On Bruce R. McConkie

Much of what we think about Bruce R. McConkie today is wrong.

In 2005, the University of Utah Press issued David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, written by Gregory Prince and Robert Wright. It is a crucial contribution to the study of Latter-day Saint history. But I find it striking that, over the nearly two decades of the book’s circulation, I’ve seen and heard one anecdote from it cited far more often than any other. It’s about Bruce R. McConkie and what Prince and Wright call “the controversy over Mormon Doctrine.”

Today, the anecdote is perhaps so well known that it doesn’t need repeating, but here’s a refresher, taken straight from the biography:

[President] McKay’s initial reaction to [Mormon Doctrine, originally published in 1958] was not favorable. He summoned two senior apostles, Mark E. Petersen and Marion G. Romney [and] asked them if they would together go over Elder Bruce R. McConkie’s book. Petersen and Romney took ten months to critique the book and make their report to the First Presidency. Romney submitted a lengthy letter on January 7, 1960, [and] Petersen gave McKay an oral report in which he recommended 1,067 corrections that “affected most of the 776 pages of the book.” The following day, McKay and his counselors made their decision. The book “must not be republished, as it is full of errors and misstatements.”

As interesting as this story is in its own right, I find myself far more interested in why Latter-day Saint intellectuals have been so taken by it.

There is, of course, the obvious reason. The sheer influence of Mormon Doctrine within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from the time of its publication to the end of the twentieth century can hardly be overstated. It was so often treated among the Saints as the final court of appeals on what constitutes the official doctrine of the Church (consider its ubiquity in the form of quotations throughout Church-published materials until the early 2000s) that the story of its rocky beginnings naturally registered to many as a marvel. And because so many academically inclined Latter-day Saints had their own doubts and suspicions about many claims made and many conclusions drawn in Mormon Doctrine, they could welcome news that the President of the Church at the time of its publication was, effectively, on their side.

Vindication, in a word. Hopefully without a spirit of vindictiveness.

But vindication, I think, isn’t enough of an explanation. The fact is that Bruce R. McConkie and Mormon Doctrine have been treated unfairly, in many regards. There’s more to what both the man and his work represented for the historical development of the Latter-day Saint faith than is generally allowed. This is not to say that anyone should feel bound to agree with any particular claims or conclusions in a book like Mormon Doctrine. It’s certainly not to excuse certain deeply problematic things said in that work or elsewhere (about race especially). It’s rather to say that there’s too much of the boogeyman in the common portrait that Latter-day Saint intellectuals paint of McConkie.

It’s time for a reassessment. And that means that it’s time for a little context.

