Peace Beyond Words

The Language of Peacebuilding

“Tell me about your name.” This is the first task I give to the adult English language students I teach at a university in the United States.

Recently, a young man from the Democratic Republic of the Congo stood in front of our class. He straightened his casual posture, lifted his eyes from the ground to look at his classmates, and said confidently, “My grandmother named me after a Danish ruler. Emrik means king.”

His jaw tensed as he continued, “I didn’t like high school. Everyone did their assignments, but I didn’t.” He recalled a teacher who bluntly asked him, “Why don’t you do your work like everyone else? Do you know who you are?” Emrik said, “I was so mad that I stopped going to school.”

Without school, Emrik had more time at home with his mom. Eventually, he joined her at church and “started talking to God.” “After a few months, my anger went away and I decided to go back to school,” he said, concluding his introduction with this bold statement: “Now I know who God is, and I know who Emrik is.”

His transparency about his resilience and faith in a college setting was refreshing. As an English language educator and a Christian, I’ve spent two decades considering the complex variables that sustain intrinsic learner motivation, both academically and spiritually. For Emrik, it was simple. It seemed that his connection with Deity clarified his ideal self and catalyzed his determination.

Emrik’s alignment of identity, purpose, and choices also illustrates the core dimension of inner peace in a model of peace linguistics for language educators. Peace linguistics interweaves positive psychology and language learning to improve communication among individuals, groups, cultures, countries, and nature. Dr. Rebecca Oxford's multidimensional framework is represented by six nested concentric circles: inner peace is at the center, followed by interpersonal, intergroup, intercultural, international, and ecological layers of peace.

I discovered Oxford’s peace model during the COVID-19 pandemic as I was struggling to adapt my curriculum to meet the fluid needs of students and use the limited medium of language to process their lifequakes.

Virtual learning flattened the distance between my students and me. Zooming into their homes gave me a more holistic view of each learner’s struggles, and they also saw mine.

Suddenly, I felt insensitive making small talk about our favorite dishes when some students were grappling with acute food insecurity. And our travel module about bucket lists became obsolete because we were isolating at home. My students and I became novices juggling the stress of learning, work, family, and health.

These seismic professional shifts and personal fault lines in my family pushed me to acquire a new language: the language of peace. I immersed myself in peace linguistics as a way to navigate complex conversations with more cognitive flexibility and intercultural dialogue.

I embedded these peacebuilding competencies into an intensive eight-week course with English language learners who are pursuing higher education and employment in the United States. Some of these multilingual professionals already work as engineers, educators, entrepreneurs, architects, attorneys, artists, athletes, business managers, psychologists, software developers and veterinarians, yet many of their lives and livelihoods have been disrupted by geopolitical conflicts.

For these individuals, integrating English fluency and conflict transformation skills increases their adaptability. We hone advanced communication strategies to build mutual trust and sharpen creative problem solving. We practice turn-taking, complimenting, apologizing, disagreeing, reducing bias, perspective-taking and active listening skills. Let me offer four anecdotes to illustrate how practicing the language of peace can, in the words of Melissa Inouye, grow our “affinity with all humanity.”

Food is often a conversation ice breaker to build common ground. In the second week of our course, I asked students to describe a food that tastes like home. We discussed the visceral connections between food, family, tradition, and memory. One learner, whose name means modest or simple, was frustrated by this discussion. When I tried to clarify her question, she declared to the whole class, “I have lived in several countries, and I don’t know where I belong anymore.” Her exasperated answer conveyed the complicated intersection of essential human needs for food and belonging.

I didn’t have a useful response to her displacement dilemma. After several days of imagining how this woman toggles among languages, cultures and countries, I pivoted to the nonverbal language of art, which can transmit powerful ideas in any tongue.

Showing this student pixelated portraits helped her see that each part of her creates a singular whole. I acknowledged that while her multicultural background may create tension, her multilingual skill set also gives her a higher threshold for ambiguity and a wider aperture of empathy. She appreciated my efforts to visually validate her cross-cultural identities.

