Men in Blue

Thee Lift Me, and I'll Lift Thee, and We'll Ascend Together

Over the years, I’ve heard my family talk about a special place. They’ve briefly mentioned the work performed inside, but mostly they’ve emphasized the perspective I would gain from my day there. They have told me about the unique feelings I would experience—about the love and the pain and the miraculous power of Christ’s Atonement. The day before, I made sure I had everything—my distinct clothing, my approved recommend that required many interviews, and a happy attitude. Before I left, my parents told me they loved me and that they were proud of the decision I had made.

That beautiful spring morning, I presented my paperwork at the door and entered the San Quentin State Prison—California’s maximum-security prison.

My background screening had taken months, and I had to dress modestly—avoiding the apparent gang colors of red or blue, and, of course, no prison neon orange or yellow. All of the inmates involved in the program were dressed in denim, and they frequently referred to themselves as the “men in blue.”

I was part of an Interfaith Restorative Justice course where two dozen of us civilians would spend the day interacting with inmates. My role was to listen to their stories and encourage them to make restitution for their wrongs. The “men in blue” were a select group of men from the prison who were actively working to acknowledge their wrongs and find personal and spiritual transcendence in their repentance.

The theme of the day was “Live to Forgive.” The title struck me as funny. It seemed to me that it would more accurately be called “Live to Apologize,” given that these men were violent perpetrators. Many of them had committed serious felonies, including murder, terrorism, and kidnapping. Why did they need to forgive?

To begin, I was instructed to pair up with an inmate and hear about his life experience. I remember talking to Tommy, an older gentleman committed to life in prison who was responsible for three deaths thirty years before. He told me that his only daughter had finally reached out a year ago and wanted to visit him. He was so excited to see her and have her in his life. On her way to San Quentin, a semitruck hit her car and killed her. In his despair, Tommy decided to pray for the first time in years. The Spirit prompted him to apply to this restorative justice program, and he had since found meaning and solace in his anguish. “Thank God for prisons,” he said, “because without them, I never woulda found him.”

To my surprise, the volunteers were subsequently encouraged to open up about their own experiences. I remember sharing the insecurity of going into my senior year of high school, my own fears and petty cruelties. Though Tommy and I had different life experiences, we were able to connect and help each other. Tommy listened intently to me and asked me follow-up questions. He wasn’t just listening to me. He was seeking to understand me and my circumstances. I had imagined that my primary role would be that of a minister. I had no idea that I would be ministered to as well.

That day, as I spoke with Tommy and the other men in blue, I discovered a uniting theme that linked these men together. They too had been harmed. They spoke openly of their extreme circumstances, and my eyes were open to just a sliver of the pain and suffering that exists in this world. Grown men broke into tears as they reflected on their painful childhoods. And gradually they acknowledged the terrible harms that they had experienced and eventually the harms that they had inflicted on others.

These were not the heartless men I imagined I would find in prison. Most were the products of a vicious cycle of poverty and violence that perpetuated itself throughout generations. It was hard to imagine that anything positive could come from all they’d been through, but as they spoke, I began to understand the need for them to acknowledge their pain and forgive those who harmed them when they were younger. This is the bedrock of the restorative justice program.

From the beginning, I was inclined to believe that these men in blue were evil. Before I could hear their stories and their experiences, I had made a judgment that their actions were solely reflections of their disposition and agency. I was wrong.

As humans, we are primed to judge others by their actions. This flaw is so common that it has a name in the field of social psychology: the fundamental attribution error. The fundamental attribution error suggests that humans have a tendency to overattribute the behavior of others to their disposition as opposed to the circumstances that surround the behavior. However, when it comes to judging and assessing ourselves, we overattribute our behavior to our circumstances as opposed to our disposition. That is, we consider others responsible for their poor decisions while we see our own choices as merely products of our environment.

Such a double standard can lead to spiritual blindness. In Matthew 7, Jesus teaches, “Judge not, that ye be not judged. . . . And why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye? … Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.”

If we see the wrong decisions of others as originating from pure intent to do evil, we cease to seek to understand them. Had I not befriended Tommy and the other men in blue, I would have continued to judge from my corner of contempt. I would have forgone the opportunity to both minister and be ministered to.

In “Jesus: The Perfect Leader,” Spencer W. Kimball states, “Jesus saw sin as wrong but also was able to see sin as springing from deep and unmet needs on the part of the sinner.”

Though there is agency involved in sin, circumstance and need also play a role in our actions. When we minister to others, we find ways to meet their needs and extend to them an opportunity to grow closer to God. Thus, personal righteousness is not only a means toward our salvation, but a means toward the salvation of others.

About halfway through the restorative justice service, I had a moment of doubt, wondering, “What if one of the prisoners decided to attack me? Who would be there to save me if I suddenly became a target?” Panic overwhelmed my body as I looked for an answer. I looked around for the correctional officers who were guarding the door, who would be there to help me if a prison riot broke out. In the room of over 150 inmates, there could not have been more than three correctional officers to break it up if things got out of hand. And then the answer came to me.

