Longing is the Essence of Faith

An Interview with Susan Cain

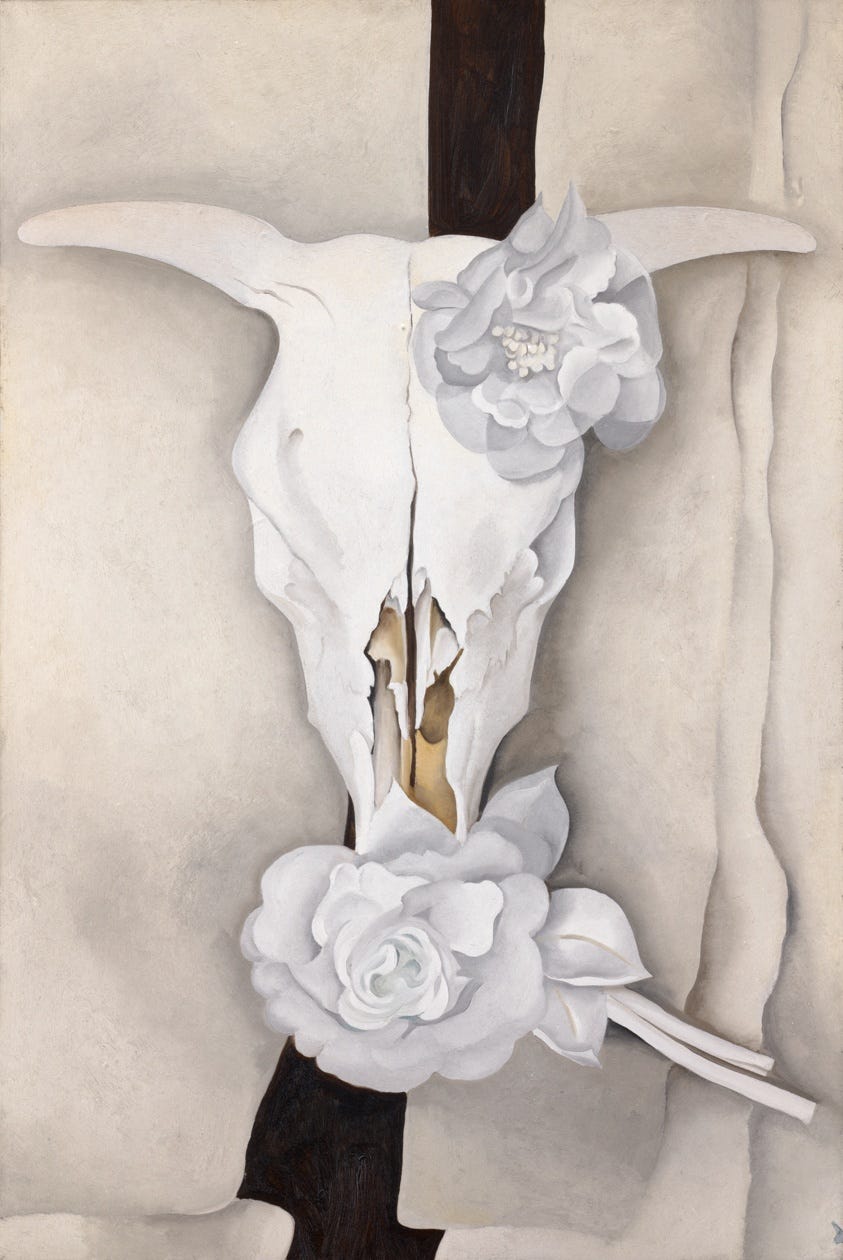

“Light and dark, birth and death—bitter and sweet—are forever paired.” -Susan Cain

Susan Cain is the bestselling author of “Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking” which spent nine years on The New York Times best seller list, and has been translated into 40 languages.

She recently published a new book: “Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole.” Aubrey and Tim Chaves, hosts of the Faith Matters podcast, interviewed Cain for the podcast earlier this year. Their conversation highlighted the power of bittersweetness for creating art, resilience, and divine connection and what we miss when our culture refuses to confront mortality.

Let’s begin by talking about how this book got started.

It came from an experience that I have had over and over again throughout my life. I was in my early twenties, in law school, in my dorm waiting for some friends to pick me up for class. We were going to go together and I was listening to music blasting on my stereo. It was kind of bittersweet longing music, probably Leonard Cohen or someone like that. And my friends thought it was hilarious that I was listening to what they called “funeral music,” and they were teasing me about it. I thought it was funny, and I laughed, and we went to class. And in some ways that was the end of the story.

But I kept thinking about this for decades: what is it in our culture that makes it funny to listen to music that's beautiful but sad? And also, what is it about the music itself? Whether it's Leonard Cohen or Nina Simone or Adele or whoever it is for you, you listen to that kind of music and you don't really feel sad. You feel a kind of tidal wave of love, and you feel a sense of connection to the musician and to every other human who has ever had the experience that the music is trying to express and transform into beauty.