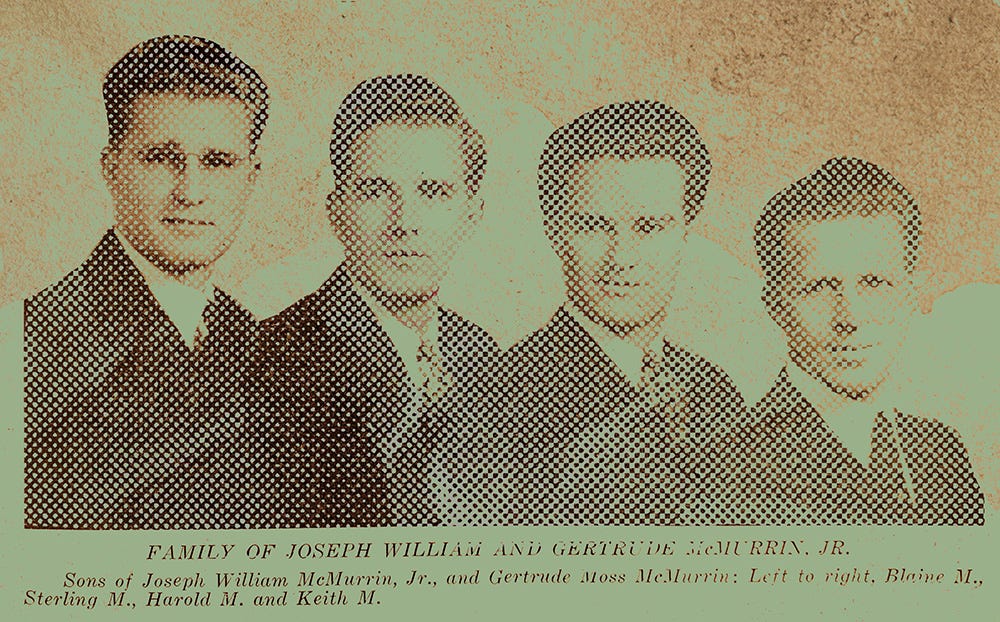

In 1965, the University of Utah Press issued philosopher Sterling McMurrin’s book The Theological Foundations of the Mormon Religion. It remains important despite its age, at the very least because there exist so few scholarly attempts to draw together the whole of Latter-day Saint thought. But probably more important for the lasting significance of McMurrin’s book is the timing of its original publication. The appearance of Theological Foundations was exactly contemporary with the formal organization of the Mormon History Association, with the towering historian Leonard Arrington as its first president. Arrington’s leadership of what would soon be called “the New Mormon History” would prove to be of immense and lasting cultural importance.

In 1965, it seems, the question was whether theology or history marked the way forward for Latter-day Saint intellectuals. And as of 1965, the question was still undecided. Arrington and McMurrin, the historian and the philosopher, were contemporaries with a similar sense of the obstacle that then faced Latter-day Saint intellectual culture. They nonetheless had almost entirely opposite ideas about how to tackle that obstacle.

McMurrin made clear at the end of Theological Foundations what he took to be the obstacle for Latter-day Saint intellectuals. He concluded the volume with a few reflections “on the task of Mormon theology.” “Yesterday,” he wrote, Latter-day Saint theology “was vigorous, prophetic, and creative; today it is timid and academic and prefers scholastic rationalization to the adventure of ideas.” What had crept into Latter-day Saint intellectual culture? McMurrin pointed above all to “the impact of religious and social conservatism” and to “the seductions of irrationalism.” As Theological Foundations and other writings by McMurrin make perfectly clear, he worried that the Saints had followed in their own way a larger Christian trend in the mid-twentieth century—that of neo-orthodoxy. That is, representatives of the tradition were talking more of divine grace and less of human potential, emphasizing the limits of human rationality and declaring that divine revelation is transparent and incontestable. McMurrin found all this philosophically and theologically disappointing.

It’s perfectly clear whose passing McMurrin lamented: James E. Talmage, John A. Widtsoe, and especially B. H. Roberts—the great Progressive Era thinkers who outlined the possibility that Joseph Smith’s teachings embodied an optimistic humanism. It’s also perfectly clear whose rise McMurrin found discouraging. There were two figures who represented the new Latter-day Saint theology. First, there was the erudite historian of antiquity whom McMurrin regarded as “the strangest aberration that has ever afflicted Mormonism”: Hugh Nibley. In McMurrin’s view, though, Nibley wasn’t a theologian; he was a historian. But, in McMurrin’s view, Nibley did little more than labor to arrange historical data to bolster the new theology. Nibley, in short, wasn’t the architect of the new theology but a builder of walls around it.

Who, then, was hard at work within the walls of that new theology itself? Without a doubt, for McMurrin, it was Bruce R. McConkie. It was McConkie’s thought that he regarded as “timid and academic,” preferring “scholastic rationalization to the adventure of ideas.” Nibley enjoyed the life of the mind, but McMurrin believed he was putting all of his best intellectual efforts in the service of defending a theological vision that was antagonistic toward the life of the mind.

The case can be made that it was the same cultural development—the rise of Bruce R. McConkie—that motivated the New Mormon History led by Leonard Arrington. Especially telling is what Jan Shipps once said was “the mantra of the LDS intellectual community” during the formative years of the New Mormon History: “Mormonism does not have a theology; it has a history.” The idea, it seems, was that doctrinal elaboration and theological systematizing rightly found their places in other forms of Christianity. Latter-day Saints, the historians claimed, sacralized its past rather than any system of thought—such that, if there was something that might be called a Latter-day Saint theology, it simply was the Church’s history. At any rate, it was apparently clear to someone coming from the outside (Shipps was not a Latter-day Saint) that the historical project was in large part driven by a felt need to stop the flow of Latter-day Saint theology. It was perhaps viewed as commendable that there had been robust Latter-day Saint theological activity in the past, but it was apparently felt that such previous work should be treated as an archive for historical reflection rather than a resource for further theological speculation.