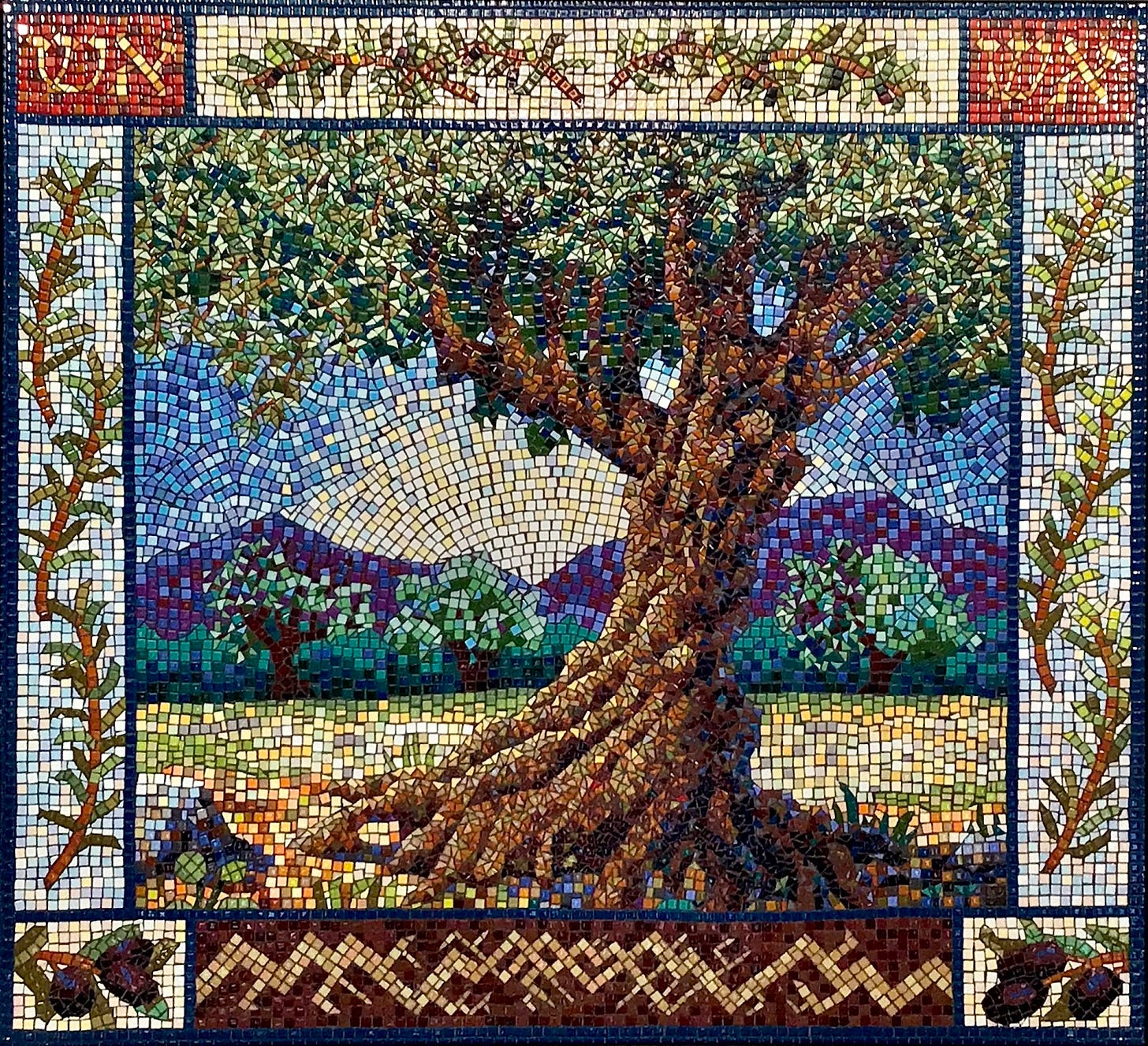

I translated these secular insights from fresh spiritual clippings that were inspired by a mosaic of an olive tree based on the allegory of God’s global transplanting project (Jacob 5). Just as the artist handcrafted and fit every piece of this stunning work, I envisioned the Lord of the vineyard laboring side by side with each of us to graft our unique identities from distinct roots of cultural heritage, language background and lived experiences. If we feel uprooted, we can practice self-compassion by holding each facet of our singular mosaic.

Over the next few weeks, I observed this woman’s emotional agility increase as she voiced her opinions and developed supportive friendships with younger classmates from Ukraine and China. Intrapersonal peace is a wellspring for belonging and resilience in interpersonal relationships.

During an unconscious bias workshop, I paired myself with Saif, a talkative man from Jordan. We reviewed the conversation prompt, “When have you assumed something about someone and later realized you were wrong?” He graciously encouraged me to answer the question first. It felt like a risk to speak honestly to Saif because most of his class comments were jokes.

In a moment of vulnerability, I told him about my hurtful assumptions that my daughter’s academic challenges were tied to her lack of effort. After years of friction about her high school grades, we found that my daughter’s learning hurdles were part of an undiagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Discovering how my daughter’s kaleidoscopic brain worked led us to better tools and support for her education and emotional wellness. This new path refilled a reservoir of compassion in our relationship.

Saif was uncharacteristically quiet. I wondered if he understood me. Following an awkward pause, he mirrored the painful journey my daughter and I had navigated together. He offered his perspective of his brother who had also struggled in school for many years. He described how his father became less reactive and more empathetic with his brother. Eventually, his brother began to thrive in school and life. He smiled as he concluded, “Now he and my father laugh together more.”

