This essay was originally written in Spanish. It was translated by Gisel R. Lance and reviewed by the author. Find the original Spanish text below the English version.

It is well known that, around 1765, a certain innkeeper named Dossier Boulanger began serving restorative meat broths and other succulent dishes to travelers and occasional wayfarers at his establishment on Rue Des Pulies, in Paris. To advertise, he hung a sign in Latin that read:

Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego restaurabo vos

Something like, "Come to me, men with weary stomachs, and I will restore them to you." This inaugurated a type of eatery that would be known worldwide as a restaurant, restoran, ristorante or restauracia—a place to eat something hot and nutritious to "restore" one's health. While it is true that the surname of our illustrious cook also gave its name to bakeries in French (boulangerie), that path would stray too far from the already scattered purposes of these wandering trains of thought.

It would not be surprising to suppose that some of these Parisian restaurants fed French soldiers who would participate, from 1776 onwards, in American lands, the liberation of the English colonies that would form the modern United States. They did so under the command of the Marquis de Lafayette and other Gaul officers. Nor would it be surprising to find, a few years later, among the patrons of Boulanger and its many imitators, those who would participate in the Revolution of 1789, under the motto "liberté, égalité, fraternité," that would eventually bring emancipatory ideas to Europe and the rest of the world.

Since both the establishment of the United States and the new ideas of freedom are considered necessary historical precedents for the restoration of the gospel, and since their French protagonists must have been fed somewhere, it is possible to establish an unavoidable and unexpected connection between restaurant and restoration.

While the revolutionary triple formula has always been considered a secular achievement, historian Jean-Louis Quantin has clearly demonstrated in his article "The Religious Origins of the Republican Motto" (Aux origines religieuses de la devise républicaine), (Communio No. XIV, May-August 1989) that Fenelón (François de Salignac de La Mothe-Fenelón) had already used it in The Adventures of Telemachus, a work inspired by scripture that preceded the French Revolution by 90 years.

Interestingly, the counter-movement that, from the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815, tried to reinstate the political absolutism of the Ancien Régime is also known as the period of the Restoration.

According to its etymology, the word "restoration" comes from the Latin "restauratio," meaning "the action and effect of repairing, renewing, recovering, or restoring something to its previous state or value." The word restoration also implies "a return... to a previous, original, normal condition, without defect, or the restitution of something that has been taken away or lost." The lexical components are: the prefix re- (back, again), statuare (to cause to stand, establish, determine) (hence its connection with "statue"), plus the suffix -tion (action and effect).

The New Testament precedent for the religious use of "restoration" is found in Acts 3:21:

“Whom the heaven must receive until the times of restitution of all things, which God hath spoken by the mouth of all his holy prophets since the world began."

The word Luke puts in Peter's mouth in this passage is found, like the whole book, in Greek, and it is apocatastasis (to set a thing in its original place, restore). The leader of the Apostles was speaking of a future time when things would be restored to their original state, and only then would the long-awaited return of Christ occur. The apocatastasis sparked a long dispute among the early fathers of the original Church as to whether it meant the end of times, the renewal of the Earth, or the forgiveness of sinners and non-sinners alike.

When the phrase was translated into Latin in the Vulgate, it read "in tempora restitutionis omnium quae locutus est Deus" ("the restitution of all things of which God has spoken")

When Luther translated it into German, apocatastasis became herwiedergebracht werde; "shall be brought back." Let us remember that, for Joseph Smith Jr., Luther's translation was the most accurate available, declaring, "I have been reading the German, and find it to be the most [nearly] correct translation, and to correspond nearest to the revelations which God has given to me for the last fourteen years" (History of the Church 6:307)