Why such antipathy in the mid-1960s toward the very idea that the Saints might “have a theology”? The most obvious answer by far is simply that Bruce R. McConkie’s writings left Latter-day Saint intellectuals with little hope for the theological enterprise as such. Given Elder McConkie’s strongly authoritarian streak, it was safer by far for scholars to settle their minds in intellectual territories where his flag wasn’t flying. Moreover, historians might well have reasoned, if one could slowly convince others (and even the institutional Church!) that “Mormonism does not have a theology; it has a history,” then the influence of a book like Mormon Doctrine could be trusted to fade in time. In the meantime, intellectually inclined Latter-day Saints had plenty of room to do interesting work without doing theology.

In retrospect, then, McMurrin and Arrington might be viewed as having seen the challenge to Latter-day Saint intellectual life in 1965 in similar ways. They developed strikingly different strategies for moving forward, however. The historians, in essence, wagered that the passing of the early twentieth-century theological vision was lamentable but irreversible, and so the task for Latter-day Saint intellectuals was now to historicize what had passed. McMurrin, by contrast, wagered that there might be enough life in the Latter-day Saint intellectual community to revive the passing theological project and so to mobilize it against what he saw rising. Either way, it seems, both parties believed that what was needed above all was an alternative to Bruce R. McConkie.

Who was Bruce R. McConkie? It’s perhaps worth providing just a sketch of this towering figure, especially because collective memory of him has begun to fade.

