This post is part of a collaborative series between Wayfare and Latter-day Eloquence: Two Centuries of Mormon Oratory, which is available for pre-order here. (Use code S26UIP for a 30% discount!)

Across its two-hundred-year history, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (and Mormon culture writ large) has developed an impressive tradition of public address, much of which has been recorded and collected, but relatively little of which has been studied academically, and none of which has attempted to capture the full range of the Latter-day Saint speaking voice. Our volume and this series attempt to fill that gap by providing a vital sampling of sermons and speeches that offer primary works for students and scholars of Mormonism, of American culture, and of religious rhetoric, as well as for anyone interested in the faith’s rich and surprisingly diverse tradition of eloquent oratory.

Since the Church maintains no professionally trained or paid clergy at the local level, no schools of theology, and no separate priestly class, it has no concept of what other religions call homiletics, or the art and theory of preaching. So one might presume there is not a strong culture of preaching or public oratory in the Church, but we find precisely the opposite. The Church’s radically democratic structure, lay ministry, geographically bounded wards, and volunteer callings make it an entire universe of constant speechmaking by all kinds of orators, skilled and otherwise. Members are frequently required to give talks or sermons in front of entire congregations, including prepared messages at assigned meetings, open-mic testimony meetings once a month, and frequent devotionals, firesides, conferences, camps, and other events—to say nothing of public prayers, ordinances, rituals, priesthood blessings, and other speech acts that play a central role in the maintenance of Latter-day Saint life.

Almost as soon as they can walk and talk, young members of the Church enter Primary, where they are invited to prepare short talks for large groups of fellow children. They typically deliver these addresses into microphones while standing behind lecterns. At age eleven or twelve, they enter the youth program, where they are invited to prepare whole lessons and give more talks, sometimes to the adult congregation. Beginning as early as age eighteen, active Latter-day Saints are encouraged to join a robust missionary force, leaving home to travel the world, two by two, to preach in homes, parks, and streets. Frequently called to leadership positions, these missionaries organize and conduct meetings, administer rituals, pray publicly, and give several lessons and talks each week in addition to their extemporaneous preaching.

By the time they arrive home from their missionary service, typical Latter-day Saints have become seasoned—if not always well-trained—orators and leaders, poised to continue contributing to their local congregations as part of the Church’s vast lay ministry. In these roles, Church members are expected to conduct meetings and trainings, teach and offer counsel, and speak frequently to audiences ranging from a few individuals to a few hundred or even a few thousand people.

All told, Latter-day Saints are expected to speak and preach frequently and publicly on topics of significance, often with little notice, from a young age and throughout their lives. It is not an overstatement to claim that members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are likely to have spent far more time than the average person behind a lectern or pulpit delivering speeches, lessons, sermons, and prayers before large audiences.

As scholars of rhetoric—or the art, theory, and practice of communication—we find this phenomenon fascinating. Surely this abundance of public-speaking opportunities accounts for part of the success of Latter-day Saints in the worlds of business, government, and education. We also understand that no number of fine examples of Mormon oratory have prevented an equal amount of boring, uninspiring, or cliche sacrament meeting talks.

Either way, however, Latter-day Saints exhibit a reverence for the spoken word and its centrality to their lived experience. They demonstrate a great love of eloquent orators, like the late Jeffrey R. Holland and the charismatic Dieter F. Uchtdorf. They also show a profound respect for more austere speaking styles, like that of Bruce R. McConckie or Spencer W. Kimball.

Then there’s the famous statement of Brigham Young, who declared: “When I saw a man without eloquence, or talents for public speaking, who could only say, ‘I know, by the power of the Holy Ghost, that the Book of Mormon is true, that Joseph Smith is a Prophet of the Lord,’ the Holy Ghost proceeding from that individual illuminate[d] my understanding, and light, glory, and immortality [were] before me.”

Finally, there is the prodigious spectrum of non-institutional Latter-day Saint voices that have contributed to this tradition. From women and minorities to intellectuals and non-conformists, Mormons are anything but monovocal, as our anthology seeks to demonstrate. Believers and critics alike seem to understand the importance of this Book of Mormon truth, that: “the preaching of the word . . . had [a] more powerful effect upon the minds of the people than the sword or anything else” (Alma 31:5).

In this Wayfare series and in the anthology, you’ll encounter Joseph Smith’s legendary King Follett Sermon, one of Melissa Inouye’s Maxwell Institute lectures, and a Bancroft Prize acceptance speech by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. You’ll also encounter or re-encounter Truman G. Madsen’s audio-recorded education week addresses on Joseph Smith, Francine Bennion’s “A Latter-day Saint Theology of Suffering,” and Orson F. Whitney’s “Home Literature” address, with its famous call for “Miltons and Shakespeares of our own.” You will also find that, despite their richness and diversity, these speeches and others in the series and anthology all openly confess or deeply imply a central commitment to the Savior, or at least to the importance of the restored gospel as an influence on the speakers’ lives. May you enjoy reflecting on the significance of public speaking in Latter-day Saint life through this series, as well as its endless yearning for divine eloquence.

