Sara Levy was dreading the next Relief Society lesson she had to teach. The subject was marriage: that sacred covenant, so frequently profaned. She had no idea what to say that would be appropriate for everyone. There was a time, of course, when she wouldn’t have concerned herself with such things, but the trouble with being the bishop’s wife was that a woman started to worry by proxy about everyone. Being so close to the calling gave her most of the stress and none of the keys.

Well? What was a mere teacher to do? She decided to counsel with her president, Fruma Selig. She’d look for advice, and maybe recognize a little revelation in it. On the Tuesday evening before her lesson, she took a bus to the Selig apartment to see what wisdom she could glean.

“My worry is that everyone’s lives are so different,” Sara said, as Fruma began to fill a kettle to fix them some herbal tea. “Not everyone has the ideal situation, like Tzipa and Lemel do. How many Feiges do we have in our ward who can’t stand their Aarons? And sisters like you—it must be difficult to talk about marriage when you’re divorced.”

Fruma shrugged. “Don’t make it too complicated,” she said. “My marriage, for all its faults, taught me a great deal about the worth of souls. Especially my own.” She set the tea kettle on the stove. “I don’t mind hearing people talk about what a healthy marriage looks like: it reminds me I made the right decision.”

“But what if the lesson veers into the importance of shared faith and being married in the Church?” Sara asked. “I don’t want to make Shayna feel bad for having married in Germany. And it’s hard for Mirele Schwartz to feel like her marriage is good enough when her husband is retired from all religion.”Fruma laughed. “Stefan is in the ward now. We don’t worry about what happened before, because each day has trouble enough of its own. And no matter what the lesson is, Mirele will feel like she doesn’t measure up. You can’t blame the topic for that!”

Sara had hoped for more sympathy, but she held out for some guidance. “What about Leah Kantor? She’s never married. And she’s no longer young. But also not old enough to write off the whole business for good. It’s such an awkward, in-between age.”

Fruma was staring at the teapot, but it wouldn’t boil. “She may not be married,” she acknowledged, “but she’s hardly alone. Remember the chickens? The goats?” She looked over at Sara. “Lots of people spend their lives single these days.”

“But most people aren’t in the Church!” Sara said. “It’s one thing to be single if you live with both feet in the twenty-first century. When your faith prefers to mix this and that millennium, the situation’s different.” At this, Fruma gave up on hovering over the teapot and finally sat down to listen. “We’re going to teach that marriage is important,” Sara said. “That’s practically a fourteenth article of faith—the question is how to tell people what their marriage should look like without making them feel judged.”

Fruma sighed. “I understand the problem,” she said. “But what’s the use of telling people when and how and who to marry when the whole market is broken? If finding anyone decent feels like a fluke?”

Now they were getting somewhere. “Exactly,” Sara said. “I don’t want to blame any given person. None of this is their fault.” That’s when inspiration hit her. She sat back in her chair “The trouble is that the community isn’t doing enough. We’ve abdicated too much responsibility.”Fruma leaned forward. “What do you mean?” she asked. “Responsibility for what?”

“There was a time when people didn’t have to work so hard to get married. Because the community helped make it happen for them.”

Fruma frowned. “We have activities. And there are stake dances, regional gatherings for the single adults. What more do you think we should do?” “I know exactly what to do,” Sara Levy said. “I’m going to talk to my husband about calling a matchmaker for our ward.” Across the room, the teapot began to whistle. The sound was the perfect accompaniment for the expression on Fruma’s face.

“No,” Bishop Levy said. It was late. He’d just gotten back from a meeting. But Sara wanted to strike while the iron was hot. “What do you mean, no?” she insisted. “You haven’t even considered it yet, Mattheusz!”

“If I could invent callings, do you think Oskar the Miser would be our librarian?” He shook his head. “I’m not the prophet. I’m just a bishop.”Sara sighed. “All right, then maybe Matchmaker is not a new calling. But you could add it as an assignment to a calling that already exists.” He ran a hand through his hair. That meant she had him thinking. “Senior missionaries do it all the time! Why not give the same responsibility to the activities committee—or the Relief Society’s compassionate service coordinator?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “These days, people like to find their spouses for themselves.”

“No, they don’t,” she snapped. “You know better than that. No one likes having to date. All the figuring out who to ask and what to say and how to pretend to be: it’s exhausting. People are so desperate for help, they invented the internet just to make connections.” She crossed her arms. “If religion can’t compete with technology, what place will it have in the future?”

He lifted his hands in surrender. “All right. All right. That’s enough.” He looked at her, weighing some thought. “But before I give anyone this kind of assignment, I want you to try it. Make one match, one good match, and we’ll see.”

“And this is for a Church assignment?” Leah Kantor asked. She cradled her cell phone between her shoulder and her ear. “An experimental Church assignment?”

