Local Hero

Businesses had closed for the weekend when nineteen-year-old Wayne Brockbank Hales lined up with forty-three other runners across Salt Lake City’s Main Street, a stone’s throw from the temple. It was the afternoon of Saturday, December 6, 1913, and the temperature hovered just above freezing. In a moment, a pistol shot would signal the start of Salt Lake’s first “modified marathon,” a five-mile foot race through the city. Aside from a few “unaffiliated” runners, each athlete hailed from schools or gymnasiums along the Wasatch Mountains. Wayne, a physics major in his sophomore year, represented Brigham Young University.

Somewhere, I have a photograph of Wayne cradling me in his arms. He’s eighty-six years old and has only a few months to live. I’m a newborn, his great-grandson, almost too small to see in the picture.

Our childhoods could hardly have been more different. Born in 1893 to a polygamous family, Wayne grew up in his mother’s home in Spanish Fork, Utah, while his father lived with his other wife in Eureka, a mining town more than thirty miles away. Wayne had fond memories of Spanish Fork, where he was constantly around family, including a grandmother who had experienced every stage of the Mormon westward migration.

But his life took a sharp turn after his mother’s death from pneumonia in 1906, which split the family further apart. While their older siblings fended for themselves, twelve-year-old Wayne and two of his sisters moved in with their father. Within a few years, Wayne was attending high school during the day and working in the mines at night.

I was born in Utah as well, but my family soon moved to Cleveland, Ohio. We then moved to the east side of Cincinnati, where my dad worked for a local tech company. Until she started nursing school in the early 1990s, my mom stayed at home and made sure that my four siblings and I had happy childhood memories. When I was six, my family moved into a good-sized house with a creek in the backyard and acres of woods up against the property.

I remember spending hours in the woods with my brother and our friends. Our backyard creek emptied into a larger creek that went on for miles in both directions, full of tadpoles, crawdads, and hard-to-catch minnows. As we got older and bolder, the creek became uncharted territory to explore. If we ventured west, we quickly came to a concrete overpass with the Dantean message “WELCOME TO HELL” scrawled across it in blue spray paint. This was our gateway to adventure.

I did not spend as much time in the woods as my brother did. Serious allergies gave me an excuse to stay inside, draw comics, and watch a lot of 1980s television. Large brown bookcases, flanking both sides of the wood-burning stove in our family room, also called to me. The right bookshelf had dozens of old books on American history, some paperback novels, and a set of children’s encyclopedias. The left bookshelf had church books, mostly by General Authorities from the 1970s.

If my childhood had anything in common with Wayne’s, it was reading. Working as an upper carman in Knightville, a boom town west of Eureka, he read books like Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur and Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables between emptying cartloads of ore and waste from the mines. I read and reread C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia and Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark before graduating to high school classics like Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms and John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

Wayne’s self-published autobiography, My Life Story, sat among my family’s church books. It was hardbound in dark imitation leather with gold lettering on the front cover and spine. Inside was a roughly chronological record of his life, full of folksy anecdotes and plenty of black-and-white photographs. These pictures drew me into the book. There were photographs of his tiny lap-sided home in Spanish Fork and his grade school friends, all standing together like extras from Little House on the Prairie. History was my favorite subject in school, so looking at Wayne’s photographs was like hopping into a time machine.

My Life Story was where I first learned about Wayne’s renown as a cross-country runner. He grew up at a time when reformers promoted athletics as a way to build character and keep young men away from alcohol, gambling, and other vices. In Eureka, Boy Scouts introduced Wayne to baseball, soccer, and other outdoor activities. He also played high school basketball and woke up early to run along a nearby railroad track. When Wayne enrolled at BYU in 1912, the chair of the school’s Athletic Council encouraged him to compete in an upcoming cross-country race in Provo. Wayne did and took first place—a feat he repeated the following year, just ten days before the modified marathon in Salt Lake City.