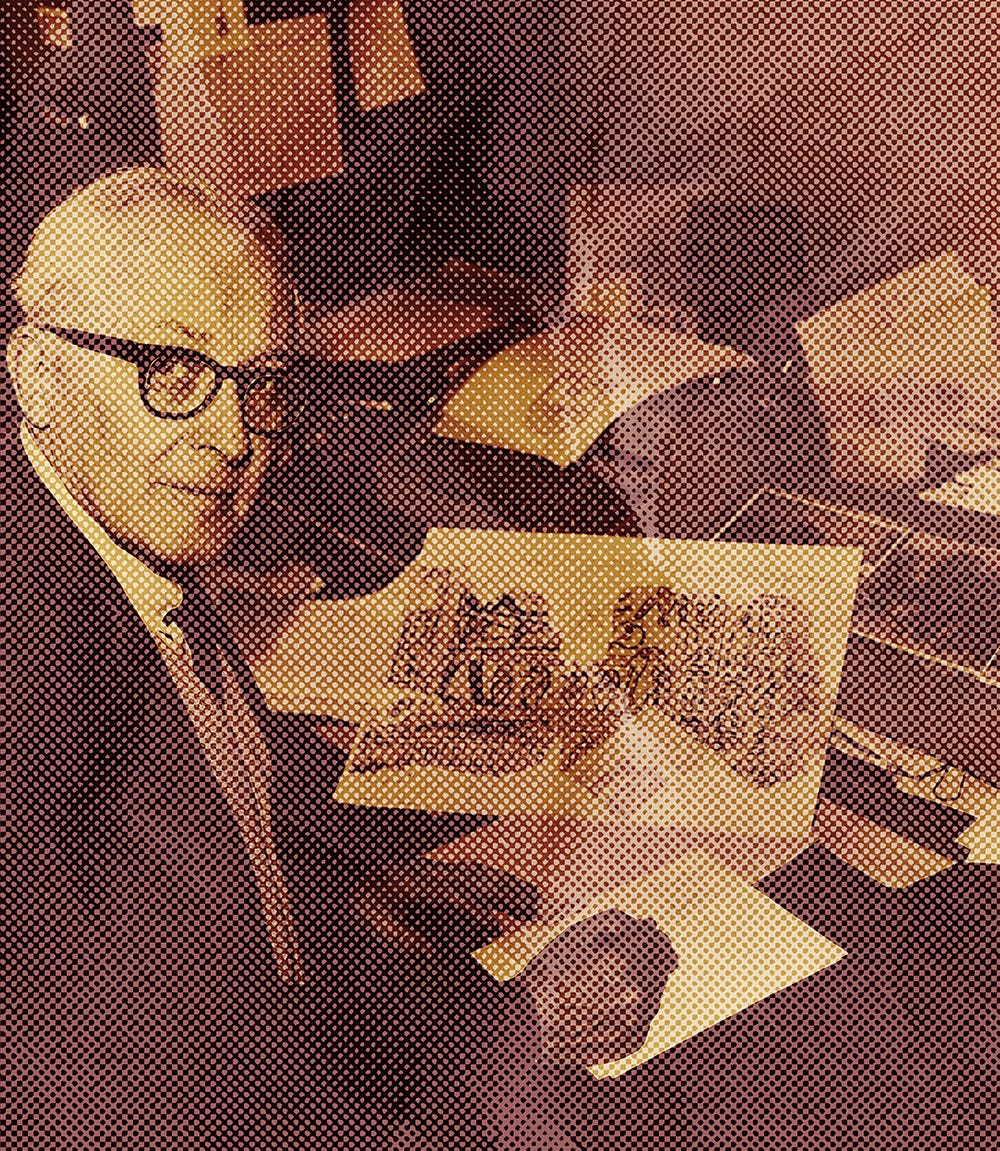

Eventually, McConkie came to be known as an astonishingly bright but unmistakably authoritarian Latter-day Saint leader. He began, though, as an aspiring young professional (in law and business). But just into his adulthood, he married the daughter of then-Apostle (and later Church President) Joseph Fielding Smith (who in turn was the grandnephew of founding prophet Joseph Smith). Following his father-in-law’s intellectual footsteps while he pursued his professional training, the young man soaked up writings by American Evangelicals and other conservative Christians who contended against modernizing trends and developed an intense interest in doctrine. He himself would eventually define doctrine as “the tenets, teachings, and true theories found in the scriptures; . . . the principles, precepts, and revealed philosophies of pure religion; [and] prophetic dogmas, maxims, and views.” Its exposition and systematization became his life’s passion.

Bruce McConkie became Elder McConkie in 1946, moving into general Church leadership (as what is now called a President of the Seventy) in his early thirties. Beyond his ecclesiastical duties, he gave the decade of the 1950s to compiling Fielding Smith’s teachings into a three-volume compendium, as well as penning his own influential theological encyclopedia of sorts, the already-mentioned monolithic Mormon Doctrine, which appeared in 1958. He then spent the 1960s writing a three-volume doctrinal commentary on the New Testament, the last volume of which appeared in 1972—the year he became an Apostle. Elder McConkie gave his final years (he died in 1985) to writing doctrinal treatises on Latter-day Saint Christology, as well as what he called A New Witness for the Articles of Faith. His final public testimony, offered in general conference shortly before his death, has often been praised as a classic of Latter-day Saint devotional oratory.

It’s hard to overstate Elder McConkie’s influence on Latter-day Saint culture and thought in the second half of the twentieth century—despite the labors of the New Mormon History to create an intellectual alternative to his thinking. This is especially true because he absorbed into himself the already enormous cultural and intellectual authority of his father-in-law (first and most influentially by serving as editor for the three-volume collection of his father-in-law’s teachings). A lawyer by training but a theologian by disposition, McConkie wedded the rigor of courtroom argumentation to a commonsense approach to the meaning of Latter-day Saint scripture. The result was a layman’s rationalism: profound trust in the capacities of the mind, so long as that mind was bridled by unswerving loyalty to the Church. Beginning with Mormon Doctrine, McConkie essentially labored at producing a Latter-day Saint theological system that naturally appealed to conservatively minded believers who nonetheless had strong intellectual inclinations.