To receive each new post in the Oratory series, first subscribe to Wayfare and then click here to manage your subscription and select “Oratory.”

Richard Benjamin Crosby is a professor in the English department at Brigham Young University, where he specializes in the history, theory, and criticism of rhetoric. His essays have appeared in his field’s top journals, and he is the author of American Kairos: Washington National Cathedral and the New Civil Religion.

Isaac James Richards is an award-winning poet, essayist, and scholar of rhetoric. He has also taught classes in the BYU English Department, Honors Program, and School of Communications.

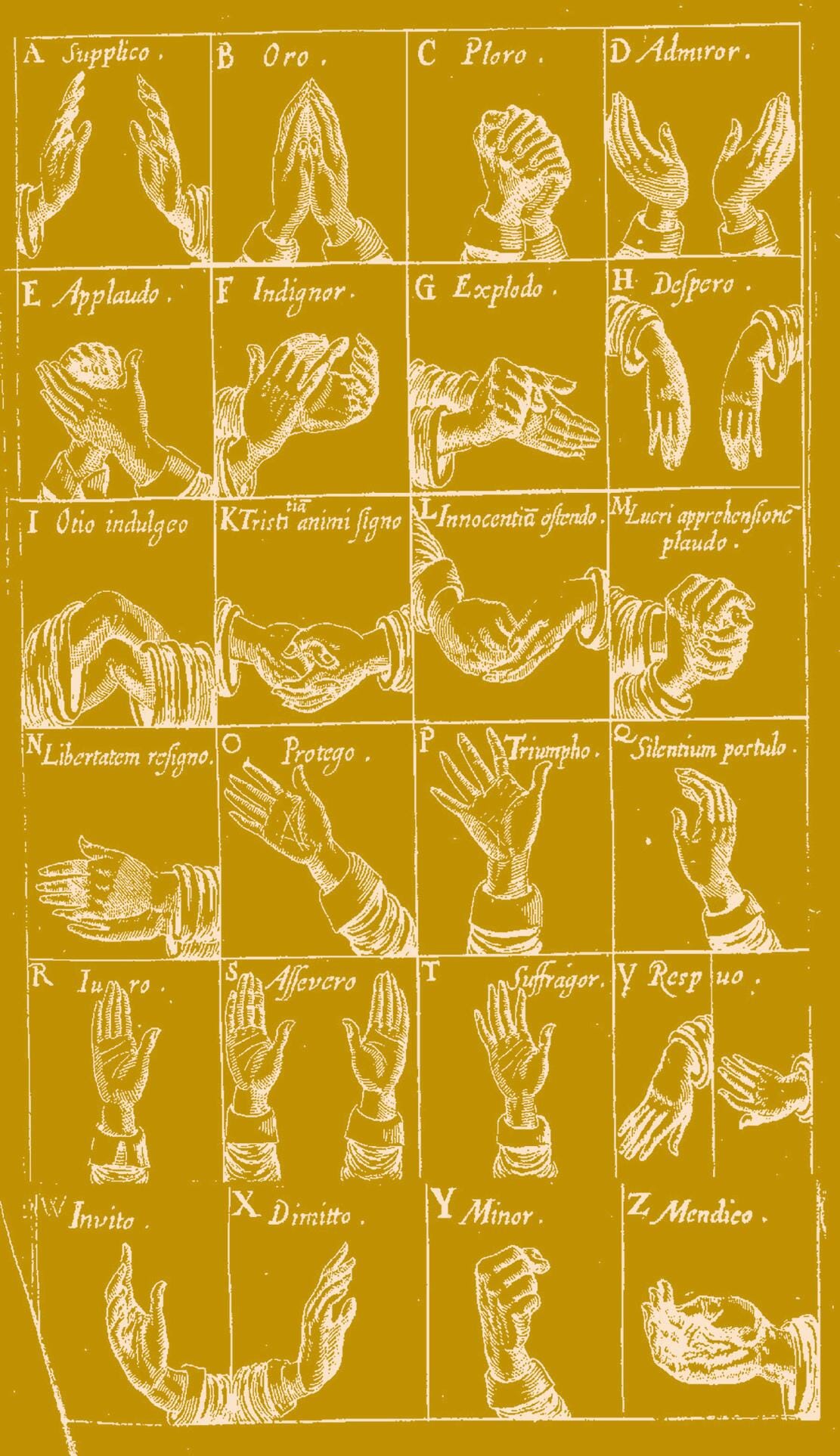

Illustrations from Chirologia; Or the Natural Language of the Hand (1644) by John Bulwer. Hand gestures have long been used to great effect by public speakers to convey or emphasize meaning. In certain cultures, specific hand meanings hold well-known meanings.

Looking forward to this anthology!