Purchase Latter-Day Saint Art: A Critical Reader, published by Oxford University Press.

For most of my life, I have viewed “opposition” as a negative thing: there is good, there is bad—seek the good, avoid the bad. I understand why I was taught this way as a child, and I have compassion for my younger self who wanted to tidy the world into neat categories and simplistic platitudes. However, as I began seriously studying the Humanities—where the complexities, nuances, complications, and paradoxes of history, culture, and faith are excavated—I realized I would need to rethink the black-and-white, all-or-nothing approach I previously found so comforting. I found visual art, particularly the work of Latter-day Saint artists, especially helpful as I grew up and out of traditional binaries to instead hold space for tension and the unresolved. I now understand Lehi’s words to his anxiety-ridden son, Jacob, differently: “For it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things” (2 Nephi 2:11). There is opposition within our theology, within our culture, within ourselves—and that is exactly how it is supposed to be, otherwise “there would have been no purpose in the end of its creation” (2 Nephi 2:12).

Not only does art itself rely upon opposing contrasts to realize its form, its reception, distribution, and symbolism tells us something about the dynamic nature that exists within ourselves. This is why the rigorous study of art objects—and their histories—is so vital: our relationship to our visual and material culture is about our relationship with others, the institutions we support, and even our relationship with the Divine. Looking at art can indeed be a casual appreciation of beauty, but understanding it, testing it, creating it enlarges our capacity to make peace with the “opposition in all things.”

Art outsources our greatest fears, anxieties, hopes, and questions into tangible objects; because they are outside of embodied existence, we can begin to approach even the most sensitive subjects and important conversations.

This is all art can be, but whether it is or not depends on the tools in our toolbox. Critical thinking, thoughtful inquiry, engaged empathy, and even play are what we need to get the most out of our art. Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader gives us such tools.

The Center for Latter-day Saint Arts’ impressive new volume, Latter-day Saint Art: A Critical Reader (Oxford University Press), makes an ambitious and long-awaited contribution to the fields of religious studies, art history, visual and material culture, and cultural theory. Both intellectually and physically substantial with over 600 pages and nearly 250 reproductions, this edited collection brings together 22 authors from a myriad of disciplines. Scholars of history, art, film and media studies share space with artists, museums directors, filmmakers, curators, theologians, and journalists who span the spectrum in their relationship to Mormonism.

The result? A bustling neighborhood of thinkers, where visiting readers converse with both seasoned scholars and intrepid newcomers in their collective effort to expand and multiply definitions of Latter-day Saint art.

As each contributor develops their own answer to the question, “What has been accomplished in the field of LDS visual art, and why does it matter?” (viii), a striking array of responses emerge. With such an eclectic line-up, a range of topics and methodologies is to be expected. This includes (but is not limited to): the theological underpinnings of Mormon art (Terryl Givens); Latter-day Saint architectural design and temple art renewal (Colleen McDannell, Josh Edward Probert, Rebecca Janzen); modernism, art education in Utah, and contemporary Latter-day Saint art movements (Glen Nelson, Menacham Wecker, Analisa Coats Sato, Chase Westfall); race and gender in Latter-day Saint art, education, and experience (W. Paul Reeve, Jennifer Reeder, Carlyle Constantino, Amanda K. Beardsley); Mormon subjectivity and embodiment in film (Randy Astle, Mason Kamana Allred); the Mormon landscape and public image as defined through monuments, cartoons, and photography (Mary Campbell, Nathan Rees, James Swensen); and the construction of global Mormon identities through immigrant converts and globetrotting artists (Ashlee Whitaker Evans, Glen Nelson, Heather Belnap, Linda Jones Gibbs, Laura Paulsen Howe).

Previous publications, like Lorin Wheelwright’s Mormon Arts, Volume I (1972), Robert Davis and Richard Oman’s Images of Faith : Art of the Latter-day Saints (1995), Artists of Utah by Vern Swanson (1999), Robert Olpin and William S. Seifrit, Herman Du Toit Masters of Light: Coming unto Christ Through Inspired Devotional Art (2016), Laura Allred Hurtado’s exhibition catalogue Immediate Present (2017) and the BYU Art Department’s A 15-Year Expanse, Volume 1 (2020), have brought attention the quality of creation amongst Latter-day Saint artists in past decades. However, until recently, the study of Latter-day Saint art has largely remained a hermetic niche within academic scholarship, understudied and underappreciated.

