The night of Truth & Treason’s VIP pre-screening, I arrived to exactly the kind of buzz you come to expect before a big release. We struck our best red carpet poses at the step and repeat, nabbed our tickets, and settled into our seats. The Megaplex was in the heart of Utah County, and the theater whirred from the familiar exchanges of historians and foundations and tastemakers who frequent these events. We were all ready to post our hashtags and cheer.

However, sometime between the opening scene and the credits, we were transported. Or perhaps the room itself was transfigured. The standing ovation was reverent, like what you might expect to hear after a hymn if we applauded in our faith tradition. The theater had become a space of collective reckoning, perhaps even discomfort, calling back to the fervor of those youth firesides where you left knowing there were changes you needed to make. This was not sentimental filmmaking. It was spiritual in the most potent sense of the word, and the attempts to manufacture enthusiasm afterward fell flat in the face of what we had just witnessed. Genuine art holds up a mirror and refuses to let us look away. After the screening, a friend told me the film had fundamentally altered his perspective.

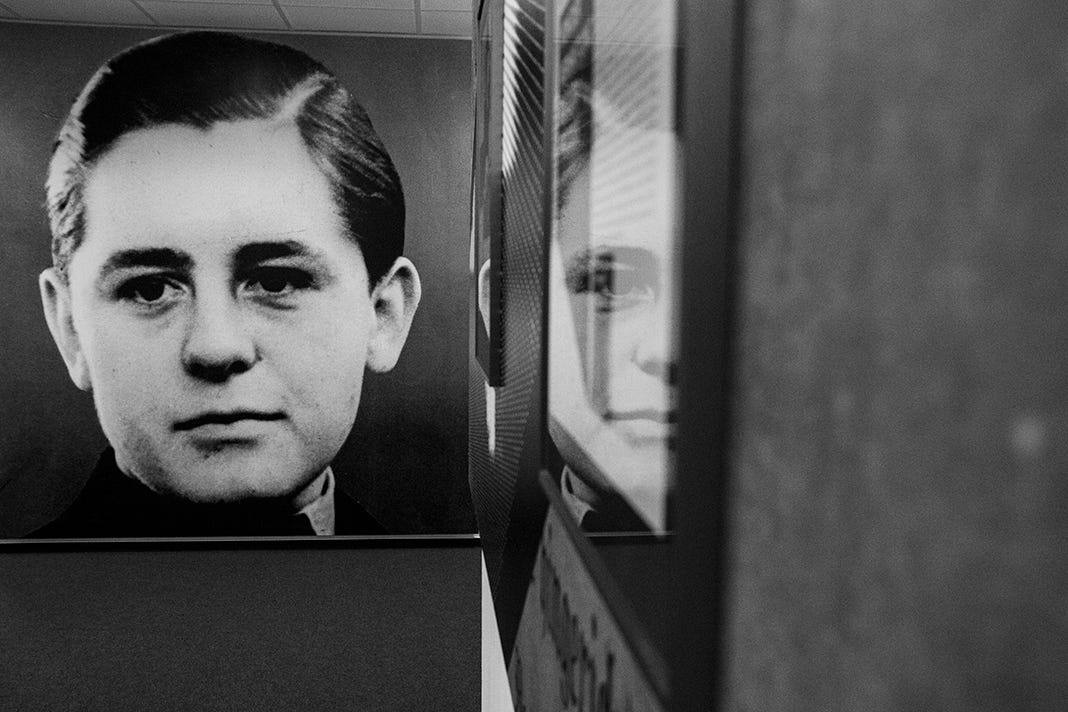

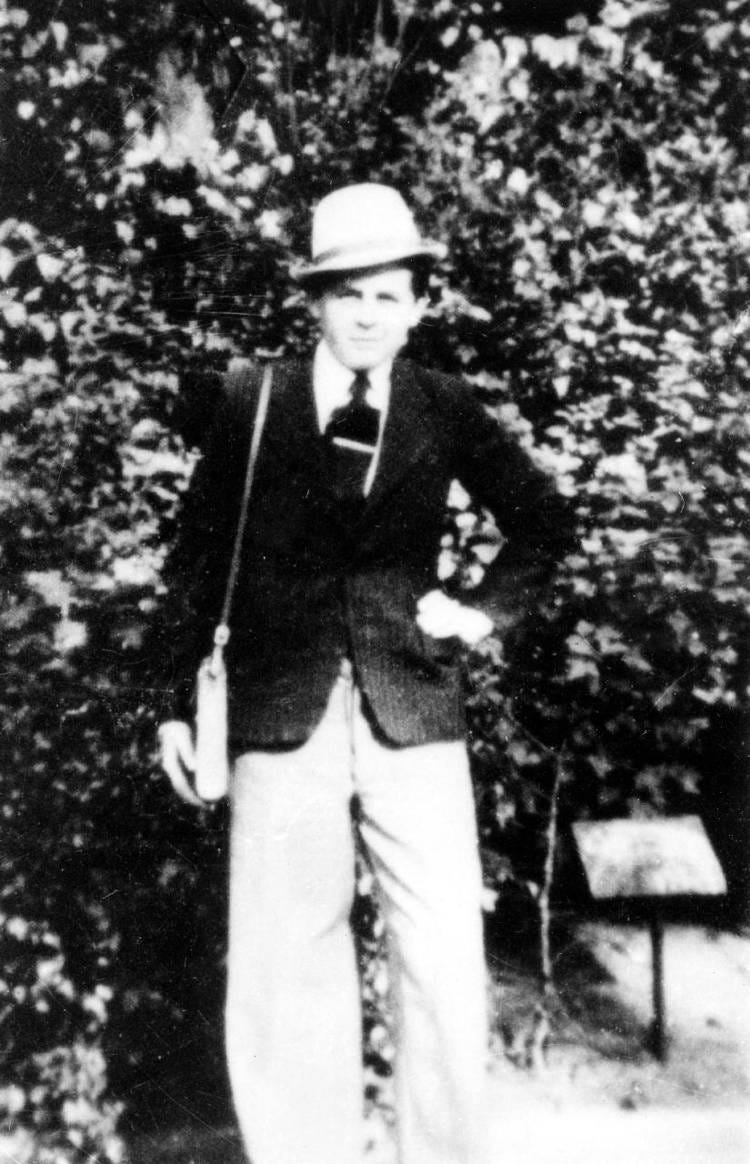

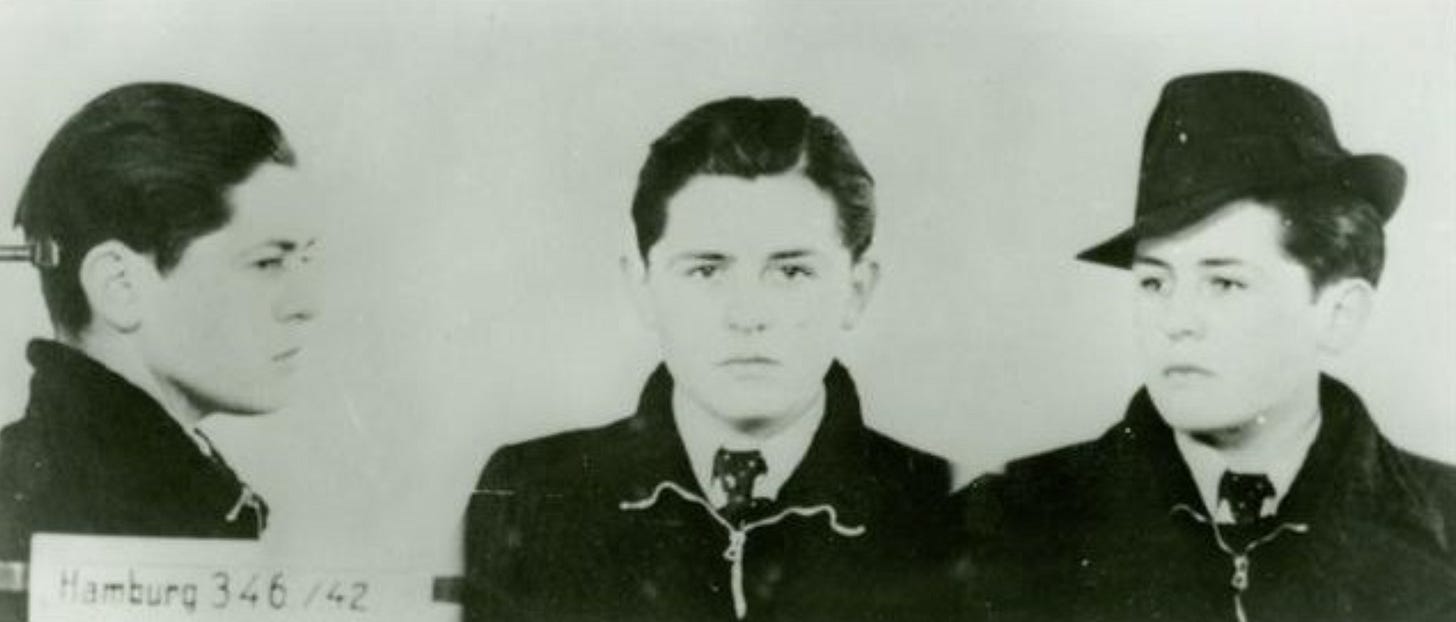

Matt Whitaker’s Truth & Treason tells the true story of Helmuth Hübener, a sixteen-year-old Latter-day Saint from Hamburg who, in 1941, discovered his brother’s shortwave radio and began listening to banned BBC broadcasts. What he heard contradicted everything the Nazi propaganda machine had told him about the war, about Germany’s enemies, about the future of the Reich. Armed with a borrowed typewriter and red notecards stolen from the banned-books archive at City Hall where he worked, Helmuth began writing and distributing anti-Nazi leaflets throughout Hamburg. He convinced his friends Karl-Heinz Schnibbe and Rudi Wobbe to help him, slipping pamphlets into mailboxes and onto windshields, each one ending with a simple instruction: “This is a chain letter. Pass it on.”