What this meant, above all, was that his writings came like manna from heaven to teachers in (what was then called) the Division of Religion at Brigham Young University and in the Church’s seminaries and institutes of religion. In search of something more than manuals to satisfy their curious minds but unsure about the boundless expanse of academic research, they found in McConkie what they most wished for. For decades, the vast majority of the Church’s active younger members, especially in the United States, went through these programs and so were shaped by a heavy dose of McConkie-inspired instruction. Thus, by the 1970s and continuing to the end of the 1990s, whatever McConkie called “Mormon doctrine” basically was Mormon doctrine, its dissemination subsidized by the Church (eventually in a formal manner: quoted liberally throughout Church publications).

In 1965, though, McConkie’s project was still young. His first book, Mormon Doctrine, was only seven years old, and his second (the first volume of the Doctrinal New Testament Commentary) appeared just that year. McConkie wouldn’t become an Apostle until seven years later. It was clear that what McConkie was spearheading would end up having real cultural force, but its fortunes weren’t entirely clear yet. All that was apparently clear to both the historians working under Arrington and the lone-voice philosopher McMurrin was that something else needed to be on offer.

The year 1965 now sounds like a long time ago. What has happened since?

There’s a relatively standard way of recounting the years since 1965. McMurrin ended up busy with other things, despite his plea for new work in Latter-day Saint theology. Here and there a work of theology in a style more recognizably academic than McConkie’s would appear, but these were unrepresentative of the “vigorous” thinking McMurrin saw himself as calling for. Theology disappeared or went underground for a time. Meanwhile, the historians went on to striking success, their influence waxing in the 1960s and ’70s, waning in the turbulent 1980s and early ’90s (when, curiously, certain theological debates plagued the historical conversation), but then exploding in the new millennium. Only when historical work broadened into the discipline of Mormon studies early in the twenty-first century did it begin to appear that there might be space again for theology’s possibilities as McMurrin once envisioned them. Works on Latter-day Saint theology suddenly began to appear, and then to proliferate, and the theologically inclined began to professionalize.

Theology, it would seem, was rather suddenly back after a long hiatus. It took nearly half a century, but McMurrin’s call could finally be answered afresh in the early twenty-first century—if for no other reason than that the influence of Bruce R. McConkie began to fade after the eventual successes of the historians. And the new wave of Latter-day Saint theologians swelling in the first decade of the twenty-first century—led, in so many ways, by Blake Ostler—often laid claim to the same early twentieth-century thinkers that McMurrin had summarized and celebrated in his 1965 book: Talmage, Widtsoe, and Roberts. Had McMurrin lived just a little longer, he might have been cheered to see his vision realized at last.

This, as I say, is the usual way of telling the story of the past six decades. And it may be that this way of telling the story will prevail. After all, Latter-day Saints are familiar with stories of falling away and restoration, so perhaps such a telling feels natural. But there’s a subset of Latter-day Saint theologians working in the first quarter of the twenty-first century that, I think, this story doesn’t account for. Thinkers of this other sort include James Faulconer, Rosalynde Welch, Adam Miller, Kimberly Matheson, and others. (I count myself among them.) Such thinkers have apparently found McMurrin’s account of Latter-day Saint theology largely unhelpful, have mostly ignored Talmage and Widtsoe and Roberts, have been somewhat puzzled by the intellectual styles of many contemporary Latter-day Saint thinkers (despite having deep respect for them), and have wondered why so little work in contemporary Latter-day Saint theology focuses on the concrete realities of lived faith. Perhaps above all, such thinkers have wondered about the at-best occasional role played by scripture in so much of Latter-day Saint thought today. These other theologians’ points of orientation have lain elsewhere, and their methods of proceeding have been otherwise, than those of their contemporaries.

Where did they—or, really, we—come from? I shouldn’t speak for others, but I will venture a hypothesis. We other theologians are the continuation—albeit with certain obvious reservations—of the intellectual project launched by Bruce R. McConkie. We were, I wager, shaped intellectually and devotionally far more by the concerns and interests of the Church Educational System than by any strong sense of resistance to it. To be sure, we share few of McConkie’s particular conclusions, but we do share something like the same animating spirit. Yes, our methods have been shaped by our own professional training (generally in and around the so-called “continental” style of philosophy) rather than by the legal profession, but we tend to think that McConkie was right to bring all the rigor he could to the life of faith. An especially important difference is that McConkie consistently claimed to speak for the Church, while we only offer our work to the Church in the hopes that it’s useful—but this means that we, like McConkie, see our thinking as being in the service of the Restoration more than of the academy.