When it came to sports, I did not follow in my great-grandfather’s footsteps. My parents were not avid sports fans, and they never pushed me into basketball or soccer or any other kind of sport that kids play. One summer, collecting baseball cards led me to give Little League a try, and the experience remains a blot on my otherwise happy childhood. I’ve never liked having anything—large or small—hurled at my face, so standing in the batter’s box, staring down a seven-year-old pitcher with uncertain aim, redefined terror in my young mind. That season, I never once hit or caught the ball, and we lost every game.

I fared no better in other sports. From kindergarten to twelfth grade, gym class was an hour of humiliation. A group of girls in fourth-grade gym taunted me because I dove for cover when a volleyball came my way. A few years later, during a softball game, the other team saw that I couldn’t catch and made sure they hit every ball my way.

For a brief time, I thought about running high school cross country. I couldn’t throw a football or shoot a hoop to save a cat, but I had no trouble running a mile. I enjoyed circling the track, watching other kids slow down or drop out as I passed them. But by the time I reached high school, my confidence in sports—and in most other aspects of life—was shot. Thank goodness people liked my comics. Otherwise, high school would have been a lot worse than Little League.

When I look at pictures of my great-grandfather in his track uniform, I think about the first stanza of A. E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young”:

The time you won your town the race We chaired you through the market-place; Man and boy stood cheering by, And home we brought you shoulder-high.

Winning races at BYU made Wayne a local hero—someone man and boy could chair across campus amid the cheers of adoring fans. Long in limb and lean in muscle, he was handsome, well-spoken, devoutly religious, and incredibly smart. It’s no wonder that his BYU classmates voted him sophomore class president in 1913. When they sent him north that year to compete in the modified marathon, they had every reason to believe he’d dominate the course.

But his competition was stiff. Wayne’s BYU teammates, Bert Sumison and Eugene Stowell, who had placed just behind him at the cross-country run ten days earlier, were running the race. So too were Nathan Tolman and Orin Jackson, star runners at Logan’s Brigham Young College. Two last-minute entries, L. H. Wadsworth and W. B. Stoddard, were “distance runners of merit” from Hooper, Utah.

The race was supposed to start by a statue of Brigham Young at the intersection of Main Street and South Temple, but a crowd of spectators around the monument had pushed the runners back several yards, perpendicular to the old east wall of Temple Square. When the pistol fired, Herbert Williams, a California bookkeeper who had recently moved to Utah, burst from the starting line, tearing past the crowd as Wayne and the other runners scrambled to catch him. They shot south down Main Street, turning east for a block at 600 South before continuing the course down State Street.

Road races in 1913 were not the orderly events they are today. The organizers of the modified marathon had done their best to clear the streets, but as Wayne raced through the city, he had to dodge bicycles, leap over dogs, weave around pedestrians, and watch for reckless drivers. At 900 South, he and the other racers ran into a paving crew that forced them off the road, over an embankment, and onto a rutted, weedy path. From there they pressed on a few more blocks, their pace slowing, before finding their way back to Main Street. They then turned north for a two-and-a-half-mile dash back to where they started.

Wayne was in tenth place at the turn, where the course was even more chaotic. Cars and motorcycles clogged the street, choking the air with dust and exhaust. Motorists plowed through intersections, sometimes swinging wildly in front of the runners. Wayne wound his way through this maze until the traffic thinned and he had a clear shot to the finish line. But by then Herbert Williams had all but won the race. At 100 South, the crowd of spectators swallowed him whole and spit him out one block later at the finish line. Nathan Tolman, the star from Logan, came in second, finishing a minute and a half after Williams.

Still, Wayne powered on, passing runner after runner. Wadsworth and Stoddard, the “runners of merit” from Hooper, were at the back of the pack. Wayne’s teammates from BYU were closer—but not close enough to overtake him. At some point, Wayne passed Orin Jackson, the other runner from Logan, putting several yards between them. But as they approached 100 South, neither runner could see the finish line through the crowd. Unsure what to do, Wayne ran around the spectators, passing just left of the official finish line. Jackson, meanwhile, fought his way through the crowd, crossed the line, and immediately collapsed from exhaustion.