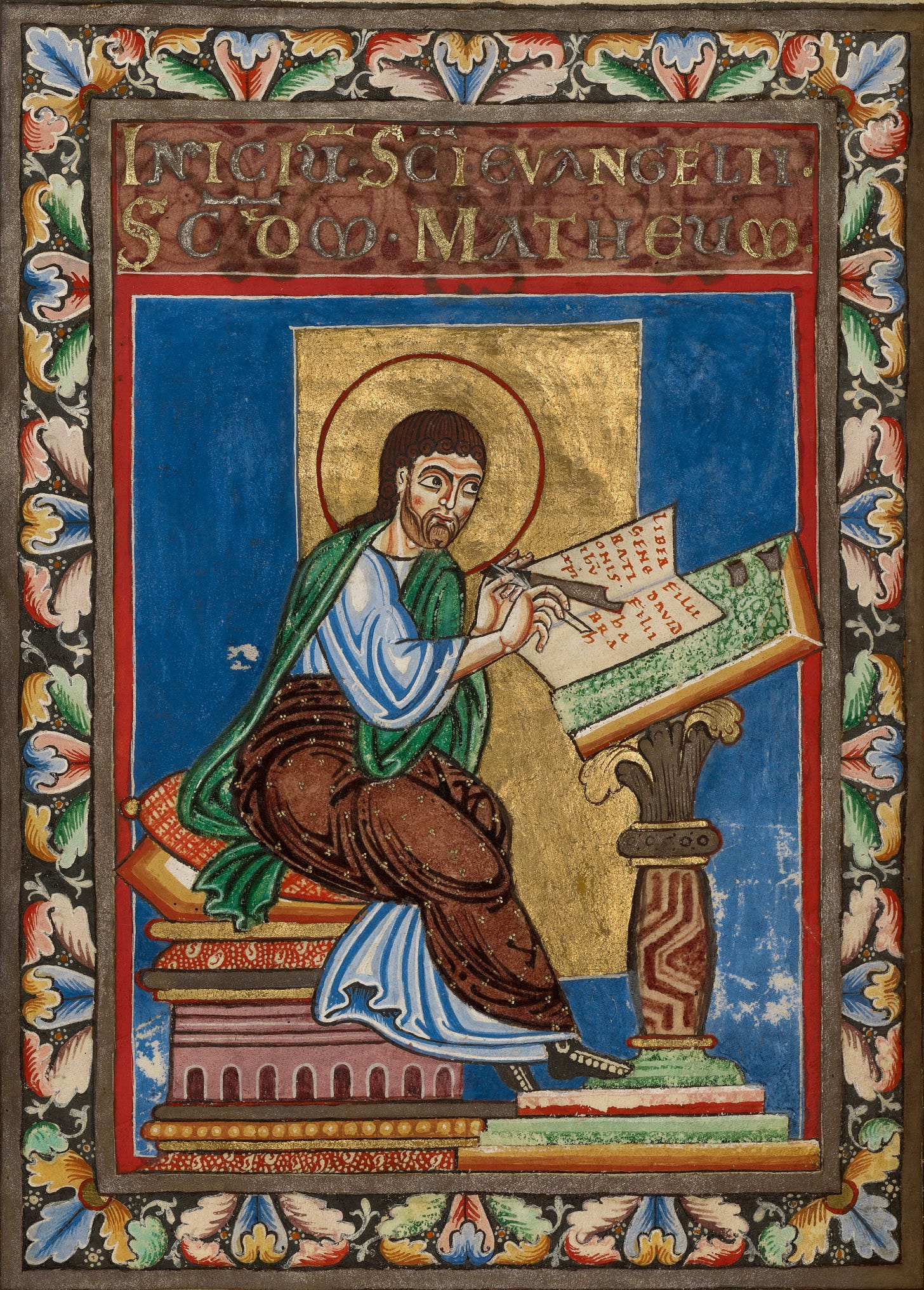

The same word appears in the mouth of Jesus, in the Gospel of Matthew:

“And Jesus answered and said unto them, Elias truly shall first come, and restore all things” (Matthew 17:11).

The concept is also present in Hebrew tradition, particularly in Hasidic Judaism and its reading of the Kabbalah, in the form of Tikkun Olam, "repairing the world." According to this mystical trend, the creation of the universe is represented as a vessel that could not contain the Holy Light and broke into pieces, thus needing repair. Through good deeds and the fulfillment of precepts, each person can participate in tikkun olam, literally helping to "restore" the universe and humanity itself.

As part of these musings, we could even draw closer to the Japanese art of kintsugi. Kintsugi (golden repair) is a centuries-old technique that involves restoring broken ceramic pieces. According to tradition, around the 15th century, the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent two of his favorite tea bowls to China for repair. The bowls returned fixed, but with unsightly metal staples that made them coarse and unpleasant to look at. Unhappy with the result, he summoned Japanese artisans to perform a better restoration. Thus emerged a new art form that consisted of joining the fractured parts with a resin varnish mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum. In this way, the reconstituted piece increased in beauty and value while displaying the object's history. Kintsugi eventually became a philosophy of life: in the face of life's adversities and "breaks," one must recover and use the "scars" to enhance and learn from them.