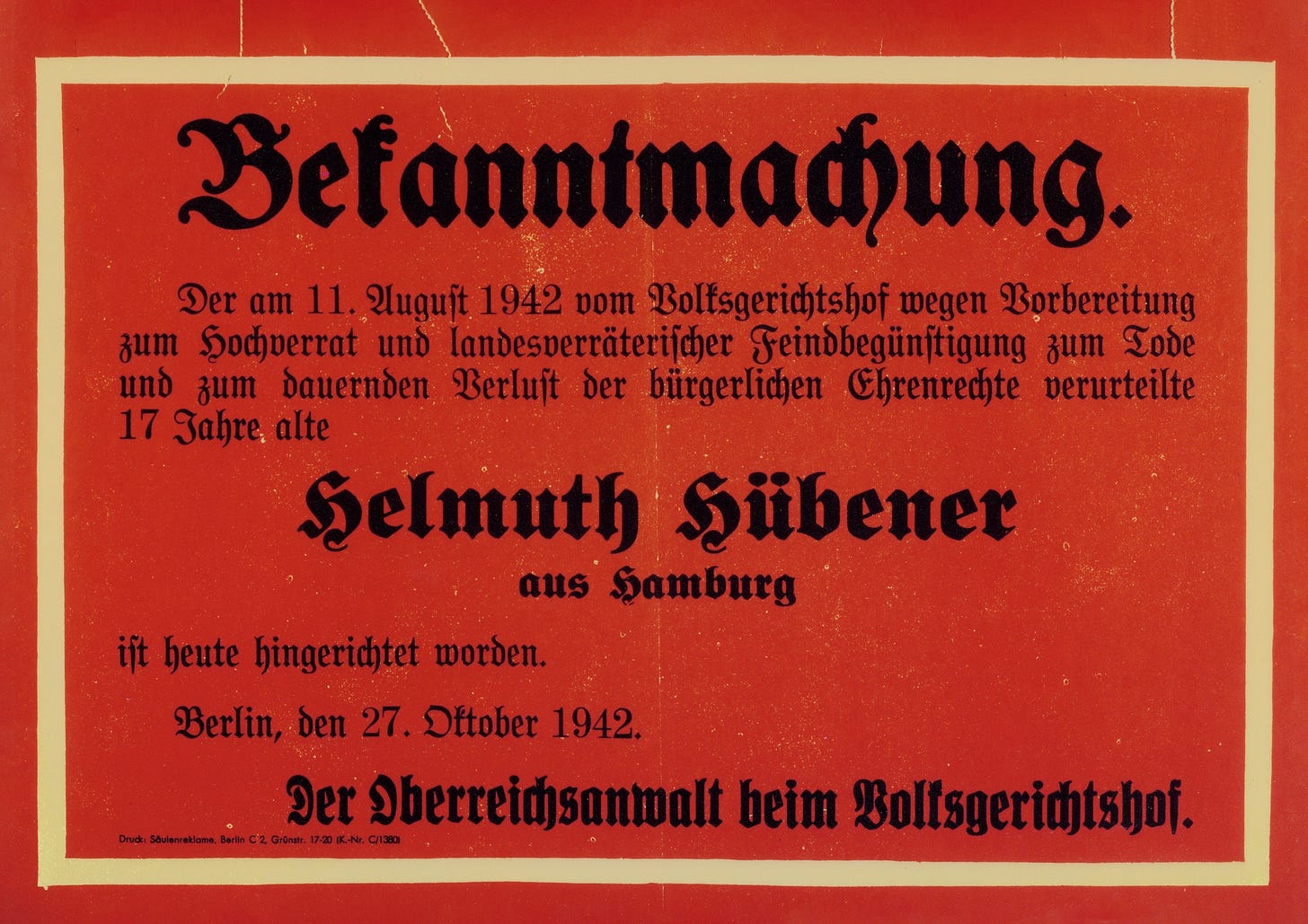

Over eight months, they distributed hundreds. By February 1942, the Gestapo had arrested all three. Helmuth, taking full responsibility, was tried in August and executed by guillotine on October 27, 1942 at only 17—the youngest person put to death for resistance to the Nazi regime.

Nazi resistance films constitute their own established genre. Among the countless that exist, many are well-known and award-winning, such as Schindler’s List, Defiance, Resistance—even The Sound of Music. Though willing to strip bare the unrelenting, uncensored horror of the Nazis, these stories sometimes risk romanticizing the act of defiance, showing us heroes who change the course of history, or at least save lives, making their sacrifices count in ways we can measure and applaud. Truth & Treason offers no such comfort. More conversant with Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life, which tells the story of Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter’s refusal to swear allegiance to Hitler, Whitaker’s film grapples with the emptiness that can accompany doing the right thing.

Like Hübener, Jägerstätter was executed for his convictions. Neither man’s resistance changed the outcome of the war. Neither saved Jewish lives in any measurable way. Neither toppled the regime or even slowed it down. And yet both films insist, quietly but firmly, that these men’s choices mattered profoundly—not because they altered history, but because their words stood as bedrock testaments to that which is axiomatically right, cleansing them from the blood and sins of their generation.

Where Malick’s film is contemplative and dreamlike, a three-hour meditation on faith and suffering that operates at the pace of prayer, Whitaker’s is far more accessible, more direct, perhaps slightly softer in its approach, while retaining a similar spiritual intensity. Truth & Treason isn’t perfect—more context for what really drives Helmuth would be welcome, and those answers may well exist in the expanded four-part limited series version. But it’s focused, and the real miracle is that it works at all, considering it was originally conceived as a series; that Whitaker managed to construct a coherent, emotionally satisfying feature from episodic material is a technical achievement that should not be underestimated. Each of these two films is about wrestling with what it costs to refuse complicity for one’s faith, even while condemned by fellow adherents of it. In this way these men are, perhaps, “as Job.”