Although Wayne had technically not crossed the finish line, the referee awarded him fifth place and Jackson sixth. In an act of good sportsmanship, Jackson’s coach accepted the decision. The next day, Wayne’s name appeared in the newspapers alongside the other finishers. His official time went unrecorded.

I thought about Wayne as I lined up for the 2022 Salt Lake City Marathon. I was forty-two years old, more than twice his age when he’d run the modified marathon a century earlier. I was still afraid of the ball and had no interest in team sports. But in my late thirties, I had taken up running in defiance of middle age and my desk chair. Some men buy fancy cars when they experience a midlife crisis. I bought gym shorts for the first time ever.

The morning of the marathon was cold and drizzly. Before leaving for the race, I grabbed a rain jacket. It turned out to be a lifesaver. The marathon was a steady 26.2-mile slog through Utah’s wild April weather: rain, sleet, wind, snow, and very little sun. Without the jacket, my moisture-wicking gear would have soaked through—not ideal for a run that I wanted to be a tribute to my great-grandfather and his legacy.

When I picked up running, I was surprised when my heart turned toward Wayne’s. I remembered the grainy photographs of his glory days as a local running hero, and I wondered what might have happened if I’d had the confidence to be a runner in high school. Would I have been a local hero too? I never timed my mile back then. I’ll never know how fast I was—or could have been.

But speed has never interested me as much as distance. Maybe I like putting miles between me and the kids who bullied me in gym class. Maybe I like the feeling of leaving my footprints on a road, something people have done for generations. Or maybe I just like the flex of telling my kids on Saturday morning that I ran a dozen miles before they got out of bed.

One year after the modified marathon, Wayne won the cross-country race in Provo for the third year in a row, earning him a silver cup. But that was hardly his last or greatest accolade. He graduated from BYU in 1916 and later earned a Ph.D. at the California Institute of Technology. He was the first president of Snow College and later became a physics professor at BYU, his institutional home for the remainder of his professional life. When I attended BYU in the early 2000s, I had chemistry class in a lecture hall named for him.

As far as I know, Wayne never ran after college. He married Belle Wilson, the most popular girl in his graduating class, and they had six children together. I heard my uncle once describe him as the “founder of the family,” a nod to the value he placed on keeping his posterity together. His parents’ family had fractured first under polygamy and then with his mother’s death, so it’s not surprising that he held regular family reunions with his children and grandchildren. In my house, I have a letter he wrote to me on the day I was born, a testament to the care he put into turning his own heart to the next generation.

The Salt Lake City Marathon begins at the Olympic Legacy Bridge at the University of Utah and follows a northwest course through the Federal Heights neighborhood, where my father lived as a boy. As I ran past the meetinghouse where his family attended church, I thought about the imprint of time and history on land and families. The weight of a century hit me like a hard rain. It was heavy, but not like a burden. It felt instead like a chain linking my heart to each heart that preceded it: my father’s, my grandfather’s, and Wayne’s.

I could see him, my great-grandfather, dressed in shorts and a light sweater, dodging cars as he dashed down Main Street.

We ran the next few miles together.

Scott Hales lives in Utah. He is the author of “The Garden of Enid: Adventures of a Weird Mormon Girl” (2016, 2017) and “Hemingway in Paradise and Other Mormon Poems” (2022). He likes to make art, visit old cemeteries, and run long distances.