While this young man’s vocabulary was limited, his emotional fluency was advanced. His witness of his family dynamics fueled my hope that the language of peace could heal wounds in my home. Saif’s unexpected gift of solidarity showed me that when we are willing to be seen and see others, we build bridges of understanding toward positive peace.

In these Zion moments of seeing eye to eye (Isaiah 52:7-8), I can hear the energizing voice of Dr. Kate Holbrook, who said, “Watching God’s love through the Holy Ghost transcend linguistic and cultural barriers fills me with hope. That miracle makes me think that every good thing is possible.”

In a global literacy discussion about how to break stereotypes, I highlighted the work of Malala Yousafzai, an education activist and Nobel Peace Prize recipient. Enayat, a well-educated engineer from Afghanistan, raised his hand. I tensed, uncertain how this articulate student would interject. A quick parade of his potential rebuttals rushed through my mind, but I nodded to welcome his comment.

Enayat, whose name means kindness or grace in Arabic, gently corrected me. “I think you said her name wrong.” I inhaled relief and exhaled curiosity.

“How do you say Malala’s name?” I asked him. He proudly wrote Malala’s name in Arabic to illustrate where his intonation differed from mine. I looked at his elegant script and echoed his pronunciation.

I asked him if I could keep the scrap of paper to help me practice. As I held this new information, I realized how he subtly lifted the blinds of my own bias. I had assumed that this Afghan man would object to Malala’s advocacy for girls’ education.

Instead, his intentional gesture to honor her name reinforced our shared humanity. Enayat’s soft feedback opened my mind, which I believe is a prerequisite for uncovering our limiting beliefs about others and ourselves. Language amplifies our views, which can dehumanize or rehumanize us.

The next day Enayat approached me before class. He said, “I’m terribly sorry. I made a mistake. I researched the topic further, and I was wrong; you were right. We pronounce her name differently in Afghanistan than people do in Pakistan.”

I was speechless.

Again, he shattered my cultural and gender stereotypes. His proactive introspection and apology were a master class in peace linguistics. In our Latter-day Saint vernacular we use a tidy term for such advanced social skills: repentance. These micro speech acts can yield universal fruits of reconciliation across all languages to repair fractures and replenish relationships among people, groups, cultures and nations. Embracing restorative practices is centered in recognizing our “infinite dignity.”

Oxford’s final ecological dimension of peace attunes us to our environment. To help learners rejuvenate their brains and build descriptive vocabulary, I assign students to go outside and journal about what they perceive with their five senses. This psycholinguistic activity can improve emotional regulation and increase observation skills, which enhance nonviolent communication. Grounding ourselves in vital ecosystems may also yield healthier human interdependence.

Tomoyo, a reserved student from Japan, explained that she loved her name because it was a gift from her parents. During our mindfulness practice, I sat near Tomoyo in the shade of shimmering gold leaves that danced in the afternoon sun. I leaned over and showed her the only Japanese characters I knew, 木漏れ日, which translates as “sunlight shining through the trees.” Her whole face lit up in surprise as she read the characters, gazed upward at the trees, and nodded in awe. We relaxed wordlessly in the gentle breeze and warmth of the sun. Our Heavenly Parents create “infinite touchpoints” to infuse our eyes, ears, noses, mouths, hands, minds, and hearts with wholeness.

In contrast, the ancient Nephite civilization was rocked by destructive natural disasters after the brutal crucifixion of the earth’s Creator. Following Christ’s resurrection, in a radical act of compassion, the scarred Savior lovingly healed every child, woman and man who survived the catastrophes. Then Jesus invited them to partner with him in reconstructing a sustainable society founded on his blueprint of peace.

To these survivors of intergenerational conflict, the resurrected Redeemer extended a revolutionary call to action: “Blessed are all the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God” (3 Nephi 12:9, emphasis added). Jesus’s one-word variation from his Sermon on the Mount is inclusive: all. The living Lord wants to bless all peacemakers from every nation, kindred, tongue, and people. We begin to make peace by calling all people children of God. When we see ourselves and others as the offspring of Deity, we all sow seeds of moral creativity to produce vertical and horizontal harmony from our divine diversity.

Like Emrik, who was named for a Danish ruler, we are christened with the name of a monarch from a distant time and country when we are reborn into the family of Jesus (Mosiah 5). Immersed in his grace, we can grow up into Christ’s complete character and practice speaking with the tongue of angels (2 Nephi 32:2-3).

Ultimately, our inner peace flows outward as we integrate our discipleship, words and choices. Daily spiritual calibration with God synchronizes our minds, hearts and mouths so we can “meet every situation of life,” as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “with an abounding love.” How we choose to embody the name of the Prince of Peace will transform our capacity to convey his healing peace across every dimension of our human and divine relationships.

Emily White is an English Language educator who builds peace bridges one conversation at a time. Emily loves collecting small shells, tiny art, and big ideas.

Art by Paige Crosland Anderson.