Where had she put her earbuds? They must be somewhere close. “No, I’m happy to help. I like to do my part for our ward . . . It’s nice you’re excited; someone might as well be . . . all right . . . yes, I can come to your house . . . I’ll talk to you later . . . Yes, later . . . Goodbye.”

Had she left them on the kitchen counter after her cousin called? Yes, that was it.

Leah found her earbuds and put on some music—Bedřich Smetana’s “The Moldau”—to keep her company on her evening walk.

As she thought over her conversation with Sara Levy, she realized she wasn’t entirely sure what she had agreed to. If a matchmaker set up a meeting, that wasn’t exactly a date, was it? That is, she didn’t have to pretend to be interested in impersonating the kind of attitudes or behaviors you saw in films. For heaven’s sake, she was in her early forties. By now, she hoped she had grown out of needing to impress anybody. If it happened indirectly, through her art, that was one thing. But with her charm? Or her wit? Or her body? Please no. She was quite content with all those things, but she had no intention of parading them.

Then again, she’d never been to a matchmaker’s meeting. If she could be direct and frank, that could be refreshing. Was she even still open to the possibility of a partner? That was a difficult question. But if you stripped away all the frills of courting and got straight to the negotiations, at least the conversation might be interesting. Menachem Menashe was a mildly interesting man. Not young enough to be annoying or old enough to have grown set and dull; if she said so herself, the forties were a happy medium. And in this unexpected setting, she might get to see a side of him that she’d never met before.

Or maybe the whole thing would be a disaster. That would also be all right. If it was, Sara Levy would probably never ask her to come to a meeting again. And because the request had come through Church, God would owe her a favor.

After Sara Levy reached him, Menachem Menashe was one part intrigued and three parts uneasy. The appealing part was that he had never imagined himself with Leah Kantor. It was something only a matchmaker could have come up with—and maybe that would help. He suspected that he would have married in the old days, and wondered absently how it would have gone. After all, it’s one thing to resign yourself to a relationship. It’s quite another when you’re expected to choose.

The long process of wanting and pursuing and selecting and agreeing, which a person had to go through today to get married, was beyond him. But with someone else starting the process? It was probably still beyond him. He would nevertheless do his best to keep an open mind.

What did he know so far? As far as he could tell, he and Leah had a lot in common. They were both Saints. They were both single. They both read books. If nothing else, those three things were more than most couples in history shared before the spread of women’s education. And it’s not like modern people who chose their own partners necessarily wound up with much more!

He began to think about what he would even want to ask in their interview at the Levy house. He had never been to a matchmaker’s meeting before.

At last, the night arrived. Sara Levy had warned them each to eat dinner on their own—there was no need to test etiquette on a first meeting by having them navigate a whole meal—but she had laid out some rugalach, because a little sweet for the nerves never hurt. And to go with it, she’d made them cups of barley coffee. Was it good? Not particularly. But it honored the Word of Wisdom and it went well enough with a dessert.

Menachem arrived first. He was dressed well, if the tiniest bit rumpled from his studies. Ah, well: people married professors once in a while, didn’t they? He was certainly no worse.

When Leah arrived she was dressed neatly, if plainly. She had brought along a notebook. Whether it was to keep track of Menachem’s responses or to write in if she got tired of listening to him, Sara couldn’t tell. Honestly, Leah already looked a little bored. But maybe that would change.

“I’d like to thank you both for agreeing to participate,” Sara said. “Seeing as you are both adults, I left your parents out of this meeting, but I thought I would start with the questions they might ask. You can both answer, and then I’ll be out of your way so you can talk amongst yourselves. Because this is an experiment, I hope you’ll keep me updated. And I’ll call tomorrow to see if you can give me any feedback you might have on the process.” She cleared her throat. “Any questions before we begin?”

Leah raised her hand. “Is there a certain time you’d like us to stay until?”

“I’m just glad you came in the first place,” Sara said. She looked down at her notes. “First question: do you come from a good family?”

“Yes,” Leah said.

“Not exactly,” Menachem admitted.

“Second question: how are your prospects? Economically, I mean.”

“I live simply, but comfortably,” Leah said.

“I live simply,” Menachem said.

“Third: do you keep the Sabbath?”

“Yes,” said Leah. “Religiously,” said Menachem.

“What are your expectations about marriage?” Sarah asked them.

“I don’t,” Leah said.

Menachem looked over at her as if surprised at the point of connection. “Neither do I.”

That was all the questions Sara had written in her book. She briefly considered following up about Menachem’s family but decided it was not her place to pry. Besides, if a person defined family broad enough, everyone’s relatives were a mess. “Well,” she said instead, “Since you are both religiously observant, with economic differences that are unintimidating and expectations that are compatible, I can in good conscience recommend that you consider this possibility. I’ll leave you to discuss whatever is on your minds. Please be as open and honest as possible: eternity is at stake.” And with that, she left the room.