It probably helped that Whitaker has been refining this story for two decades. In 2002, he directed Truth & Conviction, a documentary featuring interviews with Hübener’s surviving friend Karl-Heinz Schnibbe. The filmmaker literally looked up Schnibbe’s number in a Salt Lake City phone book and called him, beginning a relationship that would span years. Around 2008, with a feature screenplay for Truth & Treason by Whitaker and Ethan Vincent, Haley Joel Osment was cast as Helmuth Hübener and Max von Sydow as Judge Karl Engert. They even shot promotional footage with Osment as a proof of concept, but it never came to fruition. However, Whitaker never let go of the story.

The film begins with three boys standing up to a crowd of fellow Hitler Youth, and I think that’s important. We don’t hate these other kids just because they are Hitler Youth; so are our characters. Rather, we can observe how Hitler Youth is starting to affect them, or perhaps what kinds of beliefs and behavior benefit most from within it. Helmuth and his friends Karl-Heinz and Rudi are all Latter-day Saints, and like all young men of the church at that time, had been Boy Scouts until that was banned by the Nazis. Now they wear the same brown shirts as the bullies. They’re all German, all teenagers, all supposedly on the same side. What separates them is conviction.

Ewan Horrocks plays Helmuth with controlled restraint—not the passionate rebel of other resistance films, but a boy who becomes increasingly unable to stay quiet. He’s brilliant, working at City Hall as the youngest intern they’ve ever hired. And he’s excellent at writing propaganda for the Nazi machine. He likely would have done very well for himself simply staying in that lane, maintaining the pride of his parents and gaining admiration from his patriotic bishop.

However, one morning Helmuth’s Jewish-Mormon friend Salomon Schwarz is turned away from church, and together they watch their bishop post a sign at the door: “Jews Forbidden to Enter.” Shortly after, Salomon is taken away by the secret police. As forbidden BBC broadcasts continue to reveal the Reich’s lies, Helmuth realizes silence makes him complicit. His faith provides a moral vocabulary independent of the state. After he begins distributing his leaflets, the Gestapo assigns SS officer Erwin Mussener to hunt down their author. As both reluctant admirer and relentless pursuer of his quarry, Mussener functions like the film’s Javer.