Latter-day Saint Art seeks to overcome the overlooked by meeting the “need for more theory, criticism, and investigation of [Latter-day Saints’] place in history” (viii). This deployment of rigorous scholarship around Latter-day Saint topics follows broader trends in the field of Mormon studies and adds a unique perspective to the current discourse surrounding the way a religion and its objects fashion cultural identity.

In their introduction, editors Amanda Beardsley and Mason Kaman Allred articulate the scope of their project:

Taken as a whole, our volume is . . . inevitably, reductive in its focus on visual art to define a religion. In this self-conscious approach it generates unprecedented depth, a diversity of voices, and an equal expansion of our vision of what Mormon art was, is, and can be”(3).

Limiting itself primarily to a treatment of visual art—namely “painting, sculpture, photography, film, architecture, exhibitions, and various material cultural products”—the project can more easily accommodate breadth and depth within those categories, effectively demonstrating what a specific study of art can tell us about a particular (or peculiar) religion (10).

It is difficult to fault a project that is so self-aware. The editors and collaborators are both clear-eyed and constrained about what this project is, what it is not, what it can and cannot reasonably do, and what it should spur next. In their foreword, Glen Nelson and Richard Bushman—co-founders of the Center for Latter-day Saint Art and formidable scholars in their own right—outline their criteria for the project’s success: “This book will have succeeded if it provokes a responding barrage of additional scholarship and art criticism” (x). Likewise, the primary goal of the volume, as outlined by Beardsley and Allred, is to “both shave off the accretion of traditional and confining conceptions of Mormon art and expand our imagination of its power and potential to shape identity, experience, and community with others, as well as the divine” (15). Latter-day Saint Art operates as a successful catalyst and will continue to prove its worth as new scholarship emerges in response—which the editors “welcome and encourage” (9). Whether it be through critical rebuttals to the individual author contributions or the occurrence of new questions born out of their findings, this volume will prompt additional research, study, and insights into the field of Latter-day Saint art for those that work within and adjacent to it.

However, the project’s interdisciplinarity (which this reader will always view as a strength), also opens itself up to the risk of unevenness and incoherence.

Some contributions in Latter-day Saint Art—like Colleen McDannell’s careful tracing of the shift in temple art over the last two decades, Glen Nelson’s uncovering of the influence of the Art Students League of New York on Latter-day Saint artists, and Analisa Coats Sato’s extrapolation of the unique parameters within which faculty and students of the BYU Art Department work—are stronger than others and best exemplify the editor’s overarching objectives. Other chapters, like Mary Campbell’s photo historic unpacking of Brigham Young’s Big Ten or Rebecca Janzen’s essay on Mexican-Mormon architecture, are of narrower interest, most meaningful to those working within a specific subset of scholarship.

In terms of clarity, the book does not progress chronologically. Rather, the chapters are grouped loosely by category without the help of formal dividing sections. Authors are placed in dialogue with one another around unifying themes, such as art as theology, image-making, politics of space, institutions and identity, exhibition and display—which are only outlined in the introductory essay. This choice was likely made to honor the complexity of the author’s arguments, methodologies, and topics while maintaining a seamless dialogical transition between the chapters. Still, without these breaks built into the structure of the book, it is up to the readers to discover this logic in the introductory essay or decipher it intuitively.

All this is to say that the interdisciplinary nature of the volume, though largely effective given the project’s aims, comes with a few trade-offs. The book does not pretend (or want) to be an exclusively devotional or art historical or historical or religious or cultural—or whatever!—work of scholarship. For this reason, it may not maintain consistent audience appeal from chapter to chapter and risks irking those in need of a little more organization.

This is not a book for those seeking a singular definition of Latter-day Saint Art. Beardsley, Allred, and their community of contributors aim to offer a “variety of approaches and artworks,” giving “substance and detailed vitality to the beautiful and multidimensional answer to the always inadequate question of singularly defining what Mormon art is” (15). It seems appropriate, then, that Terryl Givens, author of People of Paradox (2007), was tasked with the inaugural chapter. Consistent with previous publications, Givens writes in Latter-day Saint Art about the various theological, systemic, and cultural paradoxes of Mormonism: the tension between individual salvation and communal exaltation, the belief in continuing revelation and an open canon without recent additions to Latter-day Saint scripture, the conflation of sacred and recreational space from pulpit to basketball court in Latter-day Saint chapels, to name a few. Though these oppositional ideologies and features of the faith exist in tension, for Givens they are not necessarily at odds. “These paradoxes,” he writes, “are destabilizing in the best of ways, providing the catalyst, the energy, for perpetual self-examination and healthy discontent” (18).