I started to realize that those were some of the most profound experiences of my life and that the music was pointing me in a direction of a deeper truth and meaning that we don't get to talk about enough in our culture. There really is what I call a bittersweet tradition that has been with humans across the centuries and across cultures. We find it in our religions and wisdom traditions, especially this sense of sorrow and longing as a kind of gateway to transformation.

You say in the book that sadness is the ultimate bonding agent. Could you explain that?

We've all had this experience: You're there with your friend during an hour of need, or you’re having a problem and you share it with a friend. There's something about the nature of friendship—you could almost define a deep friend as being the one you would share your sorrow with.

Here’s a kind of evolutionary take on it: Darwin was a gentle and melancholic type of soul, and he was kind of horrified by the cruelty that he found in nature. But alongside that cruelty and survival-of-the-fittest mechanism, he also noticed that among humans—among all mammals—there is this instinctive thing that happens: when one mammal sees another in distress, the witnessing mammal feels compelled to act, to do something about that distress. It's like the distress of another becomes our own.

Darwin wrote in his book The Descent of Man that the feeling, the visceral experience of another person's distress, is actually the strongest impulse of all in animal life. It wasn't that he was like Pollyanna and not seeing the darker, more violent side of our nature. But he really did see this kind of compassionate instinct.

And then 150 years later, a psychologist at Berkeley, Dacker Keltner, started studying this compassionate instinct. He studied the vagus nerve, the strongest bundle of nerves in our bodies. When we see somebody who's sad, our vagus nerve becomes activated: we want to bond with them and do something about it. And all of this comes from the human impulse to protect newborn infants who arrive in this world completely vulnerable and in tears.

This is the way mammals and humans have been designed. To show up for each other's tears doesn't mean that we have to be stuck in that mode all the time—the baby stops crying and you have a nice snuggle—but it's all part of the experience.

Could you talk about some of the ways we can develop the empathy and humility that connects us to the people around us, even if they're in pain?

I was really interested to find in the research that the simple act of bowing or lowering our heads puts us into that state of humility and empathy. And I started thinking about all the different traditions in which bowing is incorporated.

Think of all the different Japanese social traditions where people greet each other with very specific types of bows. You see it in Islam, you see it in yoga. It feels like an acknowledgment of the other with that simple act of lowering your head.

And prayer too, right?

Yes. It actually runs so counter to the way we are taught to present ourselves in everyday life. The idea of lowering your head in a business meeting—you would never do that. You're supposed to stand tall with your big smile. There's an intuition in prayer that recognizes that the mechanism of standing tall all the time doesn't take us all the way there. It's right for certain circumstances, but not all the time.

We sometimes attach a moral value to being cheerful and optimistic, and we see those attributes as expressions of faith. I wonder if some people might see embracing longing as an admission of a spiritual deficiency, or as a lack of trust in God. Could you reframe that for us?

Longing is the very essence of faith. You see this in different religious traditions. Dating all the way back to the fifth century, Gregory the Great talked about this feeling of compunctio, which he called the Holy Tears. He described the Holy Tears as a feeling of bittersweetness because you see the difference between the world that you long for, the divine that you long for, and the world in which you find yourself currently. There's something about the recognition of that gap that is said to bring you ever closer to the divine.

You see this in all the traditions. There's the longing for the Garden of Eden, there's the longing for Zion. In the Sufi tradition, which is the mystical side of Islam, there's the longing for the beloved of the soul, which is the way Sufis sometimes talk about God.

You might have heard of the poet Jalal al-Din Rumi. He's a twelfth-century Sufi poet who happens to be the best-selling poet in the United States. He's got this amazing poem called “Love Dogs” in which he describes a man who is praying to God. A cynic comes along and observes this and says to him, why are you bothering to do this? Did you ever get an answer back? And the guy says no, I actually never did. And he's very disturbed by this.

That night he falls into a fitful sleep, and he has a dream in which he's visited by Khidr, who is the guide of souls. Khidr asks him why he stopped praying, and the man explains. I have the words that Khidr says to him literally taped up on the lamp next to where I am now talking to you, because I find this so profound. This is what Khidr says to this man: “This longing you express for the divine, this longing you express is the return message. The grief you cry out from draws you toward union. Your pure sadness that wants help is the secret cup.”

So longing is the essence of what brings us closer. Not what fails to appreciate God.

You noticed a potential contradiction between that Sufi teaching, the longing for the beloved, and Buddhist teachings about how a lot of our suffering comes from our attachment to things that we don't need to be attached to. Could you talk about how you resolved that contradiction?

I went to a Sufi retreat led by Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee, whose Youtube videos I would totally recommend. At the retreat, I asked him this question, and he lit up as if he'd been waiting for somebody to ask it.

And he said, “No, no, no. These are completely different states.” When we talk about the value in longing, we're not talking about the longing for a piece of chocolate cake or for a better house or car or something, even though all those are understandable desires.

The Sufi longing, I think, is more about the longing for the divine—or in secular terms, you could say the longing for that which is most beautiful and good and true. There's a sense of longing for that state of perfection and truth and goodness we can never quite attain in this world, but the longing for it brings us ever closer.