A lot could be written about Mussener, made so tragically human by Rupert Evans as the loving father who does terrible things, and who suffers alongside other Germans as the war grinds on. The film recognizes that tyranny requires ordinary people to function, and that systems of oppression devour their own. But we’ve seen that story before. I’m sure it’s the Mormon in me, but the more interesting and challenging (albeit minor) character is Latter-day Saint Bishop and devout Nazi, Arthur Zander.

Daniel Betts plays Zander not as a bigot or an idiot, but as a decent, resolute man, who feels that his faith justifies his prudence. When Zander invokes the Twelfth Article of Faith to defend his sign—”We believe in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates, in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law”—he is not twisting scripture. Feeling the rumblings of an unstable nation thirsty for order, Zander assimilates in order to survive; he is the uber patriot, the model minority, all to demonstrate that he is a good, normal, moral, law-abiding, country-loving citizen. The character that embodies the most Latter-day Saint traits and values, save Helmuth Hübener, is Arthur Zander – the man who wrote “excommunicated” on Helmuth’s membership record.

This is where Truth & Treason becomes genuinely subversive, even prophetic. Whitaker’s development of this story long predates our current political moment. He is not making a parable about 2025. And yet the film lands with the force of direct address precisely because it tells the truth without editorializing, without winking at the audience, without reassuring us that we would have been different. Great art simply tells the truth—it is we who politicize it by mapping what is happening around us onto it. If the film feels political, it is because of the time we are in. It would not have been political twenty years ago.

The relevance does not end there. Recent research by historian Stephen O. Smoot reveals that Nazi intelligence files from 1933 to 1939 demonstrate a fundamental incompatibility between Latter-day Saint doctrine and Nazi ideology. In five hundred pages of secret police documents, the Nazis wrote that “the doctrine of Mormonism is completely incompatible with [Nazism].” The tragedy of Zander and others like him is not just that they were seduced by an ideology incompatible with their faith, but that they also compromised their faith for a group that would never truly accept them. This irony has marked the faith from the beginning: Latter-day Saints yearn to assimilate into groups and movements which use the Mormons to secure power, and then readily devour them once they have done so. The weeks before and after the film’s release have been a sobering reminder of this inescapable aspect which seems to haunt the Latter-day Saint identity.

The files Smoot uncovered also show that while some members sympathized with the Nazi Party—like Zander—many German Latter-day Saints did not approve of the regime and refused to participate. Latter-day Saints did not ubiquitously flock to the Nazi party, a pernicious myth sometimes perpetuated. Perhaps we allow this to be said of us because there isn’t enough Hübener in how we interact. Standing for truth against your own culture is tense work. It feels lonely. It’s easier to comply, to accept what feels beyond our power, to perhaps even be sorry for existing. We’ve learned to survive that way, and the sympathetic Bishop Zander exemplifies this.

A few years after Helmuth was executed, fellow Latter-day Saint and Navy officer “Tommy” Monson was preparing to fight in World War II. After all the other religious practitioners had been sent to their respective worship services, Monson stood alone, thinking himself to be the only Latter-day Saint in his camp, until he realized that there were many other “Mormons” standing behind him. In 2011, now as leader of the worldwide Church, President Thomas S. Monson dared Latter-day Saints to “stand alone,” citing a rhyme he had learned in Primary. Even while honoring and sustaining the law, there will always exist within Mormonism an ongoing paradox, reminding the faith of its own history of prophetic dissent on the basis of conviction. “Dare to be a Mormon. Dare to stand alone. Dare to have a purpose firm. Dare to make it known.”

Hübener shows us what that looks like when the stakes are life and death. And just as there were more with President Monson than he thought, so it was with Hübener. His friend Rudi Wobbe later reported that of two thousand Latter-day Saints in Hamburg, only seven were pro-Nazi, though five happened to be in Helmuth’s congregation. The boy who thought he stood alone was too late to discover that others stood with him. But it does not have to be too late for us. We are only a few generations away from Helmuth, whose devoted friends consulted on the development of this film. Stephen Smoot recently presented his research to Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf, whose father was a bitter opponent of both the Nazi and Communist regimes. Latter-day Saints need not conform to Nazis.

