Bishop Levy’s heart dropped when he saw Oskar the Miser walk through the meetinghouse doors early one morning on the first Sunday of the month to pay his fast offering. By longstanding agreement, the Bishop handed the first fast offering of the day to Lazar the Blind Beggar, and Oskar’s appearance did not bode well for the man. Despite his significant wealth, Oskar lived on a diet of cabbage soup—cooked from the same head of cabbage all week—and he calculated his offering very literally. It made Bishop Levy’s stomach growl just thinking about all the food the Miser’s meager offering wouldn’t buy.

Still, as bishop, it was Levy’s duty to accept whatever was offered, even if it was only two tiny, all-but-worthless coins. “Thank you, Brother Weiner,” he said as he took the envelope. “May the Lord reward you tenfold,” he added. Given the starting point, the bishop wasn’t sure that such a promise counted as a generous blessing or a de facto curse.

Oskar the Miser squinted at the bishop and Bishop Levy sighed. The last time he had promised Oskar earthly blessings for his minimal act of altruism, Oskar had found a zloty on the street on his way home. Though the coin would only cover half the cost of bus fare, it was worth fifty times as much as the Miser’s offering. Rather than rejoice over this tiny bit of good luck, the old man had returned to take the Bishop to task for reckless overspending of God’s blessing money.

Bishop Levy tried not to make a habit of offending ward members. He even kept a little notebook of topics that might set different individuals off. No matter what Saul Gronam’s calling happened to be, for example, you had to show it unreasonable respect or he would feel personally slighted. Leah Kantor’s feelings could be hurt, and her opinion of you would certainly suffer, if you didn’t at least pretend to be interested in art and music. For Isaac Peretz, it was safest to avoid politics, economics—and maybe even, just to be safe, religion. It was dangerous, with Mirele Schwartz, to talk about anything that could have gone better. But Oskar the Miser? All the sensitive topics with him went back to money, but after taking two pages of notes on the specifics, Bishop Levy realized he was wasting perfectly good paper. If it wasn’t one thing with that man, it was another. You couldn’t dodge his complaints, only try to guess which particular topic would start the next scolding. Would it be the free soap in the meetinghouse bathrooms? The lack of security to prevent the theft of hymn books? Even if he walked away, he could easily come back shouting because he had found a lost coin.

This time, Oskar did not wait to air a grievance. “You know that fasting is no problem for me, bishop,” he said. “But this fast offering is a terrible business. What’s the point of asking us all to sacrifice for the hungry if you’re going to turn around and serve the whole congregation a free breakfast!” Ah yes, thought Bishop Levy. They were back to the issue of excessive portions of sacrament bread. Oskar grimaced. “People keep saying God is just, but then they ask you to invest as if he were plain wasteful!” He wagged a finger in the Bishop’s face. “I tell you: these sorts of logical contradictions are driving learned men from religion!”

With that, the old man shuffled away—just in time for Bishop Levy to notice Lazar the blind beggar approaching the meetinghouse door. He had half a mind to duck into his office to add some money to the envelope, but Lazar was very particular. Whenever Bishop Levy tried to convince him to accept a regular payment, he insisted that beggars lived by the grace of God and refused to accept one zloty more than divine chance allotted him.

What to do, though, on a week when divine chance hadn’t allotted him a zloty at all?

Lazar was smiling broadly as he approached. “Let us see, good bishop,” he called, “what the Master of the Universe has granted me today!”

Bishop Levy placed a hand on the blind beggar’s shoulder and let it linger, he hoped consolingly, as he handed over Oskar’s envelope. Lazar put his hand in and the smile on his face turned to a look of puzzlement. Bishop Levy watched in pain as Lazar felt carefully around the edges of the envelope, no doubt certain that he had missed some folded bill or hidden coin beyond the two tiny groszy Oskar actually, truly, and in all sincerity donated each month.

After making a thorough investigation, Lazar stopped feeling around the envelope, put a hand in his pocket, and withdrew two shiny zlotys, which he placed in Oskar’s envelope. “Bishop,” he implored, “will you take this and give it back to the donor today?This person is surely in more grievous need than I.”

And with those words, Lazar walked off into the chapel, leaving Bishop Levy standing alone in the hallway, astounded. More grievous need than I? On its surface, the idea was laughable. The miser was quite wealthy and grew wealthier with each week, even if he did suffer from the economic equivalent of crippling constipation. If most people were asked to describe him, the challenge might stretch their vocabularies beyond the sort of words a person normally used within the confines of God’s house. With a big enough vocabulary, you could call Oskar curmudgeonly, misanthropic, or avaricious. But no matter how creative a person got, the bishop sincerely doubted the word needy would come to any ordinary mind.