I find it interesting to bring this idea into contact with the thought of modern Latter-day Saint theology, for which the Restoration was not a singular event that occurred in a specific decade of the 19th century, rather a process still ongoing. Moreover, it was not merely the replacement of something lost but rather the gathering of the broken pieces of the gospel scattered across various cultures and religions.

The Book of Mormon tells us:

Know ye not that there are more nations than one? Know ye not that I, the Lord your God, have created all men, and that I remember those who are upon the isles of the sea; and that I rule in the heavens above and in the earth beneath; and I bring forth my word unto the children of men, yea, even upon all the nations of the earth? (2 Nephi 29:7).

The Prophet Joseph Smith declared: “One of the grand fundamental principles of Mormonism is to receive truth, let it come from whence it may” and to “gather all the good and true principles in the world and treasure them up.”

Undoubtedly, our incorporation of Protestant ways and the initial approach to Freemasonry had to do with this additional aspect of apocatastasis.

So, as a final conclusion to these musings, I believe that if we keep our minds open, we can actively participate in the glorious process of the Restoration.

Mario Montani lives in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, and served a mission in Uruguay. He works in the Public Affairs - Communication program. You can follow him online at MORMOSOFIA.

Translation provided by Gisel Lance and the author.

Es bien sabido que, allá por 1765, un cierto mesonero llamado Dossier Boulanger comenzó a servir caldos de carne reconstituyentes y otros platos suculentos a viajeros y ocasionales paseantes en su local de la Rue Des Pulies, en París. Para anunciarse, colgó un cartel en latín que rezaba:

Venite ad me omnes qui stomacho laboratis et ego restaurabo vos

Algo así como, “Venid a mí, hombres de estómago cansado, y yo os lo restauraré.” Inauguraría así el tipo de casa de comidas que se conocería en el mundo entero como restaurante, restoran, ristorante o restauracia, un lugar donde comer algo caliente y nutritivo para “restaurar” la salud. Que el apellido de nuestro ilustre cocinero haya servido también para nombrar a las panaderías en francés (boulangerie), es verdad, pero ese recorrido nos alejaría demasiado de los propósitos, ya de por sí dispersos, de estas divagaciones.

No sería extraño suponer que, en algunos de esos restaurantes parisinos, se alimentaron soldados franceses que participarían, a partir de 1776, en tierras americanas, ayudando a la liberación de las colonias inglesas que formarían el moderno Estados Unidos. Lo hicieron bajo las órdenes del Marqués de Lafayette y otros oficiales galos. Tampoco sería extraño hallar, pocos años después, entre los parroquianos de Boulanger y sus muchos imitadores, a los que participarían de la Revolución de 1789, bajo el lema de “liberté, égalité, fraternité” que acabarían llevando las ideas emancipadoras a Europa y el resto del mundo.

Siendo que tanto el establecimiento de Estados Unidos como las nuevas ideas de libertad se consideran antecedentes históricos necesarios para la restauración del evangelio, y que sus protagonistas franceses se alimentaban en algún lugar, es posible establecer un nexo ineludible e impensado entre restaurante y restauración.

Si bien la triple fórmula revolucionaria ha sido considerada siempre un logro laico, el historiador Jean-Louis Quantin ha demostrado claramente en su artículo “Los orígenes religiosos de la divisa republicana” (Communio Nº XIV, mayo-agosto 1989) que Fenelón (Francois de Salignac de La Mothe-Fenelón) la había utilizado ya en “Las Aventuras de Telémaco”, obra inspirada en las Escrituras y que antecedió en 90 años a la Revolución Francesa.

Curiosamente, al movimiento inverso que, a partir del Congreso de Viena de 1814-1815, intentó reinstaurar el absolutismo político del Antiguo Régimen, se lo conoce también como período de La Restauración.

Según su etimología, la palabra “restauración” proviene del latín “restauratio” y su significado es “acción y efecto de reparar, renovar, recobrar o recuperar, volver a poner algo en el estado o estimación que antes tenía.” La palabra restauración implica también “un retorno… a una condición anterior, original, normal, sin defecto, o la restitución de algo que se ha quitado o perdido.” Los componentes léxicos son: el prefijo re- (hacia atrás, de nuevo), statuare (hacer que se pare, establecer, determinar) (de allí el parentesco con “estatua”), más el sufijo -ción (acción y efecto).

