Ordinary Stardust

An Interview with Alan Townsend

In this episode of BYUradio’s Constant Wonder, host Marcus Smith speaks with Alan Townsend, a biogeochemist and the author of "This Ordinary Stardust: A Scientist's Path from Grief to Wonder." Townsend’s wife and daughter were diagnosed with unrelated brain cancers. One survived, while the other did not. This father and husband then had to choose how to how to put back the pieces, both of his life and of his view of a universe that once seemed to him so clear and logical.

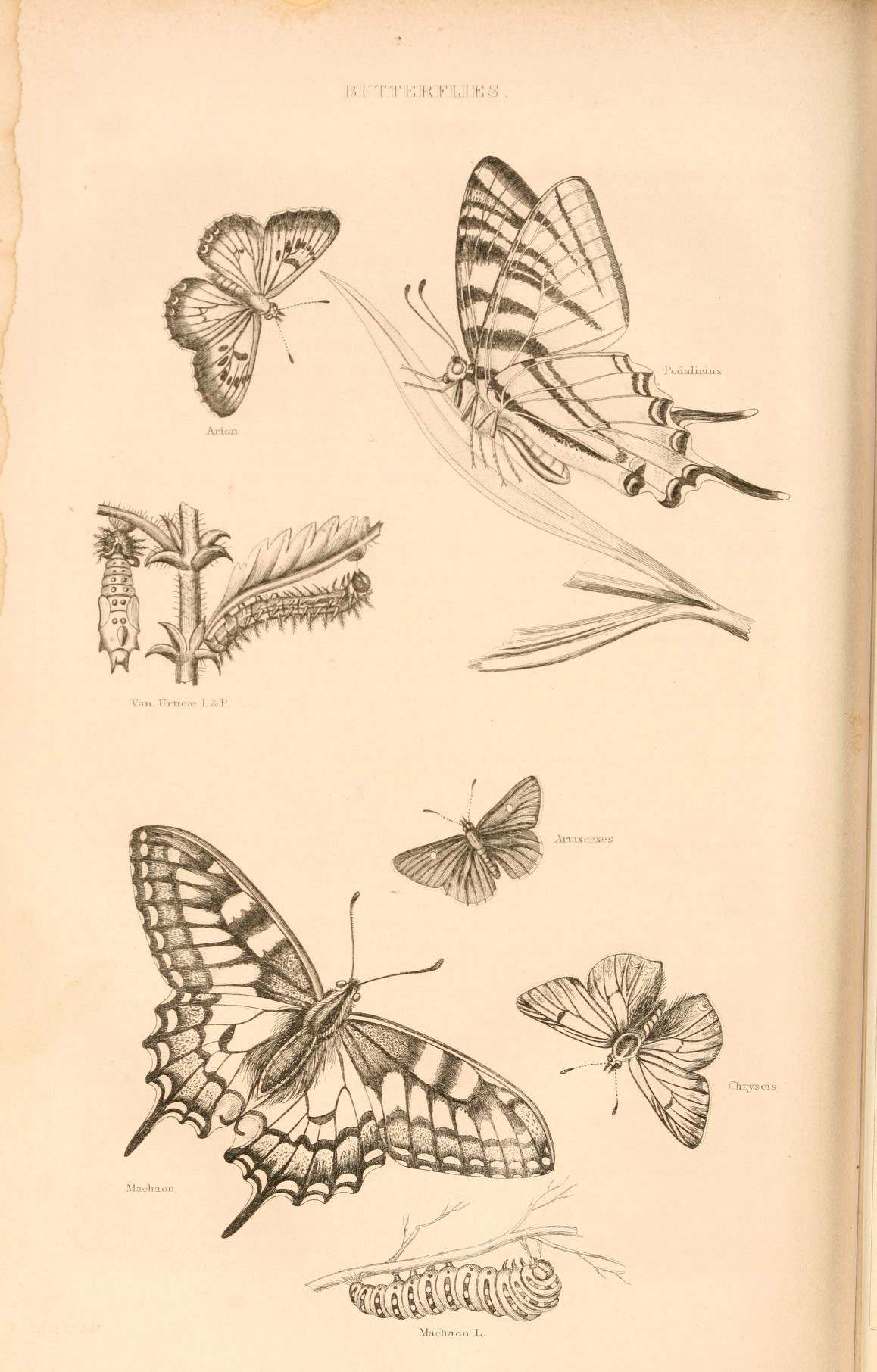

Marcus and Alan discuss the science of the well-known caterpillar-to-butterfly metaphor, which Alan uses in conjunction with the concept of stardust—the make-up material of every single thing in the universe—to describe what he's learned from this excruciating trial.