Not only does Givens demonstrate the practical “how” of the editors’ theoretical “why” as outlined in the introduction, he simultaneously lays the foundation for the authors that follow. The volume itself lives in paradoxical tension with its desire to create room for nuance and complexity, while necessarily limiting its scope. Readers who resist adopting Givens mindset, (or put simply by others as a “both things are true” approach), may find themselves frustrated, unable to fully appreciate the diversity of perspectives and multiplicity of definitions it puts forth.1 For those seeking a singular definition of Latter-day Saint Art, this is not the book for you.

Instead, Latter-day Saint Art’s multidimensional both/and approach will be legible to the reader who is familiar with or knows little to nothing about Mormonism. Latter-day Saint Art will be most helpful to academics, but its value extends to those outside traditional intellectual contexts. Professors’ syllabi will benefit from the inclusion of individual chapters best suited to their courses, while independent scholars interested in religion, art, and cultural theory can gain further insight into their respective fields as they are exposed to uniquely Latter-day Saint paradigms. This book will be an invaluable resource to any reader wanting to understand the complex relationships between personal faith, systematized belief, religious institutions, and cultural production. Mormon readers especially, of any degree of commitment or affiliation, will learn something about themselves as they witness each author navigate the push for assimilation and the pull of peculiarity that has characterized the Latter-day Saint experience for over 200 years.

The volume is also full of admirable attempts to be more international, diverse, and equitable in its topical scope and authorial representation. Further study of Latter-day Saints and their cultural products will require much more of this, due to the Church’s increasingly global member population and influence. While it is impossible to fully escape the US-centric nature of Mormonism in its origination, this volume opens the door to international artists, subjects, and regionally specific phenomena within Latter-day Saint identity—and will hopefully prompt support of international scholars who are best positioned to speak on such topics.

Unlike most publications, this book does not end with a summary of answers but instead puts forth a series of open-ended questions. Rather than cyclically reinforce any one argument in its conclusion, this volume—very deliberately—does not end where it begins. It effectively reviews what has come before, explains how and why we are where we are, and uses its own momentum to propel us forward into uncharted territory. In her incisive afterword, Laura Allred Hurtado marks a definitive turn in the discourse. She writes:

“If I were asked to define Mormon art—a philosophical question I’ve grown tired of and that has taken up so much of the discourse as to become distracting—not only would I struggle to answer, but I would likely wonder whether the question itself is worth asking, because of the circular and limiting nature of the inquiry itself” (627).

Without discrediting the thoughtful and brilliant contributions of the collected authors, Allred Hurtado expertly weaves together common threads, distills central arguments, communicates the stakes, and launches us into a new era of scholarship. Like a musical elision, her essay could be both the end of this book and the beginning of the next, marking a methodological shift and ceremoniously breaking new ground.

Thanks to Latter-day Saint Art—and much to the relief of authors like Allred Hurtado—we can finally stop asking the question, “What is (or isn’t) Mormon art?” The triumph of this volume is threefold: it puts to rest our preoccupation with a singular definition of Mormon art thus expanding the criteria for canonic inclusion, provides alternative frameworks with which future scholars can proceed, and urges readers to consider all that Latter-day Saint art already is and can be.

The study of Latter-day Saint art will never be the same.

This essay also appears in a forthcoming issue of BYU Studies.

Maddie Blonquist is the Roy & Carol Christensen Curator of Religious Art at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art. In 2018, she graduated from Brigham Young University with degrees in Music and Interdisciplinary Humanities and went on to receive an M.A.R. in Visual Arts and Material Culture from Yale Divinity School.

