sacrifice, yes, but also of courage, of immigration, of faithfulness, of selflessness—can lead us to see pioneers all around us.

Samuel Benson is a reporter covering food and agriculture policy in Congress for Politico.