Leah began before Sara made it to the end of the hall. “What is the worst thing about you?” she asked.

Menachem thought. “It’s difficult to pick,” he said. “I am deeply obsessive. Also haunted by my own insecurities. Probably one of those.”

Leah appreciated the rapid candor. “What insecurities specifically?” she asked.

“Oh, the usual,” Menachem said. At least, he assumed that they were usual. He wasn’t in the habit of comparing notes. “Am I good enough? Am I worth people’s time? Does my existence justify the burden it places on the fabric of the earth?” Of course, it went deeper than that. It was hard to put into words, but he supposed he owed it to her to try. “Would my life be better if I were invisible and intangible, a silent witness to creation but without any capacity to interfere?” he said.

Leah picked up a rugalach and took a bite. “And are you the sort of person who seeks out constant affirmation in a fruitless effort to calm these insecurities?” The thought of asking directly for such a thing almost made him want to gag.

“Not really,” Menachem said. “I’m more the internal, spiraling type. I obsess until I sweat and my mind locks up until, gradually, it becomes exhausted by the strain. After that, things usually don’t seem so bad

“Oh,” Leah said. “That doesn’t sound like too much, then. A person could live with that.”

“I mean . . . I do,” Menachem told her. “I meant another person. You wouldn’t actually be the kind of burden you’ll always be worried about is what I’m saying.” The sentiment was unexpectedly kind. He wasn’t sure he could completely believe it, but he was glad to have the words there to try. “Thank you,” he said.

She picked up her barley coffee and took a sip. It was pleasurably hot. “Now you ask me something.”

Menachem still felt blank, but it would be rude not to at least try to probe at their hypothetical compatibility. “After you shower, do you remember to pull the curtain back shut? Or do you often leave it open and have to clean it later?”

“I pull it back shut,” she said. The question spoke well of him. “Prevention is better than cure.”

“If you had a free weekend, would you rather spend it in a city or outdoors?”

“City. One that’s old and overgrown.”

“I know you conduct the choir. But do you like music?”

“Desperately,” Leah said.

“If you had to choose between a randomly selected Slavic composer and a randomly selected German—”

She smiled. “Slavic.”

“Do you prefer the library or a bookstore?”

“It depends on the book. To pass an hour? Library. But if I know I’m going to love it, I want it to be mine.”

Menachem paused. He picked up a rugalach. It was flaky and just the right amount of soft.

“Why aren’t you married?” Leah asked.

Menachem swallowed. “The thought ties my stomach in knots.”

Leah laughed. “Marriage is quite a tradition, isn’t it?”

Menachem nodded. “I’m glad it exists in the world. Somewhere. And in the next world, likewise.”

“The idea of another person in my life exhausts me,” Leah said. “I’m happy as I am. I like my space, both physical and psychological. But who knows? Maybe the compromises would be worth it.” She bit her lip. “For example, I’d love to know what it’s like to have sex with a man.” That was another thing they had in common, Menachem Menashe thought. He’d often wondered about the exact same thing.

“The troubling thing about marriage,” he said, “is that it’s supposed to work on so many levels at once. You’re expected to be practical, but also passionate. To have things in common, while also complementing each other. Marriage is supposed to be the basis for intergenerational relationships—and also the most intensive sort of friendship. It’s supposed to be egalitarian and personalized, but with roles that hold up well under pressure and on autopilot.” He looked at her sadly. “I think, once upon a time, when some of those things were separate, that maybe it could’ve worked for more people. But now? It’s too much. For me, it feels like much too much.”

She took another long, slow sip of the Levys’ fake coffee. “I think I agree,” she said.

So as not to disappoint Sara Levy, they talked for a long while before they left. But not about the prospect of marriage anymore. They talked about Smetana. And the way rivers wind, gaining force as they flow out toward an unseen river or lake or sea. No one can predict the course in advance. Only appreciate the music of the river’s movement.

He offered to walk her home. She laughed at the offer first: since when did she need someone to walk with? But then, realizing she didn’t know the best way to end a Mormon matchmaker’s meeting, she agreed.

“Do you think we’ll feel different after we’re dead?” Menachem asked as they approached her building.

“I hope so,” Leah said. “I’m looking forward to being able to fly and walk through walls and all those kinds of things when I’m resurrected.” She made a face. “I’m also hoping my taste buds change, just in case Jesus offers me fish.”

“I meant about relationships,” Menachem said. “Do you think God will change what I want? And if he does, will he also change what I want to want? And if he does—if he can—what’s the point of working with the me I am in the meantime?”

Leah laughed. “I thought you said you were the kind of person who spirals internally,” she said.

“I’m not asking you for reassurance,” Menachem said.

“What then?”