But ah, the bishop realized, Lazar the blind beggar did not see as other men see. Bishop Levy saw two tiny coins in an otherwise empty envelope, but Lazar saw something even smaller. Like God himself, he truly looked upon the heart!

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

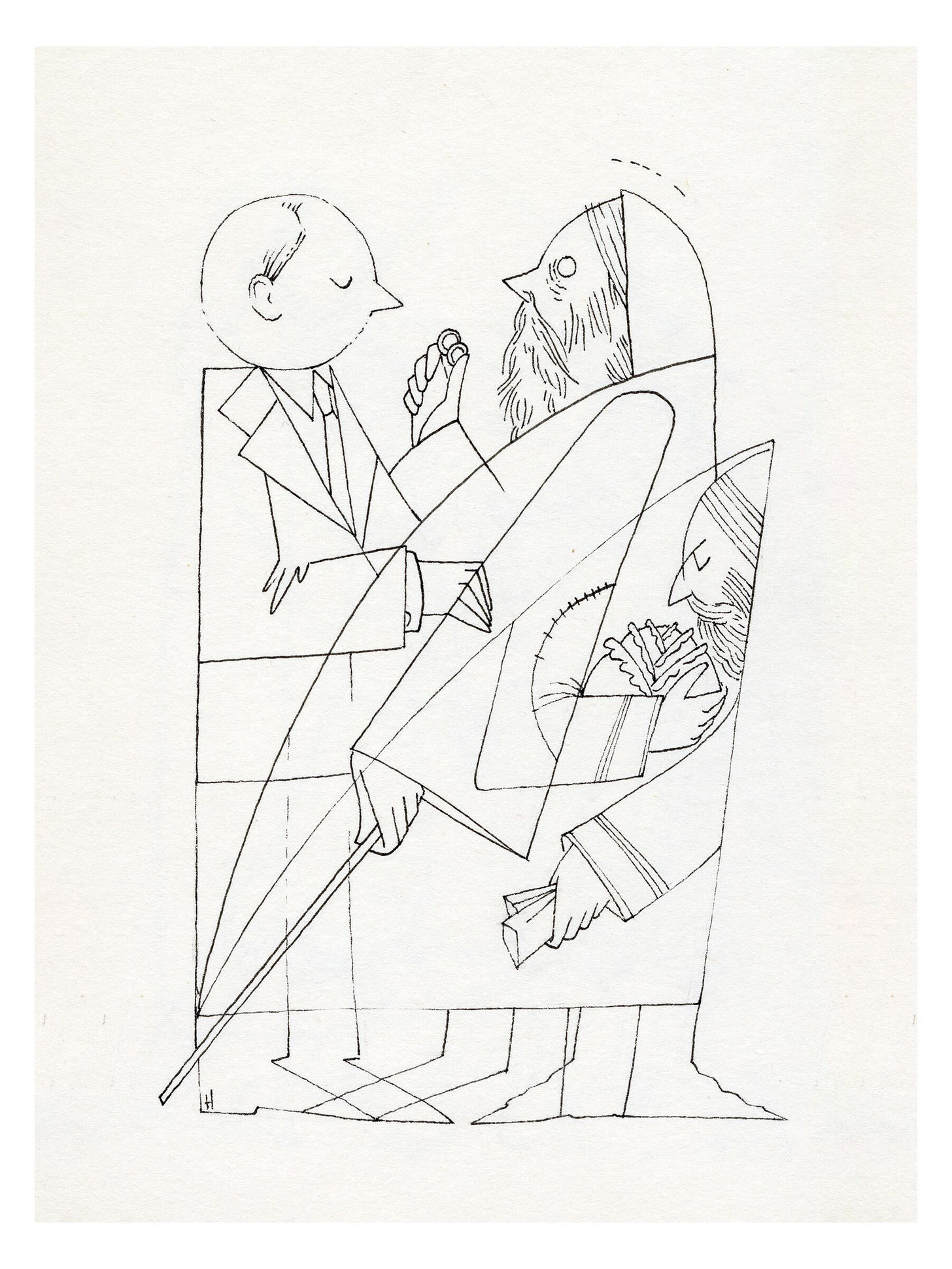

Artwork by David Habben.