El antecedente neotestamentario para el uso religioso de “restauración” se encuentra en Hechos 3:21

“a quien de cierto es menester que el cielo reciba hasta los tiempos de la restauración de todas las cosas, de que habló Dios por boca de sus santos profetas que han sido desde tiempos antiguos.”

La palabra que Lucas pone en boca de Pedro en este pasaje se encuentra, como todo el libro, en griego, y es Apocatástasis (poner una cosa en su puesto primitivo, restaurar). El principal de los Apóstoles estaba hablando de un tiempo futuro en el cual las cosas serían restauradas a su estado original y, recién allí, se produciría el tan esperado retorno de Cristo. La Apocatástasis trajo una larga disputa entre los primeros padres de la Iglesia original en cuanto a si significaba el fin de los tiempos, la renovación de la Tierra, o el perdón de pecadores y no pecadores.

Cuando la frase fue volcada al latín, en la Vulgata, se leía "in tempora restitutionis omnium quae locutus est Deus" ("la restitución de todas las cosas de las que Dios ha hablado")

Al traducirla Lutero al alemán, apocatástasis se transformó en herwiedergebracht werde; "será traído de vuelta." Recordemos que, para Joseph Smith, Jr., la traducción de Lutero era la más acertada que existía, declarando “la he estado leyendo en alemán y encuentro que es la traducción más correcta, y la que más se corresponde con las revelaciones que Dios me ha estado dando por los últimos catorce años” (History of the Chuch 6:307)

La misma palabra aparece en boca de Jesús, en el Evangelio de Mateo:

“Respondiendo Jesús, les dijo: A la verdad, Elías viene primero, y restaurará todas las cosas” (Mateo 17:11)

El concepto también se encuentra presente en la tradición hebrea, particularmente en el judaísmo jasídico y su lectura de la Cabalá, bajo la forma de Tikún Olam, “reparar el mundo.” De acuerdo a esta tendencia mística, la creación del universo está representada como un recipiente que no pudo contener la Luz Sagrada y se rompió en pedazos por lo que necesita reparación. Mediante las buenas acciones y cumplimiento de los preceptos, cada persona puede participar en el tikún olam, ayudando a “restaurar” literalmente el universo y la propia humanidad.

Como parte de estas divagaciones podríamos aún acercarnos al arte japonés del kintsugi. El kintsugi (reparación dorada) es una técnica centenaria que consiste en la restauración de piezas de cerámica que se han roto. Según la tradición, allá por el siglo XV, el shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa envió a China dos de sus tazones de té favoritos para ser reparados. Los tazones retornaron arreglados, pero con unas feas grapas de metal que los volvían toscos y desagradables a la vista. El resultado no le agradó por lo que convocó a artesanos japoneses para que hicieran una mejor restauración. Surgió así el nuevo arte, que consistía en unir las partes fracturadas mediante un barniz de resina mezclado con polvo de oro, plata o platino. De este modo, la pieza reconstituida aumentaba su belleza y valor al mismo tiempo que mostraba la historia del objeto. El kintsugi acabó convirtiéndose en una filosofía de vida: frente a las adversidades y “roturas” de la vida, hay que recuperarse y utilizar las “cicatrices” para valorizarlas y aprender.

Me parece interesante poner esta idea en contacto con el pensamiento de la moderna teología SUD para la cual, la Restauración no fue un hecho puntual que se produjo en una determinada década del siglo XIX, sino un proceso que aún está en curso. También que no fue únicamente la reposición nueva de algo que se había perdido sino el recoger los pedazos rotos del evangelio que se encontraban dispersos en diversas culturas y religiones.

Nos dice el Libro de Mormón:

¿No sabéis que hay más de una nación? ¿No sabéis que yo, el Señor vuestro Dios, he creado a todos los hombres, y que me acuerdo de los que viven en las islas del mar; y que gobierno arriba en los cielos y abajo en la tierra; y manifiesto mi palabra a los hijos de los hombres, sí, sobre todas las naciones de la tierra? (2 Nefi 29:7)

El Profeta Joseph Smith declaró que “uno de los sublimes principios fundamentales del mormonismo es recibir la verdad, sea cual fuere su origen” y “recoger todos los principios buenos y verdaderos que hay en el mundo y atesorarlos.”

Sin duda, nuestra incorporación de formas protestantes y el acercamiento inicial a la masonería tuvieron que ver con este aspecto adicional de la apocatástasis.

De modo que, como conclusión final de estas divagaciones, creo que, si mantenemos abiertas nuestras mentes, podremos participar activamente en el glorioso proceso de la Restauración.