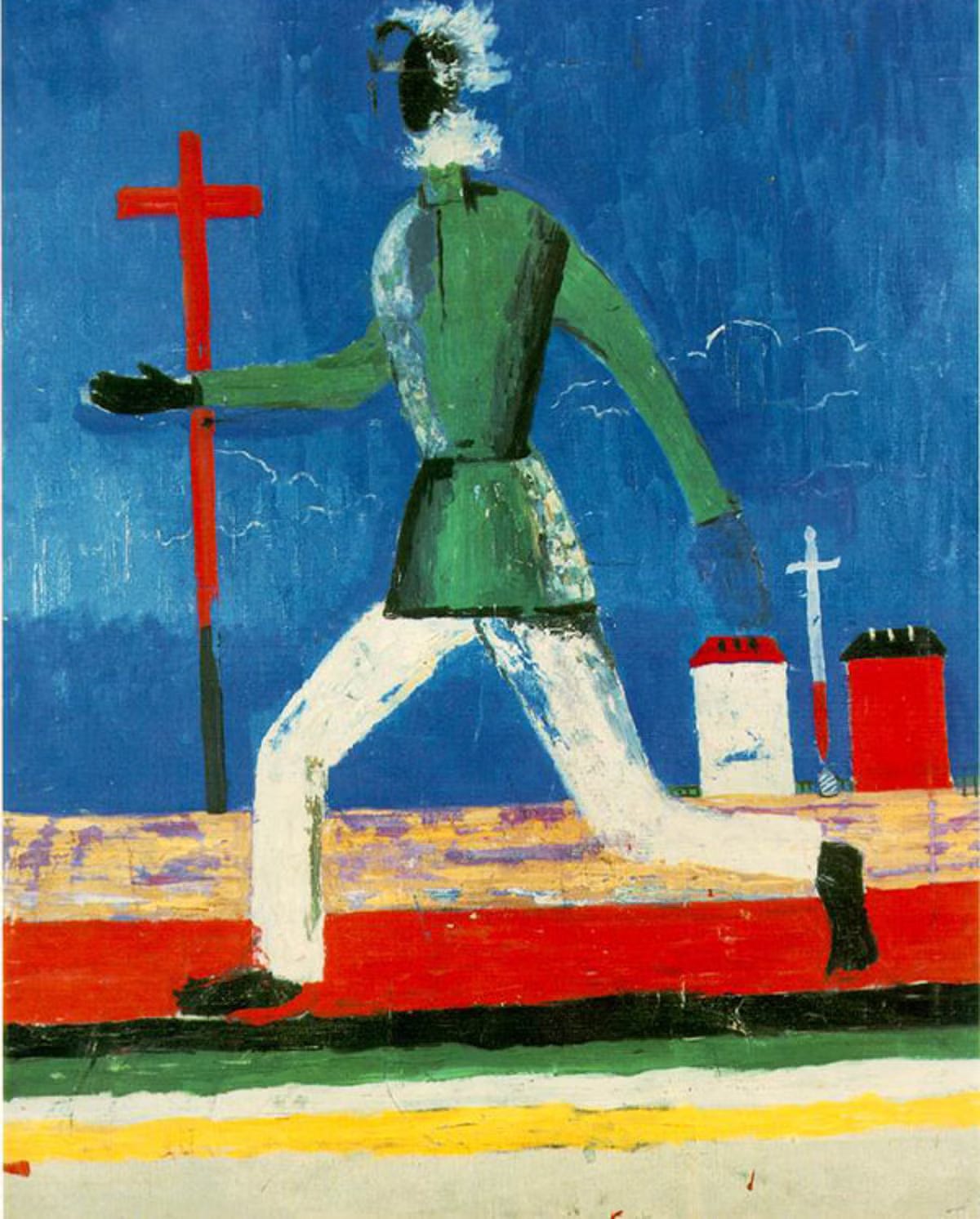

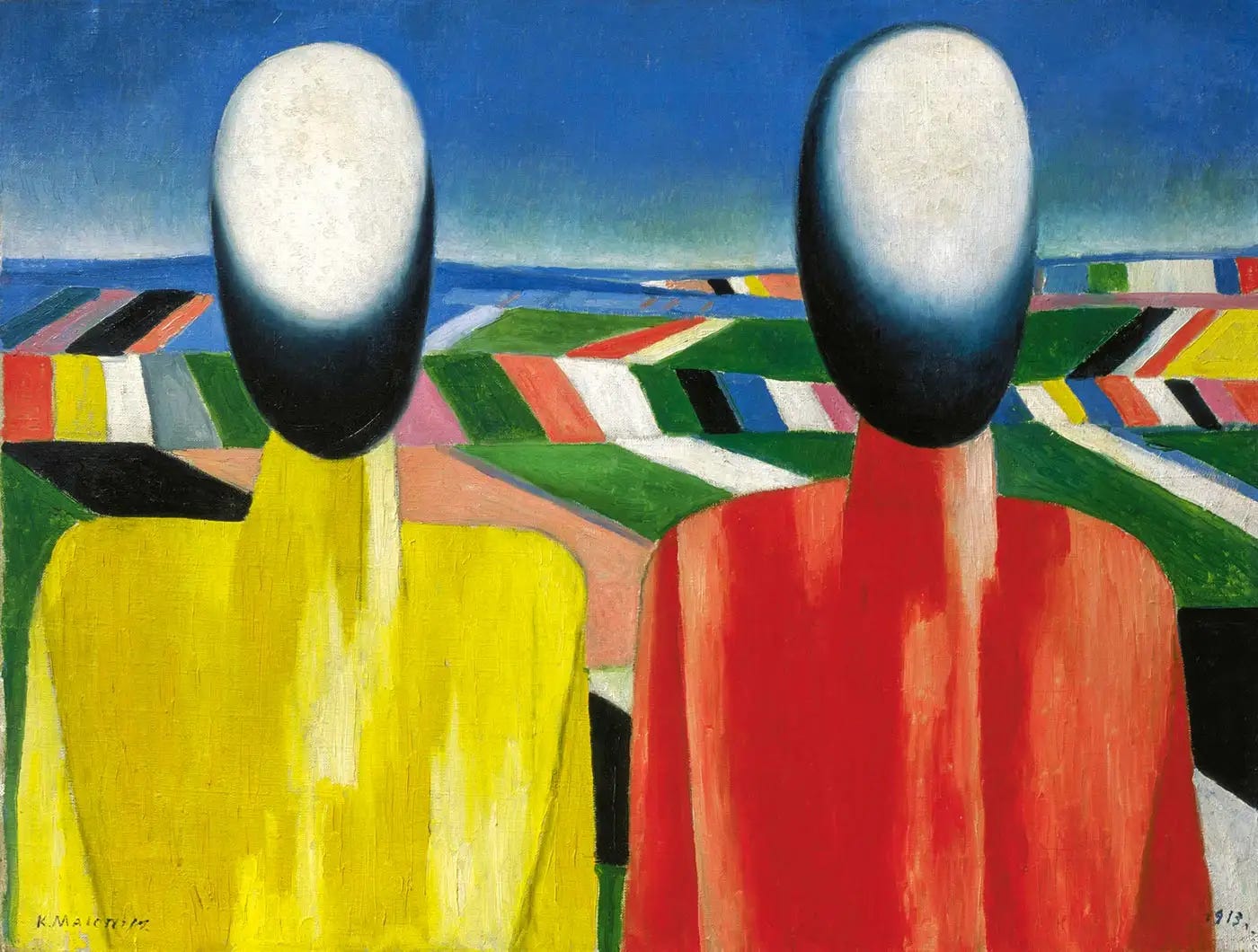

Art by Kazimir Malevich.

I was fascinated by your story of Grandpa Wayne, as I knew him. He married my grandmother, Vivian, after their respective spouses passed away. I have fond memories of him but knew nothing about his athleticism as a young man nor of the hardships he experienced as a boy. Thank you for opening another window into the life of a man for whom I had enormous respect and love.