There's so much peace there. And also, paradoxically, there’s a kind of feeling of ecstasy there. That’s the best way I can explain why that music that I started out with speaks to us so much. There's a feeling you can get sometimes when you lean into that state—the Garden of Eden is actually in sight, there it is, around the bend. That can be very uplifting.

You wrote that Christ died on the cross, but we focus on his birth and resurrection. As part of our religious culture and Western culture, we have this radical focus on positivity. What might death itself offer us, and how could we be potentially impeding our own spirituality, or spiritual growth, by trying to avoid it?

We're living in a culture that’s in such a state of death denial on a daily basis. I don't even think we realize how extreme it is. People used to die at home, so life and death were just a natural part of everyday life, and we were constantly aware of death. Now death happens very discreetly, offstage in the hospital, and it only affects the immediate people around the dying person. And even for those immediate people, they're usually encouraged to get over it in some way.

One of the things that we lose is an intense sense of the preciousness of life on the one hand, and on the other hand, the fact that everything is probably going to be okay no matter what. There's a practice in many wisdom traditions: the stoics called it memento mori, which means to remember death. People were encouraged to actively, constantly remember that they might die at any moment. It was so extreme that if they had a military commander who had just been successful on the battlefield walking in full regalia through the amphitheater with everybody throwing flowers on him, he would be followed by loyal courtiers who would be saying, remember, you're going to die. Remember you're going to die.

So I started trying this practice myself, and it really was so transformative. When my kids were little, we had a bedtime ritual. It was definitely one of the best parts of the day. It was super cozy and intimate. But I was really busy professionally during that time of life, and I found myself during those bedtime routines sometimes having trouble not checking my cell phone for incoming emails. Even though I really didn't want to be doing that, I did. And then I started doing this memento mori practice, and I would say to myself, you know, you may not be here tomorrow, or your beloved son may not be here tomorrow.

That changed everything. I just put the phone down instantly. I had no desire to pick it up again; its pull over me was completely gone. And that's just one way in which having death be a more natural part of our lives casts those lives in a more beautiful shadow, kind of like the shadow of autumn. You know how in autumn, everything is super beautiful? The shadows are longer and more intense. That's what it's like to practice memento mori.

Can you talk about what else we lose when we sweep bitterness under the rug? When we push away anything that doesn't feel like positivity, what else are we losing?

Well, we're losing our mental health. My dear friend Susan David, an amazing psychologist, speaker, and writer who talks a lot about emotional resilience, was fourteen when her father died of cancer. Susan is a very cheerful, upbeat person by nature. And she knew that what everybody wanted from her was to be okay, even though she had just lost her father. So she's fourteen years old and she goes back to school and acts like a regular fourteen-year-old kid. And people ask her, are you okay? She was a master of being okay. But she really wasn't okay—she was going into the bathroom and throwing up her food after every meal. She developed bulimia. And she said this would have gone on indefinitely, but she had an English literature teacher who handed out blank notebooks to the kids in the class.

The teacher had also lost a parent at a young age, and the teacher looked Susan directly in the eyes and said, I want you to write down exactly what you really feel. Tell the truth about how you feel. And it's just for you—I'm going to read it, but this is your space to tell the truth.

And Susan describes that moment as a revolution in a notebook because it was the first time anybody had told her to really say how much pain she was in. And far from inviting her to dive into pain and never come out again, it was exactly the opposite. That was the core, where she first began to build the emotional resilience that she has.

You mention that artists do some of their very best work during these bittersweet moments of their lives. I could see how some people might be afraid that leaning into pain could make them feel worse, that they're going to get lost in despair. Can you talk about what you learned about creativity?

What I would say to someone feeling that way is to listen to Beethoven's Ode to Joy. It's one of the most transcendent pieces of music ever written, and it was written during the years that Beethoven was losing his hearing, which for a musician was the ultimate loss. It was a really terrible time for him, and look at what he did with that. You listen to Ode to Joy and it is literally an ode to joy. It was written in honor of this poem that he loved, a poem celebrating love and unity and enlightenment values. So it's music that is all about joy, and at the same time, you can't listen to it without hearing these great echoing waves of sorrow and longing. They're just part of the music and they're what infuses it with greatness.

The creative act that we might perform as an act of transformation of our pain will reflect our pain in some way, but it doesn't have to be only about that. It's much more complicated. If you're in pain, it's because you've lost something—but you haven't lost something unless you also loved it. So the best creativity is expressing the loss and the love simultaneously. They're flip sides of the same thing.

No one likes being in pain. I think we really only have two choices of what to do with it when it comes. Choice number one is taking it out on ourselves or on the people around us, whether it's through depression or aggression or whatever it is. And choice number two is ultimately finding a way to live with it and turn it in some direction of beauty or use or whatever it can be.

This interview was edited for length and clarity by Lori Forsyth and Allison Pond. To listen to the audio version of this interview, click here or listen below.