The final scenes offer no easy consolation. In the courtroom, Helmuth’s lawyer presents an escape: blame Karl-Heinz, sign the prepared statement, and save yourself—a proposition so absurdly hellbent on denying one’s faith, it’s worthy of a Book of Mormon villain. Helmuth sets down the document. Like Abinadi to the priests of Noah, he testifies that Germany is ruled by a lunatic fighting an unwinnable war. He tells the judge “your time will come. The judge will be judged, and truth will prevail.” He maintains that his “Father in Heaven knows I have done nothing wrong, and He will be the proper Judge in this matter.” The story gives catharsis without reward, and loss without visible redemption. And yet what remains is the example, the question of what we believe strongly enough to risk everything for.

Angel Studios was founded by Latter-day Saints and is headquartered in the heart of downtown Provo. Part of Angel’s business model includes only greenlighting films that pass its Angel Guild, a sort of B2C free market studio board, where thousands of paying members vote on what they want to see get distributed. This painstaking process has allowed Angel to cultivate a titanic evangelical audience—one which does not always reciprocate the same loyalty in return. Angel is frequently labeled “conservative” or “right-wing,” noted for championing the traditional values of their base in their work, and yet simultaneously scrutinized by that base for the religious identity of its owners. The distribution of the hit series The Chosen made this dynamic public: vocal segments of the show’s evangelical fanbase expressed such vocal alarm at the “Mormon involvement” behind the scenes, forcing creator Dallas Jenkins to repeatedly distance himself theologically. In these cases, Angel Studios ironically embodies that old tired attribute—tolerated by the credal Chistian, but on one critical condition: leave every trace of Mormonism at the door.

Perhaps this fervent gatekeeping is not without reason—we are “peculiar”, after all, or at least we’re supposed to be. As it would happen, the studio’s most distinctly Latter-day Saint film cannot help but also be its most quietly subversive. It has earned festival acclaim on the strength of its craft, not because it flatters the audience most likely to show up for a release. Truth & Treason refuses the easy comforts that often accompany stories of patriotism or obedience. It shows how propaganda can wear the costume of loyalty to country. It confronts the fact that, during Hübener’s trial, the Nazis themselves pointed to America’s history of Manifest Destiny as justification for conquest. And it asks whether a good and trusted bishop, committed to his nation, can mistake authoritarianism for righteousness. While critics have welcomed this honesty, the usual Angel box-office fervor has been notably absent, and the film’s returns have suffered because of it. Truth & Treason may land a little too close to home, leaving it, in the end, very Mormon indeed—by standing alone.

In a landscape crowded with reality-show and criminal caricatures of Latter-day Saint life, loud on conflict and thin on conviction, Truth & Treason feels like a needed course correction. It is the sort of “fair and accurate” representation the Church insists it longs for: a real Latter-day Saint authority figure who is well meaning, but flawed; and a Latter-day Saint hero who acts on his beliefs when it costs the most. Not popular, not profitable, but principled. Helmuth doesn’t sell a sanitized image of discipleship. He reveals what it looks like when a young Saint actually trusts his theology enough to let it govern his choices. Whitaker’s film assumes that we are capable of wrestling with complexity, that our faith can withstand scrutiny, that truth should not require translation to be understood.

As the world spins closer to days of chaos and tyranny and war and upheaval and “the earth… in commotion” and “the waves of the sea heaving themselves beyond their bounds”—to the last days, even—Latter-day Saints will find themselves deciding whether they would despise someone like Helmuth Hübener for his youth, or whether they would reckon with his treason as “an example of the believers… in charity, in spirit, in faith, in purity.”

Call me a zealot, but I believe Matt Whitaker, Kaleidoscope Pictures, and Angel Studios have become the instruments of delivering precisely the film we need right now, whether we want it or not. For years I’ve called for a new wave of Latter-day Saint cinema — one that embraces its Mormonism without apology, yet allows a universal and accessible story to lead. A cinema not weighed down by sentimentality, but willing to interrogate itself, and executed with excellence in every technical dimension. As I left the theater that night, I had to admit that this may well be the most important Mormon film ever made. And with its expanded series available to stream, it ought to be watched widely among Latter-day Saints, discussed seriously, and allowed to do its uncomfortable work.

This review is a chain letter. Pass it on.

Barrett Burgin is an award-winning writer and director from South East Appalachia. He has made several well-received films, including THE NEXT DOOR, THE ANGEL, JAVA JIVE, and A SCOUT IS KIND. Barrett received a BA in Media Arts from Brigham Young University, graduating with Honors in 2019.