For many years I taught law enforcement officers in a seminar for those in the upper administrative ranks—a liberal arts-based approach to “executive leadership training.” My module was called “religion and leadership,” and I employed texts from a variety of religious traditions for insight into the ethics of management, leadership, and human relationships generally. One text I assigned was Doctrine and Covenants 121:39: “We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.”

My approach to this text was actually to call into question, not the exercise of authority—but its de facto intrusion into the scheme of human relationality. The omnipresent potential for abuse of which the scripture warns presupposes a kind of fragility that has been introduced into the world by the mere presence of authority. One can turn a screwdriver or a milk jug into an instrument of violence—but they don’t come with warning labels because their presence in the world doesn’t indicate an innate disruption of the natural order; they do not inherently destabilize human relationships and reconstitute them in artificial ways.

In law enforcement, this dislodgement of the natural inevitably and universally takes place in ways both subtle and emphatic, and I would encourage the officers to recognize these facts. A patrolman stops a motorist. In approaching the car, the officer is standing, the motorist seated; the officer looks down, the motorist up; the hat exaggerates the differential. The uniform speaks of authority; the badge betokens power; the holstered gun its visible guarantor. Before the officer has spoken a word, two human beings created equal are reconstituted into a radically imbalanced power differential. Do you not sense, I would ask them, something wrong, something askew, something unnatural and unsettling in that human interaction, however polite and uneventful the interaction?

I support law enforcement, and am glad police officers are present to protect and safeguard citizens. I believe I made that clear to those in the seminar, and they did not see my point as a criticism of them or the system. It was, rather, an attempt to illustrate the costs of authoritative systems, however legitimate. But I was also trying to provoke reflection on a larger point, perhaps too philosophical or theological for a secular leadership training seminar, and that is this: are all intrusions of hierarchy into human community an evil, however crucial for larger purposes, however necessary in the lived context? Is this, perhaps, what the Lord is telling us two verses later (a passage not assigned to my students): “No power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood.” That is an intriguingly absolutist claim. It doesn’t tell us priesthood power has to be righteously exercised: rather, “No power” can be “maintained” by the priesthood. Period. What does this mean, given that we clearly believe in a church invested with divine authority, presided over by legitimate priesthood leaders? Or that we reverence a God who presides in the heavens, and a Lord who is head of his church?