He frowned. “A sounding board? For my thoughts to be refined? Understanding?”

Leah nodded. “All I know is that whatever relationships we start here have echoes there,” she told him. “So I’m glad to be your friend.”

The next day, Sarah Levy called Leah, then Menachem. Each gave their reports by phone, rating their experience on various scales, explaining what had happened, and informing her that from them she should not expect any courtship.

“How did it go?” Matteusz asked when he got back from his bishopric meeting. “Did you make one good match yet?”

“A great match,” she told him.

He raised his eyebrows. “Really?”

“Some of the best matches are never going to be marriages,” she said. “But they’re made in heaven all the same.”

James Goldberg is a poet, playwright, essayist, novelist, documentary filmmaker, scholar, and translator who specializes in Mormon literature.

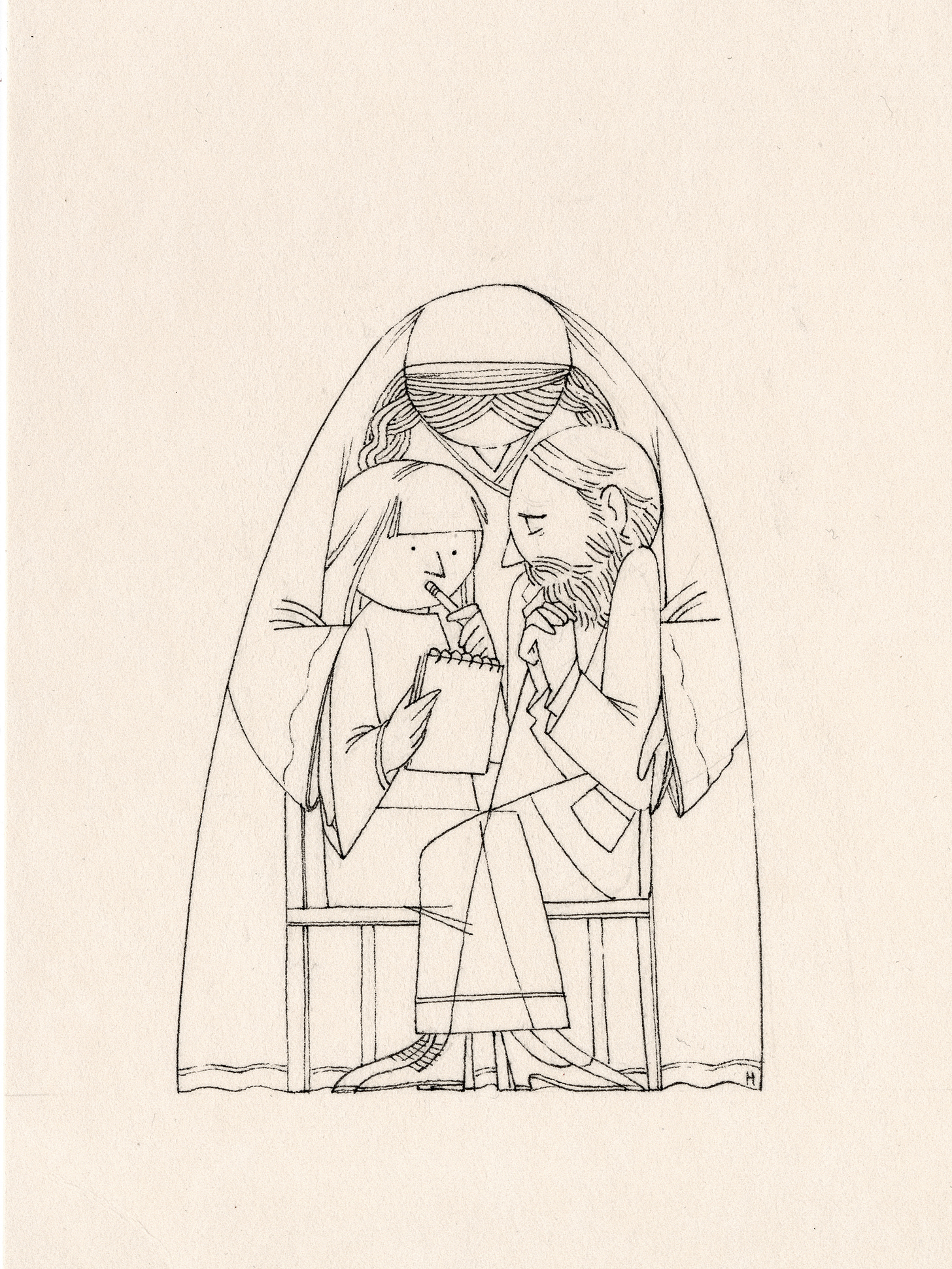

Artwork by David Habben.

To order the complete Tales of the Chelm First Ward, click here.