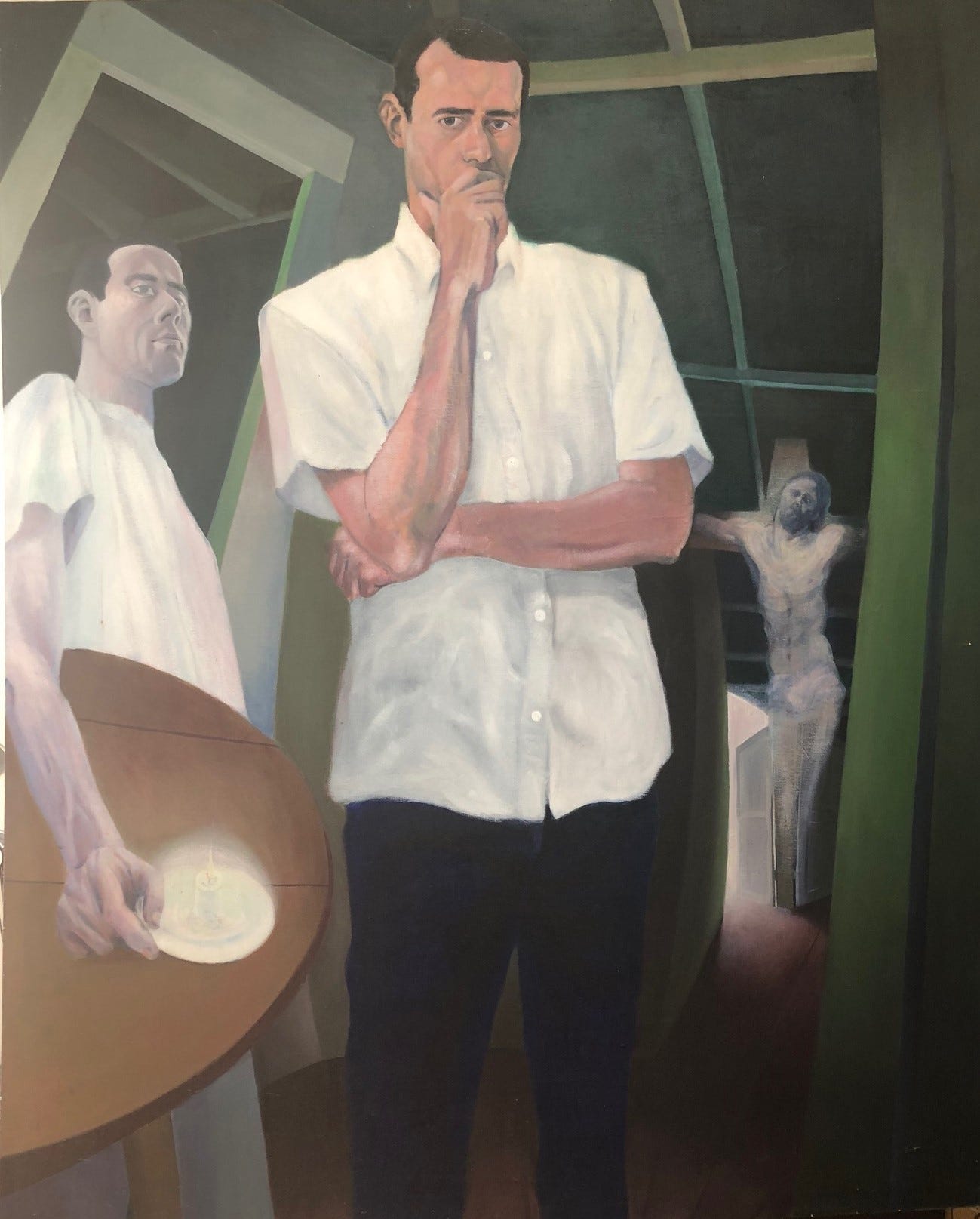

Art by Gary Ernest Smith, C.C.A. Christensen, Casey Jex Smith, Madeline Rupard, Rose Datoc Dall, Ron Richmond, and Kwani Povi Winder. All works featured in Latter-Day Saint Art: A Critical Reader.

Gary Ernest Smith, Decision (1968). Springville Museum of Art.

C.C.A. Christensen, Handcart Pioneers’ First View of the Salt Lake Valley (1890). Springville Museum of Art.

Casey Jex Smith, The Seer Stone (2016). Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Church History Museum.

Madeline Rupard, Drew and Michele in Costco (2017).

Rose Datoc Dall, Worlds Without Number (2020).

Ron Richmond, Water with Descent (2016). Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Church Museum of History and Art.

Kwani Povi Winder, My Prayer (2018). Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Church History Museum.