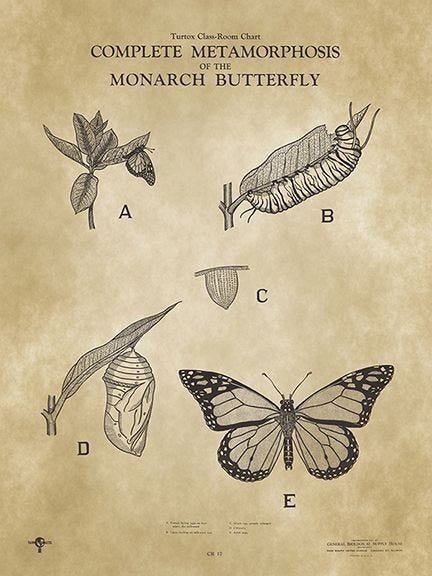

Alan: When a caterpillar enters the cocoon and transforms into a butterfly, it literally does, for the most part, dissolve. Its own digestive enzymes start eating it from within and not everything goes away. There are some parts of the caterpillar's body—aspects of legs, some of the gut track, a few things that kind of make it through, but most of it just gets melted down into this chemical soup, this goo, [and] within that are these cells, called imaginal cells, or sometimes imaginal discs. Ultimately, as everything dissolves, they kind of take over, and they are these tiny cellular sources for rebuilding what is largely an entirely different animal. That that can happen is kind of crazy, right? That just works biologically. The cells themselves effectively hold the memories of the caterpillar. They're transmitting information for the adult winged bug from its youthful state, and carry the information forward for building this whole new bug.

Prior to us understanding the biology, butterfly metamorphosis really was thought to be by some, an example of resurrection, an example of that whole principle, because nothing else seemed possible. It's just like, well, this thing is dying and then it comes back to life. How can that be possible? And for me, it just became a metaphor that life can turn really messy and really small and seem utterly disastrous and seem to have no form or function or possibility of a bright future and then, unaccountably, it can still happen.

Science shows us that in all kinds of examples. The butterfly is just one of those examples where the reality of the world that we share is one of death and destruction and renewal and miracle—all the time. You know, a volcano comes through and just obliterates a place, and it just seems like a moonscape of ruin and then, the next thing you know, a few decades later, there's this remarkable forest growing on it. But the butterfly example was a particularly potent metaphor of feeling like life was really just dissolving for me and my family—and having moments of thinking there was no escape from that—and then realizing that there can be, and that that escape can still have a lot of beauty in it.

To connect to stardust—that's my own profession—to study these elements and how they work their way through life in the world, that's what a biogeochemist does. What I found comfort in, and even just delight and wonder far before this happened for my family, is just the fact of how it just connects us all, that the elements that form everything we know, form ourselves, [form] everything in the whole world—they were all created long before any of us were around, billions of years ago. Yet here they all are, and the world is a constant recombination of those elements into new forms. So, I like to think about stardust as our source of immortality and as a way in which all of the stories of the world interweave with each other, and they enter us for a while and then they move on to something else.

Marcus Smith: For somebody who doesn't have a traditional belief in God, you've just given us a definition of a kind of immortality. So, there's something divine or miraculous about that reconstitution of the elements. But then you quote from Corinthians on talking about faith, hope, and love. What's the bridge for you there, the connection?

Alan Townsend: Faith, hope, and love are things that we all experience as human beings in one way or the other. When we disintegrate and our elements go on to build the next thing, love is the one thing that can truly enter deep time. Is there a rational explanation for that? Is there an atomic explanation for how somebody's elements will continue to carry love somewhere else? Of course not. But it is a way I think about love as an enduring feature of humans and not just humans [but] of many creatures on the planet; and somehow the miraculous product of these elements that come together continues to express itself again and again and again, no matter how they're combined.

This conversation excerpt has been edited for clarity and length. Listen to the full interview below.

Marcus Smith is the host of Constant Wonder, produced by BYUradio.

Art provided by Biodiversity Heritage Library