It wasn’t the correctional officers who would help me. It wasn’t the other volunteers. It was the men in blue.

It was the men I had ministered to and who had ministered to me. It was the men who had poured out their souls and opened my heart toward a new perspective. Despite their circumstances, I trusted that these men who were part of this program would care for me if my life was placed in harm’s way. Deep down in that dark and forlorn prison, the Spirit filled my heart.

My eyes were opened to the divine nature in these men. At the end of the service, the men in blue stood up to sing:

Amazing grace—how sweet the sound—that saved a wretch like me! I once was lost, but now am found, was blind, but now I see.

Dashiell Miner is a first year medical student at Stanford Medicine. He cares deeply about questions of faith and community.

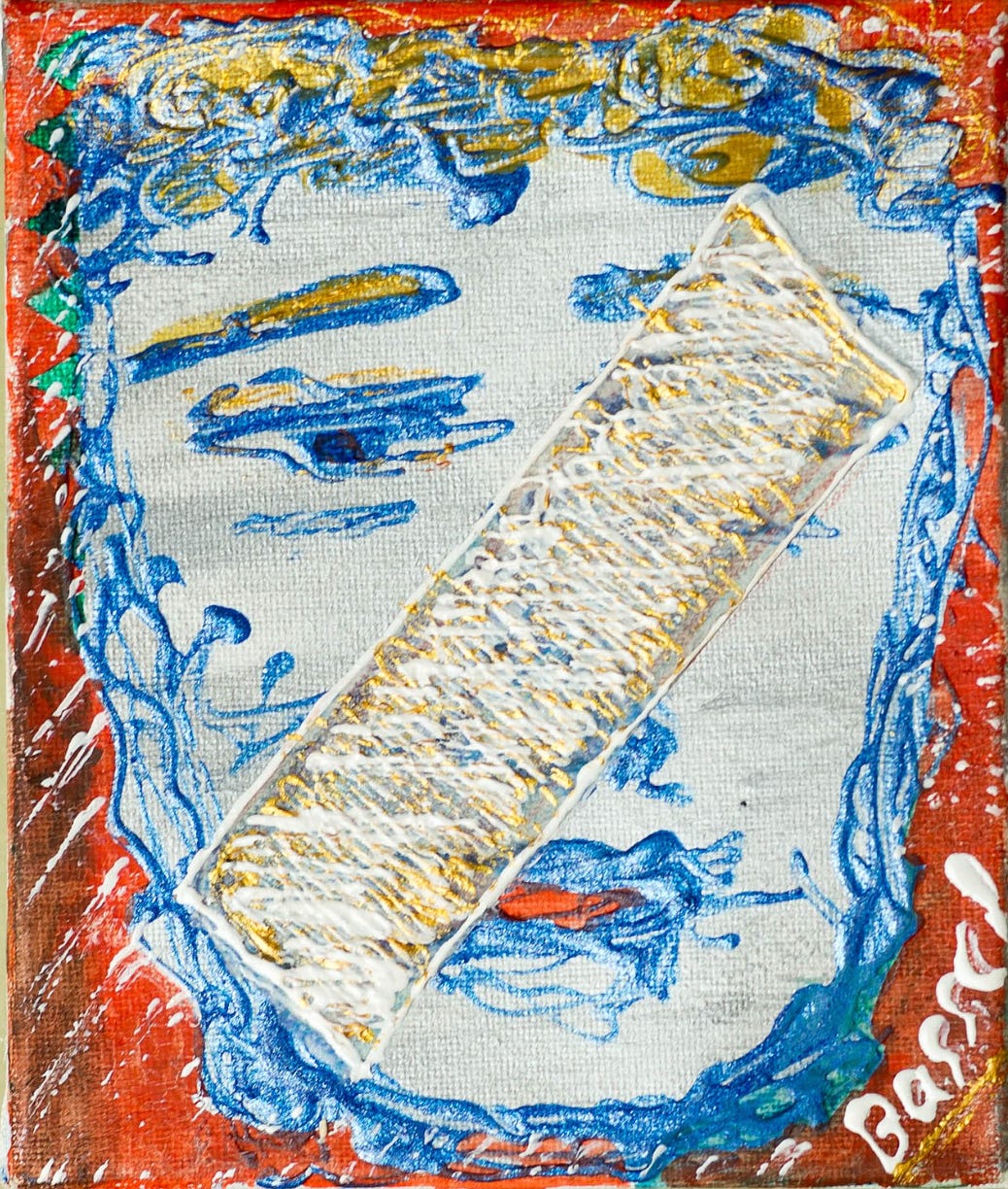

Art by Bassel Khartabil.

Excellent article - thank you for sharing your experience