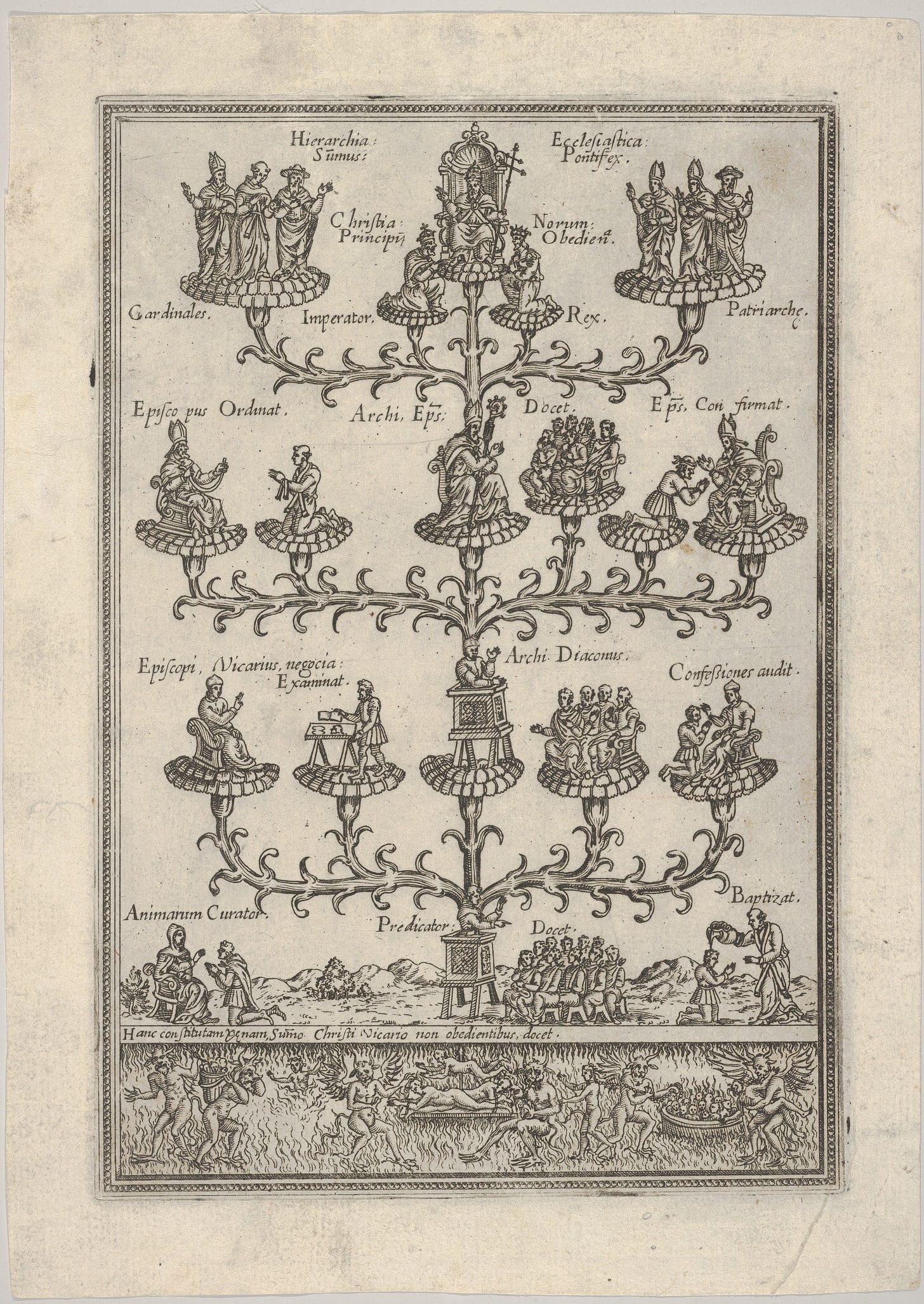

I wonder sometimes if Christianity had been established in the year 1980 or 2020, what our religious language would look like. Would we think of God as the CEO rather than King? Would we seek to be faithful employees rather than servants? Would Christ be our angel investor rather than redeemer, and the atonement theologized by analogy with overextended credit and derivatives rather than offended honor and ransomed souls? I do not mean these questions to be as facetious as they sound, for my examples are meant to highlight the extent to which Christian theology appropriated the political and economic models prevalent in that ancient world to make sense of eternal things. And no fact of life was more dominant in the ancient world than social hierarchy. The Great Chain of Being assigned to every individual a rank and status, an identity that was understood almost entirely as a function of whom you were above and whom you were below.

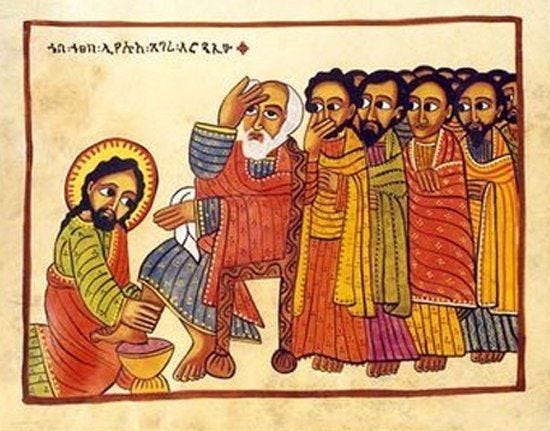

We can read and ponder, but we cannot replicate the shock of that moment when Jesus divested himself of his garments, and wrapped in a meager towel, washed the dirty feet of that stunned and scraggly group of faithful followers. With the hindsight of two millennia, we might turn fresh eyes to those words: “no power or influence can or ought to be maintained by virtue of the priesthood.” Even the Son of God, as he demonstrated then and would demonstrate again on the cross, willed to “draw all men” to himself. What power the Gods possess, they exercise by virtue of love.

To receive each new Terryl Givens Wayfare essay by email, first subscribe and then click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."