And, above all, there’s scripture. It has far too seldom been noted that McConkie, whatever else one wishes to say about him, more or less singlehandedly convinced two or three generations of Latter-day Saints that their faith had to be worked out through an unswervingly dedicated study of the unique set of scriptural books embraced by the Saints. Remember that he wrote a three-volume doctrinal—that is, theological—commentary on the New Testament. That a Latter-day Saint thinker ventured to do such a thing more than fifty years ago boggles the mind, really. Something like McConkie’s conviction regarding the import of scripture has, above all, guided our—or, at the very least, my—work as a theologian.

Why make scripture a hard foundation for the future of Latter-day Saint thought? Should Latter-day Saint thinkers feel so beholden to texts that come from increasingly distant historical periods, increasingly foreign worlds? For my money, yes, and for a host of reasons. I’ll name just three for the moment.

First, Latter-day Saint scripture is almost certain to have more sticking power than anything else current today within the Latter-day Saint context. Whatever the future of this particular religious tradition looks like, there’s almost certain to be periodic returns to, say, the Book of Mormon. Second, scripture is something that sits in the hands of every member of the Church, such that reflection beginning from these texts is most likely to matter to those trying to work out their relationship to God. If theology is to make a difference to anyone beyond the walls of the academy, scripture is likely to be the vehicle that carries it there. Third, scripture, if it’s read carefully and consistently, refuses to allow the academically inclined to reduce it to mere systems of abstract concepts. Scripture is messy and complicated, its increasing historical distance illustrative of such complexity—and honesty in reading it can only help prevent the theological endeavor from flattening faith into something foreign to real life.

Are there challenges? No doubt. The study of Latter-day Saint scripture is still young. What scholarship exists that might be useful to theological readers has been driven not only by historical but by historicist tendencies, resulting in too many ventures that have been overly sure of their hypotheses and given to reductionist interpretations as a result. Further, many texts in the canon leave readers with troubling ethical concerns that need addressing in responsible ways. Further still, very little academic support exists at present to harbor the serious study of Latter-day Saint scripture—whether for theological purposes or otherwise—and so the incentives are few for drawing real expertise to the task of interpretation. There are, in short, any number of hurdles to clear. It’s worth the effort to clear them, however, to give Latter-day Saint theology a center of gravity, so that it’s far less prone to be “carried about with every wind of doctrine” (Ephesians 4:14).

Not long after the historians took the stage in the 1960s, they began to speak of a “lost generation” of historians—historians like Juanita Brooks and Dale Morgan who wrote in the 1930s and ’40s and made major contributions that, because they were ahead of their time, too easily went unnoticed. I think it’s time to recognize another lost generation, a lost generation of theologians. Bruce R. McConkie deserves reinvestigation. Latter-day Saint scholars haven’t yet asked why he did what he did, how he went about it, and with what intellectual effects. It’s time to do so. What did he—and those who worked in his wake for two or three decades—contribute to Latter-day Saint thought, and in what ways does today’s theological work build on foundations laid by such surprising forebears?

Latter-day Saints have, from almost the very beginning, taken the redemption of their ancestors to be among their divinely appointed responsibilities. We scour census records, visit parish archives, learn how to use microfilm, and rifle through attic treasure chests—all in the hope of recovering the lives and the legacies of those who would otherwise fade from our collective memory. Shouldn’t we feel as bound to the thinkers and theologians of our own faith tradition’s past as we do to the similarly flawed but lovable people who have forged our individual families’ histories? Theological reading of scripture comes to the present out of the past, and sometimes from uncomfortable quarters. But Bruce R. McConkie shouldn’t be mummified and sealed away in a crypt, left for historians of the distant future to speculate about. We have something to learn from him right now—or something that we’ve already learned from him that’s alive right now.

The shape of future Latter-day Saint thought may depend on how honest we are about, and how faithful we are to, our theological past.

Joseph Spencer is a philosopher and an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Photo-illustrations by Esther H. Candari & Londan Duffin.